North Korea (‘DPRK’) announced it has tested a new ‘hydrogen bomb’ as its sixth test to date in the development of a nuclear program. The DPRK also announced that this new bomb was small enough to be deployed on an intercontinental missile.

Nations of the world have expressed shock and dismay at such a development and have demanded there be a tightening of sanctions against the DPRK and, no doubt, a well-considered resolution of the UN Security Council to make North Koreans aware of the sincerity of the international response. That such measures are largely futile and impotent in the face of DPRK bravado and braggadocio seem to be no deterrent to their acceptance as a realistic response to the new military posture of the DPRK.

Even less credible has been President Trump’s threats of a nuclear strike and the utter destruction of that nation, initially as a first strike response, but later tempered by Secretary of Defense Mattis to be a response to a threat against the U.S. by the DPRK.

The U.S. policy of confrontation is muddled, inchoate and lacking in any coherence. The President has treated all developments as if they occur as some sort of unique event, not understanding that these developments are interlinked to other problems which confront the U.S. and its allies. Each infantile tweet or gut response has its consequence for national policy and the foreign policies of U.S. allies.

The simple truth is that there is no uniform willingness to respond identically to the DPRK’s aggression among the nations of the international community, especially those nearby which share borders or contiguity with the DPRK. These nations (mainly South Korea, China, Japan, Russia and the U.S.) all have much at stake in confronting DPRK aggression. For the rest of the world it is a less urgent problem unless the U.S. decides to escalate its response to the use of nuclear weapons, especially as a first strike response.

The DPRK and its Trading Partners

For many nations of the world the problems posed by the DPRK’s international pariah status are viewed as an opportunity rather than an impediment. For some nations, a close working relationship with the DPRK has been nurtured for a long period.

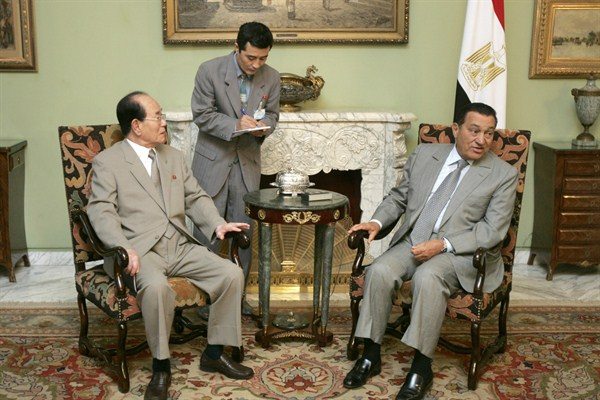

In Egypt, for example, there has been a Cairo-Pyongyang axis growing since the days of Nasser when Kim Il Sung sent financial support for the closing of the Suez Canal by Egypt. The DPRK set up an embassy in Egypt in 1961, and in 1967 offered military and financial support to Egypt in the Six-Day War along with military supplies to help Egypt and its proxies drive the British out of Aden. In the 1973 war against Israel, Egypt’s senior air force commander, Hosni Mubarak, used North Korean pilots to fly missions in Egyptian aircraft. Mubarak made four visits to Pyongyang from 1983-1990 where he laid the foundation for Egyptian investments in the North Korean economy.

According to Samuel Ramani, in The Egypt-North Korea Connection, “The most striking demonstration of Cairo’s willingness to invest in North Korea was Egyptian telecommunications giant Orascom’s establishment of Koryolink, the DPRK’s only 3G mobile phone network, in 2008. This business deal, which was authorized by Egyptian billionaire Naguib Sawiris, gave Orascom 300,000 new North Korean customers. This deal highlighted the potential for mutually beneficial economic links between the two countries, and Sawiris’s subsequent visits to Pyongyang facilitated further Egyptian investments in the North Korean economy.”[i]

North Korea has also been a critical supplier of military technology to Egypt since the 1970s. In 1975, President Anwar el-Sadat authorized the purchase of Soviet-made Scud-B missiles from the DPRK. The North Korean military responded to Cairo’s missile purchase by technologically assisting Egypt’s Scud-B missile production efforts. These missile procurements established long-term technical exchanges between to two nations during the late 1990s and early 2000s. Now, with Iranian progress in producing missiles, Egypt is very anxious to continue to acquire more missile technology from the DPRK which will help it against its main enemy.

Each infantile tweet or gut response has its consequence for national policy and the foreign policies of U.S. allies.

The indelicate Trump tweet offensive against the Iranian 2015 nuclear deal, the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), which may force Iran to drop its participation, has made the acquisition of nuclear technology reappear on the technical military horizons of many Middle Eastern States. Egypt is among them. Despite U.S. and Russian objections, Egypt has not given up hopes to be a nuclear power. Egypt has continued to refuse to accept comprehensive international inspections of its nuclear energy program. This question has been raised by the IAEA’s discovery of highly enriched uranium at Ishas in 2007 and 2008, which occurred despite Mubarak’s rhetorical commitment to a nuclear-free Middle East. Sisi has refused to abandon his close ties with the DPRK and, if the Iranian deal is abandoned, is ready to recommence his own nuclear program.

Egypt is not the only nation in the Middle East with such a fall-back position of engaging with the DPRK if nuclear proliferation becomes an acceptable norm. In 2015 Abu Dhabi purchased USD $100 million worth of weapons from North Korea to use in the war in Yemen (according to a leaked memo from the US State Department.). The deal included a shipment of rockets, machine guns and rifles that were sent to Yemen to support groups loyal to the UAE in the conflict. According to the memo, the US State Department warned Abu Dhabi that North Korea would use the money from its arms deal to finance its nuclear programme.[ii]

The UAE’s covert arms purchases from Pyongyang results from Abu Dhabi’s belief that North Korea is a potentially valuable missile system supplier in the world market and should be deterred from selling sophisticated military technology to Iran and Yemen’s Houthi rebels. As a result of Trump’s inclination to dissolve the JCPOA pact with Iran (which is widely believed to be about to happen) the UAE and other states in the region are preparing for the acquisition of missiles and nuclear technology to counter the expected rush towards competency by Iran, freed of the ICPOA.

North Korea trades with a number of countries which are anxious to retain their link. From 2007 to 2015, the value of annual trade activities between African states and the DPRK amounted to $216.5 million, higher than the average $90 million recorded from 1998 to 2006.

Pyongyang has built arms factories in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Ethiopia, Madagascar and Uganda. It has also been contracted to construct military sites in Namibia. This relationship with Namibia led to Namibia being cited as a violator of UN sanctions. Theoretically, Namibia halted relations with the DPRK in 2016, but Namibian newspapers bemoan the fact that DPRK technicians are still there. Officially, the Namibian Government announced that it had terminated the services of Korea Mining Development Trading Corporation and Mansudae Overseas Projects, but was cunning on the wording for relations between the two countries.

Korea Mining Development Trading Corporation (KOMID), North Korea’s primary arms dealer, is blacklisted under UN sanctions for earning foreign cash through illicit arms trades. Construction company Mansudae is known for having built several state houses, statues and monuments in Africa. In Namibia, they have already built the national history museum and State House, and are busy with the defence headquarters and a shadowy munitions factory. This led to Namibia being accused of violating United Nations sanctions against North Korea. Namibia has already given over N$1,3 billion to North Korea through various construction projects since 2002, and Windhoek seems to remain steadfast in keeping relations with them.[iii]

Police training and leadership-protection courses provided by North Korea have also been popular across the continent, including Benin, Mozambique, Nigeria, and Zimbabwe (best noted for its training of the notorious Fifth Brigade). Pyongyang has also sold ballistic-missile manufacturing lines to Libya, while South Africa intercepted a shipment of weapons from North Korea bound for the Congo in 2009. The ISS reported in Feb. 2016 that Pyongyang was still exporting ballistic missile-related items to the Middle East and Africa.

The DPRK has had a long and profitable relationship with Malaysian traders using the company Glocom, which exports DPRK small arms and communications equipment throughout Central Asia and the Middle East. The DPRK has extensive relations with African countries, especially Equatorial Guinea, Angola, DR Congo, and Burundi. The DPRK’s relationship with DR Congo also recently sparked an international controversy when a UN report was leaked on May 16, 2016 revealing that Congo had purchased pistols from the DPRK in 2014 and recruited 30 North Korean instructors to work alongside the Congolese police and presidential guard.

The DPRK has not been restrained from delivering substantial quantities of chemical and biological weapons to countries around the globe. Of particular interest has been the deliveries of chemical and biological agents to Assad’s Syria (in addition to Scuds and surface to air missiles). In a confidential August 2017 report of UN experts to the Security Council the experts reported the delivery of prohibited chemical, ballistic missile and conventional arms by the DPRK to Syria. The report added that this was because of a log-term contract between Syria and the firm, KOMID.

KOMID is the Korea Mining Development Trading Corporation. It was blacklisted by the Security Council in 2009 and described as Pyongyang’s key arms dealer and exporter of equipment related to ballistic missiles and conventional weapons. In March 2016, the council also blacklisted two KOMID representatives in Syria. “The consignees were Syrian entities designated by the European Union and the United States as front companies for Syria’s Scientific Studies and Research Centre (SSRC), a Syrian entity identified by the Panel as cooperating with KOMID in previous prohibited item transfers,” the UN experts wrote. SSRC has overseen the country’s chemical weapons program since the 1970s.[iv] Although the bulk of DRPRK trade is with China, there are a number of other countries with which it trades less clandestinely.

The DPRK is not a signatory to the international Chemical Weapons Convention. It has been producing chemical weapons since the 1980s and is now estimated to have as many as 5,000 tons.

North Korea and Its Military

The problems which have arisen from the growth of North Korea’s nuclear and missile programs have posed a series of challenges to its neighbours. The most directly affected is South Korea which has a hostile opponent just across its borders with an array of military assets which can destroy Seoul and the hinterland.

These military forces and the missiles and artillery ranged against the South are not easily contained in a conventional attack; even less a nuclear one. South Korea has an existential threat posed by the weaponry of the DPRK which it cannot confront on its own. It relies on the many U.S. troops stationed in South Korea and in the air and sea assets brought to South Korea by the U.S. as a symbol of commitment to South Korea’s survival. However, the fact that the U.S. has an overwhelming power to destroy the DPRK is only a notional security for South Korea as it is only useful as a deterrent to the DPRK. The introduction of several THAAD systems adds to the defensive state of South Korea, but if the deterrent doesn’t work and the DPRK attacks, there is every likelihood that millions of South Koreans will die before the DPRK can be destroyed.

The DPRK is not a signatory to the international Chemical Weapons Convention. It has been producing chemical weapons since the 1980s and is now estimated to have as many as 5,000 tons, according to a biennial South Korean defence white paper. Its stockpile, one of the world’s largest, reportedly has 25 types of agents, including sarin, mustard, tabun and hydrogen cyanide. It also is thought to have nerve agents, such as VX. North Korea also has 12-13 types of biological weapons and can likely produce anthrax, smallpox and plague if war breaks out. North Korea would likely target Seoul’s defences with chemical and biological weapons dropped from aircraft or delivered via missiles, artillery and grenades, experts say.[v]

The new Moon government understands this and is pushing for some form of negotiation to resolve some, if not all, of the tensions. There is probably no human on the face of the planet older than ten years of age who doesn’t know that the U.S. has the overwhelming capacity to destroy the DPRK. The Trump posture of telling the world how many times his military can kill North Koreans is, at the end of the argument, a trivial point. The safety of South Korea depends on the fact of the deterrent (although it hasn’t impeded the DPRK production of nuclear bombs and missiles so far) if it is coupled with some dialogue with the DPRK and economic sanctions which are effective. The point is that the military threat of the DPRK cannot be a problem contained in itself; it must be a part of a wider interaction among the parties.

Trump has consistently returned to the accusation that the solution to the DPRK problem is Chinese policies. He correctly cites the large volume of trade between the two countries and the reliance of the DPRK on China not intervening in the internal affairs of the nation. China has several concerns with the DPRK which temper its ability to shape DPRK policy. One of these is a military problem posed by the DPRK against China and Japan (as well as the U.S. and Republic of Korea fleets); the surprising size and diversity of the DPRK navy.

After the dissolution of the Soviet Union and the reduction in the availability of Russian naval equipment, the DPRK navy (‘KPN’) has developed a range of naval vessels which could prove effective at waging asymmetric warfare at sea. Well-suited to swarming, the Nongo-class fast attack craft, which appears to be 35 metres long and displaces 200 tons, could harass the U.S. and Republic of Korea fleets The Nongo-class is equipped with a turret-mounted 76mm gun, possibly reverse-engineered from the Italian-designed OTO Melara 76mm, along with a complement of Russian-produced Zvezda Kh-35U subsonic anti-ship missiles.

The prominence of submarines in KPN modernization efforts is also telling. Satellite imagery as recent as July 2014 indicates North Korea has built a number of submarines with a length of 65.5 metres and a displacement of between 1,000 and 1,500 tons, which has been dubbed the Sinpo-class, for addition to its East Fleet. The most compelling aspect of KPN asymmetric warfare to date is the continued prevalence of the Yeono-class midget submarines. First introduced in 1965, these vessels require a crew of only two to operate but can carry six or seven passengers, proving useful for DPRK covert operations against South Korea and Japan. With a submerged displacement of 130 tons and a length of approximately 20 metres, each is armed with two 533mm torpedo tubes. [vi]

![Image [Photo: North Korea's Korean Central News Agency (KCNA)]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/Kim-Jong-Un-submarine.jpg)

Of particular concern, North Korea has been making progress toward attaining a nuclear triad by developing a submarine-launched ballistic missile (SLBM) capable of delivering a nuclear warhead. After several failures, the DPRK successfully tested its first SLBM, known as the Pukkuksong-1/KN-11, in late August 2016. With a two-stage solid fuel propellant system, the KN-11 has an estimated range of almost 500 nautical miles, more than enough to threaten major population centres such as Seoul and Tokyo, or military installations like Kadena Airbase in Okinawa, with only limited travel of its launch platform outside of home water. The addition of an SLBM, complemented by a workable launch platform, will greatly enhance the survivability of North Korea’s nuclear delivery capacity and improve the credibility of its nuclear deterrent.

North Korea’s land-based nuclear delivery systems rely heavily on fixed infrastructure and operate in the open, which makes them particularly vulnerable to attack. As a result, even if Trump were to lose ‘strategic patience’ with the DPRK, Pyongyang would likely see its land-based nuclear forces neutralized in a first strike. However, ballistic missile submarines are more survivable than fixed infrastructure because the vastness and depth of the oceans provide concealment within a wide operational area. If the DPRK were to ever lose its land-based nuclear delivery systems in a surprise attack, it would still have the ability to retaliate with an SLBM launch against South Korea or Japan.[vii]

China’s 19th Party Congress

It has been clear for awhile that following a program of “war-mongering” is likely to lead to the isolation of the U.S. and to its embarrassment at not being able to mount a credible response to the DPRK challenges. Trump has, with monumental oversimplification, announced that the U.S. might cut off trade with every country which trades with the DPRK. The realities of the international economic system make such a policy almost as self-destructive as launching a first strike. The U.S. operates in a global environment and cutting off trade with a country like China is almost impossible to achieve; and is certainly not desirable.

China is the major trading partner of the DPRK and has taken some small steps towards enforcing sanctions against the country. The Chinese Communist Party is fast approaching its 19th Party Congress on October 18, 2017. Congresses occur every five years and this one marks the end of Mr. Xi’s first five-year term in office and the start of his second term. Many of the 25 members of the Politburo will be replaced.

This is a crucial period for the government of Xi Jinping, a period in which he has to assert his authority over the party by adhering to its core principles as well continuing his opening-up of the country to its full global potential. Equally as important, Xi Jinping, as head of the CMC military council, has to fulfil his side of the bargain he made with the military to let it reconfigure in return for the PLA removing itself from business.

In January 2016 China announced that it would adopt a radical plan to turn the PLA into a modern fighting force. The CMC stated that there would be a “breakthrough” in the overhaul by 2020, moving away from an army-centric system towards a Western-style joint command in which the army, navy and air force are equally represented. This overhaul of the PLA would phase out its Soviet-style command structures in favour of a US-style model. The seven military command regions will be consolidated into four to help transform the world’s biggest army into a nimble, modern force. Xi said on September 3 the PLA would shed 300,000 troops, leaving it with two million personnel; 170,000 officials would be among the cuts in seven military command regions.

At the 18th Party Congress four years ago, the leadership of Xi Jinping and Li Keqiang was established and an ambitious plan to reform the economy was introduced. The upcoming 19th Congress will carry a similar weight. The new 19th Party Congress is likely to support President Xi’s drive towards modernisation and reform. However, five of the seven members of the Politburo Standing Committee – all except President Xi and Li Keqiang, the prime minister – are expected to step down after reaching the mandatory retirement age of 68 at next year’s Party Congress. This may allow into the leadership some members who appear to wish to proceed more slowly with the relaxation of controls over the economy and the privatisation of the defence industry. President Xi has been trying to bend the rule about compulsory retirement and has sought to keep Wang Qishan (his closest ally) in office after the 19th Congress.

It has been clear for awhile that following a program of “war-mongering” is likely to lead to the isolation of the U.S. and to its embarrassment at not being able to mount a credible response to the DPRK challenges.

The DPRK problem has come at a difficult time for Xi and the Chinese leadership. They were embarrassed at the DPRK nuclear explosion during the BRICS summit hosted by the Chinese at Xiamen. Not only did it steal the thunder of the conference, it put massive pressure on China to “do something” about its supposed client state, the DPRK. Xi doesn’t want this to happen again at the Party conference. He is willing to engage in a range of new sanctions against the DPRK but needs something back to show to the Party leadership.

The PLA has been most upset by the installation of the several THAAD systems in the ROK by the U.S. China is not worried about its missiles being destroyed; it is upset that the sophisticated radar arrays which make up an important part of the THAAD system can observe the activities of the PLAS and the PLN at close distance. The PLA wants these removed or turned off and the Chinese will need some sort of assurance on this in return for concessions on sanctions against the DPRK.

The Russians, too, are interested in controlling U.S. radar capabilities, especially as they can monitor the activities of the Russian Airforce at the Khorol’ AB in the Primor’ye Region, at Mai-Gatka AB, Mongokhta AB, and Kamennyy Roochey AB. Both the Russians and the Chinese have a large number of DPRK workers in their territories and are fearful of the disruption they might cause if an attack on the DPRK takes place.

Both the Russians and the Chinese are willing to pursue stronger sanctions against the DPRK in return for a cessation (or at least a reduction) in the war games which are taking place in and around South Korea and a limit on the introduction of more THAAD systems into the region. What is most important, they say, is that the U.S. engage in a dialogue with the DPRK to see if there is any path to an accommodation of the divergent policies which could lead to a system which would lower tensions in the area. This would be welcomed by Moon of the ROK and by Abe, whose Liberal Democrats in Japan have been lobbying for a constitutional change to allow a more forward use of the previously Self-Defence Force.

If your only tool is a hammer, then all problems look like nails.

This is what is usually called ‘diplomacy’. It involves acquiring knowledge of what the actual situation is; assessing the credibility of the source; analysing the information; examining the effects of any change in policy as it might affect other policies being pursued; and developing a strategy how to go forward. This is what has been missing from the U.S. system. The foreign policy apparatus has been gutted by the Trump administration. Many of the analysts are gone, their desks empty. Trump appears to be missing the ability to see how his ‘policies’ affect other policy priorities. Surely it is not in the U.S. interest to generate further international nuclear proliferation by his attacks on the Iranian deal. His credibility as a person concerned with developing a strategic position with an agreed goal in sight is deficient. The old maxim is still true: “If your only tool is a hammer, then all problems look like nails”.

It is time for an urgent peaceful ‘joined-up’ response to the DPRK problem with a recognition that there are many consequences which arise from any new policy. Sabre-rattling may be fine for the playground but it has no place in a mature democracy.

Dr. Gary K. Busch, for Lima Charlie News

Dr. Busch has had a varied career-as an international trades unionist, an academic, a businessman and a political intelligence consultant. He was a professor and Head of Department at the University of Hawaii and has been a visiting professor at several universities. He was the head of research in international affairs for a major U.S. trade union and Assistant General Secretary of an international union federation. His articles have appeared in the Economist Intelligence Unit, Wall Street Journal, WPROST, Pravda and several other news journals. He is the editor and publisher of the web-based news journal of international relations www.ocnus.net.

Lima Charlie provides global news, insight & analysis by military veterans and service members Worldwide.

For up-to-date news, please follow us on twitter at @LimaCharlieNews

Sources

[i] Samuel Ramani, “The Egypt-North Korea Connection”, Diplomat, August 28, 2017

[ii] Middle East Monitor, “UAE bought weapons from North Korea for war in Yemen” 20/7/17

[iii] The Namibian, “Namibia: Sacrificing Ourselves for North Korea’s Gain”, 1/9/17

[iv] Reuters, “North Korea Caught Sending Two Chemical Arms Shipments to Syria”, Aug 22, 2017

[v] Sarah Gantz, Baltimore Sun, “What chemical weapons N. Korea possesses” 1/5/17

[vi] Paul Pryce , “North Korea and Asymmetric Naval Warfare”, CIMSEC February 15, 2016

[vii] Matthew W. Gamble,”North Korea’s Sea-Based Nuclear Capabilities: An Evolving Threat” CIMSEC 30/5/17

In case you missed it:

![Image What exactly is the extent of Russia’s influence on North Korea? [Lima Charlie News][Photo: Yuri Kadobnov]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/What-exactly-is-the-extent-of-Russia’s-influence-on-North-Korea-1-e1557115659181-480x384.jpg)

![Image Singapore Summit leaves North Korea cyber threat off the table [Lima Charlie News]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/Singapore-Summit-leaves-North-Korea-cyber-threat-off-the-table-Lima-Charlie-News-480x384.png)

![Blossoming Russo-Turkish alliance leaves U.S., NATO behind [Lima Charlie News]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/Russia-Turkey-alliance-leaves-U.S.-NATO-behind-480x384.png)

![Image What exactly is the extent of Russia’s influence on North Korea? [Lima Charlie News][Photo: Yuri Kadobnov]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/What-exactly-is-the-extent-of-Russia’s-influence-on-North-Korea-1-e1557115659181-150x100.jpg)