World Press Freedom Day has us asking ‘What is the state of free press in democracies worldwide, and why has America’s free press ranking dropped?’

World Press Freedom Day – a day proclaimed by the United Nations (UNESCO) to “celebrate the fundamental principles of press freedom, to evaluate press freedom around the world, to defend the media from attacks on their independence and to pay tribute to journalists who have lost their lives in the exercise of their profession” falls on May 3rd. World Press Freedom Day is critical to remind ourselves that the very bedrock of every healthy democracy is a free and vibrant press.

Which is why it’s also important to remind Americans that according to this year’s Reporters Without Borders World Press Freedom Index, a ranking of countries based on their state of media freedom, the United States dropped 3 notches lower than last year. The U.S. is now 48th in the world with regard to press freedom – beneath Romania and above Senegal. This drop changes the U.S. ranking to “problematic”, where rankings range from good, to fairly good, to problematic, bad and very bad.

The index is determined by pooling the responses of experts worldwide to an 87 item questionnaire that has been translated into 20 languages. It addresses seven criteria that include pluralism (the degree to which opinions are represented in the media), media independence (the degree to which the media is able to function independently of political, governmental, business and religious influence), transparency (the transparency of the institutions and procedures that affect the production of news and information), and abuses (data gathered about abuses and acts of violence against journalists and media).

The top three? This year, Norway ranked first for the third year in a row, with Finland ranking second and Sweden ranking third. The bottom three? Eritrea falls in at 178, followed by North Korea at 179 and Turkmenistan at 180.

In its U.S. review, Reporters Without Borders (Reporters Sans Frontières – RSF) was careful to mention President Trump’s labeling of the press as “the enemy of the people”, the Trump administration’s attempts to block and even revoke White House access from certain media outlets, and the president’s consistent verbal attacks on what he deems “fake news.” Just this February, reporters from the Associated Press, Bloomberg News, the Los Angeles Times and Reuters were banned from covering President Trump’s dinner with North Korea’s Kim Jong Un because of what White House press secretary Sarah Sanders said were “sensitivities over shouted questions in the previous sprays.”

Also mentioned in the RSF freedom index report are press impingements that predate the Trump Presidency, such as the utilization of the Espionage Act by the Obama Administration to prosecute whistleblowers who leak information of public interest to the press, the fact that there is still no federal “shield law” guaranteeing reporters’ right to protect their sources, and the arrests of journalists during protests.

Aside from the U.S.’s three point ranking drop two years into the Trump Presidency, the Trump Administration’s attitude toward the media is nothing if not consistent.

So what has changed?

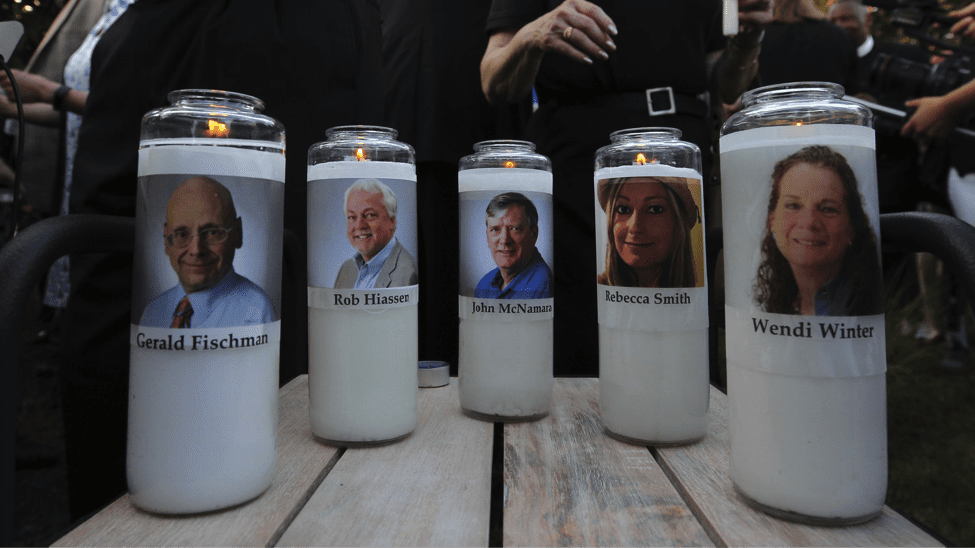

Mass shootings targeting journalists already have significant implications for the press, such as the January 2015 Charlie Hebdo attack, but the American phenomena of non-political mass shootings targeting the press is something new.

Also factoring into this year’s decline are disturbing developments over the Department of Homeland Security’s (DHS) targeting of journalists. In March, a secret DHS database of journalists and advocates who were critical of the DHS’s border enforcement policies leaked to the press. The reporters on the list were subject to harsher treatment during otherwise routine border crossings. Over 100 civil liberties organizations, including RSF, signed a letter to the DHS calling them out for this action.

But what about the rest of the World?

In its summarization of the key findings of the 2019 Press Freedom Index, RSF illustrated that although the deterioration of press freedom is global, the most precipitous declines occurred in countries with otherwise strong democratic institutions. Specifically, RSF called out the tenor of political debates as being a key factor in this year’s findings.

“If the political debate slides surreptitiously or openly towards a civil war-style atmosphere, in which journalists are treated as scapegoats, then democracy is in great danger,” RSF secretary-general Christophe Deloire said. “Halting this cycle of fear and intimidation is a matter of the utmost urgency for all people of good will who value the freedoms acquired in the course of history.”

This means that the most precipitous declines occurred in the Americas and Europe, the regions with the greatest proportion of people participating in free, if increasingly contentious, elections.

For example, Spain has seen a fundamental shift in the treatment of the press over the last two years. First, the pro-Catalan independence partisans were hostile to media covering the referendum and subsequent independence efforts in terms of intimidation of TV crews reporting on events and in online harassment.

The new right wing Vox party, which rose partially in response to the Catalan Referendum, held rallies marked by the shouting of verbal abuse at members of the press. Exemplifying a “civil war-style atmosphere,” one of the primary sources of Vox’s ire at the media was a perception that the press had been too sympathetic to the Catalan independence movement.

“There’s no longer any trust in the press,” Manuel Mariscal, the head of Vox’s online accounts, told El Pais. “We are turning into our own communications channel.”

Vox has increased its media platforms since it launched in 2014, capitalizing on the publication of short (under 1 minute) video content. These videos are easily shareable, and the party uses them to build their platforms. Although media repeatedly call out the party’s content as misinformation, their platform helped them communicate directly with their voters and effectively bypass the media. In spite of Spain’s electoral commission banning Vox from participating in televised debates, the party gained 24 seats in the parliamentary elections.

Brazil’s new democratically elected President Jair Bolsonaro, who speaks via weekly Facebook streams, is a poster boy for animosity toward the press.

“The elections are over. Enough lies. Enough fake news. Really, we’re in a new era,” President Jair Bolsonaro said, opening an interview the day after he was elected in October 2018. The president went on to express admiration for the press, before he threatened to withdraw government advertisements from Folha de São Paulo, one of Brazil’s most widely circulated newspapers. “That Newspaper is done.”

![Image Current President Bolsonaro of Brazil performing one of his weekly Facebook live streams during his campaign.]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/Bolsonaro-social-media.png)

The bottom line is that the symbiotic relationship between the press and politicians, where the press gets access and the politician gets exposure, is breaking down because politicians can get millions on their own. And this isn’t just true in Europe and the Americas, notably, Tanzania’s President John Pombe Magufuli, nicknamed “bulldozer” has replicated these activities.

At question, however, is whether and how news consumers can learn whether what they are reading, seeing and hearing is accurate.

Innovative Anti-democracy Technologies Arise

Although RSF is most concerned with the politicalized animosity directed at reporters, governments in less developed, or less free, countries are becoming increasingly effective at censorship.

Again, thanks to new technology.

South Asian countries like Pakistan, India, and Myanmar are plagued by fake information spread by social media, engendering a hostile environment for reporters.

The RSF report focused special attention on two Reuters journalists that were handed 7-year jail sentences for reporting on Myanmar’s Rohingya and the role that social media fear-mongering played in normalizing repression.

China, which ranked 177th of 180 in the World Press Freedom Index (just two above North Korea), has a much more highly developed economy than most poorly ranked countries, and an ever growing surveillance apparatus. With 200 million government-run cameras, China’s surveillence of its own citizens – and journalists – is becoming increasingly sophisticated.

In February 2018, an independent journalist found an unsecure government database monitoring Xinjiang province. Utilizing facial recognition and AI, the government was tracking the locations and purchases of 2.6 million people – live. What is more, recent New York Times reporting has exposed that China is exporting its surveillance models.

In Russia (ranked 149), according to RSF, “Leading independent news outlets have either been brought under control or throttled out of existence” and “more journalists are now in prison than at any time since the fall of the Soviet Union and more and more bloggers are being jailed.”

In a technology coup, on April 22nd, Russian parliament’s upper house approved, and on May 1st President Putin signed into law new measures that would enable the creation of a national internet network able to operate separately from the rest of the world. This “sovereign” Russian Internet controlled by the Kremlin would require ISPs to direct traffic through a centralized system of devices controlled by the state, with approved Internet exchange points, and to use a national domain name system (DNS). According to RIA-Novosti, the law also calls for the creation of a monitoring and management center supervised by Roskomnadzor, Russia’s telecoms agency. No doubt “free press” will have a new meaning if and when the system becomes operational.

Success stories?

Although press freedom is deteriorating globally, there were some success stories.

For example, Ethiopia, which jumped up 40 places, composed a multi-ethnic governing coalition in an effort to end strife in the Oromo ethnic group. The new government released all formerly imprisoned journalists, unblocked web access to some 264 news websites, and facilitated the repatriation of dozens of Ethiopian language news services based in other countries. However, the increase only brought them to 110th, and over the summer a regulator chastised the two major television networks for inadequate coverage of a ruling party rally.

Armenia’s ‘Velvet Revolution’ last spring caused it to jump 19 places in the index; however, the new leader of the country, who is a former journalist himself, hasn’t hesitated to utilize the language of “fake news” to attack critical coverage.

Malaysia’s left wing multi-ethnic parties gained power for the first time, in no small part because of investigative journalism uncovering a $4.5 billion embezzlement scandal, resulting in the ouster of Malaysia’s United Malays National Organisation (UMNO) party, the ethno-nationalistic party that had power for some 70 years. The incoming prime minister fulfilled his campaign promise to repeal a draconian anti-fake news law. However, the new prime minister, 93-year-old Mahathir bin Mohamad, a former UMNO leader, ruled the country as a practical dictator from 1987 to 2003, undermining press freedom during his last time in office.

With the support of considerable financial backing from the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), Gambian citizens were able to expel the dictator Yahya Jammeh in 2017. Press freedom is increasing in Gambia thanks to lawsuits challenging Jammeh’s anti-press laws.

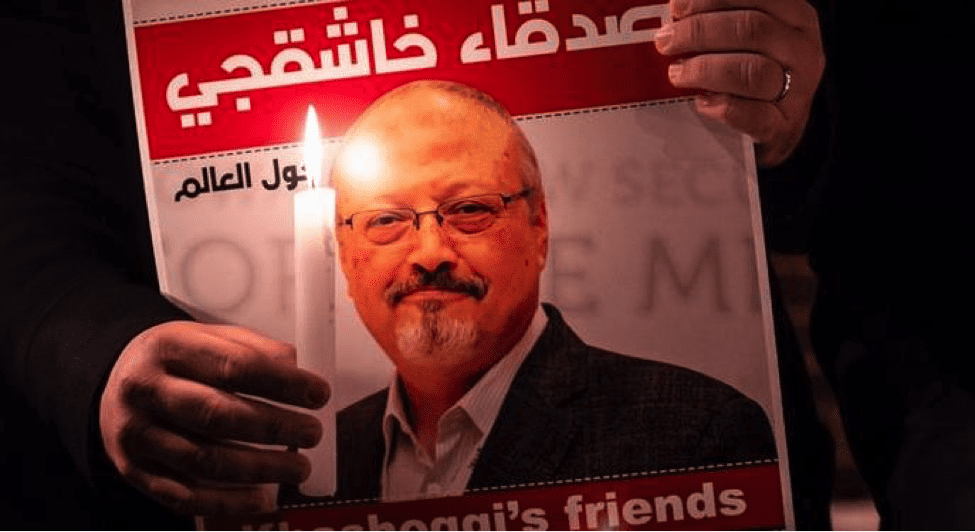

In the Arab world, Tunisia, with one of the freest media environments in the region, is continuing its struggle to live up to the expectations set by the 2011 Arab Spring and the hundreds of millions in foreign aid that followed. These gains, however, are only positive relative to countries in the rest of the MENA region (such as Iran – ranked 170 or Saudi Arabia – ranked 172), where journalists who face prosecution are often left to fend for themselves, numerous media outlets face financial insolvency, and efforts to report on negative government activity are frequently stonewalled.

In Asia, press freedom is also being undermined in countries that are heavily linked to China’s economy – such as former bastions of press freedom Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Singapore.

We wrote on Press Freedom Day 2017:

[T]he reason we created Lima Charlie, is the mandate proclaimed in our mission statement: “Lima Charlie journalists seek to investigate and report the truth, with unparalleled access and a noble eye towards promoting peace, understanding, and positive political engagement.”

We believe to our core that it is indeed the media’s role, our role, to work towards the advancement of peace, understanding and positive political discourse, crucial to any true democracy. For the men and women in our team that have seen conflict firsthand, that have made great sacrifices to ensure peace and security, and that have fought to protect a noble and free press, the role of the media “in advancing peaceful, just and inclusive societies” is an equally honorable mission. We strive to accomplish this mission every day.

We hope that by the time we report on World Press Freedom Day 2119 we have remained true to that mission.

-Editors, LIMA CHARLIE NEWS / LIMA CHARLIE WORLD

[John Sjoholm, Diego Lynch, and Anthony A. LoPresti contributed to this article]

[Main image: Photo by Oliver Contreras / SIPA]

[Subscribe to our newsletter for free and be the first to get Lima Charlie World updates delivered right to your inbox.]

Lima Charlie World provides global news, featuring insight & analysis by military veterans, intelligence professionals and foreign policy experts Worldwide.

For up-to-date news, please follow us on twitter at @LimaCharlieNews

In case you missed it:

![Image World Press Freedom Day has us asking ‘What is the state of free press in democracies worldwide, and why has America’s free press ranking dropped?' [Lima Charlie News]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/World-Press-Freedom-Day-01.png)

![STRATEGIC OPTION | Syrian Endgame - The Hard Truth [Lima Charlie News][Photo: Bulent Kilic]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/STRATEGIC-OPTION-Syrian-Endgame-e1558501175322-480x384.png)

![Image Memorial Day may soon be a remembrance of democracy and those who had the courage to defend it [Lima Charlie News]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/Memorial-Day-may-soon-be-a-remembrance-of-democracy-and-those-who-had-the-courage-to-defend-it-Lima-Charlie-News-480x384.png)

![The Mind of Bolton - AUMF and the New Iran War [Lima Charlie News]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/Inside-the-mind-of-Bolton-Lima-Charlie-News-main-01-480x384.png)