OPINION: Since its inception Zimbabwe has been a divided country. Yet after the recent elections there may be hope, provided a ‘healthy’ opposition can rise to the occasion.

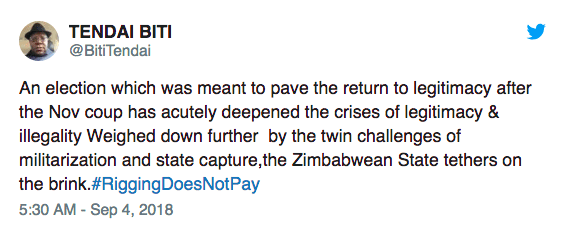

President Emmerson Dambudzo Mnangagwa (“ED”) recently penned an op-ed in The Guardian titled, “As president, here’s what I want for Zimbabwe: a healthy opposition.” Mnangagwa wrote, “Indeed, the role of opposition leader is critical to democracy’s function. The incoming administration will be weaker if not held to the checks and balances that parliament provides. Were he to renege on this role, it will only sap the nascent democratic culture taking root.”

The victory of ED and the Zimbabwe African National Union – Patriotic Front (ZANU-PF) in the recent Zimbabwe elections over the cobbled-together forces of some of the opposition parties was not a surprise. It was a “harmonised election” in that it combined a vote for a president, a parliamentary seat and officers in local governments on the ballots.

Of the 133 registered political parties in Zimbabwe, 55 fielded 23 candidates for president in the July 30th election. Four of the candidates were women: Joice Mujuru (the People’s Rainbow Coalition); Thokozani Khuphe (MDC-T); Melbah Dzapasi (#1980 Freedom Movement Zimbabwe); and Violet Mariyacha (United Democratic Movement). 210 seats were contested for the House of Assembly by various political parties and independent candidates. The Electoral Commission announced that the final tally of registered voters was 5.6-million.

The principal opposition which sought to oust the ruling ZANU-PF was the MDC Alliance, a coalition made up of seven political parties. These were the MDC-T (Nelson Chamisa)‚ the MDC (Welshman Ncube)‚ the People’s Democratic Party (Tendai Biti)‚ Transform Zimbabwe (Jacob Ngarivhume)‚ Zimbabwe People First (Agrippa Mutambara)‚ Zanu-Ndonga (Denford Musayarira), and Multi-Racial Democratic Christian Party (Mathias Guchutu). As most of these members of the Alliance have spent the last eight years tearing pieces off each other in an extensive battle of factions for the remnants of the original Movement for Democratic Change, led by opposition leader Morgan Tsvangirai, their unity was tissue-thin.

The fact that these seven factions joined together to fight the election did not resolve the fundamental problem that the MDC has faced over the years. In its 20 years of existence, the MDC hasn’t come up with a viable plan for taking power from an entrenched ZANU-PF under Robert Mugabe and later Emmerson Mnangagwa, who were prepared to use force to render the MDC powerless. Voters are all too familiar with a pre-election routine in which MDC leaders prophecy imminent change—and bay at the moon impotently following their loss of another election.

The wrong that happened last November has been erased by his victory in the July 30 elections. We now have a government born out of the constitution. I now accept [Emmerson Mnangagwa’s] leadership and he now deserves the support of every Zimbabwean.

-Robert Mugabe, September 6, 2018

In the 2008 presidential election, where Morgan Tsvangirai (MDC) challenged Robert Mugabe (ZANU-PF), the MDC refused to participate in a second round even though it had a slight lead over ZANU-PF in the first round. In Parliamentary elections, the MDC won control of the legislature, and Tsvangirai would become prime minister. However, the incompetence of the MDC in power led to wide disillusion by the electorate. The MDC showed itself and its leadership to be grossly incompetent in performing its governmental duties. The apathy of the Zimbabwean electorate towards the MDC as a result has been a major factor in failing to create a party with mass appeal.

In 2008, the first acts in government by Tsvangirai and Tendai Biti (then in charge of the economy as Minister of Finance) frightened everyone, including the MDC overseas sponsors. Tsvangirai and Biti announced, to the horror of the security chiefs in the Army and the Police, that the MDC would give back the farms which had been taken from their owners by ZANU-PF. Irrespective of the merits and morality of such an action, a precipitate dislodging of the current occupiers would have presented the authorities with a security nightmare they knew they couldn’t control. It was a recipe for conflict which no one could control. The security forces were alarmed.

Even worse, when the issue of transition to a possible new MDC government arose at a 2008 emergency meeting of the Southern African Development Community (SADC) after the election, MDC leadership alleged there were British Special Forces standing by at a “secret airbase” in Botswana run by the Americans who would come in, arrest the Zimbabwe security chiefs, and take over internal security until order was re-established.

A pattern of behaviour by Biti and his supporters that was established in the 2008 election would be repeated again in the 2018 election.

In the 2008 campaign, a rash of emails and SMS messages emerged full of disinformation such as that Tsvangirai had been killed, and that his bodyguards had been massacred and electoral fraud was widespread. The source of these messages was found to have come from within the US Embassy in Harare. These false messages also announced fake press conferences, false electoral results and fake meetings. On further investigation it was found that two US nationals employed by the National Democratic Institute, an NGO sponsored by USAID, were the source. They were deported at the request of the Zimbabwean government.

At the same time Zimbabwe authorities observed clandestine meetings between MDC officials and some members of the Zimbabwe Electoral Commission (ZEC). The MDC were offering incentives for the ZEC to come up with a low count for Mugabe’s votes. These were taped, and the perpetrators arrested. Seven ZEC people were arrested and accused of deliberating low-counting Mugabe votes in four provinces. The MDC went to the High Court for a Writ of Mandamus, charging the ZEC with the urgency of releasing its figures on the Presidential ballot, even though all the ballots had not been fully verified.

There was a nasty backlash from all the above elements. The MDC propaganda was full of Biti’s fantasies, but the rank and file know that most of what had been said was an exaggeration. At the same time the ZANU-PF people felt a sense of outrage at the attempt by the MDC to steal the election and to portray the country internationally as filled with thugs, bandits and plotters.

Biti and MDC-T presidential candidate Nelson Chamisa repeated these very same lies and exaggerations during the recent 2018 election. They pushed to get bodies in the street to protest and demonstrate. The Army responded with excessive violence and made the MDC case easier to credit.

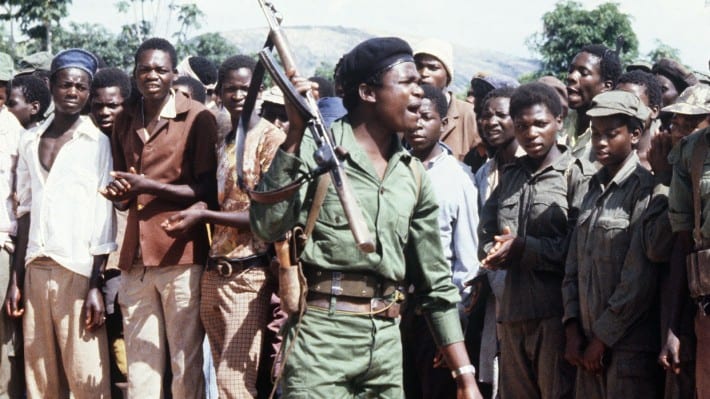

The MDC embarked on a campaign of manipulation issuing false and misleading statements. MDC Secretary-General Biti made wild claims of a 60% sweep of the election, unbelievable even to others in the MDC. His tales of ballot-rigging and violence against voters had no basis in fact. Biti and Chamisa attempted to create an image, primarily designed for the international audience, that somehow the ZANU-PF were rigging the election and the MDC was their innocent victim.

Biti would seek asylum in neighbouring Zambia but was deported back to Zimbabwe in a move condemned by the United States. He was also charged with falsely and unlawfully announcing results of the July 30 election, which Chamisa also rejected as fraudulent. Their challenge to the election in the Constitutional Court was rejected weeks later. If found guilty, Biti could face up to 10 years in jail, a cash fine or both.

As this election was part of an attempt by ED and ZANU-PF to throw off the perceived mantle of misrule by Mugabe and the “Lacoste” and “G40” factionalism within ZANU-PF, these events have made it more difficult to set off on a new path of legitimacy, rule of law, and economic renaissance which Zimbabwe urgently needs.

Zimbabwe’s Political Past

Zimbabwe has an unusual political history. The country was invaded by white British mining entrepreneurs in 1889, led by Cecil Rhodes, who set up the British South Africa Company (‘BSAC’) to exploit the gold mining wealth of Mashonaland. It was granted a Royal Charter in 1889 modeled on that of the British East India Company. As in the Indian subcontinent model, the BSAC became the ruler of the lands in South Africa, Rhodesia, Botswana and Zambia. The BSAC maintained its own mercenary army and enforced its version of the law in the territories it controlled. Its principal source of wealth and power derived from its mining interests in South Africa.

The BSAC control of its South African business was threatened by the Great Trek of Afrikaaners from the Cape to their new homes in the Transvaal and the Orange Free State when 12,000 to 14,000 Boers from Cape Colony in South Africa, between 1835 and the early 1840s, rebelled against the imposition of British rule and searched for fresh pasturelands beyond the reach of the Cape Colony. There was another ‘Voortrekker’ colony established in Natal, but the British took it over, yet granted recognition to the Transvaal and Orange Free State in 1854.

Rhodes had many supporters in London and plotted with them to create a false “civic uprising” in Johannesburg which could be used to oust the Boers in the Transvaal. Rhodes formed the “Reform Movement” to fight against the new taxes and administration by South African Republic President Paul Kruger over the Johannesburg mining interests. The Reform Movement decided to overthrow the Transvaal government by taking up arms. The uprising was timed to coincide with an invasion of the Transvaal from Bechuanaland (present day Botswana), by Dr. Leander Starr Jameson, who commanded the BSAC mercenary army. Rhodes wanted to take over the government of the Transvaal and turn it into a British colony that would join all the other colonies in a federation. Chamberlain helped plan the Jameson Raid.

The raid was launched on 29 December 1895 but was a failure as none in the Reform Movement could agree on a common plan. Jameson was forced to surrender to the Boers on 2 January 1896 at Doornkop near Krugersdorp. Many were put on trial and the British removed Cecil Rhodes from his post as the premier of the Cape Colony. This defeat of the BSAC forces spurred on the leaders of the African communities in Rhodesia to rise up to drive the company out of its lands. They began a war against the occupying forces. They called this a Chimurenga, a word in the Shona language, roughly meaning “revolutionary struggle”. This First Chimurenga refers to the Ndebele and Shona insurrections against the BSAC during 1896-1897, also called the Second Matabele War.

The ill-fated Jameson Raid left the company’s Rhodesian forces depleted. The Ndebele began their revolt in March 1896. In June 1896, Mashayamombe led the uprising of the Zezuru Shona people located to the South West of the capital Salisbury. The third phase of the First Chimurenga was joined by the Hwata Dynasty of Mazoe. They succeeded in driving away the British settlers from their lands on 20 June 1896. However, by 1897 the BSAC’s forces, the British South African Police, were able to regain their lost territories. The First Chimurenga ended on October 1897. Matabeleland and Mashonaland were unified under company rule and named Southern Rhodesia, still under the control of the BSAC.

The Rhodesians sent troops and men to fight for the British during the Anglo-Boer War (1899-1902). They were under the general command of Colonel R S S Baden-Powell of the 5th Dragoon Guards (the founder of the Boy Scouts). They restored the BSAC in the Rhodesias. The issue of land tenure was crucial to the development of the region. The Land Tenure Commission reserved all the lands, other than enclosed in “Native Reserves” to the whites. The Committee’s land apportionment was 19 million acres of prime farmland for Europeans and 21.4 million acres for Native Reserves. A further 51.6 million acres was unassigned, but available for future alienation to Europeans.

![Image Battle of Majuba Hill on 27th February 1881 in the First Boer War. [Picture by Richard Caton Woodville]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/Boer-War.jpg)

Ethnic and Political Divisions in Zimbabwe

and the Struggle Between the Karangas and the Zezurus

Zimbabwe has been since its inception a divided country. The first division is the great tribal split in Zimbabwe between the Shonas and the Ndebele – the latter an offshoot of the Zulus of South Africa who moved into Matabeleland under the leadership of Mzilikazi, one of Shaka’s lieutenants. Most of post-independence Zimbabwean politics has been the jockeying for power between the distinct clans that make up the Shona.

The Shona, who began arriving from west central Africa more than a thousand years ago, share a mutually intelligible language. But ethnically they are not homogenous. Between the clans there is a diversity of dialects, religious beliefs and customs.

The five principal clans of the Shona are the Karanga, Zezuru, Manyika, Ndau and Korekore. Of these, the biggest and most powerful clans are the Karanga and the Zezuru. From the beginning an almighty struggle has been going on within ZANU-PF between Karangas and Zezurus.

The Karanga are the largest clan, accounting for some 35 per cent of Zimbabwe’s 11.5 million citizens. The Zezuru are the second biggest and comprise around a quarter of the total population. The Karanga provided the bulk of the fighting forces and military leaders who fought the successful 1972-80 Second Chimurenga (struggle) that secured independence and black majority rule. Nevertheless, the ZANU movement – since renamed ZANU PF – was led by a Zezuru intellectual with several degrees – Robert Mugabe.

The Zezuru hegemony has crept up and became a fact of life in Zimbabwean politics, although for many years there was intense debate as to the authenticity of Mugabe’s origins.

What is more certain is that in 1963, when ZANU was formed, Mugabe was appointed to the powerful position of secretary general after being nominated by the late Nolan Makombe, a leading Karanga who had convinced his co-tribesmen in the movement that Mugabe was a fellow Karanga of the influential Mugabe dynasty of chiefs from the area of the Great Zimbabwe ruins near Masvingo. Mugabe cleverly encouraged this belief until he was well entrenched in power.

Although at its inception ZANU was led by Sithole, a Ndau from Manicaland from the far east of Zimbabwe, the party was dominated by the Karangas. Its powerful individuals included Leopold Takawira, Nelson and Michael Mawema, Simon Muzenda and Eddison Zvobgo – all Karangas. The tribal composition replicated itself in the armed wing of ZANU with the Karangas, led by Josiah Tongogara, forming the backbone of the liberation struggle. Other prominent Karangas were Emmerson Mnangagwa, retired Air Marshal Josiah Tungamirai, and Army Commander Vitalis Zvinavashe.

When in 1974 Mugabe was smuggled out of what was then Rhodesia into Mozambique by a Manyika chief, Rekayi Tangwena, to join the Chimurenga, he was not easily accepted by the Karanga and Manyika guerrilla leadership. When he eventually ascended to power, the first thing he did was to neutralise the Karanga element in the movement by imprisoning many of them – most notably Rugare Gumbo who was the original mastermind of the guerrilla war. Gumbo and several fellow Karanga leaders were kept in underground pit dungeons until independence in 1980.

During the 1972-80 Second Chimurenga (the war of independence) there were two separate parties and two separate armies. The main liberation party, the Zimbabwe African People’s Union (ZAPU), had split into two groups in 1963, with the split-away group being named Zimbabwe African National Union (ZANU). Though these groups had a common origin they gradually grew apart, with ZANU recruiting mainly from the Shona regions, and ZAPU recruiting mainly from Ndebele-speaking regions in the west.

The armies of these two groups, ZAPU’s Zimbabwe People’s Revolutionary Army (ZIPRA), and ZANU’s Zimbabwe African National Liberation Army (ZANLA), developed rivalries for the support of the people and would also fight each other. When Zimbabwe won independence, the two armies so distrusted each other that it was difficult to integrate them both into the National Army. These problems were not only in Matabeleland, but throughout the country. For example, former ZANLA elements attacked civilian areas in Mutoko, Mount Darwin and Gutu.

There were major outbreaks of violence between ZIPRA and ZANLA awaiting integration into the National Army. The first of these was in November 1980, followed by a more serious incident in early 1981. This led to the defection of many ZIPRA members. It was thought that ZAPU was supporting a new dissident war to improve its position in Zimbabwe. In the elections held in April 1980, ZANU-PF received 57 out of 100 seats and Robert Mugabe became prime minister.

With the election of Mugabe in 1980 the government was directed to putting Zezurus and their allies the Korekore in most of the positions of power in the new state. Mugabe is a Zezuru, the head of the Zimbabwe Defence Forces, General Constantine Chiwenga (formerly Dominic Chinenge), is a Zezuru, and almost half the top commanders with the rank of Colonel in the Zimbabwe Defence Forces are Zezurus.

Until recently the head of the Central Intelligence Organisation, Major-General Happyton Bonyongwe, was Zezuru and almost half of the intelligence officers with the rank of Provincial Intelligence Officer are Zezurus. The head of the Zimbabwe Republic Police until recently was Commissioner-General Augustine Chihuri (a Zezuru) and half of the police commanders with the rank of Assistant Commissioner are Zezurus.

The head of The Air Force of Zimbabwe, Air Marshal Perence Shiri, is the first cousin of President Robert Mugabe. Half of the commanders with the rank of Group Captain are Zezurus. The head of the Prisons of Zimbabwe, Major-General Paradzai Zimonde, is Zezuru and nearly half of the commanders with the rank of Colonel are Zezuru. The Chief Justice of Zimbabwe is Godfrey Chidyausiku who is a Zezuru and the Judge President George Chiweshe is a Zezuru and half of the judges are Zezuru / Korekore. Nearly half of the cabinet of Zimbabwe since 1980 has been composed of Zezuru/ Korekore and half of Permanent Secretaries are Zezuru and Korekore.

To quell any Karanga suspicions of his tribal manoeuvres, Mugabe kept the respected Simon Muzenda, a Karanga, as his sole vice president until the latter’s death in 2003. Other Karangas, such as the late firebrand lawyer Eddison Zvobgo, long seen as a future leader of the country, were systematically downgraded to provincial leaders. Josiah Tongogara, the military commander of ZANU in exile, was a Karanga who died in Mozambique on the eve of independence in an as yet unexplained car accident. Sheba Gava, a Karanga, was the most powerful woman guerrilla during the Seventies war but when she died in the following decade she was not granted national heroine status.

![Image [2008 Zimbabwe map][The Economist]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/Zimbabwe-map-2008.png)

For example, Mnangagwa is a Madyira, and Madyira and Gumbo people are all Mnangagwa’s relatives. In fact, in terms of classical Shona culture, even before you propose to a woman, you are supposed to ask for their totem. “Nhai asikana mutupo wenyu chii?” (Young lady, what is your totem?). That question is considered a traditional introduction of the intention to propose love in Shona culture and to avoid “incest” in marrying “your sister”.

What is more noteworthy in assessing affinities of the politicians is their clan, such as Mugabe’s identification with the Gushungo totem of the Zezuru. Former First Lady Grace Mugabe (although born in Benoni, South Africa) is a Sinyoro like many prominent Zimbabwean political figures. Joice Mujuro, former Vice President (though born in Mt. Darwin), is of the Korekore. These are distinctions that tend to matter even more than to which dialect group the politician belongs.

The discussion of ethnicity is not just a cultural construct. It has to do with the most important aspect of life in Zimbabwe, and indeed most of Africa – control and title to land. The question of belonging is not a theoretical exercise. There are rarely any certificates of title or Land Registries for non-white landholdings. The local ethnic group is the attestation and court of reckoning for land title. Outside of the cities, much of the only real title to land and water rights resides in the local community. The question of ethnicity is crucial to economic well-being and status. Projected onto the wider canvas of the political system the question of ethnicity is very important.

The Pernicious Policies of Britain and the U.S. in Zimbabwe’s Development

Although it is a simple shorthand to say that the ZIPRA forces were supported by the Soviet Union and the Eastern Bloc, and the ZANLA forces by China and North Korea, the overweening effect of the Cold War has had a devastating effect on Zimbabwe’s development.

Because of the support by independent Zimbabwe of the struggle against apartheid in South Africa, the battle to free Mozambique and Angola from the Portuguese, and, most especially, the military support offered to Joseph Kabila in his efforts to create a free and independent Democratic Republic of the Congo, the forces of the West lined up to oppose Mugabe. Added to this, the British policy of refusing to realistically oppose the UDI of the Rhodesian Front as “kith and kin” allowed this rebel group to wage a dirty war against the Zimbabwean liberation movements.

British rule over Zimbabwe ended in 1965 with the Unilateral Declaration of Independence by Ian Smith’s Rhodesian Front. Other than the few months at the end of the Rhodesian War when Abel Muzorewa’s Government reverted to British colonial control to negotiate the Peace Accords establishing Zimbabwe in 1979, Britain’s control over Rhodesia/Zimbabwe effectively ended in 1965.

There is, in reality, no one in Zimbabwe under the age of fifty who ever lived under British colonial rule. In fact, the median age in Zimbabwe is less than twenty years. That means that the largest sector of people in Zimbabwe not only never lived under British rule, they also didn’t live under Rhodesian Front rule either. Independence was almost forty years ago, and the bulk of Zimbabweans were not even alive at the time. Theirs is not the politics of colonialism or anti-colonialism; it is the politics of a nation beset by a concerted campaign by the international community against it.

The British Renege on Constitutional Promises

During the post-independence period, most of the “kith and kin” that the British saw as a group whose rights they had to defend, left the country. One would be hard-pressed to find more than a few thousand kith and kin left in Zimbabwe.

The British had bought some time for them by insisting at the Lancaster House talks that the new constitution include several “entrenched clauses” in the Zimbabwe Constitution, which protected the land rights and tenure of the white farmers for ten years after independence. The new Zimbabwean government agreed to suspend any expropriation of white farmers’ lands for ten years on the basis that the British give a solemn guarantee that, at the end of the ten years, Britain would make available one billion pounds to compensate the assist financially with the cost of transition from white-ruled farms to local land ownership. Yet, at the end of the ten years, the British refused to pay.

When Mugabe moved forward with land redistribution, he was told by British PM Tony Blair and the Labour Party that they would not compensate the land reform agreements because they had no faith in his government. Human rights abuses and the lack of democracy were cited as the reason. At the root of their argument, the Blair Government stated that it was the Conservatives who entered into the agreement for a new Zimbabwe, not Labour.

On November 5th, 1997 Clare Short wrote to Kumbirai Kangai, the Minister of Agriculture and Land, in which she said, “I should make it clear that we do not accept that Britain has a special responsibility to meet the costs of land purchase in Zimbabwe. We are a new Government from diverse backgrounds without links to former colonial interests. My own origins are Irish and as you know we were colonised not colonisers. We do, however, recognise the very real issues you face over land reform. We believe that land reform could be an important component of a Zimbabwean programme designed to eliminate poverty. We would be prepared to support a programme of land reform that was part of a poverty eradication strategy but not on any other basis.”

Mugabe went ahead with the land reform and claimed back the lands held by the white farmers, telling farmers to collect their compensation from the British Government. The conflict this engendered led to the seizure of white farms and the expropriation of some of their lands. The British, whose refusal to conduct its policy towards Zimbabwe according to its obligations, used these seizures as evidence of the supposed failure of ZANU to act fairly.

Again, I am told there were discussions in 1989 and 1996 to explore the possibility of further assistance. However that is all in the past. If we look to the present, a number of specific issues are unresolved, including the way in which land would be acquired and compensation paid – clearly it would not help the poor of Zimbabwe if it was done in a way which undermined investor confidence.

-Clare Short, November 5th, 1997 letter to Kumbirai Kangai

British Seek Vengeance Through Sanctions

In response, the British undertook a policy of almost two decades of political and economic subversion against the Zimbabwe government and encouraged its international partners in Europe and North America to follow its lead in combatting Mugabe and sanctioning the country and its political leadership. It created the MDC political party and promoted its leaders in Parliament, the European Union and NATO in their efforts to oust Mugabe and the ZANU-PF.

The efforts of the MDC to take power in the elections precipitated a period of violence and mayhem, which led to the doomed coalition of Mugabe, Tsvangirai and Mutambara. The coalition was doomed because it was accompanied by a unique and epic failure of the Zimbabwe dollar to retain its value. Spiraling inflation finally drove the country to abandon the Zimbabwe dollar (which had traded at one Zimbabwe dollar equaling one US dollar and sixty cents at independence). The US dollar and sterling were accepted as the currencies for Zim.

This destruction of the currency and the impact of the international sanctions imposed by Britain, the European Union and the United States had a devastating effect on the Zimbabwe economy and political structures. It has taken over ten years to start recovering from that crisis. The Zimbabwe economy has almost recovered from that crisis despite the sanctions and the imposition of foreign currencies as the reserve currency.

The U.S. Supports its British Cousins in Destabilising the Region

The role of the United States in undermining Zimbabwe and its economy was no better than the British. The US has always viewed the African nationalists of Southern Africa as its enemy based on the relentless Cold War policies of combatting the Soviet Union in every theatre. The nationalists of the ANC and PAC in South Africa, ZANU and ZAPU in Rhodesia, MPLA in Angola, FRELIMO and COREMO in Mozambique, and the several governments of the Democratic Republic of the Congo (starting with Lumumba) were all viewed as “too close to the Soviet Union” and thus the enemies of the US.

America has been fighting wars in Africa since the 1950s – in Angola, the DRC, Somalia, the Sudan, Ethiopia, Somalia, Morocco, Libya, and Djibouti among others. In some countries US troops were used, but in most cases the US financed, armed and supervised the support of indigenous forces.

In its support of the anti-MPLA forces in Angola, the US sent arms and equipment to the UNITA opposition. In the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Larry Devlin of the CIA was an unofficial branch of Mobutu’s government. The US ran its own air force at WIGMO. US airmen supported the South African forces in the Caprivi from WIGMO. The hostility and opposition of the US to African nationalism took many forms.

The US cast its first veto in the United Nations Security Council in 1970 when Ambassador Charles Yost vetoed a resolution on interdicting the international sale of Rhodesian chromite ore. The US argued that the beneficiary of the sanction against Ian Smith’s Rhodesia would be the Soviet Union, which was also selling chromite ore.

It has been a unique feature of US African diplomacy that the Cold War legacy of opposition to African nationalism continues to shape US policy. The US sanctions against Zimbabwe were established by the Zimbabwe Democracy and Economic Recovery Act of 2001 (ZDERA) and continue to today. The US has threatened to continue these sanctions and expand them because of its “uncertainty” about the election of Mnangagwa and ZANU-PF.

One of the Dirtiest of Dirty Wars

The Horrors of the Rhodesian Bush War

The predominance of youth in the Zimbabwean body politic has meant that they cannot remember, or never learned, some of the full horrors of the Rhodesian Bush War that preceded independence. For many of today’s aging political and military leaders and war veterans this is still a potent memory. It is one that shapes the conviction that foreign powers are still trying to manipulate the nation, and that the MDC and its factions are the main vehicles for that continued intervention. A lot of the sworn testimony that emerged from the 1996 Truth and Reconciliation hearings in South Africa after the end of apartheid produced testimony that would have created jobs for life if the International Criminal Court had existed then.

Even as they knew they were losing the battle in 1978, the Rhodies experimented with the use of weaponised anthrax against the civil population.

In 1979, the largest recorded outbreak of anthrax occurred in Rhodesia. As shown in sworn testimony and repeated in the autobiography of Ken Flower, Chief of Rhodesia’s Central Intelligence Organization (‘CIO’) and CIO Officer, Henrik Ellert, the anthrax outbreak in 1978-80 was anything but benign.

The original outbreak was the result of a policy carried out by the Rhodesian Front government with the active participation of South Africa’s ‘Dr. Death’ (Dr. Wouter Basson). Together with the South Africans, the Rhodesian Front used biological and chemical weapons against the guerrillas, rural blacks to prevent their support of the guerrillas, and even against cattle to reduce rural food stocks. Much of the detailed background of this program emerged from testimony at the Truth and Reconciliation hearings.

Testimony asserted that “Dr. Death” had used Rhodesia as a testing ground for their joint chemical and biological warfare programs. Witnesses at the commission testified to a catalogue of killing methods ranging from the grotesque to the horrific:

– “Project Coast” sought to create “smart” poisons which would only affect black people, and hoarded enough cholera and anthrax to start epidemics [UNIDIR / CCR Report: “Apartheid’s Chemical and Biological Warfare Programme”];

– Naked black men were tied to trees, smeared with a poisonous gel and left overnight to see if they would die. When the experiments failed, they were put to death with injections of muscle relaxants;

– Weapon ideas included sugar laced with salmonella, cigarettes with anthrax, chocolates with botulism and whisky with herbicide;

– Clothes left out to dry were sprayed with cholera germs;

– Water holes were doused with poisons to kill the cattle and anyone else who drank from them.

Dr. Basson was aided by the work of Dr. Robert Symington, professor of Anatomy at the University of Rhodesia. The active work was performed by Inspector Dave Anderton, head of the “Terrorist” desk at the CIO.

In 1979-80 there were 10,748 documented cases of anthrax in Rhodesia which involved 182 deaths (all Africans). In contrast, during the previous twenty-nine years there had been only 334 cases with few deaths. This was no accidental outbreak. Some of the weaponised anthrax was delivered to the US by the South Africans where it provided feedstock for the US chemical and biological storage trove.

Pfini Yenyoka Kungoruma Icho Isingadyi

There is an old Shona saying, “Pfini Yenyoka Kungoruma Icho Isingadyi,” which means “the spite of the snake is just to bite what he cannot eat.” Or, in other words, it is wrong to inflict unnecessary pain and anguish in an election which you cannot win.

![IMage A soldier stands guard during the inauguration ceremony of Emmerson Mnangagwa, at the National Sports Stadium in Harare. [Photo: Tsvangirayi Mukwazhi / AP]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/Zimabawe.jpg)

There is no question that the Army used excessive force in blocking misguided protestors pursuing their chimerical outcome. It is also true that ED is not everyone’s shining image of a democrat; his past is too well known and discussed. However, the election was much more than a beauty contest for ZANU-PF and ED. It was hoped that it would be a positive step in moving away from the legacy of the past and attracting capital investments, a stable currency and hope for the country.

Zimbabwe was one of the richest countries in Africa, abounding with enough foodstuffs to feed the whole African continent. Yet years of domestic bad planning coupled with a concerted program of destruction and interference by Britain and the West in the Zim finance and banking sectors devastated it.

There are no white knights in charge of the country. But there is a period of hope and expectation which might lead to real development and the spread of social justice, that MDC is trying to destroy. It should not be denied or impeded.

Except for the Army, the Karangas are finally in charge and are unlikely to be pushed out soon. The main worry is that the Karangas have not developed a younger cadre of potential leaders, as most of the oxygen of growth has been hoarded by the Zezurus. This will change if given a chance.

It would be a real pity if the “nay-sayers” are received as genuine victims. They are what they always have been – a foreign-sponsored band of incompetents whose skills include the dissemination of semi-plausible lies and the creation of dangerous distractions.

Zimbabwe deserves better.

Dr. Gary K. Busch, for Lima Charlie News

[Edited by Anthony A. LoPresti]

Dr. Busch has had a varied career-as an international trades unionist, an academic, a businessman and a political intelligence consultant. He was a professor and Head of Department at the University of Hawaii and has been a visiting professor at several universities. He was the head of research in international affairs for a major U.S. trade union and Assistant General Secretary of an international union federation. His articles have appeared in the Economist Intelligence Unit, Wall Street Journal, WPROST, Pravda and several other news journals. He is the editor and publisher of the web-based news journal of international relations www.ocnus.net.

Lima Charlie provides global news, featuring insight & analysis by military veterans and service members Worldwide.

For up-to-date news, please follow us on twitter at @LimaCharlieNews

In case you missed it:

![Image Zimbabwe’s Election - Is there a path ahead? [Lima Charlie News]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/Zimbabwe’s-Election-Is-there-a-path-ahead-Lima-Charlie-News.png)

![[Silver lining for China in Zimbabwe’s violent elections][Lima Charlie News]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/Screen-Shot-2018-08-02-at-12.51.35-PM-480x384.png)

![Image This Week in Business Intelligence [Lima Charlie News]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/This-Week-in-Business-Intelligence-Lima-Charlie-Business-Intel-Report-480x384.png)

![Africa’s Elections | In Malawi, food, land, corruption dominate [Lima Charlie News]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/Malawi-election-Food-land-corruption-480x384.jpg)

![Image The Rwandan Jewel - Peacekeepers, Conflict Minerals and Lots of Foreign Aid [Lima Charlie World]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/Rwanda-Jewel-480x384.jpg)

![Image [Women's Day Warriors - Africa's queens, rebels and freedom fighters][Lima Charlie News]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/Womens-Day-Warriors-Lima-Charlie-News-480x384.jpg)

![Image Mali's election - West Africa hangs in the balance over a peace that never was [Lima Charlie News][Photo: Baba Ahmed / AP]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/Malis-election-West-Africa-hangs-in-the-balance-over-a-peace-that-never-was-480x384.png)

![[Silver lining for China in Zimbabwe’s violent elections][Lima Charlie News]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/Screen-Shot-2018-08-02-at-12.51.35-PM-150x100.png)

![Image This Week in Business Intelligence [Lima Charlie News]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/This-Week-in-Business-Intelligence-Lima-Charlie-Business-Intel-Report-150x100.png)