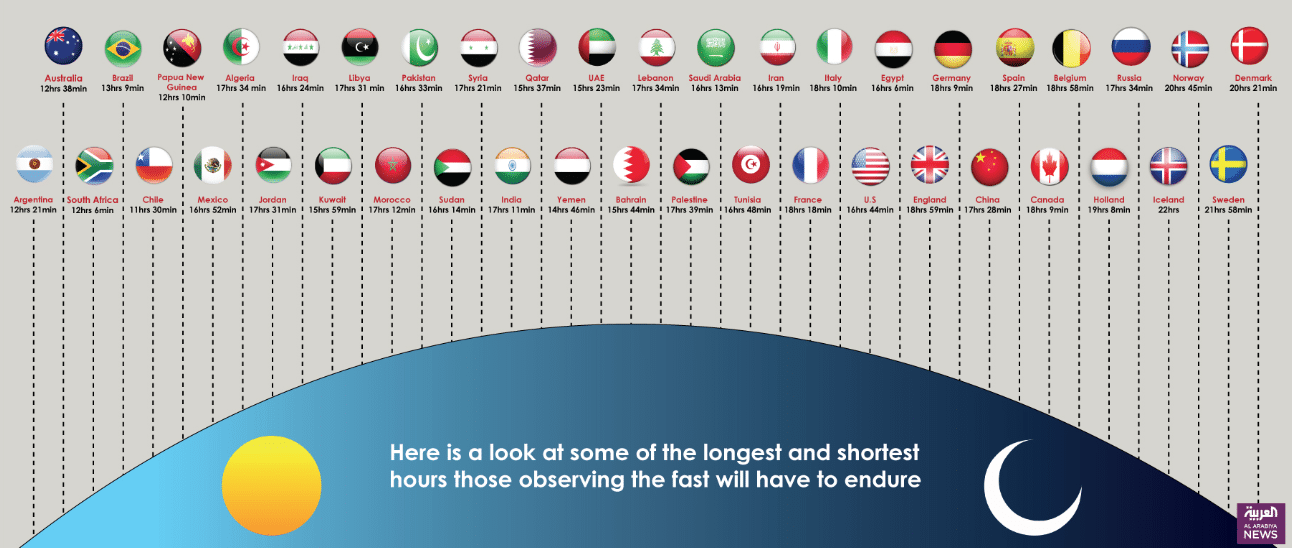

Islam-related commerce is on a sharp rise throughout the world, at a growth rate twice that of the baseline global economy. Does observing the holiest month of Islam, Ramadan, a sacred duty that any true believer must adhere to, adversely impact the productivity of the region?

The holiest month of Islam, Ramadan, is in full swing. With it comes the obligation or fard, of fasting for religious reasons during the daylight hours. It is a sacred duty that any true believer must adhere to. Subject to a few exceptions, fasting includes abstention from food and drink, as well as smoking and sexual activities.

Ramadan also means that many shops and restaurants that operate in the predominantly Muslim region of the Middle East will see increases in sales, as people break their fast with a celebratory feast, called an iftar at sundown or by giving gifts to their loved ones.

Yet, statistics show that the month of Ramadan can also lead to reduced GDP growth in Muslim countries, despite a regional GDP that is on a sharp rise.

On assignment for Lima Charlie News, I visited Riyadh, the capital of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia before the beginning of Ramadan to examine geostrategic developments in the region. I arrived during the Hilal, the day after the astronomical new moon, marking the beginning of the holy month. It was unavoidable that the upcoming Ramadan celebration would soon be a topic of discussion.

While shopping for dates, an export product that the Kingdom is particularly known for, along with oil and carpets, I wandered into a fruit market alongside Prince Abdullah bin Abdul Aziz Street, in Al-Rahmaniyah. I was accompanied during this excursion by “Salam,” a long-standing acquaintance and member of the Kingdom’s security services.

Salam and I discussed price awareness before and after the beginning of Ramadan. Items that are traditionally consumed or purchased for celebrations include dates, perfumes, Qur’ans, and miswaak – a kind of twig from the Salvadore Persica tree that is used to brush one’s teeth. Miswaak belongs to the traditional Islamic hygienic jurisprudence that is part of the salat, the prayer routine. All of these products, along with traditional headwear, rise in price before Ramadan, only to drop back below their original price during Ramadan.

“Sales might increase during Ramadan,” Salam said, “but those shopkeepers of the faith won’t really make much more money. Ramadan is ostensibly about being seen as helping people, so they often raise their prices before Ramadan to make up for being able to symbolically lower the price during the celebration.”

Salam added, “Those shopkeepers that are really smart about it can even be seen as giving something away for free during Ramadan. That keeps everyone fairly happy.” Salam’s viewpoint is one often expressed by the more cynical minded, with the words changing, but the sentiment remaining.

Indeed, British brands such as The Body Shop, Godiva and MAC Cosmetics have all developed particular products for the feast. These include halal lipstick and chocolate truffles to make the end of Ramadan, the celebration of Eid al-Fitr (June 15th this year), as fanciful as possible.

Islam-related commerce is on a sharp rise throughout the world. It sees a growth rate twice that of the baseline global economy, this according to a report by the Reuters affiliated State of the Global Islamic Economy study group. In fact, if the trend continues at its present velocity, the projected global market size in such sectors as halal food, travel, fashion, media, recreation, pharmaceuticals and cosmetics will reach over 3 trillion USD by 2021.

![Image [Graphic courtesy of Thompson Reuters State of the Global Islamic Economy 2017-2017]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/Thompson-Reuters-State-of-the-Global-Islamic-Economy-2017-2017.jpg)

Lebanese Economics Minister, Raed Khoury, encouraged shopkeepers in the days leading up to Ramadan to keep the price gouging under control this year. “Think of your fellow man,” the minister was quoted saying in the Lebanese press.

The price gouging before Ramadan is, however, mostly a short-term consumer level problem. The real question is how it might affect the regional economy at large. Any change on such a strategic level could have far-reaching consequences that outlive the Ramadan celebrations all the way until the end of the year.

Two researchers at the Harvard Kennedy School, Filipe R. Campante and David Yanagizawa-Drott, released a study back in December 2013, addressing that issue. Titled “Does Religion Affect Economic Growth and Happiness? Evidence from Ramadan,” the study concluded that Ramadan has a direct adverse effect on the productivity of Muslim society.

The study examined data from six decades and found that the GDP growth of Muslim countries drops significantly during Ramadan. Longer days, combined with working on an empty stomach, often found workers having a difficult time focusing on the job.

According to the study, research found “significant prevalence of individuals reporting tiredness and unwillingness to work, as well as reduced levels of activity and concentration ability, during the month of Ramadan,” especially when under conditions of heat and humidity. Apparently, this leads to a general “slowdown” in work and productivity. The study cites to “robust evidence” of a causal effect of longer Ramadan fasting on economic growth, with an overall detectable 0.7 percentage drop in efficiency per additional hour of fasting. Evidence also suggested that Ramadan has a negative impact on labor demand, “with a decrease in labor supply, or possibly both.”

The study also found “direct suggestive evidence that Ramadan fasting affects work-related individual beliefs and values. Specifically, Ramadan leads Muslim men to report that they care relatively more about religion and less about work and material rewards.” It concluded that, “religious practices can affect labor supply choices in ways that have negative implications for economic performance, but that nevertheless increase subjective well-being among followers.”

The study is clear, however, that despite a negative impact on the economy, there is an increase in levels of self-reported happiness and life satisfaction among Muslims. This aspect was mirrored in an earlier study, and an article titled “The Ramadan Debate: Spirituality vs Productivity,” by an organization called ProductiveMuslim Ltd., that posited:

“A productive Ramadan is about asking oneself the critical question: How can I be the best version of myself — spiritually, physically, and socially during this blessed month? If enough Muslims ask themselves this question and follow through with practical implementation of the latest productivity science that helps them be productive, healthy and balanced human beings, then perhaps in a few years we might get a different result from the Harvard Kennedy School of Government research, one that will say Ramadan not only improves subjective wellbeing among followers, but also improves economic performance and productivity.”

To underscore his point, Salam brought me to a quaint restaurant and asked how Ramadan would impact business this year.

Specialising in traditional Arab cuisine – lots of chicken and lamb – the restaurant had plastic tables and plastic chairs both inside and out on the sidewalk. Inside, a ceiling fan pushed around cool air from an air conditioner living a hard life, rarely being set above meat locker temperatures. The grey-haired owner detached himself from the outdoor open grill to answer Salam’s question. His name is Salaf, and he is originally from Iraq.

“Wait,” he said, as he walked back into the restaurant, to reemerge a minute later holding a big cash box. On the top of the box was an opening to put coins and bills into. “Those that can afford to, donate money to feed the poor, especially during Ramadan,” he said. “It is ironic,” said Salaf, “that it is during Lent they can give to the poor the most.”

Salaf rejected Salam’s opinion that Ramadan has turned into a cynical and commercial spectacle. “No, it is now that the poor can eat like a King, either for free or at least at a reduced price.”

With a satisfied smile he continued, “During Ramadan, we (the shopkeepers) hurt, but the more we give, the more we make during the rest of the year.”

No doubt the shopkeeper’s viewpoint, one often uttered, is ultimately self-serving. But for the starving and impoverished – what difference does that make? Indeed, during Ramadan they can eat well.

John Sjoholm, Lima Charlie News

John Sjoholm is Lima Charlie’s Middle East Bureau Chief, Managing Editor, and founder of the consulting firm Erudite Group. A seasoned expert on Middle East and North Africa matters, he has a background in security contracting and has served as a geopolitical advisor to regional leaders. He was educated in religion and languages in Sana’a, Yemen, and Cairo, Egypt, and has lived in the region since 2005, contributing to numerous Western-supported stabilisation projects. He currently resides in Jordan. Follow John on Twitter @JohnSjoholmLC

Lima Charlie provides global news, insight & analysis by military veterans and service members Worldwide.

For up-to-date news, please follow us on twitter at @LimaCharlieNews

In case you missed it:

![Image Marketing to Islam - Does the holy month of Ramadan affect economic growth? [Lima Charlie News][Photo: Anniesa collection]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/Marketing-to-Islam-Does-the-holy-month-of-Ramadan-affect-economic-growth.png)

![Africa’s Elections | In Malawi, food, land, corruption dominate [Lima Charlie News]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/Malawi-election-Food-land-corruption-480x384.jpg)

![Syria’s oil, gas and water - the Immiscible Solution to the War in Syria [Lima Charlie News][Photo: ANDREE KAISER / MCT]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/Syria’s-oil-gas-and-water-480x384.png)

![Image The Rwandan Jewel - Peacekeepers, Conflict Minerals and Lots of Foreign Aid [Lima Charlie World]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/Rwanda-Jewel-480x384.jpg)

![Image Russia's energy divides Europe [Lima Charlie News]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/Russias-energy-divides-Europe-Lima-Charlie-News-480x384.png)