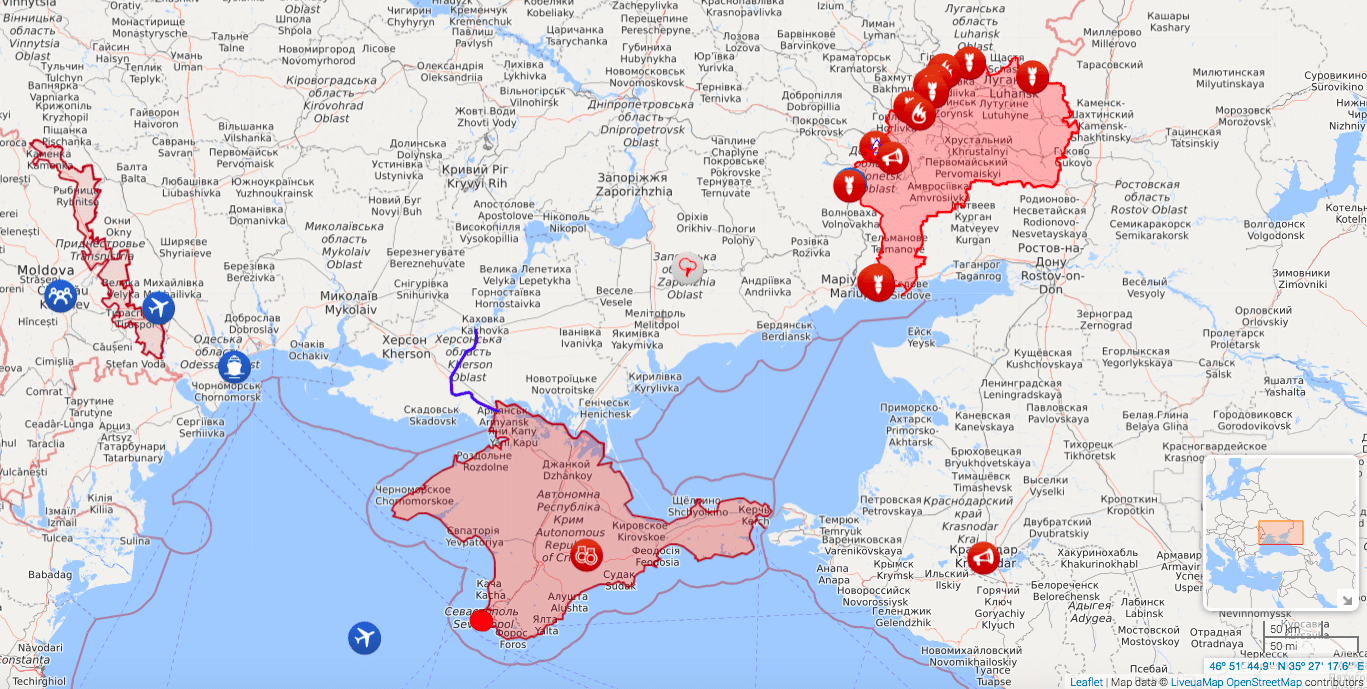

As the conflict between Russia and Ukraine continues, with the threat of a potentially greater conflict emerging, critical factors have emerged that severely mitigate Russia’s ambitions. Along with shifting military capacities, and a shifting reliance on Russian gas, Ukraine has a blossoming relationship with its newest partner – China.

In February 2014, Russian troops began their attack on Ukraine. This attack left most of Eastern Ukraine in the hands of ‘separatists’ and Russian soldiers. The conflict ostensibly created independent separatist states in the Donetsk and Luhansk Oblasts. A sham referendum on the return of Crimea to Russia was then promoted. As Russian President Vladimir Putin celebrated the annexation of Crimea, further threats were advanced towards Ukraine through a sponsored military conflict in Eastern Ukraine.

Each day the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) Special Monitoring Mission reports of battles between Ukrainian and Russian-sponsored troops in the Donetsk and Luhansk regions. Between 2014 and 2018, this military conflict continued in eastern Ukraine, where more than 10,000 people have been killed and thousands displaced.

On November 25, 2018, Russian ships attacked and boarded three Ukrainian vessels in the Crimean port of Azov near the Black Sea. A freighter was placed to block the port, under the claim that Ukraine had violated Russian waters. As these conflicts continue, the underlying treaties and protocols which had been agreed upon to regulate relations between Russia and Ukraine have been violated by Russia at almost every opportunity.

Yet, despite these apparent threats, and the threat of a potentially greater conflict between Russia and Ukraine, critical factors have emerged that mitigate Russia’s aims. Chiefly among them are Ukraine’s increased ability to defend itself against Russia militarily, Russia’s decreased military capacity, a diminishing reliance on Russian gas, and most of all, Ukraine’s blossoming relationship with its newest partner – China.

![Image [A Ukrainian soldier loads a tank with shells near Donetsk. (Photo: Alexei Chernyshev / Reuters]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/Ukraine-fighting.jpg)

Background to the Conflict

In 1992, the USSR broke apart into the Russian Federation and a host of former territories once part of the USSR. These formerly allied states were granted or asserted their autonomy and became independent states. Some joined NATO. The former Warsaw Pact nations were no longer in the thrall of Moscow and went their own way. It was only Ukraine which remained a problem.

In April 1991, Mikhail Gorbachev had prepared a treaty recognising the breakup of the USSR into autonomous republics, but was prevented from signing the treaty by the attempted coup against him in August of that year. On August 24, 1991, the coup had failed and Leonid Makarovych Kravchuk, head of the Ukrainian parliament, passed a motion declaring the independence of Ukraine with him as its first leader. A referendum in December 1991 voted Kravchuk in as the first President of an independent Ukraine.

It was at that point that the U.S. became deeply involved in Ukrainian politics. The U.S.’s primary concern was strategic; the control of Ukraine’s nuclear weapons. At that time, Ukraine was the third largest nuclear power in the world. The U.S. demanded that Ukraine immediately remove its nuclear weapons to Russia where they would be destroyed, and demanded that Ukraine immediately sign the SALT 1 and the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT).

Ukraine’s denuclearization was established with three international treaties. First, Russian President Boris Yeltsin, President Clinton, and Kravchuk signed the Trilateral Accord in Moscow on January 14, 1994, with Ukraine committing to “the elimination of all nuclear weapons, including strategic offensive arms, located in its territory.” The accord was buttressed with paragraphs of American-Russian security guarantees.

The United States and Russia stated that they “would reaffirm their commitment to Ukraine, in accordance with the principles of the CSCE (Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe Final Act), to respect the independence and sovereignty and the existing borders of the CSCE member states and recognize that border changes can be made only by peaceful and consensual means. They also reaffirmed their obligation to refrain from the threat or use of force against the territorial integrity or political independence of any state, and that none of their weapons would ever be used in self-defence or otherwise in accordance with the Charter of the United Nations.”[i]

In a private letter to President Clinton, Kravchuk promised that Ukraine would he nuclear free by June 1996. The three parties met again in Budapest with the U.K. on the 5th of December 1994 and signed the NPT; the Budapest Memorandum.

According to the Budapest memorandum, Ukraine would become party to the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons and effectively cede its nuclear arsenal to Russia. Russia, the U.S., and the UK would:

- Respect Ukrainian independence, sovereignty and existing borders.

- Refrain from threatening or using force against Ukraine.

- Refrain from economically pressuring Ukraine.

- Seek immediate United Nations Security Council action,”if Ukraine should become a victim of an act of aggression or an object of a threat of aggression in which nuclear weapons are used”.

- Refrain from using nuclear weapons on Ukraine.

- Consult with one another should questions arise regarding these commitments.

The Black Sea Fleet and Russian Gas

The next area of concern was the division of the Soviet Black Sea Fleet.

It has always been a key military concern of the Russian State (from the czars onward) to have access to a warm-water port for its navy. Unfortunately for the Russians, the independence of the Ukrainian state left its key warm-water ports (Sevastopol, Odessa, and Nikolayev) entirely under Ukrainian control. The Russians were keen on maintaining their Black Sea Fleet in the Black Sea and operating the large Soviet naval fleet stationed there.

The Ukrainians entered into discussions with the Russians on the division of the fleet of warships in the Black Sea ports and the leasing of Ukrainian ports to the Russian Navy. This change in the status of the Soviet Navy was conducted within the framework of the Treaty on Conventional Armed Forces in Europe (CFE) which was being negotiated between NATO and the Warsaw Pact organisations.

NATO, essentially a euphemism for the Pentagon, played an important role in advising the Ukrainians on its Black Sea Fleet issues. It also generated the creation of the Organisation for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) which, then and now, plays an important role in the relationship between NATO, the Ukraine and Russia.

In June 1993, then Ukrainian President Leonid Kravchuk and Russian President Boris Yeltsin signed an agreement essentially splitting the fleet in half. The agreement quickly fell apart. Ukrainian and Russian military leaders objected to their losses of either ships or ports. In September 1993, and again in April 1994, the Black Sea Fleet agreement was renegotiated.

On 28 May 1997, after nearly five years of controversy, the dispute was finally settled when Prime Ministers Chernomyrdin and Lazarenko signed three intergovernmental agreements. They would divide the fleet’s assets while leasing port facilities in Sevastopol to the Russian Navy. Both nations split the fleet’s ships evenly, while Russia agreed to buy back some of the more modern ships with cash. As a result, Russia ultimately received four-fifths of the Black Sea Fleet’s warships, while Ukraine received about half of the facilities.

The two leaders agreed that Russia would rent three harbours for warships and two airfields for a twenty-year period, for a payment of about $100 million annually. Sevastopol, which had been partly under Russian control, was given to Ukraine.[ii]

Several Russian Black Sea Fleet warships dropped anchor off the Georgian coast during and after the August 2008 Russian armed conflict with Georgia over Abkhazia and South Ossetia. Ukraine, which sided with Georgia and NATO during the conflict, repeatedly said that Russian Black Sea combat ships regularly transported undeclared cargo to the Georgian enclaves and refused to submit customs declarations while crossing Ukrainian territorial waters. The U.S. intervened diplomatically for the Ukrainians to support them in their pressure on the Russians in the Crimea not to use their ships to intervene in the Georgian war. As a result, then Ukrainian president Viktor Yushchenko announced that Ukraine would not extend the lease of the Sevastopol base beyond 2017 and urged the Russian fleet to start preparations for a withdrawal.

The war in Georgia, which was supported by NATO and the European Union, and the threat by the Ukrainians that Russia would lose its warm-water naval bases in Crimea, provoked Russia to retaliate against both Ukraine and the European Union. Russia threatened to cut off supplies of natural gas to Ukraine and Western Europe. In January 2009, these threats were made real when Russia reduced exports of gas to Europe by 60%. Europeans pressed for some sort of a compromise. The dispute was framed as a commercial dispute over prices and payments, but there were far more strategic concerns involved – the Black Sea Fleet. While the U.S. supported the Ukrainians in their defiance of the Russian threats, Europeans pressed for some sort of a compromise which would let the gas flow to their countries.

The Ukrainians were caught in the middle. Europe was desperate for Ukraine to do whatever it took to assuage the Russian gas threat, while the U.S. and its NATO allies pressed the Ukrainians to follow through on ending the Russian leases which allowed them a presence in the Black Sea. Despite the arguments brought forward in favour of each of these policies, a realistic assessment of the situation was made that there was no substitute at that time for Russian gas, so a compromise would have to be reached with Russia.

After much discussion, a compromise was reached and the Ukrainian and Russian parliaments, on 27 April 2010, ratified a deal to extend the lease on Russian naval bases in Ukraine for 25 years after the then current lease expired in 2017. In return, Ukraine received a 30% discount on Russian natural gas. Europe got its gas restored.

This began an accelerated process in Europe to bring the government of Ukraine under its wing and control which could prevent further confrontations on the transport of gas.

Although Ukraine was not very interested at that time in joining NATO, it was interested in establishing a relationship within the aegis of the European Union. During her periods in office, Prime Minister Yulia Tymoshenko had met with representatives of the European Union under the terms of the European Neighbourhood Policy (ENP) which aimed to create a ring of friendly states allied, but not members, of the European Union. She became the voice of Europeans in the Ukrainian leadership.

The U.S. policy was far more confrontational.

The ‘neocons’ who dominated U.S. foreign policy towards Ukraine were loath to lose the opportunity of denying Russia the use of naval bases in the Black Sea, especially after the Georgian War. While vaguely sympathetic to the Europeans, their main enemy was seen as Russia, and any diminution of Russian power and influence was a main concern. Their keymain supporters within Ukraine, President Viktor Yuschenko and Prime Minister Tymoshenko, had just lost control of Ukraine in the national election of a new President, Viktor Yanukovych who had taken office on the 25th of February 2010. Yanukovych was the President from the Donbas region (mainly Russian-speaking) which the Yuschenko and Tymoshenko governments had largely ignored or opposed during their presidencies. That meant that the ratification of the treaty extending Russian occupation of the naval bases was being considered by the Rada (Parliament) under a political majority controlled by Viktor Yanukovych and his Party of the Regions.

The ratification process of the treaty in the Rada took place amid violent protests by the opposition, which called the deal an “act of treason.” Former President Yushchenko criticised the new government for “trading sovereignty for gas.” “What happened in the Supreme Rada is a military usurpation; I am convinced that this is not the end,” he said at a media briefing.

Former Prime Minister Yulia Tymoshenko called on citizens to rise against the current leadership. However, despite protests, the Rada ratified the treaty on 27th of April 2010.

![image [Former Ukrainian President Viktor Yanukovych. (Photo: SERGEI SUPINSKY / AFP)]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/Ukraine-Viktor-Yanokovych.jpg)

In May 2010, President Yanukovych promised to adopt the legislation necessary for creating a free trade zone between Ukraine and the European Union. Further discussions in the next year led to proposals for even closer bonds between the EU and Ukraine. They were broken off, however, when former PM Tymoshenko was arrested and jailed for corruption under politically motivated circumstances by the Yanukovych government. The EU would put the accession of Ukraine on hold until Yanukovych freed Tymoshenko.

Although the EU would agree to accept the accession of Ukraine into the EU, the Rada decided that before ratification there must be a three-way trade agreement which included Russia, to prevent a gas crisis, and ratification of the agreement with the EU was suspended.

This was not only a question of an argument about gas. Yanukovych had refused to sign the EU agreement because his supporters, primarily in the Eastern heartland, were bitterly opposed to its terms as they came with a long list of economic austerity programs. This resulted in considerable backlash within Ukraine at the refusal of the government to sign the agreement, and a repeat of the occupation by protestors of the Maidan Square (now called the Euro-Maidan) resulted.

Ukraine is in a far better place to defend itself against Russia militarily.

The Uprising in the East

A wave of demonstrations and civil unrest began on the night of 21 November 2013, with public protests in Independence Square in Kiev, and demands of closer European integration. These protests expanded, becoming a movement for the resignation of President Yanukovych and his government – a parliamentary coup. There was a great deal of violence in the square, by both the government and the various fascist nationalist parties who made up a substantial part of Yanukovych’s opposition. By 25 January 2014, the protests had been fueled by the perception of “widespread government corruption”, “abuse of power”, and “violation of human rights in Ukraine”.[iii]

As the protests continued, violence intensified, with shootings and beatings on all sides, resulting in about 80 dead and 600 wounded in the clashes at the square.

On February 21, after negotiations between President Yanukovych and representatives of the opposition, aided with mediation by the European Union and Russia, the agreement “About settlement of political crisis in Ukraine” was signed. The agreement provided a return to the constitution of 2004, that is to a parliamentary presidential government, carrying out early elections of the president until the end of 2014. It also provided for the formation of “the government of national trust”. The Rada and the international partners agreed. However, while this seemed generally acceptable as a compromise to the negotiators, the protestors and representatives of the U.S. government insisted on further concessions and the resignation of the President.

At this time, the economic situation in Ukraine was dire. It was running out of money. Ukraine turned first to its erstwhile partners in the EU, requesting 20 billion Euros (US$27 billion) in loans and aid. The EU, however, was only willing to offer 610 million euros (US$ 838 million) in loans, along with harsh conditions on the Ukrainian economy which would have required heavy austerity and changes to the law. On the other hand, Russia offered US$ 15 billion in loans and cheaper gas prices, without the onerous demands for an austerity program.

On the 21st of February 2014, believing that his time was up and that civil war was looming, President Yanukovych abandoned his office, fleeing to Kharkiv and later to Russia. The Rada met the next day to impeach Yanukovych for being unable to perform his duties. A date was set for new elections and, two days later, a warrant was issued for the arrest of the ex-President for the “mass killings of civilians”.[iv]

![Image [Protesters gather in front of burning tires during clashes with riot police in Kiev, Ukraine, on Jan. 23, 2014. (Photo: Valentyn Ogirenko / Reuters)]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/Ukraine-protests-2014.jpg)

By July, Russia continued to strengthen its military force on the border. There were 19,000 to 21,000 troops massed, 14 advanced surface-to-air missile units, and 30 artillery batteries. It was clear that Russia could launch an attack into eastern Ukraine at a moment’s notice. Russia had already launched rockets across the border in support of Ukrainian rebels.

In an effort to prevent further violence, the Trilateral Contact Group on Ukraine was formed, which consisted of representatives from Ukraine, Russia, and the OSCE. The group was established in June as a way to facilitate dialogue and resolution of the strife across eastern and southern Ukraine. Meetings of the group, along with informal representatives of the breakaway Donetsk and Lugansk People’s Republics, took place on 31 July, 26 August, 1 September, and 5 September, 2014. The details of the agreement, signed on 5 September, were called the Minsk Protocols. They agreed to twelve major points:[v]

- To ensure an immediate bilateral ceasefire.

- To ensure the monitoring and verification of the ceasefire by the OSCE.

- Decentralisation of power, including through the adoption of the Ukrainian law “On temporary Order of Local Self-Governance in Particular Districts of Donetsk and Luhansk Oblasts”.

- To ensure the permanent monitoring of the Ukrainian-Russian border and verification by the OSCE with the creation of security zones in the border regions of Ukraine and the Russian Federation.

- Immediate release of all hostages and illegally detained persons.

- A law preventing the prosecution and punishment of persons in connection with the events that have taken place in some areas of Donetsk and Luhansk Oblasts.

- To continue the inclusive national dialogue.

- To take measures to improve the humanitarian situation in Donbass.

- To ensure early local elections in accordance with the Ukrainian law “On temporary Order of Local Self-Governance in Particular Districts of Donetsk and Luhansk Oblasts”.

- To withdraw illegal armed groups and military equipment as well as fighters and mercenaries from the territory of Ukraine.

- To adopt a programme of economic recovery and reconstruction for the Donbass region.

- To provide personal security for participants in the consultations.

Despite the signing of the Minsk Protocols, skirmishes continued. Further talks took place in Minsk to try and resolve some of the issues which were continuing the violence. They would then sign a memorandum to the Minsk Protocols. These included:[vi]

- To pull heavy weaponry 15 kilometres (9.3 mi) back on each side of the line of contact, creating a 30-kilometre (19 mi) buffer zone

- To ban offensive operations

- To ban flights by combat aircraft over the security zone

- To withdraw all foreign mercenaries from the conflict zone

- To set up an OSCE mission to monitor implementation of Minsk Protocol

Despite this, the battles continued. The Minsk Protocols were essentially irrelevant.

In summary, Russia sent troops and equipment to carry on a war against Ukraine using its own troops and surrogates in the Donetsk and Luhansk. Russia annexed Crimea. It has taken effective control of the Azov Sea. It has violated the terms of the Trilateral Accord, the Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe Final Act, the Budapest Memorandum, the Agreement About Settlement of Political Crisis in Ukraine, and the two Minsk Protocols. Now Russia is beefing up its troop levels and naval vessels in and around Ukraine and is threatening further attacks, despite the ‘sanctions’ against Russia by the US and the EU.

Despite these apparent threats and the condonation of Russia’s behaviour by Europeans desperate for Russian gas, there are several factors mitigating Russia’s success.

Ukraine is in a far better place to defend itself against Russia militarily. It has had growing support from a more openly “neocon” foreign policy direction by the United States. There has also been a formidable decline in Russia’s ability to afford or achieve the modernisation of its military equipment, along with a lack of competent manpower. Among this, there has also been a diminishing reliance (despite Nord Stream 2) by Europe for Russian gas.

Most of all, Ukraine has a growing relationship with its newest partner, China.

The Russian Reliance on Ukrainian Military Technology

One of the major difficulties of the Russian military stance towards Ukraine has been the fact that the most developed facilities for military production were located in Ukraine. The Russian Army had been starved of new equipment for over twenty years, and much of what it had available was built in Ukraine.

Ukraine’s military-industrial complex “is the most advanced and developed branch of the state’s sector of economy.” [Ukraine Intelligence & Security Activities and Operations Handbook, Vol. 1: Strategic Information and Regulations; IBP, Inc., November 29, 2017]. There are about 85 scientific organizations specialized in the development of armaments and military equipment, along with an air and space complex, and research, design and development institutes to design and build modern ships and armaments for the Ukrainian Navy. This includes the ability to design and build heavy cruisers, missile cruisers and anti-submarine warfare (ASW) cruisers. Ukraine’s military industrial complex, in conjunction with numerous scientific research institutes and scientific-industrial corporations, has the capacity to develop and produce substantial small arms, communications and automated control systems, intelligence and radio-electronic warfare equipment, and engineer equipment and materiel.

Perhaps the best example is the company Motor Sich. It has been the sole producer of engines for the MI-8 and MI-24 helicopters. It produced these engines for the Russian helicopter industry and a wide range of other military components. The air firm Antonov is based in Ukraine and is one of the major suppliers of aircraft for the Russian Air Force and for Russian arms exports.

The ability of the Russian industry to fill its own needs is compounded by the fact that it needs Ukrainian parts and subassemblies for its exports and consumption. Losing control of the Eastern Ukraine has jeopardised Moscow’s ability to fulfill multibillion-dollar international contracts without Ukrainian inputs.

Antonov also supplies the engines for the jointly-produced AN-148 planes. Ukraine and Russia had plans to produce 150 planes of this type worth $4.5 billion. Other exporters to Russia include Mykolayiv-based Zorya-Mashproekt, which sells several types of turbines to Russia, including those installed on military ships. Another is Kharkiv-based Haroun, which supplies the control systems for Russian missiles. The volume of Russian imports of major conventional weapons in 2009-2013 was 176 percent higher than for the previous five-year period of 2004-2008.

The Yasumasa plant in Dnipropetrovsk is the only service provider for Satan missiles that Russia uses. The Ukrainians are also the main supplier of spare parts which its armed forces desperately need. Russia is scrambling to supply domestic factories with the technology needed to produce these components inside Russia. However, much of the higher inputs of technology, especially in the electromechanical area, are sourced in France, Germany, Britain and the U.S., now effectively closed off to Russia by sanctions. Despite efforts by Russian troops in the Eastern Ukraine, many of the existing plants were attacked and damaged by the rebels of Donetsk and Lugansk. Additionally, the skill set of the Russian factories has been degraded by the demographic crisis of Russia and an ageing population.

When the Ukrainian government decreed that it was banning all military sales to Russia, it was a challenge to President Vladimir Putin and Russia’s generals. Where would they get the turbines for their ships, the missiles for their launchers, the transport aircraft for their soldiers, the engines for their helicopters, their spare parts, et al.? The Russian government tallied up the costs of modernizing its aging military forces equipment and concluded that it would total about $800 billion.

Vladimir Putin had campaigned for the presidency by calling for a rejuvenated Russian military. He published an article in Rosicky Gazeta outlining the massive spending he was intending to pursue in building up the armed forces. Unfortunately, Russia didn’t have the money, and arms manufacturers were in no position to use the funds even if they got them, owing to their state of dereliction and the disappearance of skilled workers in the machine-tool industry.

Not only was supply a problem, there were serious problems with quality.

For example, Uralvagonzavod, the country’s only tank manufacturer is a good case. Putin himself bowed to army pressure to place an order for 2,300 tanks to be built over the next 10 years, despite a statement by General Staff head Nikolai Makarov that the military would not be purchasing any tanks in the next five years due to their substandard quality. In an article in RIA Novosti on 15 March 2012, Ground Forces Chief Col. Gen. Alexander Postnikov said that the most advanced weapon systems manufactured for Russia’s ground forces are below NATO, and even Chinese standards, and are expensive: “The weapon models that are manufactured by our industry, including armour, artillery and small arms and light weapons, fail to meet the standards that exist in NATO and even China.” He said that Russia’s most advanced tank, the T-90, was in fact a modification of the Soviet-era T-72 tank [entered production in 1971] but cost 118 million rubles (over $4 million) per unit. “It would be easier for us to buy three Leopards [Germany’s main battle tanks] with this money,” Postnikov said.

Military modernisation was Russia’s key priority, but it was made infinitely more challenging by the loss of Ukrainian facilities, technology and skilled workers and, of course, international sanctions. President Putin has consistently promised more funds for this endeavour, but has been hampered by several key problems, some of which he cannot control.

For years, Russia has been in the midst of a demographic crisis – and it might be getting worse. There was a 5.4% decline in the birth rate between 2017 and 2018. Up until last year, the population has been holding somewhat steady, but the low birth rate, coupled with low immigration, made 2018 the first year there was a population decline in absolute terms.

Global tables of male life expectancy put Russia in about the 160th place, below Bangladesh. Russia has the highest rate of absolute population loss in the world. The Russian population is ageing, and Russia remains in the throes of a catastrophic demographic collapse. The population is expected to fall to 139 million by 2031 and could shrink 34 per cent to 107 million by 2050. Russia is suffering from a mass emigration of its populace, especially among the educated.

According to the State Statistics Service (SSS), approximately 4.5 million people moved out of Russia between 1989 and 2014. The smallest outflow occurred in 2009 when just 32,500 people emigrated, but the numbers began rising again after 2011, and in 2014 once again reached 1995 levels. The situation has gotten significantly worse. “Russian government statistics show a sharp upturn in emigration over the last four years … Almost 123,000 officially departed in 2012, rising to 186,000 in 2013, and accelerating to almost 309,000 in 2014 after the annexation of Crimea and even more in 2015.” [viii]

![Image [Servicemen march during Ukraine's Independence Day military parade in central Kiev (Photo: Valentyn Ogirenko / Reuters]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/Ukraine-military-parade.jpg)

Bloomberg Economics calculations suggest some $750 billion in Russian assets moved offshore over the last 25 years. The bleeding appears to have slowed, though it’s unclear if this reflects tighter controls and mounting geopolitical risk, or if the flows have simply been getting harder to track.[x]

The cost of the continuing war in Ukraine and the massive bleed of Russian military resources in Syria are also taking a heavy toll on the Russian budget.

The cost of rebuilding Syria will make a heavy dent in Russia’s economic well-being. However, it has committed itself to a wide range of improvements in its military capabilities. This despite Russia’s lack of adequate shipyards, missile factories, available conscript manpower, essential electronic and guidance systems and subsystems blocked by sanctions. The burden of maintaining aged and decrepit equipment and an ever-expanding effort to extend its political reach into the Middle East, Africa and Latin America has increased dramatically.

Much of this is the traditional Russian policy of bluff and bluster but, with the official burial of the INF Treaty, it is engaged in some expansion of its intermediate range missile systems. Some of these efforts towards greater capability appear to be directed against Ukraine as Russia is stepping up its threat level as Ukraine prepares for elections.

Ukraine and Its New Friends

While Ukraine has continued its daily confrontations with the forces of the Donetsk and Luhansk Regions and Russian forces along its littoral Black Sea and Sea of Azov coasts, the U.S. passed a $47 million U.S. military-aid package for 2018. The U.S. confirmed in March 2018 that it had delivered to Kyiv 210 Javelin anti-tank missiles and 37 Javelin launchers, as well as military trainers in their use and deployment. These had already had a marked effect on the deployment of tanks by Russia and the rebels. However, the Russian pressure on Ukraine has not ceased.

In mid-December 2018, Russia moved military convoys north on the Simferopol-Armyansk highway toward the border between Kherson Oblast’ in Ukraine and Crimea. Later that month, Russian submarines of the Black Sea Fleet conducted drills in the Black Sea to practice covert movements while submerged. Russia also shifted fourteen Su-27 and Su-30 fighter jets to Belbek Airbase near Sevastopol. This was, presumably, to begin an assault on the Dnepr River canal which provided fresh water to the Crimea before the Ukrainians blocked it. The Russians built a bridge over the Kerch Strait to bring supplies to Crimea; an unsteady bridge which is not expected to last too long because of the seismic conditions in the Strait, but it is low enough to block many of the commercial vessels shipping goods to and from the Ukrainian ports of Mariupol and Berdiansk.

The U.S. and EU have been pushing back against this attempt by Russia to strangle Ukraine economically, by sending vessels and missile cruisers to the area. Yet, Russia hasn’t stopped its continued pressure on Ukraine.

However, there is a new dimension to the power equation with the arrival of a large Chinese presence.

China has increased its involvement in Ukraine, using development assistance through its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) as a rationale for its efforts. China’s main goal is economic benefits for itself and as a foil for the brake on Russian aggression which would threaten the BRI. China is strengthening its position in Eastern Europe to gain an advantage in its relations with Russia, the EU and the U.S.

For China, Ukraine is an important BRI partner. For Ukraine, China is its main Asian economic partner. In 2011, the countries signed a strategic partnership. By January 2015, Ukrainian President Petro Poroshenko and Chinese leader Xi Jinping discussed increasing cooperation during the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland. In September 2017, Ukraine’s foreign minister, Pawlo Klimkin, paid a visit to China, and then last December, Ma Kai, China’s vice premier, visited Kyiv.

China’s activities in Ukraine are ideal for its BRI mostly because of Ukraine’s transit-state position and its free-trade agreement with the EU. One of the main elements of BRI is establishing new railway connections between China and Europe. In 2016, Ukraine launched a test of a new rail-ferry line transporting goods between the Black and Caspian seas, but using other connections that exclude Russian territory. [xi]

Chinese investment has proved to be much less onerous than the strict rules of the EU and the Bretton Woods agencies which insist on managing “Ukrainian corruption”. China aggressively competes with Ukraine’s Western partners for a strong foothold in this important frontier economy, often with much less restrictions.

Combined with free trade agreements with the EU and Canada (the EU has become Ukraine’s largest bilateral trading partner at 30 billion euros [$35 billion] per year), along with steady U.S. trade, Ukraine remains a highly attractive partner to China and Chinese companies. With Beijing having pledged at least $7 billion for major Ukrainian infrastructure projects, Chinese companies, which often come in under budget and complete large projects ahead of schedule, are now major competitors with Europe for big infrastructure projects.

On the south-eastern Black Sea coast, the China Harbor Engineering company completed a $40 million dredging operation to give bigger ships access to Yuzhny port, while it’s been reported that ports in Odessa, Chornomorsk, and Izmail may also benefit. While Chinese companies tackle Ukrainian infrastructure projects such as coastal highways and roads built to withstand the burden of heavy, grain-laden trucks, others are investing in new grain silos and port elevators to help with transportation logistics. [xii]

China clearly sees Ukraine as a special area of interest, both for its location and for its agricultural productivity.

Along with direct access to the Danube River, the Black Sea and the Sea of Azov, Ukraine also has 22,000 kilometres of interconnected railway to Europe. With bilateral trade between Ukraine and China now exceeding US$7.6 billion a year, Ukraine also supplies China with the bulk of its corn consumption. A major Chinese agricultural giant, Noble Agri, has two assets in Ukraine, a sunflower seed processing complex in Mariupol, and a grain facility and port terminal in Mykolaiv which boasts a capacity of 2.5 million tons per year and storage capacity of 125,000 tons. Ukraine is the only European country where Noble Agri has a presence, while it competes worldwide with US companies like Cargill, Monsanto, and Bunge.[xiii]

![Image [China Harbor Engineering Company vessels at the Yuzhniy Port in Odesa Oblast. Ukraine, Europe and Africa are growing targets of Chinese investment. (Photo courtesy of TIS)]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/China-Harbour-Engineering-Company-Ukraine.jpg)

(Photo courtesy of TIS)]

The most important conflict between the Russian military and President Putin may have arisen from Putin’s policy towards China.

Putin’s administration has been making every effort to engage with China, by asking for assistance to join with Russia as a consumer of its energy exports, as well as a builder of pipelines, ports and railroads. This includes growing a financial partnership. These efforts have put President Putin in direct conflict with the Russian military, which views China as a strategic enemy.

For decades there has been an intense competition between the two nations in their border regions, which at times has resulted in conflict and disputes over land. After a treaty was completed in November 1997 establishing the border between the two countries, and a 2004 Complementary Agreement returning some territory to China, relations have been strained since then as there is an increasing imbalance between the two sides; militarily, economically and in terms of manpower.

Russia has a very serious problem with China. There are too few Russians in the regions of Khabarovsk and Primorsky Krai to match the Chinese. Russia is being depopulated at a prodigious rate with many of those who lived in Siberia and the Russian East (Dalnevostok) moving West to the cities across the Urals. There are not enough Russians to conduct the business that will need to be done on a project as vast as the extraction of oil, the building of a pipeline and the establishment of roads, ports and infrastructure in that region. Even Russians admit that this work will be performed by Chinese labourers.

Russian companies do not have the manpower, the working capital, or the inclination to perform this infrastructural work. It has not improved with the continuing depopulation of the region. The dependence on Chinese manpower has had an important effect on Russia’s purported tilt towards China.

Russian politicians may think it makes sense to shift focus to co-operation with China, but the Russian military has no such compulsions. Russia’s military has voiced concerns over its naval bases in Sovetskaya Gavan and Bolshoi Kamen not far away. Officials were surprised that President Putin appears more concerned about NATO (6,000 miles away) than about China, a nation with a population of billions that shares a border a quarter of a mile away across the Amur and the Ussuri Rivers. There are concerns that Russia would not be able to prevent a Chinese decision to take back some of its lost lands in the Russian Far East. This issue has been compounded by the current Chinese military and economic expansion in the Arctic and the growth of China’s military exports to the world of products derived from Russian designs, but improved upon by the Chinese.

We are no longer bound by any limitations either on the range of our missiles, nor on their power – let the enemy know about it, too. We need high-precision missiles and we are not going to repeat the mistakes of the Budapest memorandum.

-Ukrainian President Petro Poroshenko

The Ukrainian Response

The most important aspect of the Ukrainian response to the advances by China is in its military-industrial complex negotiations with the Chinese. China is trying to buy or control the vast military capability of Ukraine, which was denied to Russia after its invasion of Ukraine.

One key area of interest is helicopter manufacturing and Ukraine has the firm, Motor Sich, that is a world leader in building helicopter engines and other components, as well as turbine engines for warships. Ukraine and its Western partners are not willing to allow what many consider a national treasure to become Chinese owned. China, which has been buying components from Motor Sich since the 1990s, would greatly benefit from its trade secrets and key personnel. As long as Russia occupies Crimea and Donbas that business relationship remains blocked.

On the other hand, Ukrainians feel a new door has been opened for them by the U.S. leaving the INF Treaty. In March 2019, President Petro Poroshenko said that Ukraine was no longer bound with some limits regarding missile range and that Ukraine would now seek to develop high-intermediate precision missiles. Ukraine has the technology and the tools for this already.[xiv]

Poroshenko stated, “We are no longer bound by any limitations either on the range of our missiles, nor on their power – let the enemy know about it, too. We need high-precision missiles and we are not going to repeat the mistakes of the Budapest memorandum.”

With the resurgence of Ukraine’s defence industries, the rise of a working relationship between Ukraine and China, and the increasing active participation of the U.S. in supplying Ukraine with increased lethality, there are limitations of Russia’s ability to project hard power against the Ukrainians. Regardless, in no way does this diminish or impede Russia’s cyber efforts, or the use of trolls, hackers and subterfuge to alter the political destiny of Ukraine or its ability to choose its leaders without undue interference. That is a battle which will continue in the near future.

Dr. Gary K. Busch, for Lima Charlie News

[Edited by Anthony A. LoPresti]

[Subscribe to our newsletter for free and be the first to get Lima Charlie World updates delivered right to your inbox.]

Dr. Busch has had a varied career-as an international trades unionist, an academic, a businessman and a political intelligence consultant. He was a professor and Head of Department at the University of Hawaii and has been a visiting professor at several universities. He was the head of research in international affairs for a major U.S. trade union and Assistant General Secretary of an international union federation. His articles have appeared in the Economist Intelligence Unit, Wall Street Journal, WPROST, Pravda and several other news journals. He is the editor and publisher of the web-based news journal of international relations www.ocnus.net.

Sources

[i] U.S. Department of State Dispatch:Trilateral Statement by the President of the United States, Russia and Ukraine in Moscow on January 14,1994

[ii] Memorandum on Security Assurances in connection with Ukraine’s accession to the Treaty on the NPT, UNDOC S/1994/1399

[iii] “Yanukovych Offers Opposition Leaders Key Posts”, RFE/RL 25 January 2014

[iv] “A warrant out for Viktor Yanukovych’s arrest, says Interior Minister”, Guardian. 24 February 2014

[v] “Minsk Protocol” (Press release) (in Russian). Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe. 5 September 2014

[vi] “Memorandum of 19 September 2014 outlining the parameters for the implementation of commitments of the Minsk Protocol” (Press release) (in Russian). Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe. 19 September 2014

[vii] http://www.unz.com/akarlin/russian-demographics-in-2019/

[viii] Yelena Mukhametshina, Russia Must Deal With Catastrophic Brain Drain , Moscow Times, October 7, 2016

[ix] Crime Russia, “Capital outflow from Russia doubles since beginning of 2019, exceeds $18 billion” 12/3/19

[x] https://www.bloomberg.com/opinion/articles/2019-03-12/u-s-is-no-1-in-arms-sales-as-russia-loses-market-share>

[xi] Marcin Przychodniak, “China’s Involvement in Ukraine’s Economy Vis-à-vis Russia”, PISM 22/1/18

[xii] Jack Laurenson, Ukraine: “China Flexes Its Investment Muscle”, Diplomat,27/6/18

[xiii] Olena Mykal, “Why China Is Interested in Ukraine”, Kyiv Post, 10/3/16

[xiv] Interfax-Ukraine, “Poroshenko: Ukraine has no plans to repeat mistakes of Budapest memo, country needs high-precision missiles”, March 9, 2019

In case you missed it:

![Image Is Russia Failing in Ukraine? A Diminishing Threat [Lima Charlie News]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/Russia-failing-in-Ukraine.png)

![Image Russia and China’s 'hybrid warfare' - Does the West even care? [Lima Charlie News]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/Russia-China-Hybrid-Warfare-02-480x384.png)

![Image War in Eastern Ukraine and the New Heroes of ‘Novorossiya’ (New Russia) [Lima Charlie News]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/Donbass-MAIN-01-480x384.png)

![Blossoming Russo-Turkish alliance leaves U.S., NATO behind [Lima Charlie News]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/Russia-Turkey-alliance-leaves-U.S.-NATO-behind-480x384.png)

![Image Murder, genocide, politics and the almost surrender of Radovan Karadžić [Lima Charlie News][Lima Charlie World]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/Radovan-Karadzic-001-480x384.png)

![Image The Alevis Dilemma [Lima Charlie News]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/Alevis-Erdogan-480x384.png)

![Image Russia and China’s 'hybrid warfare' - Does the West even care? [Lima Charlie News]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/Russia-China-Hybrid-Warfare-02-150x100.png)

![Image War in Eastern Ukraine and the New Heroes of ‘Novorossiya’ (New Russia) [Lima Charlie News]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/Donbass-MAIN-01-150x100.png)

awesome content!