While the Trump Administration’s “America First” policy may be damaging to U.S. free trade worldwide, America’s inability to maintain deep water access at its seaports is a far more critical enemy than any new tariff or duty. Thanks to historic “America First” legislation, American seaports have failed to keep up.

The introduction of an “America First” policy on international trade by the Trump administration, especially the new tariffs on steel and aluminum, have posed a problem for American importers of these commodities. The retaliatory threats by China, NAFTA and the European Union of a trade war on hundreds of other commodities will sharpen the blow to U.S. exporters if the trade wars happen. Negotiations are taking place in an effort to avoid such a trade war, but some effects of this impediment to the free flow of goods among nations are bound to occur.

Yet, this notion of “America First” is not the most damaging aspect of U.S. trade policy. America’s inability to maintain deep water access at its ports – a policy which stops much of the modern commercial fleet from entering U.S. waters or loading or discharging to capacity in U.S. ports – is a far more critical enemy of U.S. free trade policy than any new tariff or duty.

![Image [The Port of Los Angeles, also called America's Port, is one of the US's largest seaports]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/Port-of-Los-Angeles.jpg)

America’s “America First” Past and the U.S. Shipping Industry

American seaports are too shallow to allow many of the modern ships used in international trade to reach its ports or pass through its sea channels. The primary reason for this inadequacy can be traced to two pieces of Congressional “America First” legislation.

The first law was passed on May 28, 1906. The Foreign Dredge Act stated that “A foreign-built dredge shall not, under penalty of forfeiture, engage in dredging in the United States unless documented as a vessel of the United States.” Originally enacted due to a controversy arising over the use of “foreign-built dredges” to repair damage done by a hurricane at Galveston, Texas, the law was passed to protect American shipbuilding against foreign competition. It was amended slightly in 1992 but it remains intact and operative.[i]

As a result of this protectionist law, U.S. ports could only be dredged by a vessel constructed by a U.S. manufacturer (or, as amended in 1992, on a vessel whose hull was built in the U.S.). There are very few dredgers which have been built in the U.S., especially the high-cost capital dredgers used around the world, so few are available for engagement.

A second piece of legislation has been almost as devastating to U.S. commerce as the Foreign Dredge Act. The Merchant Marine Act of 1920 (better known as the ‘Jones Act’), is “an act to provide for the promotion and maintenance of the American merchant marine, to repeal certain emergency legislation, and provide for the disposition, regulation, and use of property acquired thereunder, and for other purposes.” Passed by the 66th Congress on 5 June 1920, the Jones Act had the admirable purpose of promoting and protecting the American merchant marine.

Among other purposes, the Jones Act regulates maritime commerce in U.S. waters and between U.S. ports. Section 27 deals with cabotage (coastal trade), and requires that all goods transported by water between U.S. ports be carried on U.S. flag ships, constructed in the United States, owned by U.S. citizens, and crewed by U.S. citizens and U.S. permanent residents. [ii]

The Jones Act prevents foreign-flagged ships from carrying cargo between the US mainland and certain non-contiguous parts of the US, such as Puerto Rico, Hawaii, Guam and Alaska. U.S.-bound ships cannot stop at any of these four locations, offload goods, load mainland-bound goods, and continue to US mainland ports. Ships can, however, offload cargo and proceed to the US mainland without picking up any additional cargo intended for delivery to another US location. As a result, ships usually proceed directly to US mainland ports, where distributors then break bulk and send the goods to US destinations off the mainland by US-flagged ships. [iii]

Not only does the Jones Act require that all coastal trade be carried on U.S. vessels, it prohibits U.S. ship owners from buying foreign ships and then putting them on the U.S. register. It also states that any U.S. vessel that needs repair to its hull or superstructure can be repaired outside U.S. waters, but this is limited in that less than 10% of the steel for that repair can be derived from foreign steelmakers.

With this rock-solid protection, U.S. shipbuilders constructed vessels which were protected by the Jones Act, rather than competing directly with the major international shipbuilders of Japan, Korea, Malaysia and Singapore. They had a captive market and produced, at a very high cost, for that market.

As a result, less than 1% of international, non-military, shipping is built in the U.S. The U.S. lacks in technology, a skilled workforce, and a woeful lack of seamen to be an international transport force.

Just recently, American fishing company Fishermen’s Finest, headquartered in Washington state, commissioned the ship America’s Finest for $75 million from a shipyard in Washington. Under the Jones Act, however, America’s Finest is legally unable to fish in American waters and will not be hiring any American fishermen because the ship contains 7 percent steel that was cold-formed in the Netherlands, a process that the Coast Guard currently interprets as “fabrication.”

![Image [The Zhen Hua 20 in Brooklyn, New York, loaded with four container cranes from Shanghai, China to Elizabeth, New Jersey. Ships like this one can carry up to 6 fully tested container cranes and heavy components.]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/Zhen-Hua.jpg)

U.S. ports are inadequate

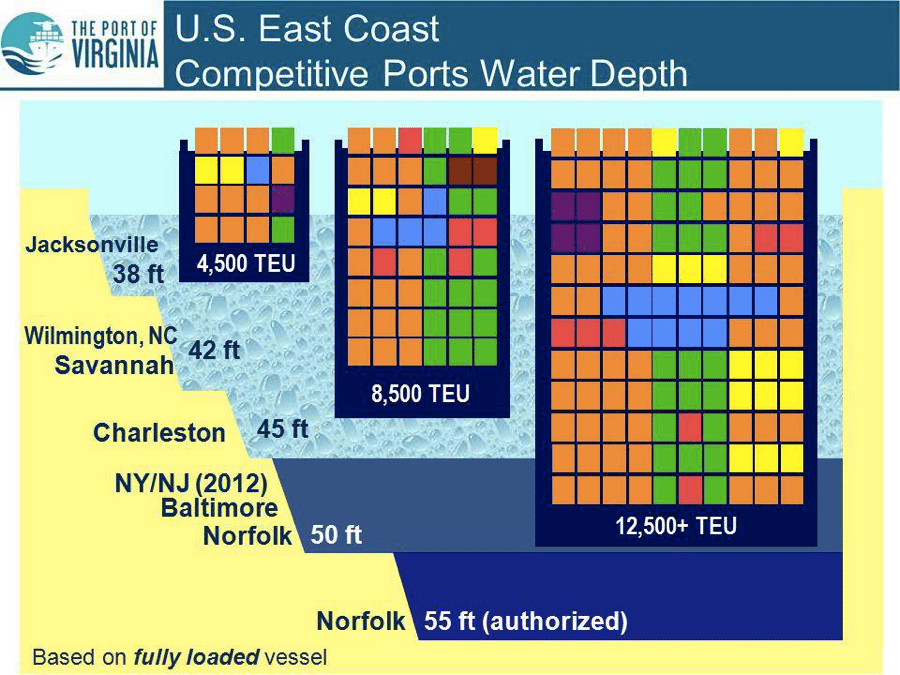

Today, only a handful of U.S. seaports can accommodate the most modern transport ships, which are 1½ times as large and can carry twice as much cargo as the typical vessel that makes port in America.

At least 10 of America’s busiest ports must expand to remain competitive with foreign ports. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers estimates this will take far more than a decade. [iv]

The basic problem is that the ports and their access from the sea are too shallow. They were never very deep at the best of times, but they require maintenance dredging to keep them clear and need to be deepened to allow large vessels to berth at the port and discharge and load their cargoes. There are insufficient U.S. built dredgers to perform the task, and those that exist are aged and decrepit. There has been, over the years, a woeful lack of dredging done in U.S. ports; the dredgers which did exist only worked less than half a year. They were never constructed to do the massive dredging tasks of the modern capital dredgers because there was insufficient work for them and they were too small or ill-equipped to handle major jobs.

![Image The Port of New York & New Jersey is the largest and busiest US east coast port and the nation’s third-largest [Image: Keith Schneider]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/New-York-NJ-Port-PA.jpg)

At this time I was sent to the U.S. as a consultant for Hochtief Dredgers from Germany. We had two large cutter suction dredgers just finishing off a dredge in the mouth of the Orinoco River in Venezuela.

I went to the Army Corps of Engineers and told them I could have two, world-class capital dredgers in New Orleans in less than three days. We reckoned we could cut a channel in the Mississippi in less than ten days. They were very excited. We met with several representatives from the ports and they were enthusiastic as well. The U.S. was losing hundreds of millions of dollars a day in the blockage.

They called a meeting along with Congress members from the area. I was then told that we couldn’t bring in our dredgers to open the river because they were foreign dredges, run by a foreign company. The Corps of Engineers and some Louisiana politicians said they would try to get an exemption based on a national emergency. Unfortunately, the politicians concluded that they couldn’t make an exception for something as sensitive as the Jones Act. They eventually found a company called Great Lakes Dredges that had a vessel with proper, foreign, equipment on it installed on a U.S. bottom. But it took months to clear the Mississippi. We could have done it for twenty percent of the price they paid, and in ten days.

This was a clear lesson about the high cost of U.S. protectionism. I had seen some of it before.

In another instance we were seeking to operate one of our floating cement silos in the port of Hampton Roads, Virginia. We had been in contact with several berths there. We agreed to use a Norfolk and Southern Railway berth which had handled Massey Coal exports. They had stopped coal exports because it was too expensive.

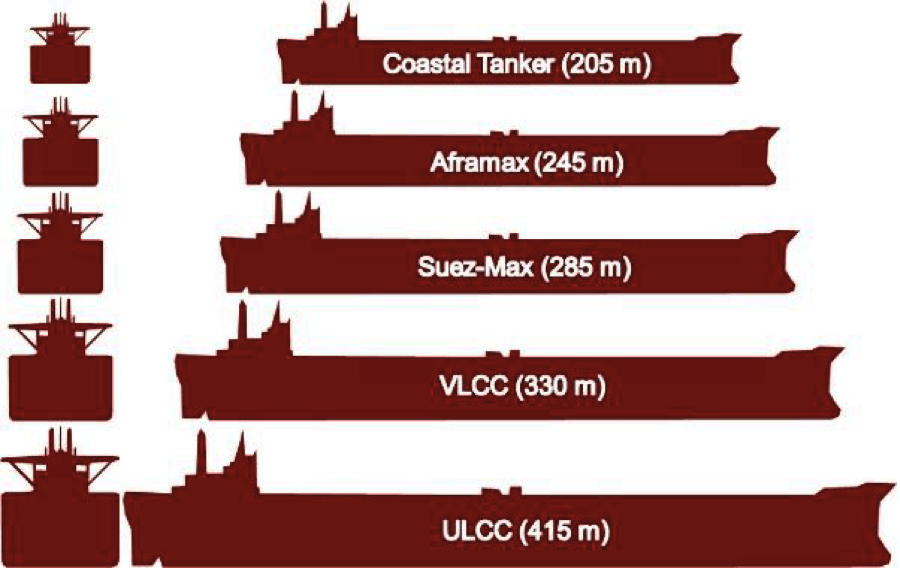

Most coal is shipped on giant Capesize vessels. These are very large and ultra large cargo vessels with a capacity of over 150,000 deadweight tons (DWT). They are categorised under VLCC, ULCC, VLOC and ULOC, and can be as large as 400,000 DWT or even more. They require around 18 meters draft (59 feet). That means to berth there must be 59 feet of water alongside the quay for the vessel to load.

Hampton Roads had a little over 12.5 meters draft, which meant that a vessel could not arrive at the berth and load a full cargo. It would arrive empty and could load slightly less than half its cargo capacity. It would then sail to South Africa where the missing cargo space was filled with South African coal. The cost of two load ports and delays made it too expensive to continue, so U.S. coal exports dropped dramatically. U.S. coal became uncompetitive because the ports could not handle the size of the vessels.

At Congressional hearings the question was asked, “How long does it take to get full approval for a dredging project?” The answer was astonishing. The lead time for originating a dredging project, and the day when dredging started was sixteen years.

In addition to planning and zoning applications, the acceptability of the equipment, and financial projections, there was the problem of what dredgers would do with the wastes and soil they removed. There are severe restrictions about dumping the spoils on shore and equally stringent rules about dumping them at sea. A waste schedule had to be prepared.

Included were the constraints on the “wetlands”. Did the project adversely affect the animals inhabiting the wetlands? Were there endangered species whose lives might be affected by the dredging? Were there red snails or crabs that were unique to the area being dredged? These and many questions had to be addressed. Public hearings had to be held and committees consulted. In many port areas this process extended over fifteen years.

A good example of this is the Port of Savannah, Georgia. In one example:

“After waiting more than 16 years for funding and approvals, work to deepen the Port of Savannah, Ga., began in September 2015. The project was expected to cost $700 million and be complete by 2020. Today, cost overruns surpass $270 million and the project is two years behind schedule.” [v]

The problem is that U.S. dredging companies simply aren’t capable of meeting demand. They do not have the proper equipment to perform these tasks in the way in which international dredging companies approach the problem. It takes specialised equipment and there has not been the demand on U.S. dredgers to modernise their equipment. They simply aren’t prepared.

The State of the Modern Dredging Industry

The four largest free-market dredging companies (a/k/a the Dutch dredging mafia) are based in Holland and Belgium. They have state of the art equipment. They could complete U.S. projects for less than half the project costs and in about a third of the time.

In the past decade, these companies have invested $15 billion in new dredgers, while the entire U.S. market invested only $1 billion. The European equipment is larger than any American company’s and handles more than 90% of the world’s open-bid dredging projects.[vi]

One of the largest and most modern dredging fleet is operated in China, where the offshore construction of floating island bases has engaged the Chinese Navy for a number of years. They built modern dredgers for this task. The top ten dredging companies of the world have very few U.S. members:

- Royal Boskalis Westminster

- CHEC (China Harbour Engineering Company)

- Van Oord

- DEME

- Jan de Nul

- Great Lakes Dredge and Dock

- Weeks Marine Inc

- Inai Kiara

- National Marine Dredging Company

- Hyundai Engineering and Construction

The size and capacity of modern dredgers, like the Chinese dredgers, dwarf U.S. dredging capacity and efficiency.

If there is one lesson to be learned it is that protectionism doesn’t work.

The Crisis in America’s Ports

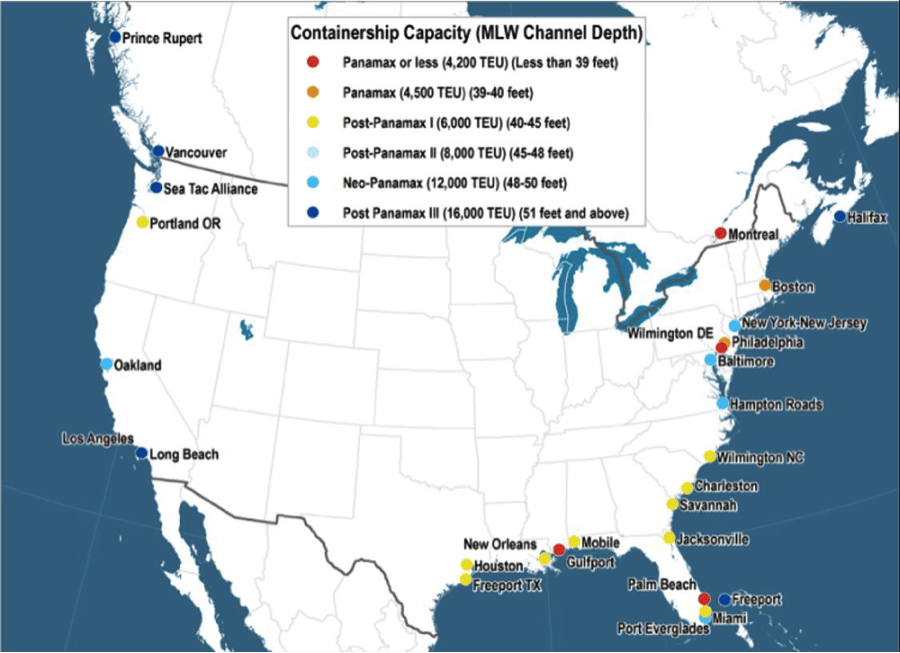

Because of the lack of dredging, American ports cannot handle the size of modern marine transport vessels, whether for dry cargo, oil and petroleum cargos, or for containers.

Dry cargo vessels, like the large Capesize vessels, are increasingly being used to haul grains, coal, ores and other bulk products. With a few exceptions most large Capesize vessels cannot access U.S. ports fully laden, nor can they fully load when alongside. This inhibition on size is magnified in the transport of oil and its derivatives.

Increasingly, oil is being transported on VLCC (very large crude carriers) or ULCC (ultra large crude carriers). The VLCC vessels are usually over 250,000 dead weight tonnage (DWT). These are used for the long-haul transport of crude oil. They usually draw more than 20 meters of draft (65 feet).

The ULCC vessels are the largest shipping vessels in the world with a size ranging between 320,000 to 500,000 DWT. They have a standard dimension of 415 meters length, 63 meters width and 35 meters draft (115 feet). A recently delivered vessel can carry 2 million barrels of oil. The economies of scale, however, diminish when the vessel cannot enter the port or find a suitable berth.

These petroleum and petroleum product carriers are usually defined by the passages they make; e.g. Suezmax is a vessel that traverses the Suez Canal or a Panamax through the Panama Canal. With the larger vessels, they stand off the berth and are loaded through a long catenary arm at mooring points near the berth, or by using smaller vessels to shuttle to the tanker to fill or empty it.

In April 2018, there was a noteworthy achievement when the LOOP (Louisiana Offshore Oil Port) was able to load a VLCC directly without having to use intermediary vessels. The LOOP is currently the only US Gulf Coast export facility that does not require Aframax or Suezmax vessels for reverse lightering onto a VLCC.

There is an even bigger problem with the staple of world trade shipping, the container ship. The large bulk of non-bulk shipping is carried in metal containers stacked in the holds and decks of a vessel. These, too, have grown in size and depth to match the volume of trade and to take advantage of the economies of scale which lower the unit cost of each container. Containers are measured in TEUs (the size of a twenty-foot standard container).

U.S. ports cannot handle the large new container ships currently in use.

Many of the container vessels in current use carry 10,000 to 11,000 TEUs and can berth at several East and West Coast ports. However, the trend is for the use of larger vessels which can’t enter the ports because of draft, and which require portal cranes to lift the containers on and off the vessels, which require cranes much taller than existing equipment.

The national picture isn’t much better.

There are an increasing number of Post Panamax vessels being delivered. Last year the East Coast was visited by the Chinese-owned COSCO Development, a vessel that carries over 13,000 TEUs. There are several larger containerships being delivered which seem likely to dominate the market for container shipping.

Protectionism Just Doesn’t Work

If there is one lesson to be learned it is that protectionism doesn’t work. It raises the costs for U.S. exports because they must be delivered on smaller vessels which are uneconomic compared to the vessels which are deployed by its competitors.

The Foreign Dredgers Act and the Jones Act perpetuate this lack of free competition in which all parties benefit. The legislative and executive branches of the U.S. government are derelict in providing the infrastructural funds to dredge and maintain American ports. This isn’t a party-political problem – all governments, Republican and Democrat, have failed in this endeavour. The U.S. has created its own monstrous non-tariff barrier to international commerce. What kind of a regulatory system requires sixteen years to process a single application?

One cannot just blame the American dredging companies for this situation. They are its prisoners as well. It was uneconomic to build and renew dredgers when one had no idea when the next project would begin. After sixteen years of negotiation and delay, the vessels they owned deteriorated. Many owned dredgers which could be used on a variety of dredging problems as the owners never knew which projects would be funded. It led them to manufacture “plain vanilla” dredges and the building of highly specialised cutter-suction dredges represented an investment whose returns were very uncertain.

This is a problem which must be addressed with some urgency. Forget steel, aluminium and similar quotas. The return on these tariff ploys are marginal at best and negative as a rule. Putting money into modernising U.S. ports is a better way to spend infrastructural funds and will yield a much higher and long-term return on the investment.

If one wants to “Put America First” one should surely unshackle the chains which bind its growth.

Dr. Gary K. Busch, for Lima Charlie News

[Edited by Anthony A. LoPresti]

Dr. Busch has had a varied career-as an international trades unionist, an academic, a businessman and a political intelligence consultant. He was a professor and Head of Department at the University of Hawaii and has been a visiting professor at several universities. He was the head of research in international affairs for a major U.S. trade union and Assistant General Secretary of an international union federation. His articles have appeared in the Economist Intelligence Unit, Wall Street Journal, WPROST, Pravda and several other news journals. He is the editor and publisher of the web-based news journal of international relations www.ocnus.net.

Lima Charlie provides global news, insight & analysis by military veterans and service members Worldwide.

For up-to-date news, please follow us on twitter at @LimaCharlieNews

SOURCES

[i] https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/html/uscode46a/usc_sec_46a_00000292—-000-notes.html

[ii] 46. U.S.C. § 50101 et seq. (2006).

[iii] Yuen, Stacy (August 22, 2012). “Keeping up with the Jones Act”. Hawaii Business. Retrieved September 12, 2015

[iv] Protecting U.S. Dredgers Kills Jobs,The Foreign Dredge Act of 1906 has stifled competition in the seaport industry., Nancy McLernon, Seatrade, April 16, 2018

[v] ibid.

[vi] ibid.

In case you missed it:

![Image America’s failed seaports - Trump’s ‘America First’ policy isn’t the only barrier to free trade [Lima Charlie News]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/America’s-failed-seaports.jpg)

![Image Tariffs – a mixed blessing for American businesses [Lima Charlie News]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/Tariffs-–-a-mixed-blessing-for-American-businesses-Lima-Charlie-News-480x384.png)

![Image European Union - U.S. trade dispute escalates as E.U. issues retaliatory tariffs on a number of iconic American goods [Lima Charlie News]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/European-Union-U.S.-trade-dispute-escalates-as-E.U.-issues-retaliatory-tariffs-on-a-number-of-iconic-American-goods-480x384.png)

![Image Memorial Day may soon be a remembrance of democracy and those who had the courage to defend it [Lima Charlie News]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/Memorial-Day-may-soon-be-a-remembrance-of-democracy-and-those-who-had-the-courage-to-defend-it-Lima-Charlie-News-480x384.png)

![The Mind of Bolton - AUMF and the New Iran War [Lima Charlie News]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/Inside-the-mind-of-Bolton-Lima-Charlie-News-main-01-480x384.png)

![Image Tariffs – a mixed blessing for American businesses [Lima Charlie News]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/Tariffs-–-a-mixed-blessing-for-American-businesses-Lima-Charlie-News-150x100.png)