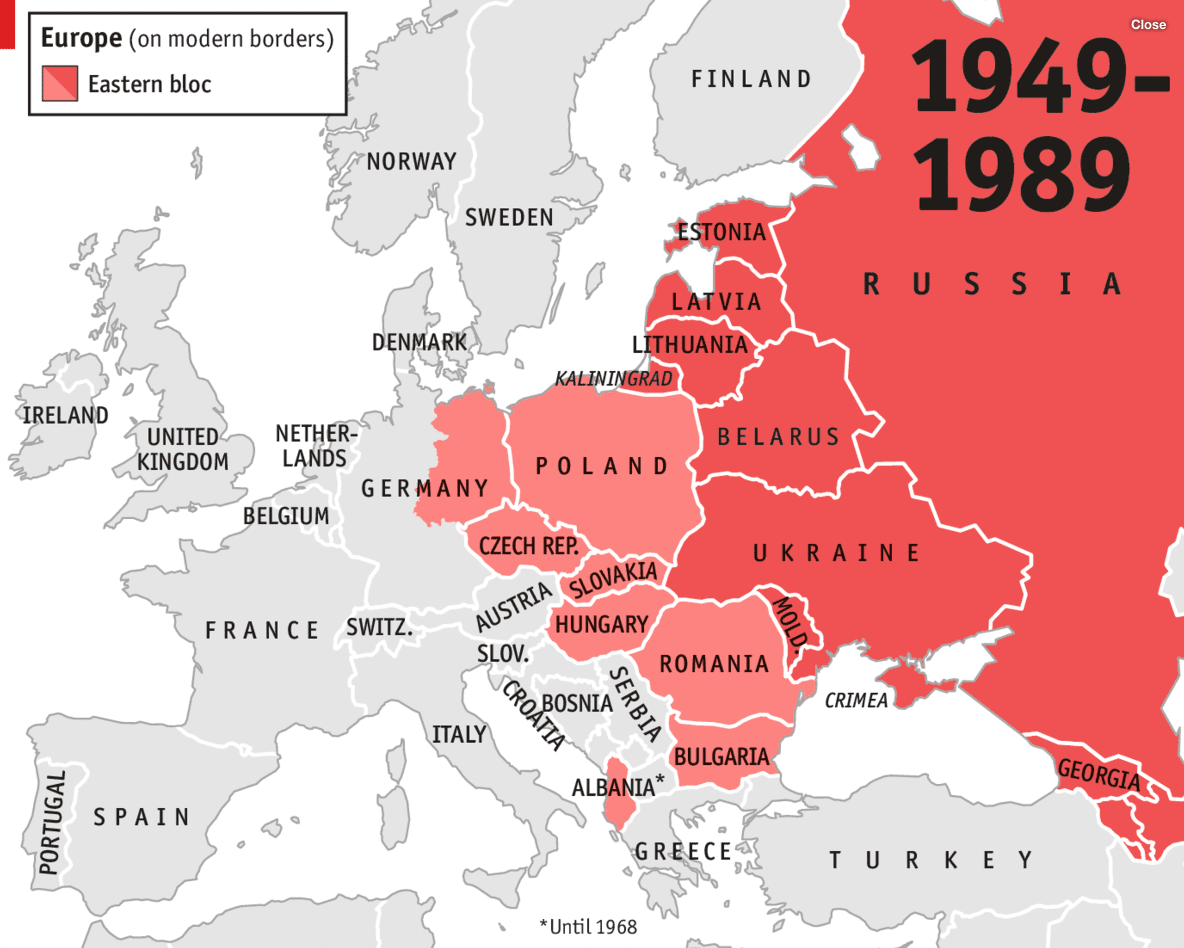

On the 50th anniversary of the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia after the failed Prague Spring, Dr. Gary K. Busch reflects on the Cold War and old East-West rivalries fought not on the battlefield, but in factories, ports, schools, universities and cultural centres across the world. Part 1 of a 2 part series.

It’s hard to believe that it was fifty years ago when the Soviets invaded Czechoslovakia and put a stop to the evolution of Czech self-governance. There have been endless articles, books, films and media presentations along with tomes of academic research describing the precursors, perpetrators, motives and consequences of this demonstration of wanton power by the USSR against a fellow member of Comecon and the Warsaw Pact.

I don’t presume to add to this avalanche of scholarship. I only would like to touch upon the several aspects of this invasion which have passed, unnoticed, in these descriptions of the Prague Spring. I was lucky, as a foreigner, to witness first-hand these events as they developed, and played a very minor role in shaping the configuration of the response of various elements in the Czech institutions to the challenges they faced.

In reading the many learned analyses of the Prague Spring and the studies on the impact of the Cold War on international politics one fact stands out – for most scholars, academics and analysts the term Cold War is viewed as a general rubric for the competition between the U.S. and its allies in the West, against the Soviet Union and its allies around the world. The Cold War has been described as a game of tactics and coercion conducted by nation states under the umbrella of Mutual Assured Destruction where nuclear attacks were the ultimate weapons.

This interaction by sovereign states may, indeed, be the vital component of the Cold War struggle. Yet this was not really the arena in which most of the Cold War interactions took place.

![Image [Russian Cold War period propaganda poster. "We demand the Peace but if you touch us ..."]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/Cold-War-01.jpg)

Without understanding the crucial dimensions of these conflicts any real understanding of the term “Cold War” is woefully deficient.

In most societies across the world there are certain groups which are identified as “national”. They transcend the several ethnicities, language groupings, regional identities of the populace and form themselves as national organisations. These draw in people from all the national diversities into larger units. Prime among them are: the army; the labour unions; the student groups; the intellectual and cultural elites; the aggregations of organised crime; and the religious groups.

Any foreign power which can influence the policy direction of any or all of these groups will have a major effect on the political activities of the nation and its alliances.

This is why the U.S. and the KGB/GRU had massive programs of overt and covert assistance to these groups. That is, to a large extent, where they fought the Cold War.

The Trade Union Battlefront

A crucial element in the conflicts over Soviet rule in post war Eastern Europe was the battles conducted within and through the trade union movements in these nations. They were at the heart of almost all the struggles and the common leitmotiv of the move towards European liberation. They provide a unique focal point for understanding the nature, and often the loci of the conflicts.

The following pattern is one which was repeated in virtually every nation in Eastern Europe after World War 2. The control of the trade union movement was the lever for the transition from a government of national reconciliation to one firmly under communist control.

First, a new government of national unity would be installed; a coalition of centrist, socialist and communist political parties. Most often the communists would take control of the Ministry of the Interior. Infiltration and control of the trade unions would result in communist cadres taking important union posts. Soon mass demonstrations in support of political aims would win for the unions a role in national economic planning. The Ministry of the Interior would then find numerous “plots against the state” by members of the non-communist parties.

The unions would clamp down on the press by refusing to print opposition newspapers. They would even refuse to transport provincial papers to the capital. They would precipitate strikes within the plants and offices which, by their political nature, would effectively split the socialist movement into two factions, one allied with the communists and one opposed.

Soon after, the trade unions would be used to create a crisis. The communists would then step in as the party able to heal the breach. The communists and the left socialists would form a government together, ousting the centre and right parties.[i] Then, after an interval, the communists would purge the government of the socialists.

The Communist Seizure of Power In Czechoslovakia – A Model For Eastern Europe

Pre war Europe was largely a strained political compromise between the forces of the Liberal, Christian Democrat and Smallholder parties of the right and centre and their opponents of the socialist and social democrat left. The rise of fascism wreaked havoc among the forces of the left, especially the socialists, who were killed or imprisoned in large numbers. The fragile compromise or balance between the two wings of a democratising Europe was broken during the war, leaving a vacuum in its wake.

The occupying powers were faced with restoring domestic order and a viable economic infrastructure. A key element in this process was inevitably the trade union movement; but the movement had not itself emerged unscathed from the war. Many unionists were killed or imprisoned; others had been discredited by their collaboration with the Germans. Still others spent their war in the USSR to which they had escaped following the collapse of the Hitler-Stalin Pact. These returned to their native lands backed by the might of the occupying Red Army and assumed key leadership posts.

In the immediate post war years in Eastern Europe the Soviet occupying powers tried to effect a transition from the war torn and wrecked nations they had taken under their “zone of influence” into docile partners in a wider Russian zone. A key area of conflict was Czechoslovakia. In Czechoslovakia the wartime conflict had not destroyed much of the industry or its relative prosperity. Czech political relations with the Allied powers in London were especially good. In May 1945 the Czech government in exile of President Benes returned to Prague to govern as a coalition, with the approval of the Allies (including the USSR after communists had been included in the coalition). Once the Czechs succeeded in expelling their German and Hungarian minorities there were many unoccupied farms and the demand for skilled labour was great.

The political party structure, however, was decimated and only the communists had maintained a relationship with their cadres during the war years and the early days of Soviet occupation. The largest party, the National Socialists, which had rejected both the Second and the Third International’s offers of membership, was decimated during the war (only Jaroslav Stransky was left of the old executive committee and the new leadership was either the London group or followers of Petr Zenkl and Vladimir Kraina – militant anti-communists). The Catholic People’s Party kept its pre-war leader (Monsignor Jan Stramek) but was split between rival factions.

In the worst shape were the Social Democrats, whose leadership was dead or too old to rebuild the party to its former strength. The new leadership was left to young radical socialists, led by Zdenek Fierlinger, who pledged themselves to cooperation with the communists (in fact some observers saw as the existence of the Social Democrats as a pure election ploy because the initial party representation accorded 25 per cent of the votes to each of the four major parties – the Social Democrats and the Communists together controlled at least 50 per cent of the votes).

The Czech trade unions were badly split before the war; each party had its own trade union affiliate. With the German occupation, they were united into two national labour fronts. The first was for industrial workers; the second for white collar employees. These unions were collaborationist organisations run by the German ministry’s special section for foreign labour. The Czech workers were treated comparatively well by the Germans who valued their high productivity. By spring 1945 there were over 500, 000 workers paying dues to the German-sponsored unions. With the return of the new government in May 1945 the Communists took over control of the German-sponsored unions, renamed them the Revolucni Odborove Hnuti (ROH), and placed an old-line communist, Antonin Zapotocky at its head.

The Russians flew in Josef Kilsky from his place of refuge (Kilsky had been a key organiser in the old Profintern) and made him organisational secretary. The ROH was a pyramidal structure with the leadership firmly in the hands of the communists, assisted by some social democrats who were pledged to co-operation (among these was Evzen Erban, the general secretary). The controlling organ was the Ustredni Rada Odboru (URO), the central council of the unions led by Zapotocky. The URO became almost part of the government and had the right to participate in government meetings and to send delegates to all bodies performing a social function. In fact, the URO was charged with drafting the decrees on nationalisation. Its power was made even greater because it was given control over the quasi-autonomous works council (zavodni rada) structures which represented workers in each plant or office.

Theoretically representing all workers, not only trade union members, these works councils participated in day to day decision making in the plants. In fact the ROH drew up the election slate and the works councils voted them in. The key element in the power of the works councils was not their ability to influence decision making but rather their control of the armed factory militias; forces set up to protect factories during the liberation which had retained their weapons and continued drilling under their new bosses. In the initial phase of reconstruction the trade unions were an important element in establishing domestic order and tranquillity under the close control of the Communists.

Gradually, as the movement in the international communist scene shifted away from a policy of co-operation with the bourgeois parties to one or more direct confrontations with them, the Czech Communist Party began to lose its appeal among the Czech electorate. This divergence was exacerbated by Stalin’s outright reversal of Czechoslovakia’s decision to attend a meeting scheduled to discuss participation in the Marshall Plan. The battle over Stalin’s refusal to allow communists to participate in Marshall Plan aid was the touch-paper for Cold War conflict in almost all the countries in Europe.

In Czechoslovakia, only the Czech Communist Party (KSČ), under direct Kremlin orders, refused to accept the Marshall Plan aid and its democratic program. The Communists were severely embarrassed by this and began to lose support. They first sought to gain lost ground by arranging a merger with the Social Democrats; a merger agreed by Fierlinger and his assistants Tymes and Vilim but rejected by others in the party. They ousted Fierlinger, supplanting him by Bohumil Lausman. The other parties united to resist. A propaganda barrage was let loose by the Communists who, through their control over the Ministry of the Interior, kept discovering “plots” against the regime; plots which tried to discredit the other parties. Trade union power was the means of takeover

The date for the new elections in 1948 was drawing nearer and the Communists were still losing control. They decided to use their most potent weapon to wrest control of the country from their opponents; to use their control over the unions to bring down the government. Following a ten day ultimatum on deciding new elections issued by the constitutional committee of the government, the Communists realised they had to act quickly. They used the discussions on the outstanding pay claim for civil servants as the instrument. The Social Democrat minister, Vaclav Majer, favoured a straight percentage increase; the unions demanded a weighted increase of an absolute sum which would favour lower paid workers.

When the minister won the point the Communists seized on the issue and Zapotocky announced that the URO had called a major conclave on industrial policy, for February 22, 1948, by the ROH and the works councils. The works council meeting was given lavish praise as the “parliament of working people” and the trade unions were hailed as “the greatest organised power in the land”. Companion meetings were arranged in all factories and workshops. Communist union organisers stirred up great enthusiasm for solidarity actions in defence of the workers’ “just demands”.

The other parties protested vehemently against the calling of the works council congress. The Communists had used their strong position in the Ministry of the Interior to order the national police (who were also organised into unions and works councils) to assist the works council meetings. The democratic parties ordered Nosek (the Communist minister of the interior) to rescind an order calling for the replacement of regional police officers by Communists. The prime minister, the Communist leader, Gottwald, tabled all motions and discussion on the issue and Nosek was diplomatically ill at the next cabinet meeting. When Peter Zenkl demanded that Gottwald give some answer on the police issue, Gottwald evaded an answer but brought up the details of another “plot” discovered by the police which implicated Zenkl’s party. The National Socialists resigned, as did the People’s Party and the Slovak Democrats. Only the Social Democrats and the two ministers without party affiliation, Jan Masaryk and General Ludvik Svoboda, decided to stay on.

This breakdown of the government occurred two days before the works council congress was scheduled to begin. By February 17, the party secretary in charge of the trade unions, Rudolf Slansky, had already put the factory militia at a state of readiness. When Slansky ordered that the workers be vigilant against a “reactionary coup” the militia and trade union security patrols (strazni hlidka) were placed on a 24 hour alert. The forces of the unions were turned into an effective alternative army run by the Communists, under the leadership of a general staff composed of regional commanders.

On the night of February 23, 1948, a convoy of trucks, escorted by the police, brought guns from the Zbrojovka factory in Brno to Prague where they were distributed to the trade union offices. On February 25, arms from other factories were distributed to 6,550 militiamen in key factories across the country as fortified operational bases. Meanwhile the Communists had used their power in the unions to bring the capital to a halt. On February 21 the ROH called a demonstration of over 100, 000 in Wenceslas Square which called for a change of government. The Communist print union then refused to supply newsprint for the non-Communist newspapers and Communist-led truckers refused to distribute non-Communist pamphlets. On February 24 the unions called for an impressive one hour general strike at noon, and the following day a massive rally was again held to celebrate the victory of the Communist coup in Czechoslavakia.

The final capitulation of the Social Democrats under Fierlinger, who had regained power on February 24, marked the end of the Czech experiment in democracy. The Communists gained effective control over the country and took over all the cabinet offices. Zapotocky became vice-premier. In May, after elections, Gottwald became president and Zapotocky premier.

Without the trade unions the Czech coup would not have been possible. The Communist victory in Czechoslovakia caused a major upheaval in what was already a deteriorating situation among the former Allies and heightened the tensions which were leading to a full scale cold war in both the national as well as the trade union sense. What happened in Czechoslovakia was not the product of unique or especially Czech circumstances. The pattern of communist intervention in national affairs through the medium of trade unions after the war was the rule rather than the exception.

The control of the trade union movement was the lever for the transition from a government of national reconciliation to one firmly under communist control. However, as austerity continued, the workers began to unite to complain and to try and improve their situation.

The East German Strikes 1953

These pressures first manifested themselves on a large scale in the 1953 strikes East Germany. In 1952 the economic situation in East Germany was terrible. The occupying Soviet forces demanded the East Germans contribute to direct and indirect costs for the occupation of East Germany. This annual fee (about 11% of the national budget) was augmented by another 9% of the national budget paid to the Soviets for “reparations”. The Soviets insisted that East German industry be directed primarily towards heavy industries, as opposed to food and consumer goods. Electricity was rationed and the nights were dark as there was only very limited power in the evening.

Many East Germans left the country if they could and others were jailed in large numbers when they complained. Despite the high levels of poverty and deprivation the Soviets insisted that the ruling East German Communist Party (“SED”) introduce a new policy of higher taxes, longer work norms (by 10%) for the same pay, and higher prices for food and consumer goods. Social unrest grew and it wasn’t until the death of Stalin in March 1953 that Walter Ulbricht, then general secretary of the SED (known as the man who built the Berlin Wall), was summoned to Moscow by Georgi Malenkov and asked to reduce some of the harshest practices.

This was not enough to suppress the unrest in East Germany. On the 16th of June 1953 three hundred construction workers marched on their union headquarters, the Free German Trade Union Federation, and then the ministry demanding a reduction of the work quotas. They were soon joined by other workers who expanded their demands to include an end to austerity, and soon these demands included a demand for free elections and an end to SED domination. The East Germans didn’t know how to handle this growing protest of over 40,000 workers across the industrial centres of the country.

The Soviets did know what they wanted and 16 Soviet divisions with 20,000 soldiers as well as 8,000 East German police “Vopos” were sent in to put down the spreading demonstrations. The West German authorities reported that 513 people were killed, 106 were executed afterwards, 1,838 were injured and 5,100 were arrested. The protests were over. The East German protests set off similar discussions throughout the Comecon states where austerity was strictly enforced and a dearth of consumer goods was the norm.

A milestone in the demands for change in the Comecon nations was the reaction to the famous speech by to the 20th Party Congress on February 25, 1956 which denounced the cult of personality of Stalin, his purges and rule by fear; promising an improvement by removing the oppressive Stalinist policies. This speech promoted a wave of dialogue and discussion throughout Eastern Europe on how to build new local, national socialisms, which would not have to be put in the Soviet Procrustean bed.

Intellectuals and politicians began to believe that the Khrushchev speech was the opening of a dialogue of reform in the USSR. Prisoners began returning from the Gulag. The Khrushchev speech did not fundamentally change Soviet society, largely because the Politburo was still full of men whose careers were made by loyalty to Stalin. However, the effects of the speech were felt outside the USSR; it became a factor in the unrest in Poland and revolution in Hungary later in 1956.

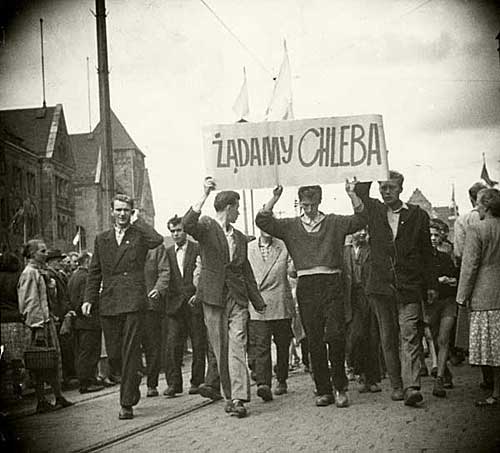

The Poznań 1956 uprising (Polish Revolution)

After the Khrushchev speech there was a spirit of reform growing in Eastern Europe. A particular focus of this new energy was Poland which had suffered under the imposed austerity programs insisted upon by the Soviets and where shortages of food were common in an economy which was a massive producer of agricultural produce.

Several leading cultural, academic, and opposition leaders formed the Klub Krzywego Kola (Skewed Wheel Club) in Warsaw to promote discussions on reform, distribution of consumer goods and, eventually, the independence of Poland. Theirs was largely an academic exercise but it motivated the working class to turn against their state-controlled trade union structures to demand better wages, working conditions, housing and a release from the labour work norms introduced and policed by the state.

Small strikes and demonstrations by the Polish workers began in several industrial areas but the largest began on 28 June 1956 at Poznan’s Cegielski Factories. Workers at this plant had suffered a loss of wages that month due to the changes in imposed work quotas. Their unions were of no assistance. This strike involved over 100,000 people.

The suppression of the Poznan Strike led to the arrest of 250 people; 196 of whom were workers. The Party put in Wladyslaw Gomulka to calm things down (the Polish October) but suppressed any public mention or reference to the Poznan Strike. It wasn’t until the birth of Solidarity and the Gdansk Agreement in 1980 that the full story of the Poznan Strike became public knowledge.

The Hungarian Revolution 1956

As the crises in Poland and some labour strikes in Czechoslovakia were becoming known across Eastern Europe a similar wave of protests began to sweep across Hungary. After the war, the Soviets occupied Hungary and exacted a heavy price on the Hungarian people for choosing the wrong side in the war. The Soviet Army took an immense amount of plunder back with them from Hungary and requisitioned huge amounts of grain, meat, vegetables and dairy products. They also imposed a schedule of reparations on the nation which exacted a heavy burden on the Hungarian state and its people.

The Soviets nationalised all industries and collectivised agriculture. They sold to Hungary at above world prices and bought its exports at well below world prices. The workers had no means of redress as their union structure was imposed on them so they began to form works councils in parallel with the official unions. As in Poland, the intellectuals and academics formed their own structure for identifying how to change the communist system in the light of Khrushchev’s speech.

The Petofi Circle was formed in April 1956 by Young Communists: it was named after Sander Petofi, the famous national poet who had fought for Hungarian freedom in 1848 against the Austrian Empire. Soon thousands were attending meetings of the Circle, and the articles that they wrote for their literary gazette began to circulate among workers and students. They promoted trade union democracy, workers participation and consultation of management with the union committee on wages and welfare.

When they reached the radio station the secret police, the AVO (Allamvedelmi Osztaly), agreed to let a delegation of the protestors into the building. Two hours later they had still not appeared. As the crowd moved towards the front doors, the AVO surged out with machineguns and started to fire on the demonstrators. The crowd continued to move forward and disarmed the policemen. They took their guns and began to fire at the radio station. The workers dispersed to their factories, the ones that made weapons, and brought in truckloads of guns and ammunition into the capital.

The Communist Party was unable to negotiate directly with the demonstrators. In an effort to appease them and buy time the Party appointed Imre Nagy (who had been fired earlier for ‘deviationism’) as head of state and Janos Kadar as First Secretary. Kadar had been a prominent labour dissident and a ‘Titoist’ who had been tortured and imprisoned. The Party thought appointing these two would calm things down.

The demonstrators had formed a Revolutionary Council of Workers and Students and issued leaflets demanding a general strike.

The general strike began on October 23; not only in Budapest but also in many of the key industrial areas where workers’ strength was large – Miskolc, Gyor, Szolnoc, Pecs, Debrecen. Throughout the country the protestors set up Revolutionary Councils. These demonstrators were well-armed and took over radio stations and newspapers to circulate their demands for freedom and independence. The peasants delivered food to the councils and workers set up mechanisms to run the public services. That same day the Soviets sent in troops but they were confronted by a heavily-armed militia force so did not make the progress they had hoped for.

The uprising ended on November 15 but scattered incidents happen for almost six more months. The unofficial total of people killed during the uprising is between 30,000 and 50,000 Hungarians and 7,000 Soviets. The wounded numbers are almost double that. There were over 100,000 who fled across the border. The Soviets were firmly back in control.

Eat minced Khrushchev!

Rebellion Inside the Soviet Union

While all of these developments were important, they were largely conducted in the satellite states. The full impact of the pressures for reform hit hardest when the spark of freedom was lit by the Russian people themselves, inside Russia; the unsung heroes of Bloody Sunday of June 2, 1962 in Novocherkassk.

In May 1962 Khrushchev and the Politburo decided to place Soviet nuclear missiles in Cuba to demonstrate to the Americans what it was like to have nuclear missiles on its borders. The leadership knew that this policy would have serious consequences and ordered the military-industrial complex to increase armaments production. They chose guns over butter. This dramatic shift of the national resources away from the satisfaction of consumer demand towards expanded military capability was a watershed in the development of the USSR.

The country had to tighten its belt again. The relative improvement of people’s material standard of living achieved in 1955-60 was brought to a halt. A period of unrest began. In early 1962 in the city of Aleksandrov the authorities opened fire on a crowd of protesters. This marked the beginning of a series of clashes between the people and the state over food and prices; the people’s trust in the authorities had been unfounded.

On 1 June 1962 a price rise for meat, butter and eggs was announced. As usual the ‘necessity of important economic reforms’ was advanced as an argument for this attack on ordinary people’s basic standards of living:

“Everyone must grasp that if we don’t implement measures today such as an increase in the retail price of meat, tomorrow we will see a shortage of these products and there will be queues for meat,” said Khrushchev, describing the essence of the reforms.

Actually meat had already disappeared from the shelves in small towns and villages. People there had to purchase meat and other foodstuffs in the cities, or at private markets. At markets, however, the prices depended on those in the public sector and they shot up after Khrushchev’s announcement, thus making the supply situation unbearable.

The economic crisis of 1960-62 had created an explosive situation. The price reforms sent shock-waves through the entire country. Indignant workers held discussions to work out what was happening, but in the end they kept working all the same. In Novocherkassk it was different.

![Image [1960s Soviet propaganda poster: “We will come to victory of Communist Work”]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/We-will-come-to-victory-of-Communist-Work.jpg)

The situation was made worse by the arrogant attitude of the management who ordered the workers to fall in line with the policy. Large groups of workers formed as a unit and a strike for food was prepared. The metalworkers’ union put up signs ‘Give us meat and butter!’ and ‘We need flats to live in!’ The slogan ‘Eat minced Khrushchev!’ became very popular. The factory siren sounded bringing in more workers from the nearby workers’ suburb. They held a series of mass meetings.

That night, when the mass-meeting was over, tanks arrived. Workers began fighting their own Soviet Army and ‘blinded’ the tanks by covering up their vision slits. In the course of this battle, a tank crashed into a pylon, knocking it over and tearing down a power-line. The tank rolled into a trench and was unable to get out. That same night the KGB carried out its first series of arrests, taking into custody many of the speakers at the rally.

On the morning of 2 June a demonstration of between 10,000 and 30,000 participants began in front of the electric locomotive factory and set off towards the city centre. People carried placards with slogans calling for the maintenance of social justice; there were also portraits of Lenin. At the front were Pioneers (members of the Party children’s organization). When the demonstrators approached the bridge over the river Techa separating the workers’ suburb from the rest of Novocherkassk, they found tanks on the road ahead of them. The crowd of thousands began to chant: “Make Way for the Working Class!” The tanks did not move, nor did their crews give any sign of life, and the workers passed between them and continued on their way.

Finally the crowd reached the buildings of the city council and began demanding that the administrators come out. The square was full of people, old and young. The administration had fled through the back door. At that point in time soldiers armed with automatic weapons were brought in. They forced back the crowd and cleared the city council building of demonstrators. The bulk of demonstrators then headed for the police headquarters and began demanding that those arrested by the KGB be set free; nobody was released from the cells. Then the assembled demonstrators stormed the building.

Suddenly there were sharp reports of machine gun fire. The soldiers had opened fire on the people near the police station. The machine-gunners stationed on the rooftops around the perimeter of the square were clearly given the order to open fire. There were bodies everywhere, including a large number of children. However, the people were not to be intimidated so quickly. They began coming back to the square almost straight after the massacre, but were met by a terrible sight. The square was awash with blood, and the trampled white sun-hats of the children.

The workers weren’t intimidated. The majority of factories in the town stopped work, the streets filled with people. Cars with workers drove up from all directions. The workers filled the streets in a massive demonstration, even though armed soldiers could be seen in the distance. There was a sea of people on the square in front of the city council building; almost twenty thousand workers and their families. The tanks there tried to move off the square, but people wouldn’t let them. “Tell Khrushchev! Tell Khrushchev!” the crowd chanted, and then: “Let him see this! Let him see this!”

Although the revolt was hushed up and the trials not reported the Procurator-General’s report makes it clear that the top levels of the Soviet state were involved. The only hero was General Matvey Shaposhnikov, who was there from the beginning but had been relieved of his command for refusing to allow his men to shoot at the workers.

Late on 2 June internal troops were brought from Rostov-on-Don and all were given weapons and ammunition, and by 10 o’clock all divisions of these troops were in a state of battle-readiness. ”The authorities admitted to the deaths of 22 workers and the wounding of 39 more.” This was a gross understatement according to witnesses. About sixteen children were murdered and many more were hurt or arrested.

![Image [Gen. Matvey Shaposhnikov][colorized photo]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/matvey-shaposhnikov-soviet-military-commander-lieutenant-general-ww2-1945-hero-of-the-soviet-union-novocherkassk-tragedy2.jpg)

The vulnerability of the state to massed workers’ protests was an inspiration to the working people in Poland, East Germany, Czechoslovakia and Hungary. It was the spark that set organisations like Solidarnosc in Poland in motion. The heroes of Novocherkassk opened the first domestic crack in the wall of oppression.

The invasion will take place even if it leads to a third world war.

-Soviet Defense Minister Andrei Grechko

The Prague Spring

The efforts by reformers in East Germany, Poland, Hungary and Russia to reduce the burden of austerity was not unknown to the political activists in Czechoslovakia. Before the Second World War the Czech economy was one of the most important in Europe. It was an industrial centre with a high level of industrialisation. It was damaged during the war but emerged relatively well-equipped to continue its economic and technological expansion. However, the political demands of the KSC and its Soviet planners to introduce a high level of centralised planning based on the production of capital goods meant that the Czech standard of living began to decline sharply and the economy stagnated. Food and consumer goods both difficult to obtain and very expensive.

![Image Prague residents attempted to stop a Soviet tank in 1968. [Credit Libor Hajsky / AFP]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/Prague-residents-attempted-to-stop-a-Soviet-tank-in-1968.-Credit-Libor-HajskyAgence-France-Presse.jpg)

An economic crisis began to hit the economy as investment in industry and collectivisation produced a shortage of consumer goods and caused inflation to soar to 28 percent. To make things even worse, at the beginning of 1953 the regime hiked the prices of basic commodities and looked at increasing production targets. Gottwald’s death did not stop the dissent, especially on the shop floor. The new party boss Antonín Novotný decided that he could deal with the growing crisis by making the workers pay. The regime pushed through a currency reform that severely lowered workers’ livings standards—savings were devalued by 50:1, wages by 5:1. Just two months into the job, Novotný had terribly overplayed his hand. The unions retaliated.

The Vladimir Illych Lenin Works in Plzeň, the old Škoda plant, and its Metalworkers’ Union rose in revolt against the new party bosses in March 1953. Workers walked off their shifts and marched on the town hall. They were joined by workers from nearby enterprises and by students. The demonstration swelled to 20,000. Party buildings were burnt; barricades were built; the unionists controlled the town. In desperation, the Novotny Government brought the full force of the state to bear on Plzeň. The “People’s Militia”, the Czechoslovakian People’s Army and secret police brutally suppressed the demonstrators and won control back of Plzeň.

There was a growing pressure in the country for reform, including within the KSC where a strong reform groups was gradually moving into posts with authority. A faction began to form within the bureaucracy that argued for the introduction of market forces into Czechoslovakian state capitalism, similar to those in Tito’s Yugoslavia, in order to kick-start growth. Novotny refused to listen to them. The Czech economist Ota Šik began developing a programme of reforms, which were reluctantly accepted by Novotný in 1967. The reforms aimed to introduce internal competition between Czechoslovak firms in order to force the most inefficient to go to the wall. It was hoped that the shock of competition would rebalance the economy, reallocating labour and investment from the old export-orientated industries. Šik called this the New Economic Model and won the half-hearted support of Novotny.

The New Economic Model suggested the re-introduction of pre-Communist features, like the removal of price and wage controls. Factory managers and bureaucrats were to be given greater freedom in decision-making, so they could respond to resource availability and the needs of the market. There was a move by plant-level works councils to ignore the strictures on industrial relations imposed by the ROH and to unite the Czech and Slovak unionists into, effectively, a parallel structure. Antonin Zapatocky, a communist pre-war labour leader who had been imprisoned for six years during the war, had become the chairman of ROH in June 1947. Evsen Erban, a left-wing Social Democrat, became the general secretary of ROH. In the leading body of ROH, the Central Trade Union Council (ÚRO), there were 94 communists, 18 Social Democrats, 6 National Socialists and 2 from the Peoples Party. It wasn’t entirely a KSC-run body.

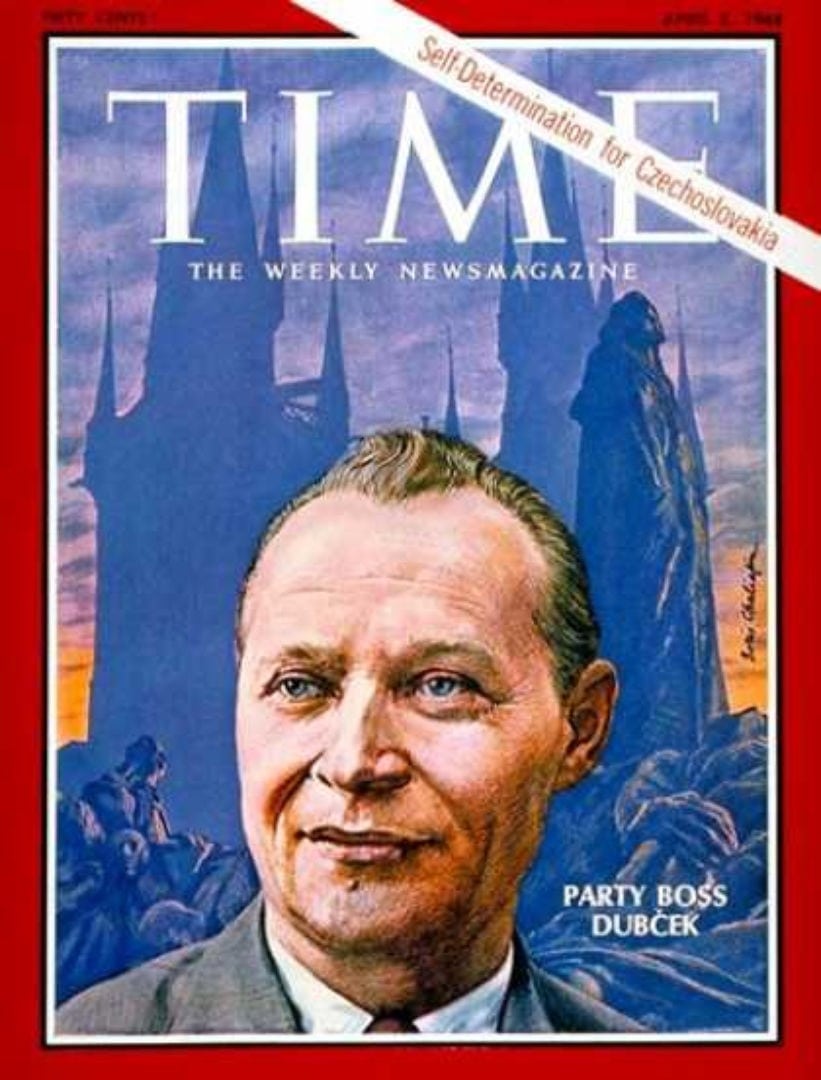

Novotny fell from power and on 5 January 1968, Alexandr Dubcek – a reformer – took over as leader of the Communist Party (KSC). The unionists and reformists inside the KSC pushed for greater reform and were rewarded by the publication of the Action Plan in the Spring of 1968. This plan called for the Czechs following their own form of socialism – “socialism with a human face” – instead of blindly following the Soviet Union’s model. It would be fundamentally democratic, tolerant of debate and different opinions; individual rights and freedoms, such as freedom of speech and the ability to travel abroad, would be protected by law.

In March 1968 the ROH was realigned to fit this program. Hardline Stalinists unionists were removed from their positions in ÚRO. Unions began to revise their rulebooks and procedures. In September 1968 ÚRO reaffirmed that the process of internal reforms and adoptions of new statues in the affiliated unions would continue. Between November 1968 and January 1969 some unions (like the Metal Workers’ Union) threatened to launch strikes if the pro-reform leaders weren’t reinstated to their positions in the Communist Party.

Not only had they supported removal of Antonin Novotny from his post as Communist Party leader, but Smrkovský’s public announcement (“What Lies Ahead”) at the end of January 1968 demonstrated the real impact of Alexander Dubchek’s election as First Secretary. Smrkovský was designated chairman of the National Assembly in April 1968, and became (together with Dubchek) one of the most popular politicians of the era. He was in favour of democratic reforms but maintained communist ideology, and continued to support the leading role of the KSC in the state.

For four months (the Prague Spring), there was relative freedom in Czechoslovakia. But then the revolution began to press towards programs that Brezhnev and his colleagues could not accept; including the Czech withdrawal from the Warsaw Pact. Dubcek announced that he was still committed to democratic communism, but other, non-communist, political parties revived and moved to take power from the KSC. Although there had not been Soviet troops stationed inside Czechoslovakia, the Warsaw Pact began manoeuvres on its borders. Time was running out for Czech democratic evolution.

A timeline of the events in Czechoslovakia illustrates the descent into repression by the Soviets. A recently declassified study by the CIA “Czechoslovakia: The Problems of Soviet Control” describes, in detail, the end of “socialism with a human face” and the fate of Dubcek. [Download full report]

A Chronology Of Events Leading To The 1968 Invasion [ii]

Jan. 5, 1968: Alexander Dubcek replaces Antonin Novotny as Party leader and declares his intention to press ahead with extensive reforms. Novotny was criticized by party liberals and intellectuals for his government’s poor economic performance and his anti-Slovak prejudice. Dubcek is seen as the perfect compromise candidate, acceptable to both the orthodox party members and reform wing.

February: Communist Party leadership approves enlargement of the economic reform program started in 1967. Journalists, students, and writers call for the repeal of the 1966 Press censorship law.

March: Public rallies held in Prague and other cities and towns in support of reform policies voice growing criticism of Novotny’s presidency.

March 22: Novotny resigns as president, after facing pressure by party liberals.

March 30: General Ludvik Svoboda is elected president of Czechoslovakia. Svoboda was a war hero who had also served in the Czechoslovak legion at the start of the Russian Civil War in 1918.

April 5: Action Program of the Communist Party is published, part of the effort to provide “socialism with a human face.” It calls for the “democratization” of the political and economic system. The document refers to a “unique experiment in democratic communism.” The Communist Party would now have to compete with other parties in elections. Document envisages a gradual reform of the political system over a 10-year period.

April 18: A new government is formed under Dubcek ally and reformer Oldrich Cernik. Liberalization process goes full swing. Press continues to become more outspoken in support of freedoms.

May 1: May Day celebrations show huge support for the new cause.

May 4-5: Czechoslovak leaders visit Moscow: Soviet leadership expresses dissatisfaction with developments in Czechoslovakia.

May 29: A number of high-ranking Soviet military officials visit Czechoslovakia to lay the groundwork for Soviet military exercises.

June 26: Censorship is officially abolished.

June 27: Two Thousand Words manifesto signed by reformers, including some Central Committee members, is published in Literarny Listy and other publications. It calls for “democratization,” the re-establishment of the Social Democratic Party, and the setting up of citizens’ committees. The manifesto is a more radical alternative to the Communist Party’s April Action Program The political leadership (including Dubcek) rejects the manifesto.

July 4: Beginning of Soviet-led military exercizes in Sumava, aimed at strengthening the hand of anti-reformist forces in Czechoslovakia.

July 15: Representatives of the Communist parties of the Soviet Union, Hungary, Poland, East Germany and Bulgaria meet in Warsaw. They send a strongly worded diplomatic note warning the new Czechoslovak leaders that “the situation in Czechoslovakia jeopardizes the common vital interests of other socialist countries.”

July 29-Aug. 1: Negotiations are held between the presidiums of the Czechoslovak and Soviet communist parties in Cierna-nad-Tisou. Dubcek argues that reforms did not endanger the role of the party but built public support. The Soviets do not accept these arguments and sharply criticize the Czechoslovak moves. Threats of invasion are made.

July 31: East Germany, Poland, Hungary and Soviet Union announce that they will hold military exercises near the Czechoslovak border.

Aug. 3: A Warsaw Pact meeting (without Romania) is held in Bratislava. The meeting brings about a seeming reconciliation between the Warsaw Pact leaders and the Czechoslovak leadership. Here for the first time, the so-called Brezhnev doctrine of limited sovereigny is announced. Soviet leader Leonid Brezhnev receives a handwritten letter from five members of the Czechoslovak Presidium who warn that the socialist order is under threat. They request military intervention.

Aug. 18: The Kremlin decides on the invasion of Czechoslovakia. The commander of Soviet Central Forces, General Aleksandr Mayorov, relates how Soviet Defense Minister Andrei Grechko stated to the assembled Soviet Politburo and military leaders: “the invasion will take place even if it leads to a third world war.”

Aug. 20: Czechoslovakia is invaded by an estimated 500,000 troops from the armies of five Warsaw pact countries (Soviet Union, Poland, Hungary, Bulgaria, and East Germany) overnight into Aug. 21.

Aug. 21, Shortly after 0100: State Radio announces invasion by troops from five Warsaw Pact countries. It says the invasion took place without the knowledge of the Czechoslovak authorities. “The Presidium calls upon all citizens of the Republic to keep the peace and not resist the advancing armies, because the defense of our borders is now impossible.” The army is given orders to remain in its barracks and not to offer resistance.

Aug. 21, 0300: Czechoslovak Premier Oldrich Cernik, Dubcek, Jozef Smrkovsky and Frantisek Kriegel — the four leading reformers in Czechoslovak leadership — are arrested in the Communist Party’s Presidium building by Soviet airborne troops.

Occupation governments distribute leaflets saying the troops were sent in “to come to the aid of the working class and all the people of Czechoslovak to defend socialist gains.”

Aug. 21, 0530: Tass says that Czechoslovak Party and government officials requested urgent assistance from the Soviet Union and other fraternal countries.

Aug. 21, 0600: Svoboda makes radio address calling for calm and for people to go to work as normal.

Aug. 21, 0800: Crowds and Soviet troops confront one another on Old Town Square and Wenceslas Square. Tanks appear at the Museum and start firing at nearby buildings and the National museum.

Dubcek and other party leaders are flown to Moscow and are compelled to participate in talks with Moscow leadership. They sign a document in which they renounce parts of the reform program and agree to the presence of Soviet troops in Czechoslovakia.

Invasion draws condemnation from Western powers as well as communist and socialist parties in the West. U.S. President Lyndon B. Johnson calls on Soviets to withdraw from Czechoslovakia.

Aug. 23: Svoboda flies to Moscow with large delegation of Czechoslovak Communist leaders to negotiate a solution.

Aug. 25: Czechoslovak leaders sign so-called Moscow protocol which renounces parts of the reform program and agrees to the presence of Soviet troops in Czechoslovakia.

Aug. 27: Svoboda returns to Prague with Dubcek, Cernik.

Aug. 31: 14th Party Congress declared invalid, as required by the Moscow protocol. Censorship is reintroduced in the country.

Oct. 28: Czechoslovakia becomes a federal republic, the only major objective of the reform process that came to fruition.

Jan 16, 1969: Czechoslovak student Jan Palach sets himself afire in protest.

April 17, 1969: Dubcek removed as party first secretary, after disturbances that follow Czechoslovak hockey team’s victory over a Soviet team in Stockholm. Dubcek replaced by Gustav Husak with full support of the Soviet Union.

The Prague Spring was over.

The last words should be that of the Czech literary genius, Karel Čapek in Válka s mloky (“The War of the Newts”) where he asks “And did you groan?”

“‘Could you be kind enough to tell me,’ enquired our dear companion eagerly, ‘what there is new in mother Prague with her hundred towers?’

‘She’s growing bigger, my friend,’ I answered, pleased by his interest, and in a few words I outlined to him the flowering of our golden metropolis.

‘What pleasant news you bring me,’ said the Newt with unconcealed satisfaction. ‘Do they still hang on the Bridge Tower the heads of Czech noblemen who have been beheaded?’

‘Not now for a long time,’ I said to him, rather (I confess) astonished by his question.

‘Forsooth, that’s a pity,’ reflected the engaging Newt. ‘It was a fine historical memorial. May lamentations rise to God that so many excellent monuments perished in the Thirty Years War! If I am not mistaken, the Czech land was then turned into a desert, soaked with blood and tears. What good fortune it was then that the negative genitive did not disappear. In this booklet it states that it is on the point of extinction. I felt very distressed about it, sir.’

‘Then you have been captivated by our history,’ I exclaimed joyfully.

‘Certainly, sir,’ responded the Newt. ‘Especially by the battle of the White Mountain and the Three Hundred Years suppression. I have read very much about them in this book. You certainly must be very proud of your Three Hundred Years suppression. It was a great time, sir.’

‘Yes, a tragic time,’ I affirmed. ‘A period of suppression and grief.’

‘And did you groan?’ inquired our friend with eager interest.

‘We did, suffering unspeakably under the yoke of brutal oppressors.’

‘I am glad,’ sighed the Newt with relief. ‘In my booklet it is just like this. I am very pleased that it is true. It is an excellent book, sir, better than the Geometry for Senior Classes in Secondary Schools. I should like to stand myself on the sacred spot where the Czech noblemen were executed, as well as on the other famous places of cruel injustice.’” [iii]

Dr. Gary K. Busch, for Lima Charlie News

[Edited by Anthony A. LoPresti][Main Photo: Josef Koudelka][Read Part 2 here]

Dr. Busch has had a varied career-as an international trades unionist, an academic, a businessman and a political intelligence consultant. He was a professor and Head of Department at the University of Hawaii and has been a visiting professor at several universities. He was the head of research in international affairs for a major U.S. trade union and Assistant General Secretary of an international union federation. His articles have appeared in the Economist Intelligence Unit, Wall Street Journal, WPROST, Pravda and several other news journals. He is the editor and publisher of the web-based news journal of international relations www.ocnus.net.

Sources

[i] For detailed studies of the political role of international labour and the Cold War Conflict, see:

- Busch, G., “Political Currents in the International Trade Union Movement” vol. 1 and 2, Economist Intelligence Unit, Special Report No. 75, London 1980

- Busch, G. The Political Role of International Trade Unions, Macmillan 1983

- Busch, G. Free for All: The Post-Soviet Transition of Russia, Virtualbookworm 2010

[ii] Matthew Frost, RFE/RL 28/8/1998

[iii] Capek, Karel. War with the Newts, Allen & Unwin 1937

[Subscribe to our newsletter for free and be the first to get Lima Charlie World updates delivered right to your inbox.]

Lima Charlie provides global news, featuring insight & analysis by military veterans, intelligence professionals and foreign policy experts Worldwide.

For up-to-date news, please follow us on twitter at @LimaCharlieNews

Part 2:

In case you missed it:

![Image Workers Unite! Soviet Influence, Eastern Europe and Reflections on the Prague Spring [Lima Charlie News][Photo: Josef Koudelka]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/Workers-Unite-Soviet-Influence-Eastern-Europe-and-Reflections-on-the-Prague-Spring.jpg)

![Image GailForce to Space Force: 'Make it so' - the Space Force debate continues [Lima Charlie News]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/Space-Force-01-480x384.png)

![Image War in Eastern Ukraine and the New Heroes of ‘Novorossiya’ (New Russia) [Lima Charlie News]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/Donbass-MAIN-01-480x384.png)

![Image Drop in oil prices may trigger unintended consequences [Lima Charlie News]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/main_900-480x384.jpg)

![Image GailForce to Space Force: 'Make it so' - the Space Force debate continues [Lima Charlie News]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/Space-Force-01-150x100.png)

![Image War in Eastern Ukraine and the New Heroes of ‘Novorossiya’ (New Russia) [Lima Charlie News]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/Donbass-MAIN-01-150x100.png)