The General Assembly of the United Nations is meeting in New York to try and resolve the problem of the expulsion of almost 400,000 Rohingya from the Rakhine region of the country by the Myanmar Armed forces (‘Tatmadaw’). The world’s media has been full of condemnation for the repression of this Muslim minority group living in Rakhine, next to the Bangladesh border by the Tatmadaw who have been accused of genocide, ethnic cleansing and crimes against humanity for their actions against the Rohingya. The burning of Rohingya villages and the desperate plight of the refugees fleeing Myanmar are a regular feature of almost every news program.

While these reports and the visual evidence of such violence and repression of the Rohingya cannot be denied or defended, the genesis of this problem must be more fully understood by the world community before it can effectively deal with the Rohingya Question. There has been very little information available to the world community which would allow them to make anything but a knee-jerk moral reaction against the cruelty of the Tatmadaw without understanding the background and conflicts which have created this unfortunate policy.

The question of the Rohingya is bound up with the ethnic politics of Burma; the competing interests of the U.S. and China; the powerful oil and gas industries in Burma which have taken centre-stage in the economy of the country; and the long legacy of the opium trade in the Golden Triangle – with its warlords, international criminal connections and the Air America transport facilities for the opium trade in and out of the Shan States.

The Rohingya are very minor players in the drama of Southeast Asia who have found themselves in the wrong place at the wrong time. They are the collateral damage of the struggle of the larger political and ethnic conflicts in Burma. The old African saying “When the elephants fight it is the grass that suffers” holds true in Burma. The Asian elephants may have smaller ears than the African but they stamp just as heavily.

The Competing Ethnicities of Burma

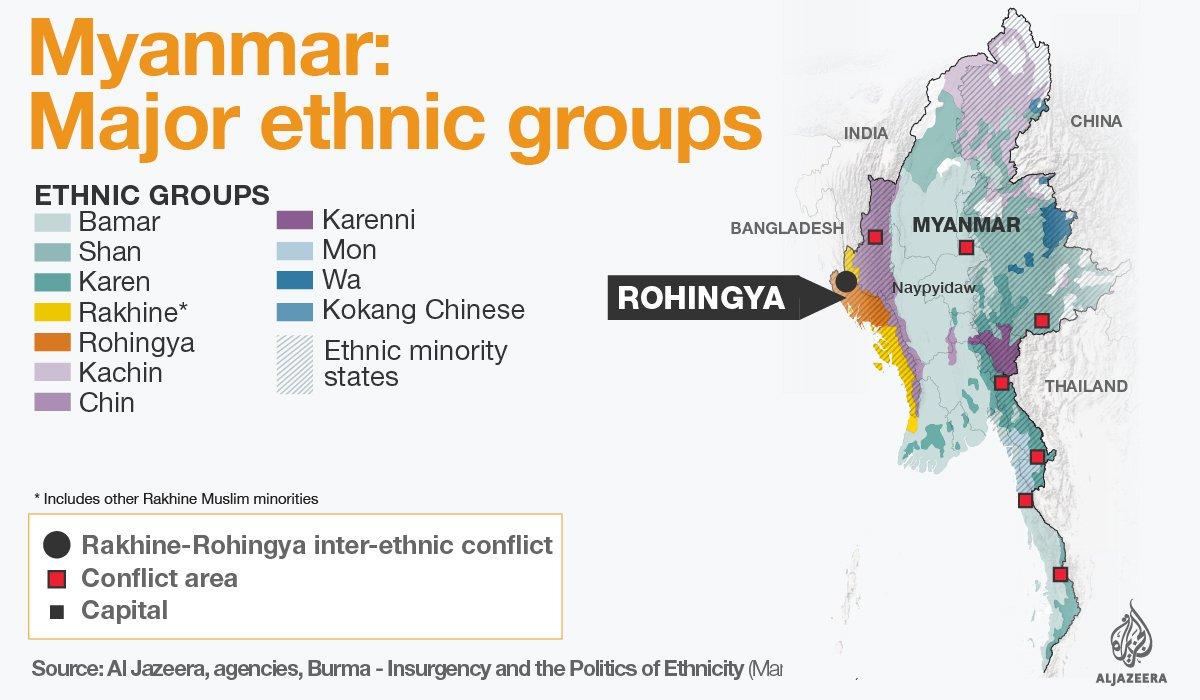

The composition of Burma is an amalgamation of several competing ethnic groups. There are more than 135 different ethnic groups in Burma, each with its own history, culture and language. The majority Burman (Bamar) ethnic group (also known as the Lowland Burmese) makes up about two-thirds of the population and controls the military and the government.

The minority ethnic nationalities, making up the remaining one-third, live mainly in the border areas and hills of Burma. The seven largest minority nationalities are the Chin, the Kachin, the Karenni (sometimes called Kayah), the Karen (sometimes called Kayin), the Mon, the Rakhine, and the Shan. Burma is divided into seven states, each named after these seven ethnic nationalities, and seven regions (formerly called divisions), which are largely inhabited by the Bamar (Burmans). For most of its existence after the end of British colonial rule, these ethnic groups have been at war with the majority Bamar ethnic group and the governments and armies controlled by the Bamar politicians and military.

For centuries, the non-Burman ethnics were enslaved and persecuted by Burman rulers, even after the British asserted their colonial rule over Burma in the mid-1800s. The British used their ‘divide and rule’ colonial policies in Burma. They gave the administrative positions to the Burmans, whose civil service took over many of the tasks of British colonial occupation, but put many of the ethnic leaders in charge of the military. The British staffed two of the four battalions of the regional regiment of the British army exclusively with Karens.

In the period after the First World War, the British began to reduce their direct control over Burma in the face of Burman nationalism and allowed the Burmans to take more effective control of the country. By 1920 the British allowed a period of ‘home rule’ and Burma became a “ministerial” government under Westminster’s ultimate authority, with a Burman prime minister, a Burman cabinet, and a legislature dominated by Burman nationalist parties. (1) Its rallying cry was “Burma for the Burmans!”

A consequence of this Burman nationalism was the concomitant rise of ethnic identity among the minority groups who formed their own militias and armies, although the Karen remained a powerful force in the national army. This lasted until the opening of the Second World War when the military forces of the Japanese Empire expanded its “Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere” to South East Asia. Many South East Asian nationalist leaders were attracted by the notion of escaping from British, French and Dutch colonial rule by taking the side of Japan in its struggle to expand its empire.

Just as the Indian nationalists formed the Indian National Army (‘INA’) under Mohan Singh and Subhas Chandra Bose in 1942 to fight the British with the assistance of the Japanese, other Asians followed the Sane path. In Burma, a Burman group of “Thirty Comrades” formed the Burmese Independence Army under the leadership of General Aung San. Aung San had been secretary of the students’ union at Rangoon University and, with U Nu, led the students’ strike there in February 1936. Aung San worked for the nationalist Dobama Asiayone (“We-Burmans Association” or “Our Burma Association”), becoming its secretary-general in 1939.

In that capacity, he was contacted by the Kempei Tai (Japanese Secret Police) and the Japanese Army and agreed that the Japanese would fund the creation of a Burmese army to drive out the British. He formed the Burma Independence Army, which fought alongside the Japanese in Burma and often employed genocidal tactics, targeting Karen civilians and brutally massacring the inhabitants of hundreds of Karen villages. Meanwhile, the Karen fought on behalf of the British, staging what some have called the Second World War’s most successful guerrilla operation against the Japanese forces.

The Japanese formed a puppet government in Burma under Ba Maw in 1943 and General Aung San became the minister of defence. However, when it became clear that the Allies were winning the war, Aung San switched his army’s loyalties. He agreed to use his Burma Independence Army to support the British and drive out the remaining Japanese. The British agreed and General Aung San began to attack Karen villages. He became a Burmese national hero and his daughter Aung San Suu Kyi (‘Daw Suu’) became a famous politician in her own right, winning the Nobel Prize.

The triumph of General Aung San was guaranteed and his first order of business was to purge the Burmese Army of any ‘ethnics’. He drove out all the minorities and created a ‘pure’ Burman military machine to run Burma. The ethnic minorities began to form their own armies for self-defence and complained to Britain, In 1947. General Aung San went to London to meet with Attlee to discuss reducing the tension in the country. Churchill made his famous comment on the Burmese hero “I certainly did not expect to see U Aung San, whose hands were dyed with British blood and loyal Burmese blood marching up the steps of Buckingham Palace as the plenipotentiary of the Burmese Government.”

General Aung San made some dilatory promises of allowing a federal system to develop in Burma. These asides were sufficient to enrage his comrades and General Aung San was assassinated on July 19, 1947 to be replaced by his old comrade U Nu who became Burma’s first Prime Minister when the country gained independence in 1948. U Nu became a famous democrat and statesman, revered for his wisdom and dedication to peace despite a bloody and violent campaign of “Burmanisation”. The nearly exclusively Burman ministries proselytized Buddhism in the countryside, promoted the teaching of history from a perspective of Burman nationalism, passed acts stripping “foreigners” of entitlements to their property, and mandated that only Burmese (the Burman language) be used in governmental affairs and taught in schools from the fourth standard onward.

In February 1948, the Karens staged a peaceful nationwide demonstration of over 400,000 people, expressing their desire to avoid civil war and calling for an end to violence, equity among all ethnic groups, and the immediate creation of a Karen state.” Acting in solidarity with the ethnic Mon, Karen leadership approached U Nu, demanding a separate Karen-Mon state. The government responded by supplying Burman irregulars with weapons (some 480,000 rounds of ammunition in just a month). Those irregulars proceeded to fire on Karen neighbourhoods unprovoked. Then, on Christmas Eve in 1948, while the congregated inhabitants of two Karen villages were singing carols at midnight, the Burman policemen who had disarmed them launched hand grenades into their church, fired on the survivors, and torched every last structure.”

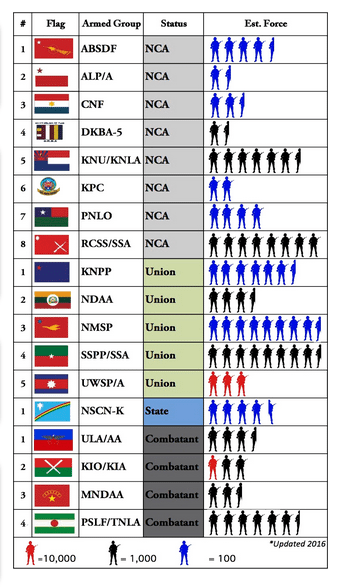

Under U Nu the ethnic groups formed their own self-defence armies. There have been many ceasefires, temporary truces and re-organisations but the wars have continued in one form or another.

After three successive parliamentary governments the Tatmadaw, led by General Ne Win, made a coup d’état in 1962, which ousted the parliamentary government and replaced it with a military junta. With the military takeover of the government human rights abuses and violations were common. The political leaders of ethnic minority groups were arrested and detained without trial. This polarised the situation and the ethnics formed larger and more powerful rebel factions. Some, like the Kachin Independence Army, demanded the formation of a federal government which would enable local autonomy for the ethnic groups. Ne Win refused. A long series of wars by the Tatmadaw against the ‘ethnics’ began and has never ceased.

In 1963, the Burmese military started using the so called ‘Four Cuts’ strategy, intended to suppress support from ethnic communities for ethnic opposition armies by cutting off the four main links between them; food, funds, intelligence and recruits. The Four Cuts policy operated by terrorising the civilian populations in zones where ethnic nationality armies operate. This abuse was designed to instil fear in the civilian population in an attempt to prevent the possibility that civilian communities would provide any kind of support to the armed groups. In order to cut support from rural villagers to ethnic armies, the Burmese military began relocating, attacking and destroying villages, as well as killing and/or torturing everyone suspected of aiding the opposition groups. Large areas became ‘free-fire’ zones (contested areas also called ‘brown’ zones), and entire communities were forced to move to fenced areas subjected to tight military control. Anyone trying to remain in their homes was shot on sight.

There were also many reports of the Burmese military routinely torturing and raping civilians suspected of supporting the ethnic armies. The Four Cuts policy led to thousands of civilian deaths and the destruction of food, crops, and numerous villages. Tens of thousands of communities were destroyed by Four Cuts operations. What is now happening to the Rohingya is part of a long tradition of Burmese politics. The Burmese borderlands on almost its entire periphery are filled with refugees from the tender mercies of the Tatmadaw. (3)

Burma And Its Neighbors

Burma is located in a geographical area which has been a source of major conflict since the 1960s.

One of the first pressures on Burma was the 1967 Cultural Revolution in China when violence broke out between local Bamars and overseas Chinese in Myanmar leading to anti-Chinese riots in Rangoon (now Yangon) and other cities. The riots left many overseas Chinese dead, which prompted China to begin giving logistical aid to the Communist Party of Burma (CPB) in 1968. Ethnic forces in Burma which were dependent on China for assistance began getting large supplies of weapons, training and safe havens on the Chinese border under General Ne Win’s twenty-six-year dictatorship. Burma became an isolated hermit kingdom and one of the least developed countries in the world.

In 1988, nationwide student protests resulted in the BSPP and General Ne Win being ousted and replaced with a new military regime, the State Peace and Development Council. This began a long period of direct Chinese involvement with Burma; first as a source of conflict over the rights of Chinese in Burma, and later, as a major economic force in the Burmese economy.

By far the greatest influence on Burma has been the politics of opium and heroin from the Golden Triangle. This zone is located at the border of Burma, Thailand and Laos and has been one of the major sources of opium since the 1950s.

At the end of the Second World War the Chinese Nationalist forces of the Kuomintang (‘KMT’) were driven out of Yunnan Province by the People’s Liberation Army (‘PLA’) and returned to Taiwan. The PLA shut down the cultivation of the opium poppy in Yunnan. However, several elements of the KMT remained in Thailand and the Burmese Shan states (mainly the remnants of the 997th Brigade). They settled down in the Golden Triangle and expanded the cultivation of the opium poppy there.

Later, in the early 1960s, additional KMT troops entered Thailand and were divided into three main groups. The KMT 5th Army, numbering just under 2,000 men and commanded by General Tuan Shi-wen, established an armed camp on Doi Mae Salong close by the Burmese frontier in Chiang Rai Province. The KMT 3rd Army, numbering around 1,500 men under the command of General Li Wen-huan, made its headquarters at the remote and inaccessible settlement of Tam Ngop, in the farthest reaches of Chiang Mai Province. Finally, a smaller force of about 500 men, the KMT 1st Independent Unit under General Ma Ching-kuo, acted as a link between the two main factions, reporting directly to Taiwan.

By this time the war in Vietnam had started and South-East Asia was host to U.S. advisors and trainers of local forces, both the ARVN and the Montagnards. These numbers grew. As the Viet Cong developed the Ho Chih Minh Trail as a supply route south via the Laotian border the U.S. created the Raven Forward Air Controllers (the ‘Steve Canyon Program’) at Long Thieng home base of Laotian Hmong leader, General Vane Pao. There was a desperate need to supply these bases in the Golden Triangle with food, medicines and ammunition. The U.S. created its own airline, Air America, which would act as a delivery service to and from the Golden Triangle (mainly Long Thieng, Siam Reap, Chiang Mai and Chiang Rai). They flew in full and had to fly back empty so it was agreed that Air America would fly back the local produce to an eager market. They flew back with planeloads of opium base, and later heroin. The late president of Vietnam, Nguyen Cao Ky was a pilot on the route for a while. By 1971 there were seven heroin factories, located at Ban Huei Sai, Laos.(4)

The development of the heroin business to Burma was very important because the Shan states and some adjoining ethnic regions, suddenly had massive financial flows from the trade which they used to buy weapons. The most important of these was the 1) army of the Shan drug lord Khun Sa; 2) the Shan United Army (SUA); 3) the Kuomintang (KMT, remnants of the nationalist Chinese force that battled Mao’s Communists); 4) and the Wa (a tribe of former head hunters); and 5) the eastern Shan State army (a group of Kokang Chinese).

Burmese drug trafficking is now primarily controlled by the United Wa State Army, one of the world’s largest and most powerful drug militias. According to Jane’s Défense Weekly, it has 20,000 troops and is heavily armed with surface-to-air missiles.

The most famous of these Shan States warlords was Khun Sa. He was dubbed the “Opium King” in Burma and was the commander-in-chief of the MongTai Army from 1985 to 1996 and the Shan United Revolutionary Army after 1996. Another famous Burmese drug lord was a woman, Olive Yang, the royal-turned-warlord, whose CIA-supplied army consolidated opium trade routes in the Golden Triangle in the 1950s. She was the tomboy daughter to the hereditary royal ruler of the Shan state of Kokang and, in addition to the opium business, she served as a government peace broker with Kokang rebels.

The Burmese drug trafficking didn’t stop with the death of Khun Sa. It is now primarily controlled by the United Wa State Army; one of the world’s largest and most powerful drug militias. According to Jane’s Défense Weekly, the United Wa State Army has 20,000 troops and is heavily armed with surface-to-air missiles. They have traditionally been based in Pang Hsang, Myanmar. The group is also considered the region’s largest drug-dealing organization. Some analysts estimate the UWSA is made up of 30,000 full and part-time fighters. UWSA chairman Bao Yu-xiang operates out of the UWSA headquarters in Panghsang in Shan State in northern Myanmar. The US State Department has called the UWSA the world’s largest drug-trafficking army. They also deal in amphetamines.

What is important about the Burmese Government and the Golden Triangle is that the international drug trade is largely out of their control and in the hands of the ethnics. The Tatmadaw have been waging endless wars with the various ethnic armies and have made a series of ‘peace deals’ with the ethnics which have always lasted a very short time. Nonetheless there are constant scenes of Karens, Kachins and others being driven out of their homes and left as refugees along the Thai border when the Tatmadaw attacks. These divisive policies toward the ethnic nationalities persisted even after Thein Sein’s assumption of Burma’s presidency in 2011 and his cosmetic “liberalisation” of Burmese politics which allowed Daw Suu to take over official control of Burma in 2015.

A lot of this conflict has been reducing and the tensions lowered. This has not been because the Tatmadaw is any less rabid about Buddhist nationalism or willing to adopt federalism; still less is it an attack of democracy after the recent election of Daw Suu and her party to power. Change in Burma has been happening as the result of massive international investment in Burma by the Chinese and the French which has created prosperity for the Burmese establishment.

The Crucial Role of China in Burma

In January 1982, Deng Xiaoping articulated the 16-character “Military-Civilian Combination Policy” (“military-civilian unity, peacetime-wartime unity, priority for military production, use civilian production to support the military.”). As a result, many of the regions and bureaus of the PLA began to form companies of their own. The Chengdu Military Region incorporated, in its Southern Area, the province of Yunnan which was the operating base for the three major heroin trading Triad Families: the 14K Triad, which included twenty subgroups; the Wo group, which included twelve factions, including Wo Shing Wo, and Wo On Lo; and the Teochiu Societies, which included six subdivisions, of which San Yee On was the biggest and best known. The Chinese Triads were the logistical arm of the Golden Triangle opium/heroin trade that was not carried on Air America. The first business with Burma (and Thailand and Laos) was the drug business.

As the Chinese economy grew and the reforms of the economic model took place, the emphasis of Chinese interest in Burma moved to a more ‘normal’ economic interaction. The Chinese began to build rail links through Burma.

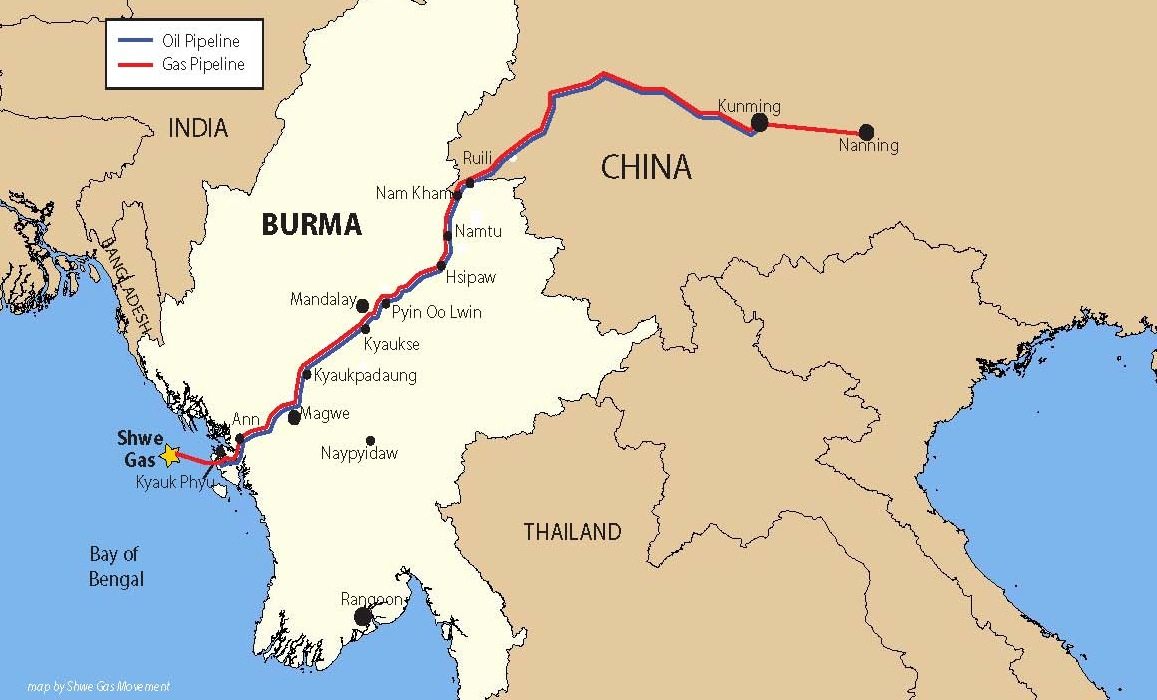

As Total began to expand its oil and gas discoveries off the Rakhine Region (or ‘Arakan’), the Chinese built a long oil and gas pipeline to link that production with China and Northern Thailand. The Yadana gas field, located in the Andaman Sea approximately 60 kilometres offshore, was discovered by state-owned Myanmar Oil and Gas Enterprise (MOGE) in 1982. As Myanmar’s oil industry was still closed to foreign investment at the time, MOGE lacked the technical and financial resources to develop it. That changed in the late 1980s, when Myanmar decided to call on international companies to develop its hydrocarbon resources. Total was selected and set up Total E&P Myanmar.

Production began in 1998 after three and a half years of work and a significant amount of investment. Today, a new pipeline to Yangon ensures that a quarter of production, or around 2 billion cubic meters a year, is supplied to Myanmar’s domestic market, with the remainder exported to Thailand. In 2014, further large-scale works began on Blocks M5 and M6 of the Yadana complex with the aim of developing the Badamyar field and installing an additional compression platform. This will allow the Yadana consortium to maintain plateau production until well after 2020. On January 4th, 2016, a gas discovery was announced with the drilling of the deep offshore (2000m) well Shwe Yee Htun.

Total announced in July 2017 that it will build a power plant in Burma using its natural gas. Total sold about 11 million tons of LNG last year and is seeking to expand its footprint in downstream activities like regasification terminals, pipelines and power plants to help create new gas demand as it refocuses away from oil. (5)

There are a number of oil and gas projects underway in Burma. These projects are a great source of income to the Burmese generals. The Burmese military junta has earned almost $5bn from a controversial gas pipeline operated by the French oil giant Total and deprived the country of vital income by depositing almost all the money in bank accounts in Singapore. Campaigners say Total has also profited handsomely from the arrangement, with an estimated income of $483m from the project since 2000. Campaigners say that the windfall from the Yadana pipeline, operated by Total and two other partners, has been so huge that it has done much to insulate the country’s military rulers from the impact of international sanctions imposed over its human rights abuses.

The pipeline in eastern Burma, which carries gas from rich fields in the Andaman Sea through Burma and into Thailand, has long been controversial. Campaigners have regularly claimed that the authorities have used forced labour in the project, security for which is provided by the Burmese armed forces.

According to a confidential IMF report, Burma’s natural gas revenue “contributed less than 1 per cent of total budget revenue in 2007/08, but would have contributed about 57 per cent if valued at the market exchange rate”. The report says that at these rates, the regime has listed just $29m of its earnings while around $4.8bn is unaccounted for. The military elite are hiding billions of dollars of the people’s revenue in Singapore while the country needlessly suffers under the lowest social spending in Asia. (6)

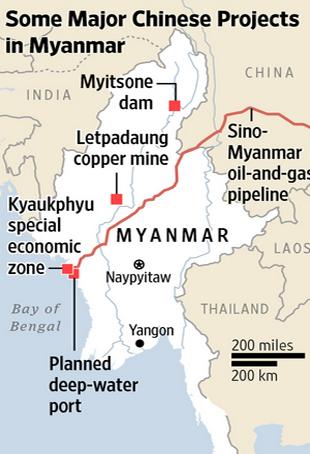

China is heavily involved in a wide variety of investments in Burma.

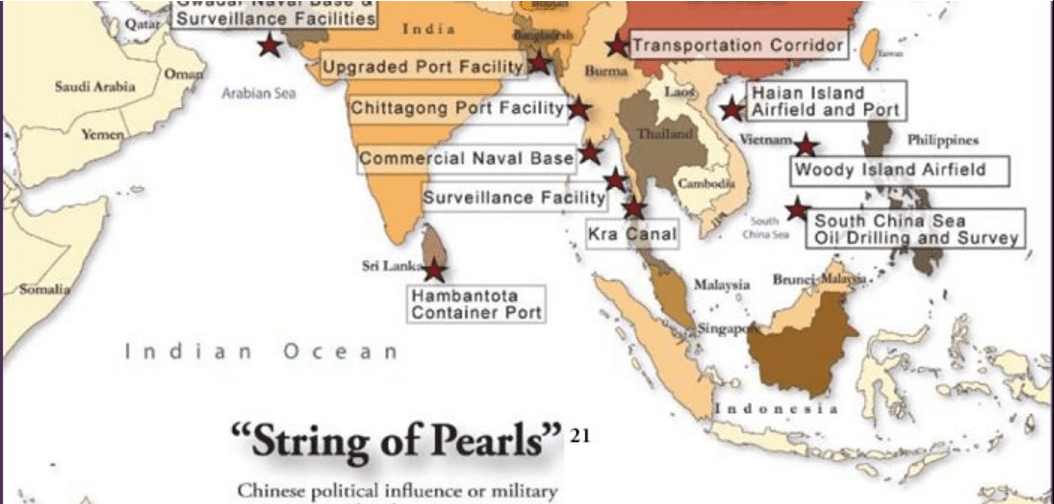

One of the most important of these investments is the building of new deep-water port on the Bay of Bengal as part of China’s “One Belt, One Road” new trade policy to recreate the old Silk Route. China is building a “String of Pearls in pursuit of this and Burma plays an important role.

The military elite are hiding billions of dollars of the people’s revenue in Singapore while the country needlessly suffers under the lowest social spending in Asia.

China has a deep financial interest in pursuing its economic interests in Burma, especially with the oil and gas sources and the new port and marine surveillance facility it is building in Rakhine. Unfortunately, these two are in the area in which the Rohingya live.

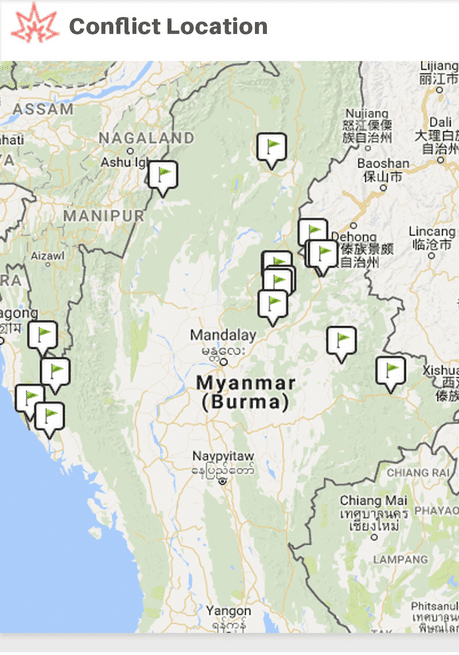

The territory of Rakhine is also the site where there is a new ethnic military force which doesn’t include the Rohingya. On March 29, 2015, the Tatmadaw was caught off-guard when it was assaulted and overrun in two separate locations: Kyauk Taw, in northern Rakhine State, and Paletwa, slightly north of Kyauk Taw in neighbouring Chin State. In Kyauk Taw, two soldiers were killed, and two were taken prisoner; in Paletwa, a captain was killed, a private was injured, and two soldiers were taken prisoner.

As surprising as the assault was, more surprising was the group behind it: a relatively obscure militia called the Arakan Army, using the former name of Rakhine State. This group had previously only been known for operating in the country’s northern Kachin and Shan States, mostly in a supportive position of the much better-known Kachin Independence Army. In a single carefully coordinated attack, though, the Arakan Army has gone from obscurity to prominence. The commander of the Arakan Army, Brigadier General Tun Myat Naing is younger than his contemporaries of the other ethnic armed groups in the country.

The Arakan Army (AA) was formed in 2009 in the Kachin Independence Army (KIA) stronghold of Laiza, on Myanmar’s northern border with China, where the Arakan ethnic rebels received training and arms. They have fought alongside the KIA, the Ta’ang National Liberation Army (TNLA) and Kokang’s Myanmar National Democratic Alliance (MNDAA) in Kachin and Shan states. Around the time of the clashes in Rakhine State, heavy fighting broke out in the country’s semi-autonomous Kokang Region on the Chinese border, and clashes intensified between the Tatmadaw and the Kachin Independence Army. This was done in co-ordination with the AA.

The Tatmadaw conducted raids and arrested a number of Rakhine citizens it suspected of being associated with the Arakan Army. Their food was taken by the army. People were treated badly, beaten and tied up, hanging under trees. A village was completely burnt down by some Burmese soldiers. The AA has now become the major insurgent for in Rakhine.

However, the ethnic military conflict in Rakhine is not only being undertaken by the AA. In the 1970s Rohingya Islamist movements began to emerge from remnants of the Rohingya mujahideen (introduced into Rakhine by the U.S. and India), and the fighting culminated with the Burmese government launching a massive military operation named Operation King Dragon in 1978. In the 1990s, the well-armed Rohingya Solidarity Organisation was the main perpetrator of attacks on Burmese authorities near the Myanmar–Bangladesh border.

In October 2016, clashes erupted on the Myanmar–Bangladesh border between government security forces and a new insurgent group, the Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army (‘ARSA’ or Harakah al-Yaqin), resulting in the deaths of at least 40 people (excluding civilians). It was the first major resurgence of the conflict since 2001. In November 2016, violence erupted again, bringing the death toll to 134. During the early hours of 25 August 2017, up to 150 ARSA insurgents launched coordinated attacks on 24 police posts and the 552nd Light Infantry Battalion army base in Rakhine State, leaving 71 dead (12 security personnel and 59 insurgents). It was the first major attack by Rohingya insurgents since November 2016. (7)

The Tatmadaw attacked scores of Rohingya villages in retaliation and led to the current situation of 400,000 refugees in Bangladesh. The fundamental problem for the Rohingya is that there is another, more powerful, ethnic Burmese army claiming Rakhine as its home territory, the AA. They have no love for the Rohingya and the Tatmadaw will certainly not protect them.

The situation is difficult for the Rohingya. The Chinese want, and need, to protect the new port it is building in Rakhine as well as its Special Free Trade Zone. Total and the Burmese Government rely on the oil and gas from the onshore and offshore installations in Rakhine as well as the rail and road links. The AA are in close contact with the PLA through the Kachin Army and the Kohang groups. The Chinese want to use these ethnics, the AA, as a foil against the Burmese generals in the pursuit of the Chinese economic plans for the country. The Chinese can turn up the heat on the Tatmadaw through the ethnic forces, including the AA. There is no room for the Rohingya in that equation. They are in the wrong place at the wrong time.

The role of the international community is more complicated. In 2012, when it looked as if there might be an outbreak of democracy in the country, President Obama met with Thein Sein (the new head of the Tatmadaw) who made 11 commitments to implement additional democratic reforms and human rights protections. The 2015 elections made some major, if cosmetic, changes to how Burma was ruled. The Tatmadaw retained a 25% hold of the seats in the Parliament but allowed civilian rule. Encouraged by this, the U.S. sent a Congressional delegation to Burma to pursue a policy of restraining the Tatmadaw from further wars on the ethnics and the Rohingya.

The U.S. was trying, along with India, to propose a policy that would lead towards a more restrained grasp of power by China. In that, Thein Sein and the generals foresaw this as strengthening their hand against the Chinese. The Tatmadaw did very little to fulfil its pledges to Obama and the U.S. withdrew its support as the Tatmadaw pursued its wars against the ethnics and the destruction of the Rohingya. Trump has turned his back on Burma and left it to the Chinese. The Tatmadaw have nowhere else to go but the Chinese. The Chinese have supported Burma in its current suppression of the Rohingya.

Conclusion

It is very difficult to say if anything can be done to support the Rohingya. It is clear that the Burman Buddhists are fully behind the policy of hostility, a situation which puts Daw Suu in a bind. If she speaks out against the Tatmadaw policies she, and her party, will lose influence at home. It is a bit hypocritical for the Western powers to bemoan the fate of the Rohingya when they have, for so many years, ignored the plight of the other ethnic victims of the Tatmadaw; including many Christians who have been slaughtered and oppressed. Injustice doesn’t always prevail but it tends to be more resilient than the pious wishes of peace and democracy.

Dr. Gary K. Busch, for Lima Charlie News

Dr. Busch has had a varied career-as an international trades unionist, an academic, a businessman and a political intelligence consultant. He was a professor and Head of Department at the University of Hawaii and has been a visiting professor at several universities. He was the head of research in international affairs for a major U.S. trade union and Assistant General Secretary of an international union federation. His articles have appeared in the Economist Intelligence Unit, Wall Street Journal, WPROST, Pravda and several other news journals. He is the editor and publisher of the web-based news journal of international relations www.ocnus.net.

[Title image by Dan Kitwood at Getty Images]

Lima Charlie provides global news, insight & analysis by military veterans and service members Worldwide.

For up-to-date news, please follow us on twitter at @LimaCharlieNews

Sources

- Charmaine Craig ,”Burma’s Fault Lines: Ethnic Federalism and the Road to Peace”, Dissent Fall 2014

- Ibid.

- http://www.burmalink.org/background/burma/dynamics-of-ethnic-conflict/overview/

- Alfred W. McCoy, “The Politics of Heroin in South-East Asia”, Harper & Row, NY 1972 p.246

- Kyaw Thu, “Total in Talks with Myanmar to Build Power Plant, Supply LNG”, July 20, 2017

- http://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/asia/burmese-generals-pocket-5bn-from-total-oil-deal-1784497.html

- BBC News, “Myanmar tensions: Dozens dead in Rakhine militant attack” 25 August 2017.

![Blossoming Russo-Turkish alliance leaves U.S., NATO behind [Lima Charlie News]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/Russia-Turkey-alliance-leaves-U.S.-NATO-behind-480x384.png)