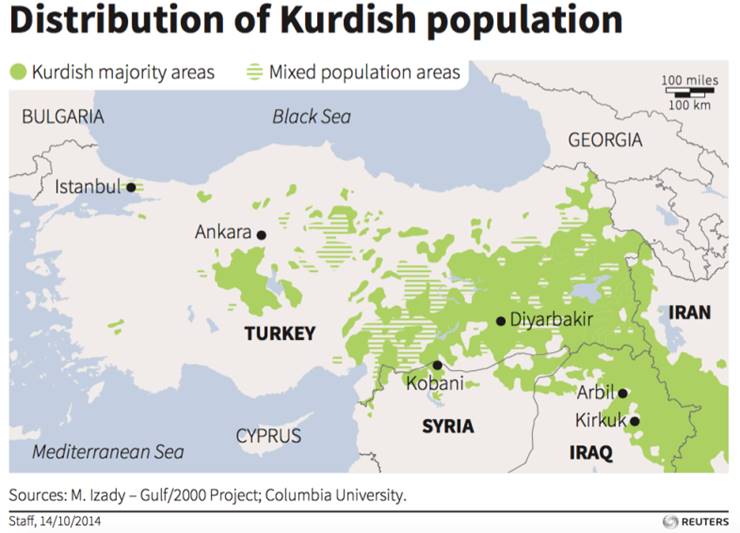

Today about 30 million Kurds occupy a region that includes enclaves within Iraq, Iran, Syria and Turkey. The role and status of these Kurdish groups shape the conflicts which continue in these nations, while Kurd forces have become America’s surrogate army in the region. Whether the Kurds will ever have their own independent state is a question that requires an examination of the history of Kurdish autonomy. Part 1 of this series examines the Kurds in Iran and Iraq. Part 2 examines the Kurds in Turkey and Syria.

Two weeks ago, in a non-binding referendum, Iraqi Kurdistan voted for its autonomy. This provoked a hostile reaction from the nations of the region. The Turks, Iranians, and the Iraqis have all turned against the prospect of a flourishing independent Kurdistan and may use the opportunity to put further pressure on the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG). It seems as though an independent state called Kurdistan is not likely to feature on the political horizon very soon.

Compounding the situation is the question of U.S. support. Peshmerga Kurd forces and the People’s Protection Units (YPG), a mostly Kurdish militia, have become America’s surrogate army in the region. For some inexplicable reason, President Donald Trump’s policy has been to stop further arms supplies to the YPG and the Syrian Democratic Forces (‘SDF’). At the same time the victors of the liberation of Mosul, Iraq – largely the Peshmerga – are now being threatened by the Shia militias which are, effectively, the Iraqi arm of Iran’s Revolutionary Guard (Pasdaran).

Nevertheless, the U.S. has refused to support the Kurds in Iraq and is busy withdrawing its support from the YPG and SDF. This bizarre line of thought risks losing everything that has been fought for, for almost sixteen years.

The Delicate Position of the Kurds After the September Referendum

Kurdish political destinies have depended on their relations with the governments within whose national borders they have been consigned to exist. In recent years, the relations with these governments has never been anything other than complex and conflicted.

Historically, the Kurdish national territory has been split among four countries and represents the largest ethnic group in the Middle East without a nation state of its own. The Kurdish demand for a nation state has been resisted over many centuries and was ignored by the signatories to the Sykes-Picot Agreement which divided up the Ottoman Empire between French and UK control. This briefly changed at the Paris Peace Conference of 1919-1920, where the Great Powers outlined a procedure for the Kurds to establish a separate state. An autonomous area was carved out for the Kurds east of the Euphrates, south of Armenia and north of the Turkish frontier with Syria.

The Kurds prepared for a gradual autonomy and later self-rule, but were overtaken by the revolution which rose up when Kemal Ataturk installed his new, secular, Turkish state in 1923. The Kurds lost their autonomy and hope of independence and even their identity. The Treaty of Lausanne (1923) would replace the Sykes-Picot Agreement and the Kurds’ demands were no longer recognised.

The eternal problem for the Kurds has been that they are disunited. Kurds don’t need extra enemies; they are happy to provide their own. There have been two major Kurdish Civil Wars, and the fighting between the Barzani and Talabani factions has never ceased in Iraq.

The recent death on October 3, 2017 of Jalal Talabani, Iraq’s former President and leader of the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (‘PUK’), may make a slight change to the relations between the two factions of Kurds. Yet progress on any major scale is unlikely. The wars between Sunni and Shia Kurds in Iran also make no contributions towards intra-Kurd co-operation.

To truly understand the lack of unity that has stood in the way of progress towards an independent Kurdistan, the roots of an ancient antagonism among the Kurds must be explored.

The Kurds In Iran

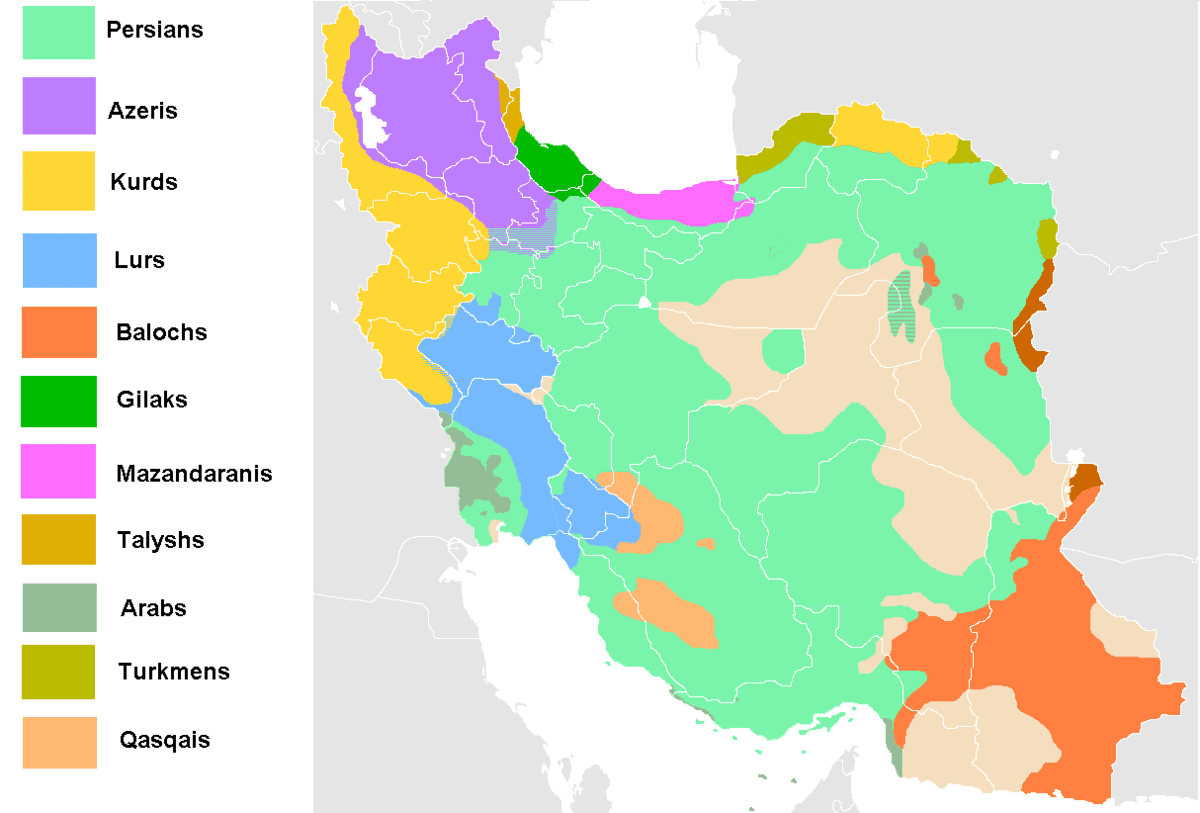

The Kurds in Iran inhabit mostly north-western territories known as Iranian Kurdistan, but also the north-eastern region of Khorasan, and constitute approximately 10% of Iran’s overall population.

The Kurds have been in Iran for many centuries and have always been considered a non-assimilated ethnic group. Periodically they attempted to rebel against the central government in Tehran, but their efforts were largely unsuccessful. Their relations with the Iranians were tempered by the political struggles of Kurds within the greater four-country area of Kurdistan.

The majority of the Iranian Kurds are Sunni Muslims, although there is a large number of Shia Kurds. The Iranian governments have always opposed Kurdish nationalism but have been far less harsh in their repression of the Kurds than other countries. This is a result of the ethno-linguistic ties between the Kurds and the Persians who consider the Kurds as emerging from similar Persian ethnic roots. As a result, there are many Kurds in Iran who have considered themselves Iranians and are hostile to the notion of an independent Kurdish state. This is especially true for the Shia Kurds who have been unmoved by the lure of Kurdish autonomy. This is less true for the Sunni Kurds whose point of view was shaped by the events in the wider, mainly Sunni, Kurdistan periphery.

The first concerted effort of the Kurds in Iran to assert their aspirations for autonomy took place in the Simko Shikak revolt of 1918-1922. Simko Shekak was a Kurdish chief (from the Turcophone Shekel tribe) who looted and plundered across the Kurdish areas in Iran. It was more of a search for hegemony and plunder than a search for political autonomy. He attacked Alevi Kurds and massacred large numbers of Assyrians. He was ruthless in attacking Kurds as well as the government forces. Nonetheless, modern Kurds refer to him as an important figure in the Kurdish nationalist movement and a hero in the struggle for independence. When government troops attacked Simko half of his troops defected to the tribe’s former leader and Simko Shekak fled into Iraq.

Although Persia was neutral during the Second World War it was, nonetheless, invaded by the Anglo-Soviet forces comprised of Soviet, British and other Commonwealth armed forces. The invasion lasted from 25 August to 17 September 1941, and was codenamed Operation Countenance. The purpose was to secure Iranian oil fields and ensure Allied supply lines for the Soviets fighting against Axis forces on the Eastern Front, and to prevent their falling to the Germans and the Vichy French. Though Iran was officially neutral, according to the Allies, its monarch Reza Shah was friendly toward the Axis powers and was deposed during the subsequent occupation to be replaced with his young son Mohammad Reza Pahlavi.

In the confusion and anarchy resulting from the Anglo-Soviet invasion, another Kurdish chief embarked on a revolt against the state. The Hama Rashid Revolt led by Muhammed Rashid lasted from late 1941 until April 1942, re-erupting in 1944, before Rashid’s defeat by the government. While unsuccessful, it spawned the growth of a Kurdish nationalist political movement which emerged in the immediate post-war Iran 1945-1946.

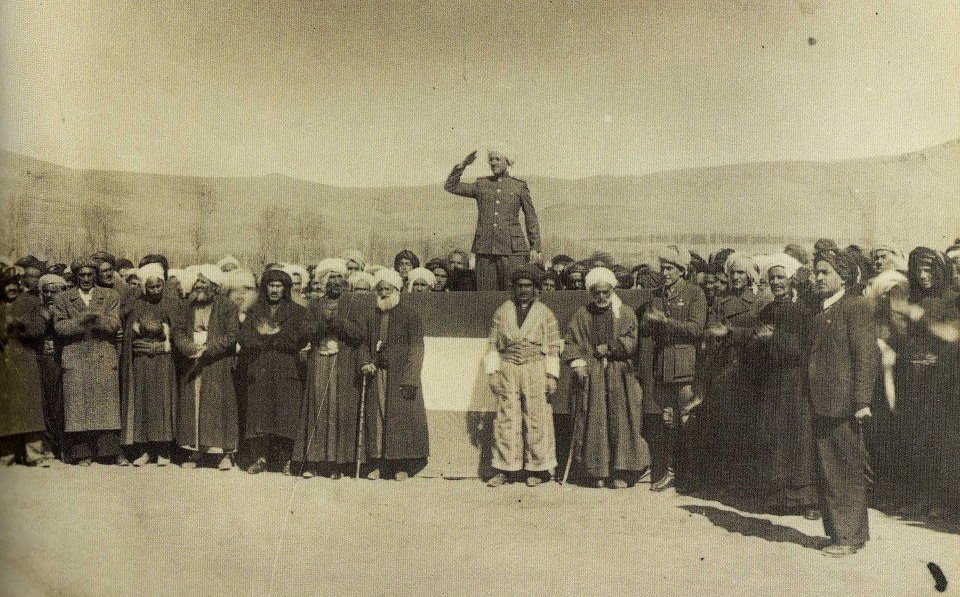

With the occupation of Iran by British and Soviet troops the key supply line from the Levant to the Soviets was created and expanded. A consequence of the Soviet presence was the takeover of the administration of the Kurdish areas of Iran. The Soviets established the Tudeh (the Iranian Communist Party), the first acts of which were to pit local farmers in an uprising against their landlords. In addition, Soviet authorities announced the creation of an independent Kurdish People’s Republic and a People’s Republic of Azerbaijan under Soviet control.

Iranian Kurds were given autonomy. This Soviet Republic of Mahabad, as it was called, was led by the Kurdish Movement (Komeley Jiyanewey Kurd) under the leadership of Qazi Muhammad and his Democratic Party of Iranian Kurdistan (‘KDPI’). Some Kurds were attracted by the promise of autonomy, but most Iranian Kurds eschewed contact with it. The Republic of Mahabad lasted less than a year. When Soviet forces withdrew, the Iranian government marched in and removed the separatists.

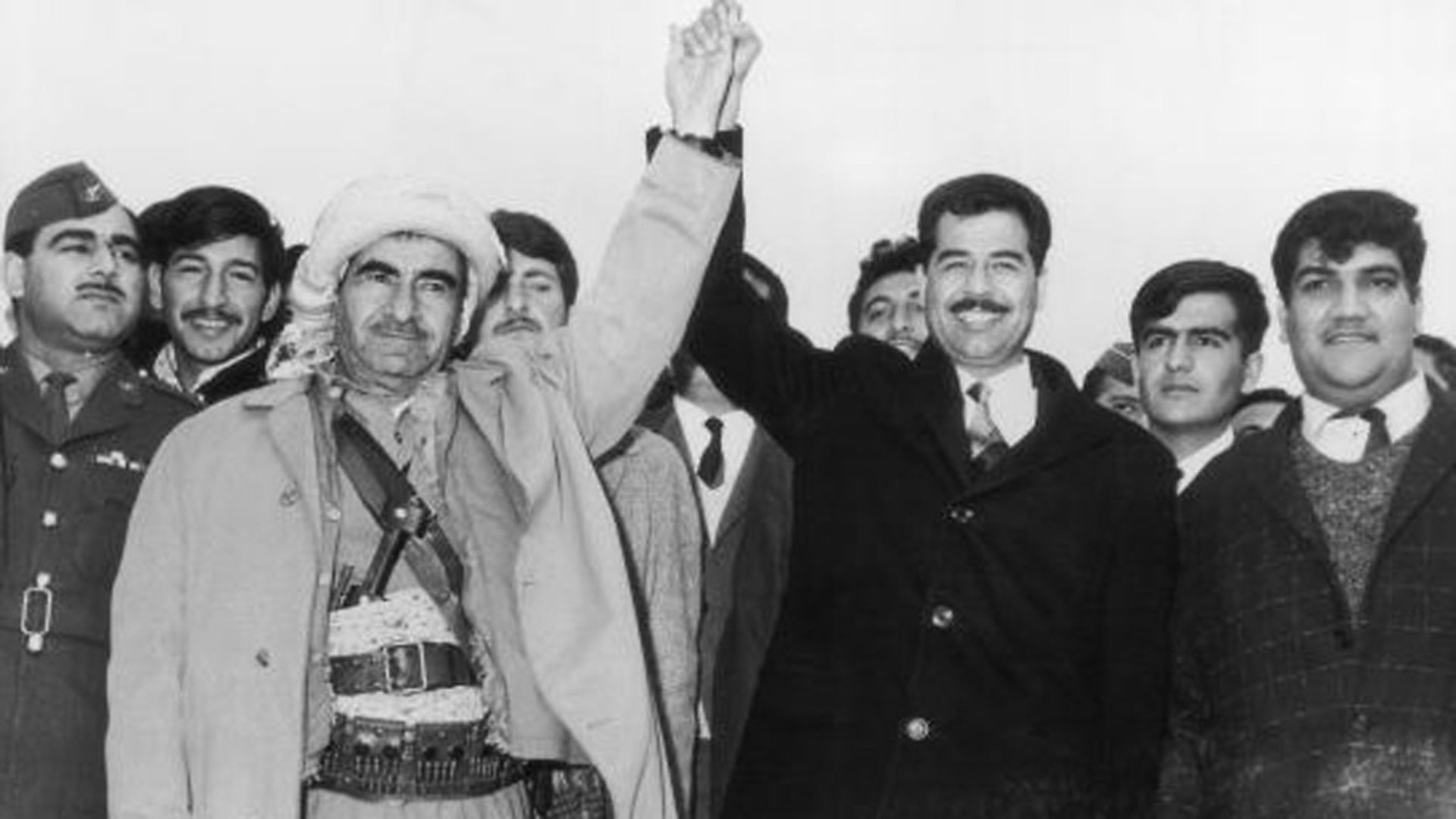

While the Soviets had occupied Mahabad they mobilised the Kurds on both sides of the border to fight against both the Iranian and Iraqi monarchies. Qazi Muhammad was joined in the Republic of Mahabad by Mustapha Barzani (‘Mulla Mustafa’), an Iraqi Kurdish leader and a head chief of the Iraqi Kurdish tribal elders, on the run from Iraq. The Soviets and Qazi demanded that Mulla Mustapha subsume his party into the KDPI and accept Soviet guidance. Barzani was not happy with this and maneuvered to maintain his effective autonomy. He was able to form the Kurdistan Democratic Party (‘PDK’ or ‘KDP’) among the Barzani tribes in the Kurdish area of Iraq in 1946, which he led from exile. This party called for autonomy for Iraqi Kurdistan. This process created a separate Kurdish movement in Iraq, separate and different than the movement in Iran.

Kurds were relatively neutral when the Iranian revolution of early 1979 ousted the Shah and installed Ayatollah Khomeini. They soon found that the ayatollahs had no tolerance for Kurdish participation in the new Islamic state; especially the Sunni Kurds. In May 1979 the Kurds were willing to support the new government but, as opposition groups in Iran (primarily the Arab, Baluchi, and Turkmen minorities) turned towards open rebellion against the new Iran theocracy, the Kurds (mainly Sunni Kurds) eventually joined in the struggle for autonomy from the new Iranian state.

Sunni Kurdish leftist politicians from the Mahabad Region formed guerrilla units against the Iranians. These insurgents from the KDPI and their allies in Tudeh, took over swathes of Kurdish-occupied territory. However, by the beginning of 1980 the Iran-Iraq War had begun and the Iranian Revolutionary Guard turned its strength against the KDPI and captured the rebel territory. Some forces kept fighting until 1983. About 10,000 people were killed in the course of the Kurdish rebellion, with 1,200 of them being Kurdish political prisoners, brutally executed in the last phases of the rebellion, mostly by the Shia government in Iran.[i]

The PDK, that had continued to grow in Iran, had supported the 1979 Revolution against the Shah. When, however, the new theocratic Iranian Government turned against the Kurds, the Kurds expanded their ties with the Left factions in Iran and attempted their own revolution against Khomeini. This lasted a little over eighteen months before the Revolutionary Guards overwhelmed them and the party and its allies were banned with many fleeing into exile. The party continued in Iran, but primarily underground.

In July 1989 the KDPI rejoined the armed struggle with the Iranians when the leader of the party, Abdul Rahman Qassemlou was assassinated by Iranian government agents. Battles were engaged with the KDPI forces. In the 1990s, armed clashes continued between KDPI and government forces, including bombing attacks against Iranian Kurds, both in western Iran and inside Iraqi territory. In an effort to negotiate a peace the Iranians agreed to a discussion with the KDPI. On 18 September 1992, the Iranian Kurdish leader, Sadik Sharafkindi and three others were assassinated in a restaurant in Berlin, where Sharafkindi had gone to hold secret autonomy talks with Iranian government representatives. That ended peace talks. The KDPI continues to be subject to attacks by the Iranian regime.

The fundamental Kurdish problem is that their parties and movements keep splitting and opposing their former allies. The Iranian Kurds have not been able to form any lasting alliances with other Kurdish nationalist parties or parties of the Left with whom they maintain sometimes cordial relations. This includes a split between Shia and Sunni Kurds who find unity a chimera.

The Kurds In Iraq

A major concern of the international community has been the fate of the Kurds of Iraq, especially as related to their role in the war of the international coalition against Saddam Hussein. Moreover, a large part of the Iraqi oil industry is located in Kirkuk, Mosul and Erbil – within what is called the Autonomous Kurdish State. Oil was discovered early there and a substantial oil industry developed in the region.

The fate of the Kurds in Iraq has been bound closely with the struggle for power inside the country, first against the monarchy and later against the Baathists. The role of the Kurds in the wider struggle for power in Iraq was not only because of the territorial claims of the Kurds on “Kurdistan”, but also the important role played by the Kurdish labour movement in the creation of a coherent pressure from the left on the movements for social justice in Iraq. As those who were among the first to be employed in industry (the oil industry) the Kurds developed an industrial base as well as a political base.

While the Soviets had occupied Mahabad during the early 1940s, many Kurds were trained to participate in social and political movements in Iraq as well as Iran. When Mulla Mustafa organised the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP) in the Barzani-supervised areas of Iraqi Kurdistan, the Kurds played a national as well as a regional role. However, when the PDKI moved across the Iranian border to Kurdish-controlled Iraqi Kurdistan, many of the Kurdish leftist intellectuals and unionists began to take over control of the Iraqi KDP. In 1945, Ibrahim Ahmad took over the KDP leadership in Iraq and maintained a working relationship with the Iraqi Communist Party (‘ICP’) who were also strong in the Iraqi labour unions. In the late 1940s and early 1950s they fielded joint candidates in several constituencies.

The ICP campaigned directly against the aghas (tribal elders) and won the support of the workers in the cities of Erbil, Duhok, and Sulaymaniyah – while the KDP reassured the aghas that the ICP was ultimately under their control. By 1954 the KDP was advocating the replacement of the Iraqi monarchy with a popular democratic republic – much to the consternation of many of their tribal supporters.[ii]

The Iraqi Revolution

The Iraqi revolution of 1958 took place in several stages. The first revolution was triggered on Bastille Day (July 14, 1958) when the overthrow of the British-installed monarchy by Iraqi Free Officers touched off the most powerful demonstration of revolutionary ardour in the Near East. Armed and highly organized, the Iraqi underground labour unions, led by the Iraqi Communist Party (ICP), stood on the brink of seizing power. Within the ICP the leading role in the revolution was played by Kurdish workers in the oil fields and industries of Kirkuk and Mosul.

Within weeks, a peasant insurrection was sweeping across the agricultural plains of Iraq as peasants burned landlords’ estates, destroyed the account ledgers and seized the land. The ICP controlled the labour unions, peasant organizations, and the union of students. Mammoth rallies, some drawing over a million participants, were staged in Baghdad under ICP leadership. President Eisenhower responded to the revolutionary explosion by sending Marines to Lebanon and preparing for a possible invasion of Iraq. The Wall Street Journal (16 July 1958) candidly declared: “We are fighting for the oil fields of the Middle East.”

The 1958 revolution had an enormous impact throughout the Near East, not only on workers, but also on the Kurdish people. One measure of the revolutionary turmoil in Iraq was that the new constitution cited the Kurds as equal partners with Arabs in society (without of course recognizing the Kurds’ right to independence).

The Iraqi Communist Party was not only the most proletarian of the Communist parties in the Near East; from its inception it had a large number of members from national and ethnic minorities, including Jews. In the period from 1949 to 1955, every general secretary of the ICP was Kurdish, as was nearly one-third of its central committee.

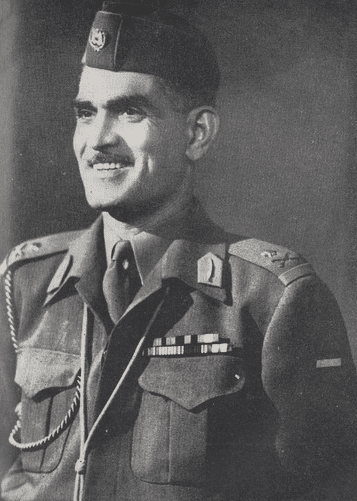

From the outset of the 1958 upsurge, the ICP (under tight Moscow guidance) threw its support behind the government headed by Brigadier Abd al-Karim Qassim, whom the Stalinists hailed as their “sole leader.” The high point of the revolution came in early 1959 when the ICP mobilized a quarter of a million people in Mosul, many of them armed, to suppress a coup by Nasserites and counter-revolutionary officers.

This triggered several days of street fighting in which Communist-led workers and soldiers mopped up the conspirators and their bourgeois backers, arresting many and hanging others from lampposts. Armed militants of the People’s Resistance Force (PRF), a popular militia that had been set up by Qassim in July 1958 and quickly taken over by the Communists, essentially took power in the city.

At this point, the ICP had more support among military officers than the Free Officers movement had when it took power on 14 July 1958. The commander of the air force was an ICP supporter, as were almost one-quarter of the pilots. A number of these military commanders demanded that the ICP leadership take power. Above all, the People’s Resistance Force, which had just demonstrated its power in Mosul, numbered, by a conservative estimate, 25,000 in May 1959.

However, the threat of Communist power frightened Qassim.

In July, attention was centered on Kirkuk, where an ICP-led demonstration degenerated into a massacre of Turkmens, who were prominent in the city’s commercial elite. Qassim used the Kirkuk events as a pretext to repress the ICP. He ordered the CP-led militia, the Popular Resistance Force, disbanded, arrested hundreds of Communist supporters and sealed the offices of the General Federation of Trade Unions (which had been taken over by the ICP).

A plenum of the ICP Central Committee responded with an obsequious self-criticism declaring that its demand for participation in the government had been “a mistake” because it “led to the impairment of the party’s relations with the national government”—in other words, it displeased Qassim. The plenum declared a “freeze” on Communist work in the army, and informed the ranks that it was carrying out an “orderly retreat.” The Russians supported and demanded this. They sent to Baghdad, George Tallu, a member of the Iraqi Politburo, who had been undergoing medical treatment in Moscow, with an urgent request to the Iraqi party to avoid provoking Qassim, and to withdraw its bid to participate in the government.

In February 1963, the Ba’ath Party was able to broker a military coup that brought down Qassim and unleashed the counterrevolutionary furies. Using lists of Communists supplied by the CIA, the Ba’ath Party militia, the National Guard, launched a house-to-house search, rounding up and shooting suspected communists. An estimated 5,000 were killed and thousands more jailed, many of them hideously tortured by Saddam Hussein and others.

The CIA’s role in the 1963 Ba’ath coup has been widely documented. King Hussein of Jordan told the Egyptian daily Al-Ahram shortly after the coup that he knew “for a certainty” that U.S. intelligence services provided names and addresses of Communists to be killed. The State Department has confirmed that Saddam Hussein and other Ba’athists had made contact with the American authorities in the late 1950s and early 1960s. At this stage, the Ba’ath were thought to be the ‘political force of the future,’ and deserving of American support against ‘Qassim and the Communists’.”

Meanwhile, the ICP’s record of betrayal was not forgotten. When Kurds rebelled against the Qassim regime in 1961, the ICP denounced their revolt as “serving imperialist designs.” In 1972, when Saddam Hussein allied for a while with the Soviet Union, two ICP leaders who had not had their eyes gouged out in his prisons joined his government. The Kurds maintained their strong base in the Iraqi labour movement and were especially strong in the Kurdish oil industry.

In 1975, the left factions of the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP) seceded and formed their own party, the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (‘PUK’) under Jalal Talabani. Some of the differences between the KDP and the PUK are ideological, but there are strong inter-tribal distinctions between them as the PUK members tend to be urban, employed and members of the labour movement.

In 1980, KDP leader Massoud Barzani was able to raise a force of around 5,000 men in Northern Iraq which he used to assist Iran in its war against Iraq. The PUK, however, had relatively good relations with the Ba’ath in Iraq, but when the Iran-Iraq War dragged on the PUK and the KDP managed to come together in a common purpose to conduct the Kurdish rebellion of 1983.

The PUK and KDP Kurdish militias of northern Iraq would rebel against Saddam Hussein in an attempt to form their own autonomous country. With the Iraqi occupation of the Iranian front, Kurdish Peshmerga (their military force), combining the forces of both the KDP and PUK, succeeded in retaining control of some enclaves with Iranian logistics and sometimes military support. The initial rebellion resulted in stalemate by 1985.

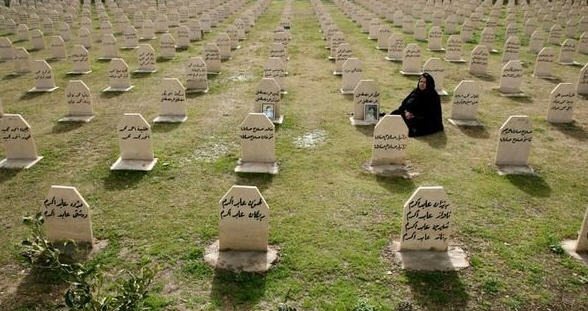

The Kurdish rebellion, largely a guerrilla war on the part of the Kurds, was met with the full armed hostility of the Iraqi state. Saddam Hussein expanded his oppression of Iraqi Shia, Kurds, Marsh Arabs and the minorities. In particular, the Ba’athists turned again against the Kurds during the Al-Anfal campaign of 1987–88. Saddam Hussein began an onslaught against the Kurdish people that eventually killed tens of thousands of Kurds and displaced at least one million of the Kurdish population to Iran and Turkey.

Ba’athist President Saddam Hussein had already shown a long history of a desire to suppress the Kurds with his attack on Halabja in March 1988. Halabja had fallen to Iranian and Kurdish forces which fought together against the Iraqis. The Iraqi counterattack was brutal and used chemical weapons on a wide scale, killing between 4,000 and 5,000 people and injuring 7,000 to 10,000 more, mostly civilians. Thousands more died of complications, diseases, and birth defects in the years after the chemical attack.

What became known as the Massacre at Halabja was part of the larger Ba’athist campaign against the Kurds and other minorities which they called the Al-Anfal campaign (also known as the ‘Kurdish Genocide’). Led by Hussein and headed by Ali Hassan al-Majid (‘Chemical Ali’), the campaign was a series of systematic attacks against the Kurdish population of northern Iraq, conducted between 1986 and 1989. The campaign also targeted other minority communities in Iraq including Assyrians, Shabaks, Iraqi Turkmen, Yazidis, Jews, Mandeans and others.

Unfortunately for the Kurds they were not a united people, deeply divided between the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (‘PUK’) and the Kurdistan Democratic Party (‘KDP’); the Talabani vs. the Barzani Kurds. Although autonomy in Iraqi Kurdistan had been created in 1970 (as the Kurdish Autonomous Region), the two Kurdish opponents could not agree on a common policy or leadership. There were Kurdish factions in the governorates of Erbil, Dahuk and As-Suleymaniyah which supported the Iraqi government, and others who supported a separate autonomous Kurdish state.

By the 1992 Kurdish election to the Legislative Assembly, power was shared almost equally between the Barzanis and the Talabani. That was unwelcome to both sides and tensions grew.

The Iraqi Kurdish Civil War began in May 1994 when fighting broke out between the two factions. The clashes left around 300 people dead. Over the next year, around 2,000 people were killed on both sides. Members of the Iranian Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps provided limited support to the KDP and allowed the KDP to launch attacks from Iranian territory. This fighting among the Kurds and the involvement of the Iranians in supporting the civil war was upsetting to the U.S. as it was then planning on how to confront the challenges Saddam Hussein was creating for Western interests in Iraq.

The CIA and Robert Baer

In January 1995, CIA case officer Robert Baer went to northern Iraq with a five-man team to set up a CIA station. The station in Erbil is still in operation. He made contact with the Kurdish leadership and was able to negotiate a truce between the Barzani and Talabani. Together they began to assist those who were planning to remove Saddam Hussein.

Baer and his team agreed to support an Iraqi general who was planning an assassination of Saddam Hussein. The assassination attempt was set to occur in Tikrit during a surprise attack on the Iraqi Army by the joint Kurdish forces in support of some rebel Iraqi troops. Saddam Hussein was warned about this by his Jihaz Al-Mukhabarat Al-Amma (intelligence service). Once Mukhabarat became aware of the plot it was leaked to the Turkish Milli Istihbarat Teskilati MIT (the Turkish intelligence service), which passed it on immediately to the US National Security Advisor, Tony Lake. Lake cabled Baer that the cover was blown, and the station in Erbil notified the Barzani who pulled back from the plan.

Somehow the Talabani were not informed. The PUK carried out the attack on its own. They managed to destroy three divisions and took around 5,000 prisoners before they were forced to withdraw. Baer cabled Washington on four occasions requesting US military assistance for the PUK, but no help arrived. He was later charged with planning the assassination of Saddam Hussein, but was cleared.

There was still no agreement between the two Kurdish factions. The Barzani KDP gradually took over the control of Kurdistan by allowing the Iraqi Government to establish a smuggling route through Kurdistan for its sanctioned petroleum exports through the Kabur River Valley, to the Turkish port of Ceyhan. The Barzanis allowed and protected this smuggling, imposing a heavy tax on the smuggled oil. This would earn the KDP over three and a half million dollars a week from the Iraqis.

Eventually they would agree to share some of this money with the PUK, but the KDP remained in control. This was not acceptable to the Talabani who then built an alliance with Iran and linked the PUK with the Pasdaran (Iranian’s Revolutionary Guard). In early 1996, they launched a joint attack on the KDP to get a bigger share of the revenues. Massoud Barzani would call upon Saddam Hussein to protect him from the PUK.

On August 31, 1996, 30,000 Iraqi troops, spearheaded by an armoured division of the Republican Guard and the KDP, attacked the PUK headquarters in Erbil which was defended by 3,000 PUK Peshmerga led by Korsat Rasul Ali. Erbil was captured, and Iraqi troops executed 700 PUK soldiers in a field outside Erbil while the KDP watched. The loss of Erbil was a blow to the U.S. and the use of Iraqi troops by Saddam Hussein in Kurdistan violated UN Security Council Resolution 688. In response, the Clinton administration began Operation Desert Strike when American ships and B-52 bombers launched 27 cruise missiles at Iraqi air defence sites in southern Iraq.

The next day, 17 more cruise missiles were launched from American ships against Iraqi air defence sites. The United States also deployed strike aircraft and an aircraft carrier to the Persian Gulf, and the extent of the southern no-fly zone was moved northwards to the 33rd parallel.

In September 1988, the U.S. was able to compel the Kurdish factions to stop their strife and sign the Washington Agreement establishing a formal peace treaty between them. They agreed to keep the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) out of Kurdistan to satisfy the Turks and to share the revenues equally between them.

As the UN’s Oil-for-Food Program had begun, the Kurds had a lot more revenue to spend from Iraqi oil exports. Most importantly, the U.S. guaranteed the security of Kurdistan. The Kurds assisted the U.S. in the 2003 war with Iraq and took prominent roles in the aftermath. Massoud Barzani became President of Iraqi Kurdistan and Jalal Talabani became President of Iraq. This guaranteed the continued access of the U.S. to Iraqi oil. That continued access was important because there was a new problem in the region which threatened U.S. and Western interests.

KRG Oil

The U.S. had observed the rise of Islamic fundamentalism, which was expanding in the region, after the Yemen Hotel Bombings in 1990. A new group had formed under the leadership of Osama Bin Laden, called al-Qaeda, whose influence was spreading throughout the Middle East, Afghanistan and Pakistan.

In August 1998, al-Qaeda carried out the bombings of the U.S. embassies in Nairobi, Kenya, and Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, killing more than 200 people and injuring more than 5,000 others. In October 2000, al-Qaeda succeeded further in attacking U.S. interests with the bombing of the USS Cole.

On September 9, 2001, al-Qaeda assassinated Ahmed Shah Massoud, the leader of the U.S. – supported Northern Alliance in Afghanistan which led to the takeover of the country by the Taliban. The most momentous act was the destruction of the World Trade Center in New York on September 11, 2001 with almost 3,000 people killed. It was clear that some major response from the U.S. was required.

The Second Gulf War removed Saddam Hussein and the Ba’athists. The Kurdish Peshmerga troops would aid in his downfall. Both Barzani and Talabani took positions of great power in the new Iraq and Saddam’s generals and security men moved to Syria, where they were welcomed by their fellow Ba’athists in the Syrian government. They went on to establish al-Qaeda and later Daesh in Syria.

The Kurdistan Autonomous Regional Government was formed again and KDP leader Massoud Barzani became President of the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG). That gave the Kurds a great deal of control over the oil industry and cemented a strong relationship with Turkey, which handled the delivery of Iraqi Kurdish oil at a very hefty premium via Ceyhan. The Turkish ties with the Kurds have been through their relationship with the Barzanis. The Talabani were effectively cut out of the financial windfall, as Barzani maneuvered to keep the ‘Kurdish’ oil for the KRG in the sustained conflict with Iraq’s new Shia leaders.

The rise of the predominantly Shia Maliki Government in Iraq and the concomitant empowerment of the Shia in the running of Iraq was very deleterious to restoring harmony in the country. This was especially true in the question of Iraqi oil, much of which was in the KRG. Big multinational petroleum giants took over the nation’s oil fields. Between 2009 and 2010, the Maliki government granted contracts for developing existing fields and exploring new ones to 18 companies, including ExxonMobil, Royal Dutch Shell, the Italian Eni, Russia’s Gazprom and Lukoil, Malaysia’s Petronas and a partnership between BP and the Chinese National Petroleum Corporation. When they started, the U.S. military provided the initial security umbrella protecting all their field operations.

The oil companies did not want to deal with Iraqi unionists in the oil industry. It was the oil companies who pressed the Ministry of Oil to enforce Saddam’s 1987 labour law which the government resurrected in 2003. As the Oil Ministry spokesman, Assam Jihad, told the Iraq Oil Report in 2010, “Unionists instigate the public against the plans of the oil ministry to develop [Iraq’s] oil riches using foreign development.”

The Iraqi government had to suppress dissent. This has been a recurrent theme in Iraq’s oil industry. Oil companies receive oil concessions, a low rate of compensation for land use, a subsidised price for oil to compensate for the cost of drilling, and social legislation which prevents dissent from spreading. Until recently, U.S military and U.S. Department of Defense contracted private armies have stood behind the oil majors in suppressing this dissent.

This dissent grew even worse when the Islamic State began a lightning assault on Iraq from its Syrian headquarters. The Maliki government had consistently refused to pay workers what they were owed and had been conscripting and press-ganging workers into Shia militias to fight the Daesh occupiers. The legitimate unions also feared Daesh, which seemed to see any autonomous organisation by workers as a threat.

The Iraqi government has for years refused to give up Saddam Hussein’s anti-trade union legislation, and several Iraqi political parties have tried to infiltrate unions or destabilise them for party political interests. Just days before Daesh entered Mosul in Northern Iraq, the Iraqi union leader in Mosul, Hussein Darwish, was assassinated on his way to work. Family members of the previous ITU President, Ahmed Jassam Salih, were also assassinated.

The only safe place for unionists in Iraq was in the resurgent Kurdistan and the KRG. There the Barzani-Talabani political accommodation has always included a role for the Kurdish workers and their organisations.

The Kurds took over direct control of the vast oilfields of Mosul and Kirkuk. Kurdistan became the last hideout of Iraqi labour. The Al-Abadi election has reduced tensions, but little progress has been made.

![Image PKK founder Abdullah Ocalan was sentenced to death by a Turkish court in 1999 [EPA]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/Kurdistan-Workers-Party-PKK.jpg)

When Abdullah Öcalan was captured and jailed in 1999, the PKK began a period of negotiation in search of a truce with Turkey; a process which resulted, in 2013, with a ceasefire with Turkey. This lasted until June 2015 when Turkey unilaterally broke the truce and attacked PKK bases in Iraq with continuous bombing raids. Turkey continues to engage in punitive bombings and terror inside the Kurdish areas of Turkey.

The Kurdish struggle has grown in intensity inside Turkey. This struggle is central to the regional strife which is now confronting Syria by Turkey’s reaction to the growing strength of the Kurds inside Turkey and in the Rojava in Syria.

TO BE CONTINUED in PART 2: The Kurds in Turkey and Syria

Dr. Gary K. Busch, for Lima Charlie News

Dr. Busch has had a varied career-as an international trades unionist, an academic, a businessman and a political intelligence consultant. He was a professor and Head of Department at the University of Hawaii and has been a visiting professor at several universities. He was the head of research in international affairs for a major U.S. trade union and Assistant General Secretary of an international union federation. His articles have appeared in the Economist Intelligence Unit, Wall Street Journal, WPROST, Pravda and several other news journals. He is the editor and publisher of the web-based news journal of international relations www.ocnus.net.

Lima Charlie provides global news, insight & analysis by military veterans and service members Worldwide.

For up-to-date news, please follow us on twitter at @LimaCharlieNews

Sources

[i] Ward, R.S. Immortal: A Military History of Iran and its Armed Forces. 2009. pp.231–233.

![STRATEGIC OPTION | Syrian Endgame - The Hard Truth [Lima Charlie News][Photo: Bulent Kilic]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/STRATEGIC-OPTION-Syrian-Endgame-e1558501175322-480x384.png)

![Image The Alevis Dilemma [Lima Charlie News]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/Alevis-Erdogan-480x384.png)

![Africa’s Elections | In Malawi, food, land, corruption dominate [Lima Charlie News]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/Malawi-election-Food-land-corruption-480x384.jpg)

![Image The Rwandan Jewel - Peacekeepers, Conflict Minerals and Lots of Foreign Aid [Lima Charlie World]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/Rwanda-Jewel-480x384.jpg)

![Image [Women's Day Warriors - Africa's queens, rebels and freedom fighters][Lima Charlie News]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/Womens-Day-Warriors-Lima-Charlie-News-480x384.jpg)

![Image Zimbabwe’s Election - Is there a path ahead? [Lima Charlie News]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/Zimbabwe’s-Election-Is-there-a-path-ahead-Lima-Charlie-News-480x384.png)

![[Silver lining for China in Zimbabwe’s violent elections][Lima Charlie News]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/Screen-Shot-2018-08-02-at-12.51.35-PM-480x384.png)

![STRATEGIC OPTION | Syrian Endgame - The Hard Truth [Lima Charlie News][Photo: Bulent Kilic]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/STRATEGIC-OPTION-Syrian-Endgame-e1558501175322-150x100.png)