The U.S. Senate has just passed a bill expanding the sanctions against Russia imposed earlier in response to Russian aggression in Ukraine and its seizure of Crimea. In addition, Russian threats against Baltic nations and Western interests in its military campaign to preserve the Assad regime in Syria have added to the desire for increased international sanctions. Coupled with this, is a strong reaction to the realisation that Russia attempted to interfere in the recent U.S. election.

The major impact of these proposed sanctions is on Russia’s gas and oil industries – the lifeblood of the Russian economy where Western nations and companies are prohibited from engaging with Russian oil and gas producers and prohibited from passing on technology to Russian firms. This interdiction will be a dramatic inhibitor of Russian advances in Arctic offshore, deep water, and shale projects, and the planned second Nord Stream pipeline.

This type of restriction on the transfer of technology to Russia is not new. Russia not only needs cash, investments and an unhindered access to world markets, it desperately needs technology, especially in the oil and gas sectors, as well as for its aging military industries.

During the Cold War the West established the CoCOM (Coordinating Committee for Multilateral Export Controls). It made the transfer of technology to the Soviet Union subject to a license and a strict control of the efforts by the Soviets to get Western technology. This was changed in 1964 to the Wassenaar Arrangement. It placed heavy penalties on violators of this technology ban but also banned any contract between the violating company and the U.S. Government. The program was regulated in the Arms Export Control Act and the International Traffic in Arms Regulation. Current economic sanctions against Russia are derivatives of this policy, administered by the Treasury.

The Senate bill expands U.S. restrictions in two important ways. First, it brings projects in which Russian companies are involved—regardless of where they are located—under the purview of sanctions. That means Russian companies will be denied the opportunity to amass expertise in advanced drilling techniques by participation with Western partners or by hiring the Western firms as consultants. Secondly, the bill requires the executive branch to impose sanctions on foreign firms that make significant investments in next-generation Russian oil projects. The strongest sanctions in the bill, similar to the CoCom controls, prohibit transactions with Russia’s intelligence and defence sectors.

Another important aspect of the bill is the sanctions on investment in the construction of Russian energy export pipelines. If the Treasury Department invokes this provision, it will threaten sanctions against any company that makes a significant investment in Russian-European pipelines, like the Nord Stream 2; the proposed gas pipeline that would connect Russia to Germany by way of the Baltic Sea. Under current sanctions, U.S. financial institutions cannot provide credit to the six largest Russian banks with maturity of thirty days or more. The bill tightens the debt maturity threshold to fourteen days

Most importantly, the Senate bill locks in existing U.S. sanctions against Russia into law (as opposed to Executive Order) and gives Congress a check on the president’s ability to lift sanctions. The announcement of the passage of the Senate version of this bill has produced a howl of outrage from Germany, the main architect of the project.

However, eight Eastern European states have denounced the EU bureaucracy led by Germany for approving the Nord Stream 2 project, and Poland has begun a series of legal moves to block it. Ambrose Evans-Pritchard notes:

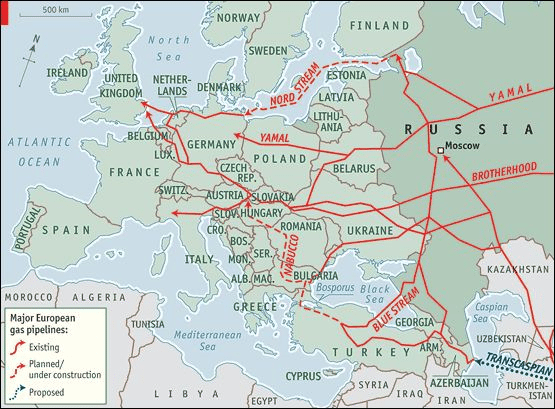

“There is one basic point to remember about the Nord Stream 2 pipeline from Russia to Germany: it does not add any extra natural gas supply to the European market for the foreseeable future. This Molotov-Ribbentrop 2 pipeline – as the furious Poles call it – diverts the same Siberian gas from existing pipelines on land: the Yamal link through Belarus and Poland; and the ill-named Brotherhood link through Ukraine to South-East Europe. These pipelines are both in working order and running well below full capacity. They need updating but are essentially sunk costs, and require no ecological upheaval. The Nord Stream 2 venture creates a sweetheart arrangement with Germany while undermining the security and economic interests of Eastern and Central Europe, and leaves Ukraine at the mercy of Kremlin blackmail.” [i]

The pipeline, itself, is inherently vulnerable to attack. This second set of Nord Stream pipeline tubes will be located between fifteen and twenty metres of water under the Baltics, easily accessible to a terrorist with a canoe or a rowboat, leaving 75 per cent of the EU’s gas imports (excluding Norway) vulnerable to terrorist attacks. The pipelines run through two munition dumps in the Baltic. Only half of the 85,000 Baltic mines laid in two world wars have ever been recovered. Nord Stream 1 had to be closed in 2015 when the Swedish navy discovered an underwater drone rigged with explosives nearby.[ii]

There are several big companies which have signed up to the €9.5bn costs of Nord Stream 2; Germany’s BASF, EON, Uniper and Wintershall, Austria’s OMV, Engle in France, and Shell. All have operations in Russia, or have pipeline contracts with the Russian gas giant, Gazprom. Gazprom will shoulder 50% of the cost of the 55 billion cubic metre pipelines, which is due to start operating in 2019. Gazprom has already received more than €1 billion from its partners for Nord Stream 2 financing.

A joint statement was issued by the Germans and the Austrians the day after the Senate vote. Exclamation points were included:

- “We can not, however, accept the threat of non-international extraterritorial sanctions against European companies, which are involved in the expansion of the European energy supply!”

- “Europe’s energy supply is a matter for Europe, not the United States of America!”

- “Foreign policy interests must in no way be linked to economic interests! There is still enough time, and opportunity, to prevent this!”

These are clearly not comments that could be open to misinterpretation, and have triggered a new diplomatic spat. Germany and Austria said the potential U.S. sanctions had brought a “new and very negative” quality to US-Europe relations and there has even been talk already in Berlin of reciprocal sanctions against the U.S.

The main moving party is Germany whose business community has been adamantly against sanctions of any kind against Russia. German business associations and foreign policy experts are urging Merkel that the policy of sanctions be ended. They argue that sanctions practically have become ineffective, since Russia’s economy has withstood these trade restrictions and is now even recovering. Moreover, Russian orders, that German businesses had once expected, were increasingly going to competitors, for example in China – and are ultimately lost. However, German economists still see Russia as a lucrative market.

Germany’s exports to Russia had declined by almost 50 percent – from 38 billion euros in 2012 to 21.5 billion in 2016. This trend seems to have reversed. In the first two months of 2017, German exports to Russia grew by 38 percent in comparison to the same period a year ago, reaching four billion euros. German direct investments in Russia have also increased and could reach 2.5 billion euros in 2017 – from a volume of 1.95 billion in 2016, according to the DIHK. However, due to the substitution of imports in the last three years, the shares of German enterprises in Russia’s agricultural sector have been lost.

German mechanical engineering may have permanently lost its top position in Russia. Last year, German exports of machines and installations to Russia, totalling 4.4 billion euros, fell behind Chinese exports worth 4.9 billion. Moscow has even begun the strategically significant oil drilling in Russia’s Arctic, on its own.

The battle is more than just German economic ambition. The control by Gazprom over the gas supply of Western Europe has already led to shutdowns of Ukrainian pipelines. On 1 January 2006, when Russia cut off all gas supplies passing through Ukrainian territory, supplies through Ukraine to Western Europe were cut off. There were similar incidents in 2008 and 2009 when Gazprom cut or reduced gas volumes through Ukraine. Gazprom is still very much bound up in the European Commission antitrust case against it, accused of abuse of its dominant position in gas markets in central and eastern Europe. The shutdowns prompted a revision of the policy of energy dependence on Russian exports, with an effort to obtain alternate sources to reduce the dependence.

This was a short-lived ambition in Germany which relies on pipelines from Russia. Russian state-backed Gazprom, Europe’s largest supplier of gas, was responsible for arranging supply. Nord Stream 2 would increase Russia’s share of the German gas market to over 50 percent, from 43 percent of its imports in 2015. Poland already receives more than two-thirds of its natural gas supply from Gazprom. Nord Stream 2 backers also note that European domestic gas supply is set to decline by 50 percent over the next 20 years, and the fear is that the pipeline would mop up a significant amount of this developing import gap, deepening European reliance by discouraging imports from elsewhere. As first suggested in 2015 there is a virtual EU Energy Union designed to maximise efficiency and security of supply in the EU but there is little unity or uniformity in its progress.

This dependence of Europe on Russian imports has two major aspects. The first is that this dependence on Russian supplies has, until recently, been largely dependent on the reliability of pipeline supply through Ukraine. After Russia’s aggression on Ukraine the two have not been able to agree on price and availability of gas supply through the pipelines which transfer Russian gas to Western Europe. The North Stream pipeline, the existing and the planned, is a Russian scheme to bypass Ukraine gas storage and transmission pipelines and move the supply out of the reach of Ukraine. The Russian problem with Ukraine is a political and military problem, not an economic problem. It will not be resolved by gas supply lines alone.

Germany’s willingness to abandon Ukraine by dealing directly with the Russians in diverting the gas supply lines is not a solely economic choice. It is a political statement of the primacy of Germany’s Russian relations over the oft-stated EU support for Ukraine in its resistance to Russian domination. This has caused a great deal of friction within the EU and its Energy Union, especially among the states on Russia’s western borders and the Baltics. The EU has an ongoing antitrust case against Russia which Germany is ignoring. Kiev would, of course, be the main loser once Nord Stream 2 is built. It stands to lose its $2 billion/year in transit revenues if gas is diverted away from the Ukrainian route. It also stops Ukraine transporting gas to Slovakia and then buying it back at EU prices to escape punitive tariffs. It enables Russia to play a divide-and-rule game that splits the EU, and that sweetens Germany with preferential pricing.

This was not the first time that German gas policy impacted Ukraine. When the Russians turned off the gas tap through Ukraine in January 2009 these threats to the EU were made real when the Russians reduced exports of gas to Europe by 60%. The Europeans pressed for some sort of a compromise. The dispute was framed as a commercial dispute over prices and payments but there were far more strategic concerns involved – the Black Sea Fleet. While the U.S. supported the Ukrainians in their defiance of the Russian threats, the Europeans pressed for some sort of a compromise which would let the gas flow to their countries.

The Ukrainians were caught in the middle. Europeans were desperate for the Ukrainians to do whatever it took to assuage the Russian gas threat while the U.S. and its NATO allies pressed the Ukrainians to follow through on ending Russian leases which allowed them a presence in the Black Sea. Despite the arguments brought forth in favour of each of these policies, a realistic assessment of the situation was made that there was no substitute at that time for Russian gas so a compromise would have to be reached with the Russians.

After much discussion, a compromise was reached and the Ukrainian and Russian parliaments, on 27 April 2010, ratified a deal to extend the lease on the Russian naval bases in Ukraine for 25 years after the then current lease expired in 2017. In return, Ukraine received a 30% discount on Russian natural gas. The Europeans got their gas restored. The Europeans then began an accelerated process to bring the government of Ukraine under its wing which could prevent further confrontations on the transport of gas.

Although Ukraine was not very interested at that time in joining NATO, it was interested in establishing a relationship within the aegis of the European Union. However, on the 25th of February 2010, the EU’s Ukrainian partners, Yuschenko and Timoshenko, lost control of Ukraine in the national election of a new President, Victor Yanukovych. That meant that the ratification of the treaty extending Russian occupation of the naval bases was being considered by the Rada (Parliament) under a political majority controlled by Victor Yanukovych and his Party of the Regions. The ratification process of the treaty in the Rada took place amid violent protests by the opposition, which called the deal an “act of treason”. Despite the protests, the Rada ratified the treaty on 27th of April 2010.

The European Union continued to encourage Ukraine to move closer to accession. However, the first thing Europeans wanted was to control Ukrainian energy policy so that they could protect the European-wide price of gas. In December 2009, the EU Energy Community Ministerial Council decided on the accession of Moldova and Ukraine to the EU.

On December 15, 2010, Ukraine ratified the Energy Community Treaty and became a full Contracting Party of the Energy Community with a legal commitment to adopt EU energy, competition and environmental Directives.

Obligations of Ukraine as a party to EC included:

- To implement certain provisions of European legislation acquis communautaire on issues related to electricity, gas and environment according to the specified schedule

- To follow the rules for competition and state assistance, envisaged by the Agreement on foundation of European Community

- To approve the plans of development and implementation, stipulating energy infrastructure and policy in the field of RES, which have to comply with accepted EU standards.

In May 2010, President Yanukovych promised to adopt the legislation necessary for creating a free trade zone between Ukraine and the European Union. Further discussions in the next year led to proposals for even closer bonds between the EU and Ukraine. However, Yanukovych refused to sign the agreement with the EU because his supporters, primarily in his Eastern heartland, were bitterly opposed to the terms of the accession to the EU. They had come with a long list of economic austerity programs which were an integral part of the agreement. There was a great deal of upset within Ukraine at the refusal of the government to sign the agreement and there was a repeat of the occupation by protestors of the Maidan Square (now called the Euro-Maidan).

The betrayal of Ukraine by the EU was a direct result of the EU’s demand for unfettered access to Russian gas, especially Germany, and the unreasonable demands for Ukraine to swallow the bitter pill of German austerity for any assistance.

A wave of demonstrations and civil unrest began on the night of 21 November 2013 with public protests in Independence Square in Kiev, demanding closer European integration. These protests expanded and became a movement for the resignation of Yanukovych and his government.

By 25 January 2014, the protests had been fuelled by the perception of “widespread government corruption”, “abuse of power”, and “violation of human rights in Ukraine”. Violence intensified and there were shootings and beatings on all sides. There were about 80 dead and 600 wounded in clashes at the square.

The economic situation was dire. Ukraine was running out of money. It turned first to its erstwhile partners in the EU. The Prime Minister asked for 20 billion Euros (US$27 billion) in loans and aid. The EU was only willing to offer 610 million euros (US$ 838 million) in loans with harsh conditions on the Ukrainian economy which would have required heavy austerity and changes to the law. On the other hand, Russia offered US$ 15 billion in loans and cheaper gas prices without the onerous demands for an austerity program.

Later that day, the 21st of February 2014, the President felt that his time was up and that civil war was looming. He fled to Kharkiv and later to Russia, abandoning his post. The Rada met the next day to impeach Yanukovych for being unable to perform his duties. The stealth invasion of the East by Russia began a few weeks later.

This betrayal of Ukraine by the EU was a direct result of the EU’s demand for unfettered access to Russian gas, especially Germany, and the unreasonable demands for Ukraine to swallow the bitter pill of German austerity for any assistance. Ukraine, and most of the EU members from Eastern Europe and the Baltics see the new Nord Stream 2 project as an extension of this policy direction.

The second aspect of the resistance to the Nord Stream 2 project is that it is out of date and locking Europe into a system with great inefficiencies and inflexibility. The use of pipelines to carry gas is important internally to distribute gas but very inefficient in importing gas. The object of gas supply is to obtain maximum flexibility in supply and achieving the lowest cost for its acquisition. The technology of gas transmission has changed with the spread of new gas suppliers from all over the world and the rise of the U.S. shale gas industry.

Many Europeans would like the flexibility provided by a free and transparent [natural gas] market but the Germans dominate the EU and its rules are changed and suspended to satisfy German requirements.

The Supply of Liquified Natural Gas (LNG)

Traditional transportation of natural gas has been done through a web of pipelines which criss-cross North America as well as through a smaller concentration of pipelines in Europe, Asia and the Middle East. Natural gas is pumped through these pipelines and delivered to distribution points which take the gas received and delivers it to customers. Nothing is done to the gas but pressuring and blowing it through the pipeline. The nature of the gas remains unchanged. This is a sufficient system to transfer and deliver gas on land as the pipeline carries the gas from point to point using valves and blowers. However, pipeline transport is very inefficient in the moving of gas between non-adjacent and distant countries as the volume of the gas is better and more flexibly managed by specialised marine vessels.

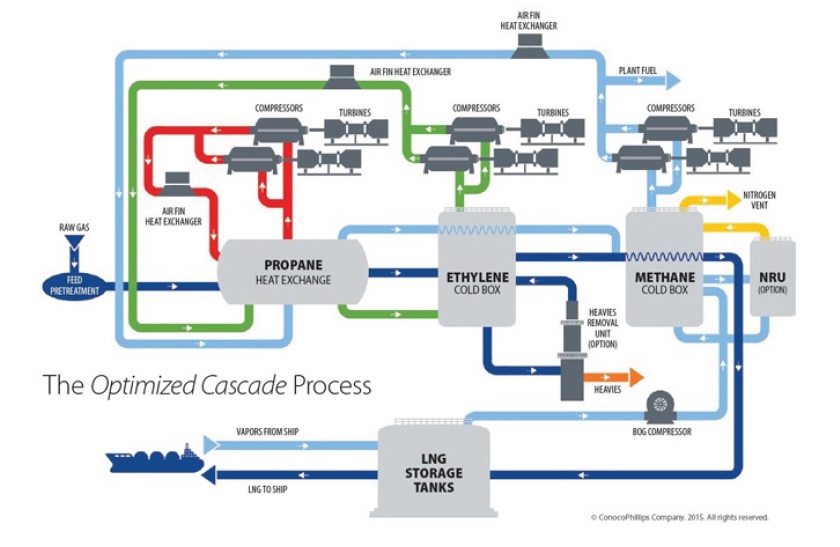

The response to this challenge of storing and shipping natural gas was to use cryogenic procedures to liquefy the natural gas through refrigeration to less than -161° Centigrade (the boiling point of methane at atmospheric pressure). By liquefying the gas, the volume of the gas is reduced 600 times, making it easier to store and to ship. The freezing of the natural gas is done in a specialised unit called a “train”. It includes a process of purification of the gas before it is frozen so the Liquefied Natural Gas is free of impurities.

Each LNG plant consists of one or more trains to compress natural gas into the liquefied natural gas. A typical train consists of a compression area, propane condenser area, methane, and ethane areas. They are very expensive to build and operate. These trains are fed by pipelines from the land which pass the liquefied gas into specialised marine vessels docked at the train. These vessels are loaded alongside the train and sail to a receiving train at the import end. The process is reversed on delivery in a receiving, regasification, train.

Marine Vessels For the Transport of LNG

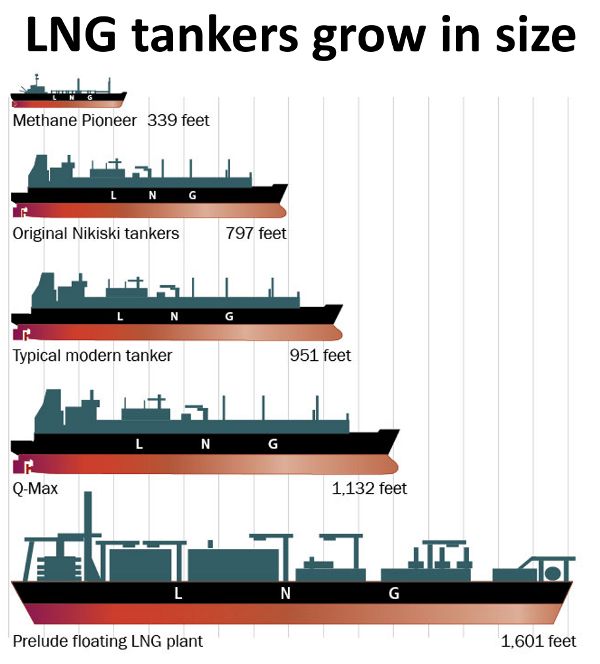

Liquefied gas cannot be loaded into normal bulk carriers or tankers. The vessels used to carry LNG are like giant Thermos bottles. They are built like conventional tankers but include a variant of one of two systems. LNG carriers have grown in number as the trade in LNG has increased.

Most LNG vessels are around 950 feet, with about 10.2 metres draught and carry between 125,000 to 175,000 cubic metres of gas. In 2013 these LNG vessels carried about 11.5 trillion cubic feet of LNG.

Most LNG vessels are around 950 feet, with about 10.2 metres draught and carry between 125,000 to 175,000 cubic metres of gas. In 2013 these LNG vessels carried about 11.5 trillion cubic feet of LNG.

The Lithuanian Floating Storage and Regasification Unit

By far the most innovative change in LNG shipping is the world’s first liquefied natural gas (LNG) floating storage regasification unit (FSRU). It is a vessel which sits in the port, receives LNG cargos from vessels alongside and regasifies the LNG on board without the need for an expensive regasification train on the quay. The FSRU, built at an estimated cost of $330million, is now a major entry point for LNG into Lithuania and its neighbours. It was ordered in June 2011 and the first steel was cut in September 2012. It was christened Independence in a naming ceremony held at Ulsan in February 2014. The ship arrived in Klaipeda Port to start operations during December 2014.

The Independence’s storage capacity is significant – at 6 million cubic feet or 170,000 cubic metres – it can handle almost 140 billion cubic feet a year of natural gas. This means the FSRU has the capacity to supply 100% of Lithuania’s current demand of natural gas, allowing them to forgo reliance on pipelines and unpredictable Russian supplies. Until recently Lithuania – like many of its neighbours – had relied almost exclusively on Gazprom to fulfill domestic consumption demands.

More Baltic nations are now following Lithuania’s lead, turning seaward for energy supplies rather than to the traditional overland gas pipelines. Poland has prepared an LNG import terminal of its own at Świnoujście. The Baltic states are quite well-connected with pipelines and have decent infrastructure connecting all three countries with pipelines. This has been the case for over the last 10 years, but had never been used for trading because each had their own suppliers and no trade was arranged with others, despite the significant differences in price. Now, Lithuania traders are currently supplying around 20% of Estonia’s natural gas supplies and look to supply more to the Baltics as well as to the larger Polish market.

In addition to vessels like the Independence which can create an almost instant LNG import facility in the port, Shell has pioneered the use of a floating vessel to liquefy natural gas at sea. After years of discussion and investments, the first Floating LNG project, Shell’s Prelude, was announced in 2011. Today there are over twenty other FLNG projects and its business is sized to exceed 60 Billion USD for the next decade.

While liquefaction is traditionally performed onshore, Floating LNG literally displaces the entire process to the top of a vessel, located nearby a sub adjacent offshore gas field. Thanks to this shift, the need for an extensive pipeline structure to shore as well as a production platform is eliminated, thereby potentially reducing the cost of taking the gas to the market. Moving the liquefaction offshore also facilitates the permitting process, reduces the risks for neighbouring communities as well as the impact on the environment. Additionally, there is a possibility to relocate the vessel at the end of its project life to a different offshore point.

By far the most rapid rate of growth of supply of natural gas into the international market is the U.S. as a result of the exploitation of shale gas. With the rapid increase in domestic natural gas production, the U.S. is becoming a net exporter of natural gas. The Department of Energy has now authorized a total of 21 billion cubic feet of gas per day (Bcf/d) of natural gas exports to non-free trade agreement (non-FTA) countries from planned facilities in Texas, Louisiana, Florida, Georgia, Maryland, and now, with Delfin, from the Gulf of Mexico. In addition to the numerous gas export trains in the U.S. the U.S. Department of Energy has approved the nation’s first long-term application to export gas from a floating LNG terminal. Delfin LNG will be able to export 1.8 Bcf/d from its proposed Louisiana floating offshore LNG terminal in the Gulf of Mexico. The facility, jointly owned by the India and Singapore-based Fairwood Group and the U.S.-based Peninsula group, is expected to be operational in 2020.

It is clear that U.S. exporters can supply most of Europe’s gas needs efficiently, cheaply, and without the political baggage of a Russian pipeline. The Senate bill brings that point home sharply and the Germans seem to prefer the Russians as partners. Many Europeans would like the flexibility provided by a free and transparent market but the Germans dominate the EU and its rules are changed and suspended to satisfy German requirements.

German and French military corporations continue to supply the Russians with military equipment in violation of the existing sanctions agreement.

The Military Gulf in Atlantic Relations

The questions arising from the Nord Stream 2 project are indicative of the German and French positions on supervising the operations of the existing sanctions policy against Russia. They exist in theory but are studiously avoided in practice. The recent NATO meetings brought many of these concerns to the fore.

In 1949, it made some sense to create an alliance to preserve the unity of the wartime alliance in the face of the perceived Communist threat in Soviet-occupied areas of Eastern Europe and the outbreak of the Korean War. The unequal relationship between U.S. military might and economic muscle and the pitiful remnants of the Western European armies and a “degraded” European infrastructure was tolerated by U.S. planners because they knew that if a vacuum was left there were candidates ready to fill it. The goal, according to Lord Ismay, the first NATO Secretary General was “to keep the Russians out, the Americans in, and the Germans down”. The Americans obliged by creating NATO as a common defence organisation and used the Marshall Plan to restore Europe’s economy.

NATO solved the problem of commitment by instituting a culture of planning. With a clearly understood mission, NATO planners (composed of representatives from all the constituent nations except France from 1968 to 1995) analysed every possible contingency. For every contingency, they generated a plan. For every plan, they allocated forces. For every force, NATO devised endless training exercises designed to make execution as automatic as possible. This was NATO’s main achievement; it created a system of automated, conditioned responses that were to be executed so rapidly that participants did not have the time or opportunity to pause, reflect and potentially renege.

The planning and exercise process, quite apart from being necessary for military preparedness, was also an instrument that psychologically and operationally locked in the actors. Under such circumstances, given the doctrine and the plan that applied, units in Fort Bragg, North Carolina, the Netherlands, and Sicily all went into motion. In operational terms, the goal was to make the commitment of forces as thought-free as possible. Even complex war fighting doctrines like Air-Land Battle, which foresaw a fluid and unpredictable battlefield, still contained highly routinized, automated procedures for the initiation of and response to conflict. NATO’s internal battles were referred to countless planning cells that packaged a basic strategic challenge into an array of automated responses.

In many respects, scenario construction, contingency planning, war gaming, and repetitive exercises was the only thing holding NATO together, staving off the fear of a last-minute double-cross. However, by 1992, the rock on which the church rested, the Soviet threat had largely disappeared or, like the smile on the Cheshire Cat, appeared only when required. Without that threat, contingency planning collapsed. Financial contributions to the NATO budget, while never adequate, declined as the Europeans sought to reap the windfalls of peace.

Europe, despite its elaborate plans and rhetoric about a European Defence Force, has refused or been unable to pay for the maintenance of their national militaries. Defence spending has dropped from an already low level by around 15% in the last ten years. This general statement masks the fact that the biggest cuts have been in the adequate provision of transport aircraft. Most of the transport of military personnel in NATO has had to be done by the U.S. Left on their own the Europeans would have to walk, paddle or catch cabs to the frontline.

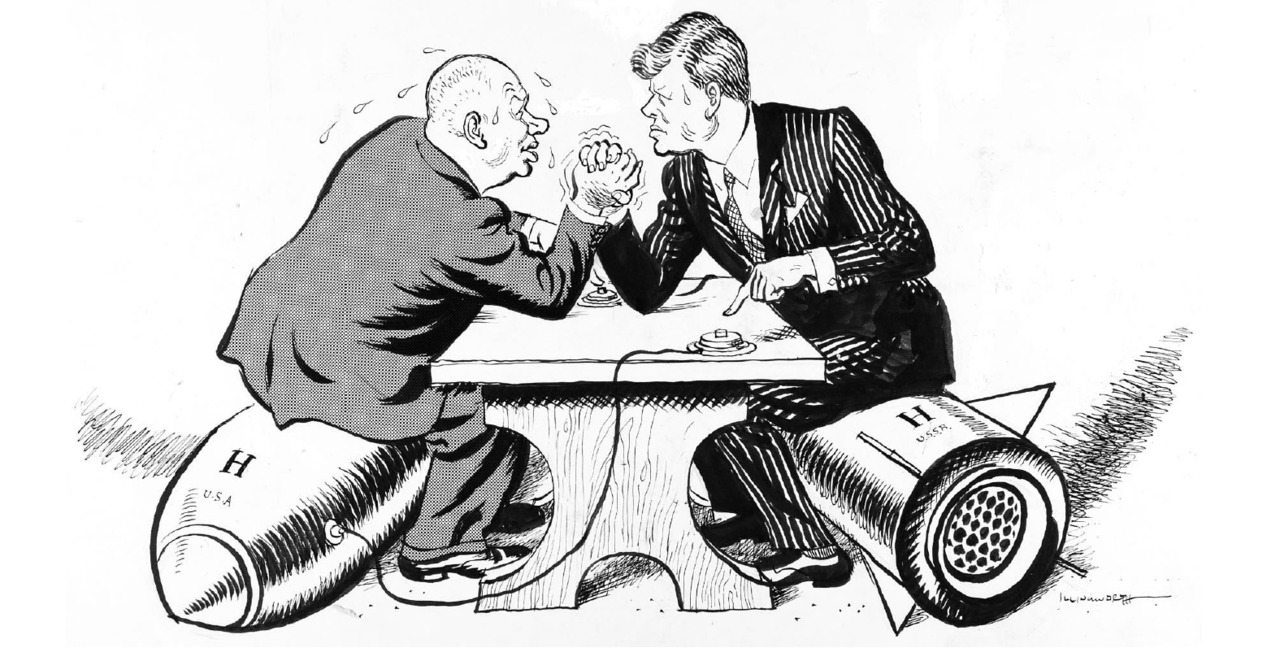

There is a recurring myth that somehow European unity has maintained the peace on the continent since the end of the Second World War. This is a preposterous self-delusion. Europe’s peace was maintained because half of Europe was occupied by the U.S. and the other half by the USSR until 1990. The U.S. and the USSR had the good sense to keep their European allies in check because of the danger of Mutual Assured Destruction which would result from the two major nuclear powers moving beyond a cold to a hot war. It had very little to do with Europeans.

The decline in military strength, in addition to shortfalls in NATO budgets, has been most manifest in Germany and France. Until very recently, there has been only a decline in European self-defence capabilities. In a recent study (February 2016) “Alliance at Risk Strengthening European Defence in an Age of Turbulence and Competition” the European failings and shortfalls were highlighted. Europe’s leading armed forces are so hollowed out they are incapable of conducting major rapid-response operations.

The U.S. spends 3.6 per cent of its economic output on defence. Germany spends a pitiful 1.2 per cent; and what little Germany does have tends not to work. When Angela Merkel made the grand gesture of sending weapons to Kurdish rebels fighting ISIL, her cargo planes couldn’t get off the ground. At the time, the German military confessed that just half of its Transall transport aircraft were fit to fly. Of its 190 helicopters, just 41 were ready to be deployed. Of its 406 Marder tanks, 280 were out of use. Last year it emerged that fewer than half of Germany’s 66 Tornado aircraft were airworthy.

Not only is the budget below German’s security needs, it is being spent primarily on personnel, not equipment or repairs. This has resulted in an army that can only fight for 41 hours a week and not on the weekend. German soldiers taking part in a four-week NATO exercise in Norway earlier this year had to leave after just twelve days because they had gone over their overtime limits. However, the troops are comfortable. The German Defence Minister, Ursula von der Leyen, has used the military budget to introduce creches for children on the bases, along with flat-screen TVs. Postings are limited to match school term dates.

The French military has overrun its military budget on numerous occasions, although it has many troops stationed in Africa maintaining African despots in power. Its budget too is well below the NATO limit of 2%. Even when it does make its investments in equipment the process has, at times, been an elaborate charade. The best example, perhaps, is the pride of the French Navy, the nuclear aircraft carrier Charles De Gaulle. During its construction, the ship ran into huge cost overruns. Work on it was stopped four times. By the time it was completed the rules for radiation shielding had changed and it had to be refitted with radiation shielding to protect the crew. Moreover, the ship’s flight deck had to be extended by about fourteen feet to accommodate the Hawkeye as the type of plane the carrier would support had changed over the long time of construction.

The propulsion system was even worse. When it went to sea it vibrated so heavily that the propellers snapped. When they went to repair it, they found that the blueprints for the propellers had been lost in a fire, which meant the ship had to be refitted with hand-me down screws from Foch and Clemenceau. That cut her speed down from twenty-seven knots to about twenty-four knots—which was unfortunate since she is already considerably slower than her predecessors which steamed at thirty-two knots. She went for a refit in 2007. In 2010 when she set out for the Mediterranean it took only one day out of port for there to be an electrical fault and tugboats had to put her in position. She is now mainly functional.

And yet, despite this inadequacy, German and French military corporations continue to supply the Russians with military equipment in violation of the existing sanctions agreement.

Although Germany and France do not supply the Russian government directly, they deal with small intermediary companies in Russia which have sprung up to make the deals. A good example is the Limited Liability Company “Industriya-Service” which has been successful in securing multi-million tenders for supplying equipment to Russia’s defence industry for many consecutive years. Despite having a share capital of fifty roubles, Industria Service deals with the biggest suppliers. The first was YXLON International (PHILIPS Industrial X-Ray GmbH). Other customers include Daimler AG, BMW, VW, EADS, Honsel, Superior, Alcoa, Thyssen Krupp, Goodyear and Bridgestone.

In a recent article in 2012, the director of “Industriya-Service” mentioned other German partners, too, such as KOWOTEST, JUTEC and Schwarze-

German firms sold equipment to the Gas Turbine Engineering Research and Production Centre “Salut” which produces engines for the Su-27SM, Su-33, and Su-34 in 2015, and to the Central Research and Development Institute of Chemistry and Mechanics in May 2015. The latter is “the leading organization in the country in the field of scientific and technological breakthrough solutions for advanced weaponry”. German companies sold their solutions to the Academician Pilyugin Scientific and Production Centre of Automatics and Instrument-Making which develops missile technology in June 2015.

Germany has continued to supply the Russian defence industry in 2016. The Science and Technology Centre “Atlas” acquires German products. The centre operates “in the field of information security for the benefit of federal agencies of the governmental authorities of the Russian Federation, law enforcement agencies as well as other customers”. German goods are also procured by the “Raduga” State Engineering Design Bureau, a global leader in the field of high-precision missiles. From a single deal involving German solutions, the defence conglomerate the “Technodinamika” Group is set to make 159 million roubles (approximately 2.5 million euros).

Germany also sells its goods to Russia’s FSB. For example, it sells products to the 43753 military unit which used to be part of the eighth main KGB administration of the USSR. It is now in control of the means of cryptographic protection of information as well as the 34435 military unit – The Institute of Criminology of the 11th Centre of the FSB of the Russian Federation – which “reconstructs the psychological profile of a suspect based on their handwriting, identifies their appearance, and partial biography from their voice, and can carry out identification based on a speck of dandruff”.

The “Geophysics” Central Design Bureau which is part of the Corporation “Strategic Control Points” announced the purchase of tools by the German company PFERD on July 5, 2016. The “Luch” Research and Development Institute-Scientific and Production Facility which “has been involved in development and supply of fuel elements to the nuclear and defence industry” purchased German “Spectromat” equipment worth 38 million roubles. The Vavilov State Optical Institute – the leading research and development establishment in optics in the field of industrial and defence-industrial sectors – purchased technology made by Trioptics GmbH in July. The Russian Nationwide Research and Development Institute of Aircraft Materials which develops materials and technologies for combat aircraft buys tooling made by Walter.

The Ulyanovsk Mechanical Plant – the main producer of air defence systems – which manufactures “Buks”, “Tunguskas”, “Shukla’s” and “Pantsuits” – purchases measuring equipment made by Rohde and Schwartz. The “Stresa” Scientific and Production Facility which produces military radars buys German machines made by Optimum.[iv]. The Iskander missiles which were recently moved with some fanfare to Kaliningrad are made with German tooling, German lubricants and German components.

Germany is not the only country which supports the Russian military.

France supplies materials to “Aviakompozit” which produces nose cowlings for military aircraft. Italy sells goods to the “Iskar” defence plant as well as the “Salut” enterprise. The latter is part of the “Tactical Missiles” corporation. The Netherlands also supplies goods to “Tactical Missiles”.

Perhaps the most interesting supply of military goods to Russia was by Rheinmetall Group which built an important Russian army training centre (RATC) in Mulino, 350 km (217 mi.) east of Moscow. The project began in June 2011 and delivered in 2014. Many of the “little green men” are graduates of the program at Mulino. Rheinmetall developed and supplied the live combat-simulation system and oversaw technical implementation of the project, including commissioning and quality assurance. It delivered the training management and information system, laser engagement systems for 1,000 players—both vehicles and soldiers—the exercise control centre, Tetra data communication system, instrumentation for three military operations in urban terrain (MOUT) facilities, and the warehouse and fitting facility. Mulino is capable of training 30,000 troops a year. This base at Mulino was the first of two bases to be constructed by Rheinmetall, but the second was interrupted by the Russian seizure of Crimea. The Germans are waiting for sanctions to end to build the next training base.[v]

According to the Congressional Research Service, Rheinmetall’s partner in the deal was the Russian state-owned Oboronservis (“Defence Service”) firm. U.S. officials believe that some of the German training over the last few years was given to the GRU Spetsnaz, the special operations forces that moved unmarked into Crimea and who can now be found stirring up trouble in eastern Ukraine.[vi]

It is not only the Germans who have been playing fast and loose with the foundation stone of the EU arms transfer control system, the legally binding EU Common Position 2008/944/CFSP. In 2011 France agreed on a contract to supply Russia with two Mistral-class amphibious assault ships – the first major arms sale to Russia by a NATO state. Even the EU arms embargo on Russia, introduced on 31 July 2014, failed to prevent the sale, exempting as it does pre-existing deals. Russia provided €893 million (US $978 million) in advance payment for the two Mistral helicopter carriers. Under extreme international pressure the French didn’t deliver the Mistrals to Russia; it sold them to Egypt and repaid the Russians some of the money it has delivered. The knowledge of how to build such ships was passed on to Russians during the years of construction and the Egyptians seem willing to allow the Russians to jointly use the vessels for common projects.

With all the questions about Nord Stream 2 pipelines, gas supply and aid and trade with the Russian military it is difficult to see the advantages of working closely with and supporting either the German or French military. They seem less than fully committed to the aims and aspirations of the Atlantic Alliance and NATO. The tragedy is that this is all developing from the policy vacuum of both the Obama and Trump presidencies. Perhaps, one day, the U.S. electorate will elect a government that can join-up the several strands of foreign policy commitments and develop a coherent strategy instead of short-term fixes.

Dr. Gary K. Busch, for Lima Charlie News

[Edited by Anthony A. LoPresti]

Dr. Busch has had a varied career-as an international trades unionist, an academic, a businessman and a political intelligence consultant. He was a professor and Head of Department at the University of Hawaii and has been a visiting professor at several universities. He was the head of research in international affairs for a major U.S. trade union and Assistant General Secretary of an international union federation. His articles have appeared in the Economist Intelligence Unit, Wall Street Journal, WPROST, Pravda and several other news journals. He is the editor and publisher of the web-based news journal of international relations www.ocnus.net.

Lima Charlie provides global news, insight & analysis by military veterans and service members Worldwide.

For up-to-date news, please follow us on twitter at @LimaCharlieNews

Sources

[i] Ambrose Evans-Pritchard, “Germany’s gas pact with Putin’s Russia endangers Atlantic alliance”, Telegraph June 21, 2017

[ii] ibid

[iii] Yuri Lobunov, “Germany, a partner of the Russian military?”, Intersections 29/12/16

[iv] ibid

[v] Nicholas Fiorenza, “Rheinmetall Works on Combat Training Center In Russia”, Aviation Week & Space Technology, Sep 3, 2012

[vi] Josh Rogin, “Germany Helps Prep Russia for War”, Daily Beast April 22, 2014

In case you missed it:

![Blossoming Russo-Turkish alliance leaves U.S., NATO behind [Lima Charlie News]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/Russia-Turkey-alliance-leaves-U.S.-NATO-behind-480x384.png)

![Image Russia and China’s 'hybrid warfare' - Does the West even care? [Lima Charlie News]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/Russia-China-Hybrid-Warfare-02-480x384.png)

![image NATO’s value can’t be measured in nickels and dimes [Lima Charlie News]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/NATO-Trump-0005-480x384.png)

![Image Murder, genocide, politics and the almost surrender of Radovan Karadžić [Lima Charlie News][Lima Charlie World]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/Radovan-Karadzic-001-480x384.png)

![Image The Alevis Dilemma [Lima Charlie News]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/Alevis-Erdogan-480x384.png)

![Blossoming Russo-Turkish alliance leaves U.S., NATO behind [Lima Charlie News]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/Russia-Turkey-alliance-leaves-U.S.-NATO-behind-150x100.png)

![Image Russia and China’s 'hybrid warfare' - Does the West even care? [Lima Charlie News]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/Russia-China-Hybrid-Warfare-02-150x100.png)