Colombia’s political swing to the far right may be helping drive investment to its emerging markets, but at the risk of continuing the violence which has marred the country’s history.

In the past two years coca production in Colombia has increased by 50%, and in the areas where the drug is produced, assassinations of local political activists are escalating even faster. Last year alone saw an increase of 45%.

The assassinations are predominantly in areas that had been at war from 1964 up until 2016, when FARC rebels and the government signed a groundbreaking peace accord. President Juan Manuel Santos received a Nobel Peace Prize for his efforts bringing the conflict to a close, and the country poured out its enthusiasm for the end of the civil strife.

However, just two years later, Santos is leaving office with approval ratings below 14%. Although his popularity increased after the peace deal, Santos suffered a significant drop in popularity after revelations about corruption. In March 2017, he admitted to taking illegal campaign contributions from the Brazilian conglomerate Odebrecht. Following the release of the Paradise Papers it was also revealed that he had controlled two companies based in Barbados to avoid taxes.

The apparent corruption didn’t play well with the Colombian people, especially given the dire economic straits of the country. In 2014, Colombia lost $90bn (around 24%) of its GDP, in large part due to a global crash in the prices of fuel and commodities, which comprised a large portion of the country’s exports.

Compounding these woes, for those living in former war zones, the country’s economic troubles have meant that the central government has neglected to fill the power vacuum left by the armed groups.

“The territories FARC controlled are left with no authorities,” a filmmaker working in the area told the Atlantic. “The Colombian state never had a presence in many of those areas. And so in Cauca [in the Colombian countryside] alone, there are a reported 12 different armed groups now operating, mainly as narco-trafficking organizations.”

Since the economic crisis, Santos brought a series of austerity measures and tax hikes that have helped the government’s balance sheets, but not his own popularity. A 2016 3% sales tax hike was particularly damaging. Repeated attempts by Santos to cut costs accruing from the country’s universal healthcare program and funding for education have cost him popularity, and have proven difficult to implement in the face of the Colombian constitution’s guarantee to protect the health of all citizens.

The President’s unpopularity has driven a knife through the heart of the establishment’s electoral chances.

Santos is a thoroughbred of Colombia’s political class — his lineage traces back to the country’s founding and his family tree is littered with with elected officials and newspaper publishers from the 20th century. The consequences of the national mood have been an electoral disaster for Santos’ Party of Unity, whose candidate received just 7% of the vote in the first round of the presidential election.

The Far Left and Far Right Emergence

It’s not just the party of Santos that lost face. The Colombian government has been led by a coalition of center left and right parties for some time now, but parliamentary elections in March disempowered that coalition. Emerging from the ashes of Santos’ political legacy were representatives of the far-left and the far-right.

From the right, Iván Duque is the political protege of Santos’ presidential predecessor, Álvaro Uribe. The revocation of Santos’ tax hike is his primary economic talking point. On the left, Gustavo Petro, a former mayor of Bogotá who turned to politics after a career as a paramilitary rebel, is running on promises to increase healthcare and education spending.

“The FARC got a better deal than their victims, and I’m the one who will right this injustice,” Duque said in a speech in Bogotá. Notably, in a popular vote referendum held several months after the deal was struck, 50.2% voted against it.

Duque has promised to modify Santos’ peace deal, an implicit return to the policies of former-president Uribe. Uribe’s term as president was marked by collaboration with right wing paramilitaries and U.S. drug enforcement efforts to crush rebels and drug dealers in the countryside. Thousands were killed in the violence, resulting in a recent Supreme Court investigation into Uribe’s alleged intimate ties to drug traffickers and death squads, and role in the formation of anti-communist paramilitary groups that murdered and displaced even more civilians than all guerrilla groups combined.

Petro’s support is strongest in urban areas like the nation’s capital, among the Afro-Colombian Minority, and with campesinos (peasant farmers). Political organizing campesinos are the primary victims of the rural assassinations.

However, with 10 days to go until the election, conventional wisdom holds Duque’s victory as a fait accompli.

In the first round, Duque received 39%, which wasn’t quite enough to clinch it. The turning point was when the 3rd runner up in the first round, Sergio Fajardo, a former mayor and governor, announced that he will not be casting a vote in the upcoming elections. This decision is expected to split his supporters between Duque and Petro, leaving Petro with a 2.7 million vote gap to clear. As of this writing it appears that Duque’s message is winning.

And the international response?

International trading in the Colombian currency is booming, as investors salivate over Duque’s pro-business outlook, promises to cut taxes, a rebounding oil market, and Colombia’s fiscal solvency. According to Marketwatch, “emerging-market bulls are taking notice of Colombia, hailing it as a rising star and forecasting its currency will be a world beater in 2018.”

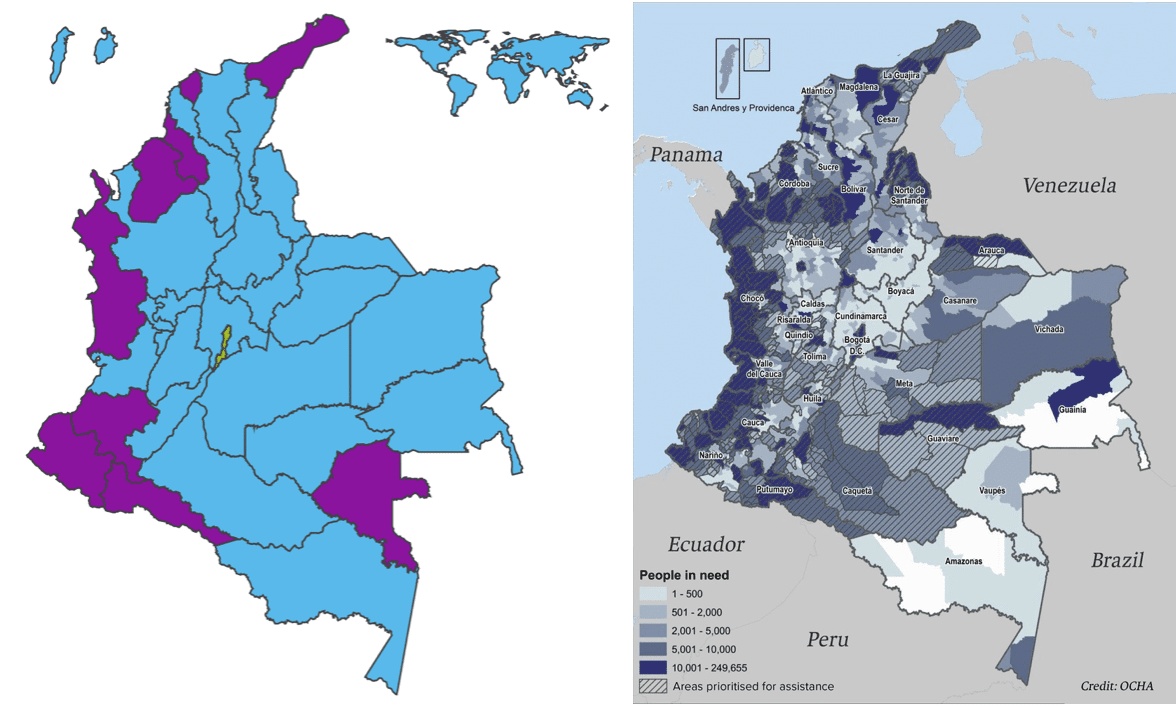

[Left: Results of the first round (green for Fajardo, blue for Duque, purple for Petro). Fajardo’s green sliver is the capital Bogota. Right: UN estimates of the number of people in need of humanitarian assistance as a result of the civil war. On June 5, the Colombian Agricultural Society announced its support for Duque. Support from this business group reflects favor from those who stand to benefit from the development of the country’s agricultural inland.]

Yet, Colombia’s difficulty in maintaining peace in the rural areas is consistent with its history.

Following the death of founding father Simon Bolivar, the country was split between conservative and liberal factions, turning 1840-1903 into an “Epoch of Civil Wars.” This ended with the “War of 1000 Days,” a clash sparked in coffee growing regions suffering from a global downturn in the price of coffee. From 1948 to 1958, the Colombian Conservative Party and the Colombian Liberal Party waged a horrific civil war called “La Violencia” mainly in the countryside, resulting in the deaths of at least 200,000 people. The conflict was incited after a newly elected conservative government used the military and police to repress the Liberal party, which in turn mobilized campesinos to fight back against the government. After a couple of administration turn-overs, fighting took place between a number of guerrilla groups made up of campesinos on both sides of the political spectrum.

The FARC deal ended a 50 year conflict that claimed over 220,000 lives with almost 7 million internally displaced.

While Duque’s election may be good news for attracting international investment, his promise to overhaul the peace deal may slide Colombia backwards towards a more violent past.

LIMA CHARLIE NEWS, with Diego Lynch

[Editor’s Note: The following was added to the article on June 9, 2018: “Notably, in a popular vote referendum held several months after the deal was struck, 50.2% voted against it.”]

[Title Image: FARC members attending the September 17-23 National Guerrilla Conference in Caqueta department, Colombia, on September 17, 2016, just prior to the peace deal. (AFP Photo/Luis Acosta)]

Lima Charlie provides global news, insight & analysis by military veterans and service members Worldwide.

For up-to-date news, please follow us on twitter at @LimaCharlieNews

In case you missed it:

![Image As Colombia’s economy moves forward, its history may slide backwards [Lima Charlie News] (Photo: Luis Acosta / AFP]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/title.jpg)

![Image The rise and dominance of Colombia's private military contractors [Lima Charlie News]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/Colombias-Private-Military-Contractors-Lima-Charlie-News-480x384.png)

![Image NATO's embrace of Colombia signals Western insecurities about China in Latin America [Lima Charlie News][Photo: Mauricio Duenas Castaneda / EPA]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/NATOs-embrace-of-Colombia-signals-Western-insecurities-about-China-in-Latin-America-480x384.jpg)

![Image This Week in Business Intelligence [Lima Charlie News]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/This-Week-in-Business-Intelligence-Lima-Charlie-Business-Intel-Report-480x384.png)

![Image Memorial Day may soon be a remembrance of democracy and those who had the courage to defend it [Lima Charlie News]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/Memorial-Day-may-soon-be-a-remembrance-of-democracy-and-those-who-had-the-courage-to-defend-it-Lima-Charlie-News-480x384.png)

![The Mind of Bolton - AUMF and the New Iran War [Lima Charlie News]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/Inside-the-mind-of-Bolton-Lima-Charlie-News-main-01-480x384.png)

![Image The rise and dominance of Colombia's private military contractors [Lima Charlie News]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/Colombias-Private-Military-Contractors-Lima-Charlie-News-150x100.png)

![Image NATO's embrace of Colombia signals Western insecurities about China in Latin America [Lima Charlie News][Photo: Mauricio Duenas Castaneda / EPA]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/NATOs-embrace-of-Colombia-signals-Western-insecurities-about-China-in-Latin-America-150x100.jpg)