Human suffering scales efficiently when it is managed.

The weaponisation of refugees is a low-cost, high-leverage instrument for states able to tolerate ambiguity and export instability. Public vocabulary treats refugees as a humanitarian outcome. In practice, they are an operational resource. In modern conflict, displacement is not incidental; it is functional. When refugee movement is controlled and timed, it becomes a pressure vector that Western systems cannot neutralise without harming themselves. Not metaphorically. Not rhetorically. Practically. [1]

Refugees are increasingly easy to weaponise, to great effect and at a low cost. This is not because the refugees themselves are distressed assets, but because the systems that are targeted by those that wield refugees as weapons are constrained. The modern liberal democracy has a firm set of legal obligations, moral self-image, media exposure, and electoral sensitivity to ensure that the cost of displacement is absorbed internally by the receiving state. A good crisis should never be wasted. It is useful. If none exists, one can be produced. [2][3]

This logic depends on unresolved conflict. Frozen conflicts are particularly suited to it, preserving leverage while avoiding the obligation to decide. When a conflict does not conclude, refugee streams do not disappear. They are held in suspension. People remain abroad on temporary permits. Others live near ceasefire lines without security, property rights, or legal clarity. Return is discussed, but deferred. Integration is partial by design. Over time, this produces populations that can be mobilised again quickly and in large numbers, without coordination. The conflict itself does not need to resume. The pressure is already stored. [4][5]

This dynamic is particularly well understood in Moscow. Russian strategy has long favoured frozen conflicts precisely because they preserve leverage without incurring the cost of resolution. Abkhazia, South Ossetia, Transnistria, Donbas, and Nagorno-Karabakh all functioned not merely as territorial disputes, but as reservoirs of instability, including controlled refugee and displacement flows that could be activated, redirected, or merely implied as circumstances required. Refugee streams, in this framework, are not incidental outcomes of conflict but durable instruments embedded in it.

Viktor Orbán required that his ally, the Slovak populist Robert Fico, secure victory. The objective was straightforward and time-bound. Orbán therefore selected one of the most cost-efficient instruments available in his hybrid activities toolbox: the deliberate creation of controlled refugee streams directed toward the Hungarian–Slovak border in the weeks preceding the vote. [6][7]

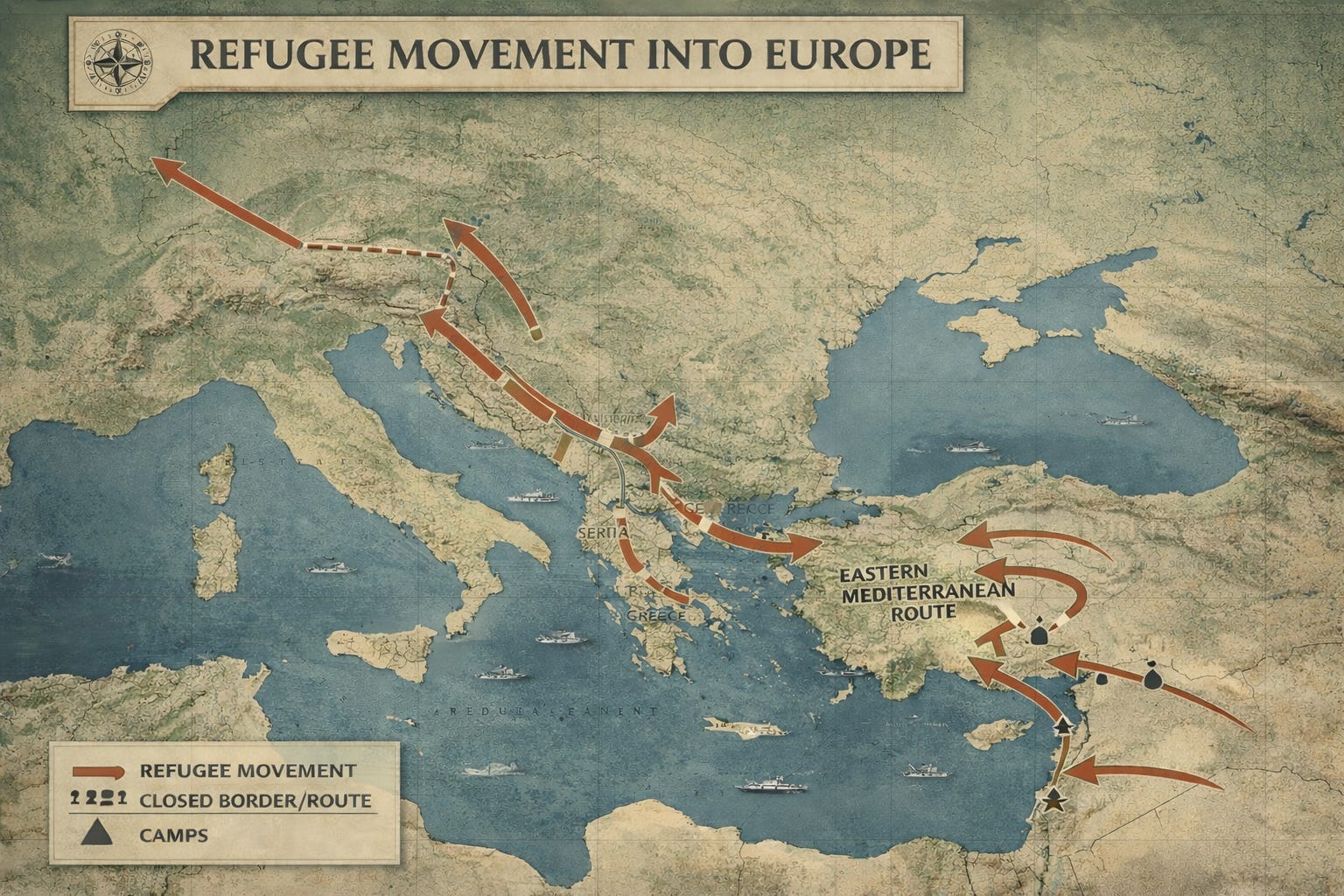

Hungary occupies a critical transit position on the Western Balkan route. Control over that position does not require constant enforcement. It requires discretion over when enforcement is applied and when it is relaxed. In early 2023, the Hungarian government released more than 1,500 convicted people-smugglers from Hungarian prisons, citing cost and overcrowding. Most were foreign nationals. They were instructed to leave Hungary within seventy-two hours. No credible mechanism ensured that they did. Trafficking capacity was returned to circulation at scale. [8][9]

At the same time, Hungarian authorities increasingly opted to issue temporary documentation to migrants rather than detain or return them. Enforcement remained rhetorically strict and operationally uneven. Movement followed deliberately relaxed enforcement, as it reliably does. [10]

Relocation required neither coercion nor formal instruction. It required permissiveness, direction, and the provision of false hope. False hope is useful, and eases logistics.

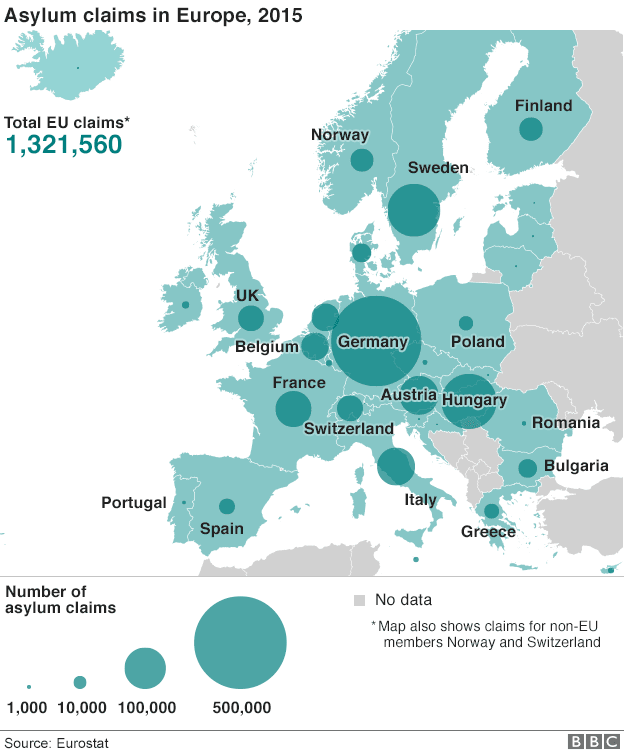

In the months preceding Slovakia’s election on 30 September 2023, migrant presence became increasingly visible in southern Slovak border communities. Groups appeared with regularity. The visibility was new. The timing was precise. Slovak authorities later recorded the scale: more than 27,000 irregular migrants detained in 2023, a ninefold increase from the previous year. The majority were young men travelling north along the Balkan route, transiting Serbia through Hungary and into Slovakia. [11][12]

Migration had already been identified as a decisive political issue. Robert Fico’s SMER-SSD party campaigned explicitly on restoring order and opposing immigration, framing the sitting government as incapable of border control. The sudden, localised visibility of migrants supplied confirmation rather than argument. The crisis did not need exaggeration. It merely needed to exist. [13]

The physical movement was reinforced with an information operation. During late summer 2023, Hungary’s Prime Minister’s Office placed approximately 1.6–1.8 million anti-migration video advertisements into Slovakia via YouTube, a country of 5.5 million inhabitants. The ads depicted migrants breaching fences and Hungarian forces “defending Europe”. Formally categorised as non-political issue messaging, they reached Slovak audiences at scale while refugee streams were being created on the ground. [14][15]

Slovak officials recognised the sequence. Former defence minister Jaroslav Naď publicly stated that Hungary had interfered in Slovakia’s electoral process by deliberately elevating migration as a political issue. Others reached the same conclusion privately. No documentation was required. The sequence was sufficient. [16]

The election produced the intended result. Fico formed a government. Within days, police and military units were deployed to the Hungarian border and routine Schengen procedures were suspended. Within weeks, the situation was declared resolved. Migrant visibility diminished accordingly. Hungary simultaneously tightened its own enforcement once the political objective had been achieved. The controlled refugee streams were throttled. The operation concluded without residue. [17]

Viktor Orbán did not invent this method, but he applied it with discipline.

The receiving state absorbed the cost: public anxiety, municipal strain, media saturation, and electoral pressure. Hungary absorbed none of it, while continuing to present itself as Europe’s defender. The intervention required no secrecy, no escalation, and no formal coordination. It relied on timing, permissiveness, and a neighbouring system structurally incapable of externalising humanitarian pressure. [18]

Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan operates the same instrument at continental scale, with an added refinement: availability on demand. [19]

Turkey hosts several million refugees, primarily from Syria. This alone does not constitute leverage. The leverage lies in Ankara’s ability to weaponise refugee streams on demand by controlling onward movement and signalling when that control may be withdrawn. Erdoğan does not need to relocate refugees. He needs only to regulate permeability, and to make credible that such regulation can cease at will. [20][21]

This has been demonstrated repeatedly. At moments of political friction with the European Union, Ankara has allowed refugee movement toward Greece to accelerate, slowed it when concessions were secured, and threatened its release when negotiations stalled. Sometimes movement followed. Sometimes it did not. The outcome was largely the same. European governments adjusted funding, softened criticism, and recalibrated policy to reduce domestic exposure. [22][23]

The pressure was never framed as coercion. No ultimatums were issued. No formal demands were tabled. Instead, it was presented in humanitarian terms: capacity limits, fatigue, financial burden. Turkey did not describe refugee streams as a political choice. It described them as inevitability. The streams themselves performed the argument, while European political systems processed the consequences internally. [24]

From Ankara’s perspective, this is a near-ideal instrument. It is controllable, reversible, and deployable on demand. No treaty is formally violated. No military threshold is crossed. Yet policy shifts repeatedly in Turkey’s favour. The key point is not the absence of coercion, but the absence of any need for it. Weaponised refugee streams function as a standing system: one that does not require activation to retain effect. The credible availability of movement is sufficient to shape policy inside European states without Turkey having to cross any formal threshold at all. [25]

Refugee streams cross borders carrying obligations that liberal democracies cannot refuse without violating their own identity. Courts intervene. Media amplifies. Municipal budgets strain. Coalition politics fracture. Elections polarise. The enabling actor remains external to consequence, while the receiving state disciplines itself.[26]

Once refugee movement is weaponised, it ceases to be a humanitarian by-product and becomes a managed resource. Controlled refugee streams can be stored, released, paused, resumed, or merely signalled. They do not need to be activated to retain effect. They need only to remain unresolved and available. [27]

In this context, crises are not anomalies to be avoided, but conditions to be governed. Some are prolonged because they continue to generate leverage. Others are stabilised just enough to prevent resolution. A crisis that already exists and produces pressure is a good crisis, and good crises should never be wasted. [28]

When no such crisis is available, one can be produced without fabrication. Conditions are adjusted rather than events invented. Enforcement is relaxed selectively. Movement is redirected. Visibility is increased at moments of political sensitivity. The crisis does not need to be large or continuous. It needs only to be legible to systems that cannot refuse to respond. [29]

This is why the weaponisation of refugee streams is so effective. It produces consequence without escalation and pressure without violation. It allows one actor to remain formally compliant while another absorbs cost internally through law, media, administration, and electoral politics. Nothing illegal is required. Nothing dramatic needs to occur. The burden is carried entirely by the receiving system. [30]

Nothing about this is new. Those who see refugees as useful instruments will weaponise them, and if no crisis exists to enable it, one will be created.

Happy New Years.

John Sjoholm, for LIMA CHARLIE WORLD

[Subscribe to our newsletter for free and be the first to get Lima Charlie World updates delivered right to your inbox.]

John Sjoholm is Lima Charlie’s Middle East Bureau Chief, Managing Editor, and founder of the consulting firm Erudite Group. A seasoned expert on the Middle East, North Africa, Europe and the Balkans, he has a background in security contracting and has served as a geopolitical advisor to regional leaders. He was educated in religion and languages in Sana’a, Yemen, and Cairo, Egypt, and has lived in the region since 2005, contributing to numerous Western-supported stabilisation projects. He currently resides in Jordan.

Offline References:

[1] Kaldor, Mary. New and Old Wars: Organized Violence in a Global Era. Stanford University Press. ISBN 9780804739633.

[2] Betts, Alexander. Survival Migration. Cornell University Press. ISBN 9780801448729.

[3] Greenhill, Kelly M. Weapons of Mass Migration. Cornell University Press, 2010. ISBN 9780801477583.

[4] OSCE. Protracted Conflicts in the OSCE Area. EASI Report, 2012.

[5] Trenin, Dmitri. Post-Imperium: A Eurasia Story. Carnegie Endowment, 2011. ISBN 9780870032911.

[6] Politico Europe. “Slovakia election puts migration front and center.” Sept 2023.

[7] Reuters. “Hungary’s Orban backs Slovakia’s Fico ahead of vote.” Sept 2023.

[8] Hungarian Government Decree No. 148/2023.

[9] EU Commission Statement on Hungary releasing people smugglers, April 2023.

[10] Austrian Interior Ministry complaint to EU Council, May 2023.

[11] Slovak Police Presidium Annual Report 2023.

[12] Frontex. Western Balkans Route Analysis 2023.

[13] SMER-SSD Campaign Manifesto, 2023.

[14] Direkt36.hu investigation on Hungarian government YouTube ads.

[15] Transparency International Slovakia, Media Monitoring Report 2023.

[16] Jaroslav Naď public statements, September 2023 (Denník N).

[17] Slovak Interior Ministry press releases, October 2023.

[18] OSCE ODIHR Election Observation Commentary, Slovakia 2023.

[19] Erdoğan, Recep Tayyip. Public speeches on migration, 2016–2023.

[20] UNHCR. Türkiye Refugee Statistics.

[21] European Council. EU–Turkey Statement, 18 March 2016.

[22] BBC. “Turkey threatens to open borders for refugees.”

[23] European Court of Auditors. EU Support to Refugees in Turkey.

[24] European Parliament Research Service, Migration and Externalisation, 2021.

[25] Greenhill, Kelly M. Weapons of Mass Migration, Chapters 1–3.

[26] European Commission Asylum Procedures Directive (2013/32/EU).

[27] OSCE Secretariat. Mediation in the OSCE Area.

[28] Kissinger, Henry. World Order. Penguin. ISBN 9781594206146.

[29] Trenin, Dmitri & Lo, Bobo. The Landscape of Russian Foreign Policy Decision-Making. Carnegie Endowment, 2005.

[30] Martyanov, Andrei. The (Real) Revolution in Military Affairs. Clarity Press. ISBN 9781949762077.

Lima Charlie World provides global news, featuring insight & analysis by military veterans, intelligence professionals and foreign policy experts Worldwide.

For up-to-date news, please follow us on twitter at @LimaCharlieNews

In case you missed it: