Economic sanctions have long been the preferred foreign policy tool to outright aggression. Whether to restrict or enhance military capabilities, force or weaken political ideologies, or respond to human rights violations, countless analysts and statesmen have debated their effectiveness. Yet rising tensions with a developing China have forced many in the West to rethink the strategy, with advances in technology becoming a critical focal point of the debate.

The announcement in September by the Biden Administration of a deal between the U.S., the UK and Australia (AUKUS), to deploy and share nuclear submarine technology in hopes of pushing back against Chinese influence in the Indo-Pacific region, highlights the momentous shift in U.S. attitude towards China in recent years. Lima Charlie News has reported extensively about China’s economic and military moves in the South China Sea, as well as throughout Africa, the EU and the world, expanding soft power and “sharp power” influence, its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), and clashes with the West on various issues that include the autonomy of Hong Kong, Taiwan, ASEAN and the South China Sea, technology, and human rights.

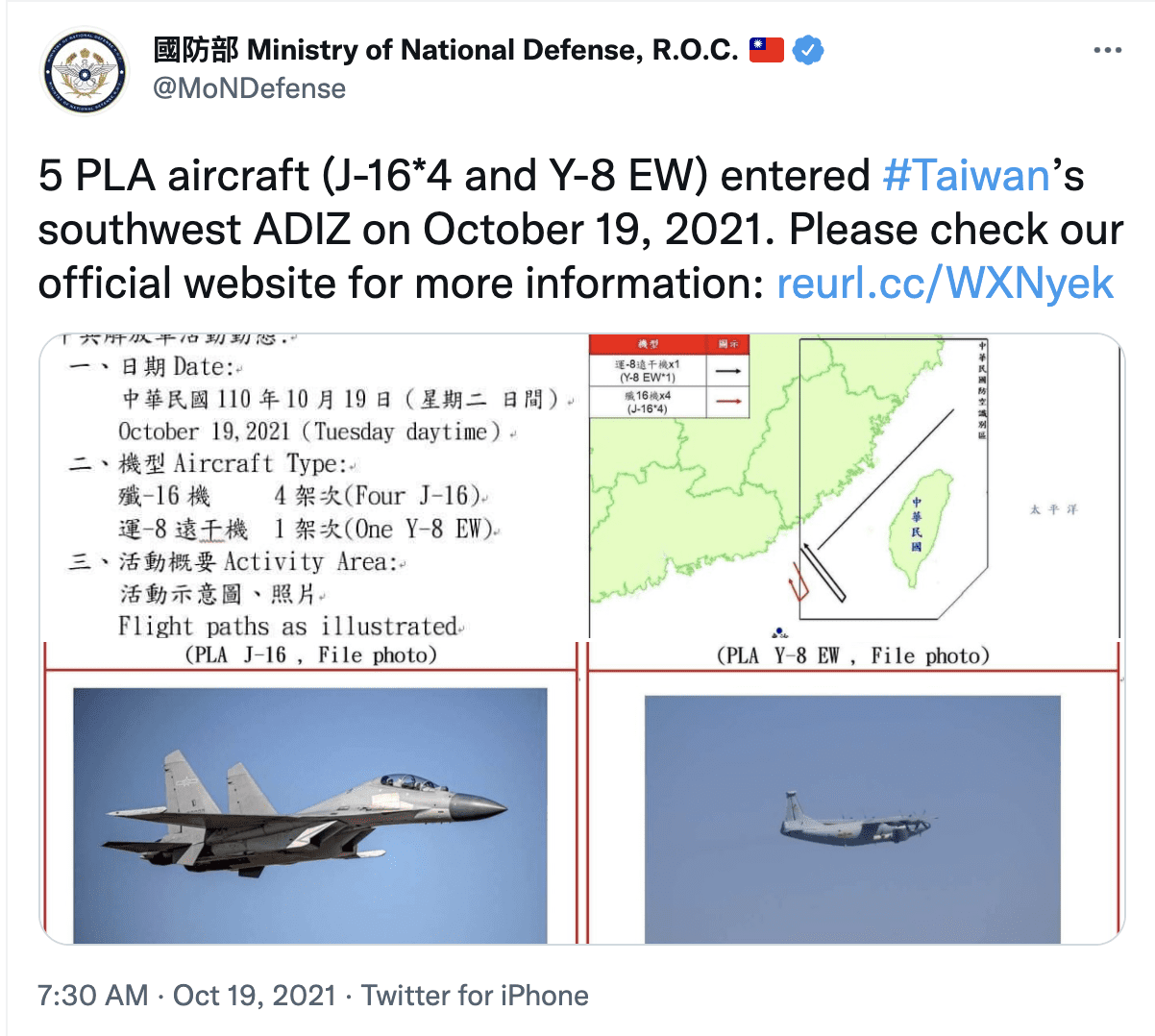

This year saw the largest incursion yet of the People’s Liberation Army Air Force (PLAAF) into Taiwan, with dozens of military aircraft, including nuclear-capable bombers and anti-submarine aircraft, entering Taiwan’s air defense identification zone, causing another potential flashpoint in U.S.-China relations. Such incursions are ongoing.

Adding to tensions have been disputes over the origins of COVID-19, a pandemic fueling a devastating economic and health crisis that has affected the economies, health and well-being of billions worldwide.

This year, amid allegations of China being behind a massive hacking of Microsoft, intelligence warnings of a low-level cyber war with China have intensified. This prompted China’s foreign ministry to accuse the U.S. in July of “ganging up with its allies” and engaging in “smear and suppression out of political motives,” asserting that the U.S. was “the largest source of cyber-attacks in the world.”

While tensions between the U.S. and China have manifested in, what is arguably a trade war that has been ongoing since 2018, Americans across party lines are supporting a range of tougher policies against China.

Given the evolving dynamics between the countries, it is more relevant than ever to examine the tools of foreign policy the U.S. has and can use to manage its relationship with China. Always controversial, economic sanctions have been a preferred tool.

The evolving use of sanctions as a tool of foreign policy

Historically, the use of international sanctions generally falls into categories that include economic sanctions, diplomatic sanctions, military sanctions, sanctions connected to cultural or athletic (sports) restrictions, and more recently, environmental sanctions that concern international environmental protection efforts. They are the primary foreign policy tools that sovereign powers or global and regional organizations can use to influence nations, entities, or even individuals that violate international norms of behavior. Favored by policymakers who see them as a more efficient method of achieving foreign policy objectives, being more punitive than diplomacy but lower cost than military action, economic sanctions are becoming an increasingly important tool of American foreign policy. Just this year, the U.S. imposed sanctions on individuals who have undermined Hong Kong’s autonomy, targeted Myanmar’s junta, and marked Russian entities and officials linked to cyberattacks. In 2020, there were 777 sanctions designations, with ninety designations of Chinese entities and individuals.

In addition to the increasing use of sanctions to achieve foreign policy objectives in recent decades, the nature of the sanctions imposed has also been shifting. There is a broader variety of sanctions, and the sanctions are more directed at specific targets.

This tool of foreign policy has been used throughout history in various forms. In 432 B.C. in Ancient Greece, economic sanctions were used by the city of Athens to ban Megara traders from its marketplaces to target their economy and compel a change in behavior. This arguably helped trigger the Peloponnesian War. In medieval Europe, during the Crusades and Commercial Revolution, embargoes enacted by the Papal States were intended to prevent or restrict trade with Islamic states, while the economic and maritime powerhouse, Republic of Venice, enacted embargoes during its ongoing conflict with the Ottoman Empire.

Centuries later, the American colonies would come to boycott British goods over oppressive taxation, a prelude to the Revolutionary War. Caught between the British and French during the Napoleonic Wars, the U.S. would enact the Embargo Act of 1807, among other restrictions on trade with Great Britain, that would eventually lead to the War of 1812. Throughout the 1800s, France, Britain, Germany, Spain and Russia employed various economic sanctions, embargoes and blockades prefacing and resulting in the Napoleonic Wars, the Franco-Prussian War and the Crimean War.

20th Century, Communism and the Cold War

The modern sanctions regime, however, emerged in the 20th century when the League of Nations enforced multilateral sanctions in order to uphold the Covenant of the League of Nations and encourage collective security. Its modern counterpart, the United Nations, has played a similar role with the UN Security Council passing sanctions resolutions that include asset freezes, travel bans, and arms embargoes.

In 1948, as the Cold War heated up, the U.S. and Western allies embarked on a decades long strategy to isolate and defeat communism through economic sanctions beginning with the Soviet Union and China, though China would be treated more harshly, as explained further below. The Export Control Act of 1949 (ECA), intended to restrict the export of strategic materials and equipment to Soviet bloc nations (reasons being national security, foreign policy, and short supply), would come to include China, North Korea and various communist countries. The ECA would be extended in 1951, 1953, 1956 and again in 1958. The ECA was supported by subsequent trade and sanction legislation including the Mutual Defense Assistance Control Act of 1951 (Battle Act)(an “embargo on the shipment of arms, ammunition, and implements of war, atomic energy materials, petroleum, transportation materials of strategic value”), and the Export Administration Act (EAA) of 1969, reestablished in 1979, and amended.

In February 1962, President John F. Kennedy would announce an embargo on trade between the U.S. and the communist regime in Cuba, resulting in decades of crushing economic sanctions, many of which remain in place today.

In the 1970s, certain exceptions to trade restrictions were made, for example as with wheat when Soviet crops failed in 1973. Restrictions would tighten during periods of aggression, such as when the Soviets invaded Afghanistan in December 1979.

In January 1983, Ronald Reagan approved the National Security Decision Directive 75 (NSD 75), which set out three elements of U.S. policy towards the Soviet Union: external resistance to Soviet imperialism; internal pressure on the USSR to weaken the sources of Soviet imperialism; and negotiations to eliminate, on the basis of strict reciprocity, outstanding disagreements.

To that end, NSD 75 set U.S. economic policy objectives that were geared primarily to both inhibit Soviet military strength and to weaken communist sentiment worldwide. This included initiatives to prevent the transfer of technology and equipment that could aid Soviet military power, to avoid “subsidizing the Soviet economy or unduly easing the burden of Soviet resource allocation decisions” in order to maintain pressure for change in the Soviet communist system, to decrease any leverage the Soviet Union may have on Western countries based on trade, energy supply, and financial relationships, and to permit mutual beneficial trade with the USSR in non-strategic areas, such as grain imports.

While nuclear non-proliferation (central to technology based sanctions), and the demise of communism were critical goals during the Cold War, U.S. economic pressure on the Soviets would lead to considerable conflict with its allies over energy needs and the export of oil and gas equipment.

“Sanctions were used against the USSR starting almost immediately after World War II, but they were always of limited effectiveness. It is one thing to sanction a potentially hostile nation, but it is far more difficult to persuade all of your allies to do the same,” said Douglas A. Drabik, professor of history and author specializing in the Soviet Cold War era. Drabik added, “with the exception of high end military technology, the Soviets were almost always able to find a supplier for what they required.”

Post Cold War sanctions

After the Cold War, the use of economic sanctions intensified dramatically, and by the 1990s there were nearly as many sanctions imposed as during the first ninety years of the 20th century. Notable usage during this period includes United Nations sanctions against Iraq, Haiti, and the former Yugoslavia. Despite modest policy concessions that resulted from the use of sanctions during this period, many policy analysts and researchers who have studied these measures deemed them a failure due to the costs they imposed on civilians in those countries.

In Iran, for example, the price of a family’s food increased over 250-fold over the first five years of the sanctions regime and led to the excess deaths of an estimated 100,000 to 250,000 young children between 1991 and 1992. This led to an increased reluctance in policy makers to use broad-based economic sanctions that would damage the entire economy of a country. The full impact to the civilian population of Iraq, of over a decade of sanctions from 1990 to the 2003 invasion, however, has led to heated debate. For example, allegations arose that common cited data as to child mortality rates resulting from the economic sanctions had been doctored by the Saddam Hussein regime.

A significant shift in the use of sanctions came after 9/11, where the attacks by al Qaeda on the U.S. mainland led President George W. Bush to issue Executive Order (EO) 13224. This directive gave Treasury Department officials far-reaching authority to freeze financial transactions and assets of individuals and entities suspected of supporting terrorism. Bush also threatened to bar any foreign bank that did not comply with the order from doing business in America. Given the dominance of the U.S. dollar in trade and finance, this increased risks for financial institutions that engaged with these entities and fundamentally shifted the financial regulatory environment.

These developments brought about an increased use of “smart” or targeted sanctions, where the sanctions imposed are directed at specific individuals or entities, such as elite members of a targeted regime, rather than the entire nation. By restricting access of actors to U.S. owned or influenced financial systems, the goal is to incentivize a change of behavior in these specific actors while minimizing the impact of financial hardship on the larger public.

In addition to the focus on specific targets, the variety of sanctions used has also grown. While trade embargoes were frequently used in the past, sanctions now include a wider range of actions which are tailored to the circumstances of the industries, organizations, and individuals who are targeted.

For example, in 2019, allegations of security risks led the U.S. to impose sanctions against Chinese multinational tech company Huawei Technologies Co., Ltd., which restricted any foreign semiconductor company from selling chips developed or produced using U.S. technology to Huawei, including barring Google from providing technical support to new Huawei phone models and access to Google Mobile Services. Sanctions against Huawei, among other Chinese companies, have continued into the Biden Administration.

How are U.S. sanctions implemented?

Given the wide-ranging impact of U.S. sanctions, it is worth examining their legal basis, the implementation process, and enforcement mechanism.

A U.S. president derives the power to enforce sanctions today primarily through the National Emergencies Act (NEA), which establishes the framework for the declaration of emergencies, and the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA), which confers “broad authority to regulate financial and other commercial transactions involving designated entities” after declaring a national emergency in response to any “unusual and extraordinary threat” to the U.S. that originates “in whole or substantial part outside the United States”. The NEA was signed by President Gerald Ford in 1976 (50 U.S.C. § 1601 et seq.), and the IEEPA was signed by President Jimmy Carter in 1977 (50 U.S.C. § 1701 et seq.). The IEEPA authorizes the president to block transactions and freeze assets to deal with such threat. Together, these acts allow the president to provide a relatively quick response to international issues of concern.

After a foreign policy threat has been identified, experts from relevant executive branch agencies are convened by the National Security Council. These experts often include representatives from Defense, State, and Treasury Departments, members of the intelligence community, and members of law enforcement. Interagency deliberations will often take place, with a key focus on how allies will react to the foreign policy problem. If allies support the sanctions effort and impose multilateral sanctions, these will often be more effective than unilateral sanctions imposed solely by America. A recent example of multilateral sanctions is the joint efforts by the European Union (EU), the U.S., Canada, and the UK to signal dissatisfaction at China over the treatment of Uyghurs in Xinjiang.

While senior policymakers set expectations on the desired impact of the sanctions on a macro level, the target selection is primarily driven by the intelligence community and law enforcement, who utilize their expertise and knowledge to make sure the impact is calibrated. After the targets and sanctions measures are determined, attorneys from the Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) draft an executive order, a signed, written, and published document from the president used as a means of issuing federal directives. The draft executive order is coordinated with the legal team at the Department of State and the Department of Justice to ensure that it meets legal requirements. The draft recommendation is then presented up the chain of command and finally put forth to the president for a decision.

After the president approves the sanctions and declares a national emergency, the sanctions are rolled out for state agencies and the private sector. OFAC will place sanctioned individuals or entities on the Specially Designated Nationals and Blocked Persons List and will often issue frequently asked questions that give additional guidance to the private sector who are responsible for adhering to the scope of the sanctions. For entities or individuals that do not abide by sanctions laws, currently, civil and criminal penalties of up to twenty years imprisonment and $1,000,000 in fines per violation can result. Civil penalties vary based upon the specific sanctions program and the monetary amount, which is adjusted annually by OFAC.

In addition to the monetary and legal risks, there are also reputational and operational risks for entities that fail to follow relevant laws. For example, French international banking group BNP Paribas S.A., currently the largest bank in Europe and the seventh largest bank in the world by total assets, pleaded guilty in 2014 to processing billions of dollars in financial transactions for blacklisted Cuban, Iranian, and Sudanese entities, which led to a historic fine of $8.9 billion as well as suspension of its dollar clearing capabilities, the ability to convert payments on behalf of clients into U.S. dollars from a foreign currency, for one year.

The Magnitsky Act and the Russian Sanctions Regime

After almost 9 years since the enactment of the Magnitsky Act, and 6 years since the death of Sergei Magnitsky, the consensus is that economic sanctions have had a significant impact, even affecting Russia’s GDP, which has not grown since 2014.

One significant piece of sanctions regulations put in place in recent years is the Global Magnitsky Human Rights Accountability Act (Global Magnitsky Act), which sanctions foreign government officials implicated in human rights abuses anywhere in the world. The Sergei Magnitsky Rule of Law Accountability Act of 2012 (the Magnitsky Act), originally signed into law by President Barack Obama, arose from Russia’s treatment of Sergei Leonidovich Magnitsky, a Russian tax advisor to Hermitage Capital Management. Hermitage is an investment fund and asset management company specializing in Russian markets, co-founded by financier political activist Bill Browder.

By 2005, Hermitage’s value had reportedly reached $4.5 billion, and while Browder had publicly praised Vladimir Putin, for years his company had reputedly targeted corporate corruption in Russia, including becoming what he described as a “shareholder activist” in Russian energy giants like Gazprom and Surgutneftegaz. Likewise, Browder, Hermitage and even Magnitsky had been accused by Russian tax authorities of evading taxes and siphoning funds to offshore accounts, as early as 2004, sparking investigations.

By November 2005, Browder’s visa was revoked, he was blacklisted by the Russian government, banned from entering Russia, and was deemed a “threat to national security.” Hermitage allegedly refused to submit to bribes to resolve the problem. By May 2006, the Tax Crimes Department of the Ministry of the Interior had requested company and bank documents from Hermitage.

On 4 June 2007, Russian Ministry of Internal Affairs (MVD) police raided Hermitage’s Moscow offices and its law firm Firestone Duncan over allegations of tax fraud. Corporate documents, tax documents and computers were confiscated. Browder assigned Magnitsky, an auditor at Firestone Duncan, to investigate. Magnitsky and his colleagues reportedly uncovered a $230 million (5.4 billion ruble) tax fraud involving Russian tax officials and three Hermitage-owned companies.

The Magnitsky investigation would eventually conclude that the 2007 MVD raid was a “corporate raid” resulting in the theft and loss of control of the three Hermitage-owned companies to organized criminals (the “Klyuev gang”), possibly with the help of Russian police, tax officials, bankers, the judiciary, and government officials. According to Magnitsky, these corrupt individuals conspired to fraudulently reclaim hundreds of millions in taxes previously paid by Hermitage to the Russian Federation, with one such tax refund amounting to the largest in Russian history. Hermitage advised Russian authorities of the conclusions of Magnitsky’s investigation, and Magnitsky testified before the State Investigative Committee in June and October 2008.

In November 2008, Magnitsky was placed under arrest, accused of colluding with Hermitage to evade taxes, and detained at the Butyrka prison in Moscow. Magnitsky was held for eleven months without trial. During this period, he developed gall stones, pancreatitis, and calculous cholecystitis, and was given grossly inadequate medical care. Surgery was ordered, but never performed, and Magnitsky eventually died on 16 November 2009 while in his cell at the pretrial detention facility known as “Matrosskaya Tishina.” Evidence showed that Magnitsky had also been severely beaten while imprisoned.

In 2012, Congress passed the Magnitsky Act, which requires the president to impose sanctions on individuals involved in the “criminal conspiracy” uncovered by Magnitsky. This was followed by the passage of the Global Magnitsky Act in 2016, which applies the 2012 laws globally. The 2016 Act also expanded the designation to include individuals “responsible for extrajudicial killings, torture, or other gross violations of internationally recognized human rights,” as well as foreign government actors responsible for significant corruption.

Both President Trump and President Obama signed a series of executive orders during their administrations, imposing a range of sanctions against Russia over issues including malicious cyber activities, the use of chemical weapons, weapons proliferation, as well as North Korea, Syria, and Venezuela-related sanctions violations.

In addition to the sanctions under the Global Magnitsky Act, a large number of sanctions were imposed on Russian individuals and entities in response to Russia’s 2014 invasion and annexation of Crimea and its subsequent role in instigating conflict in Ukraine. President Obama issued a series of four executive orders which sanctioned more than 680 individuals, entities, vessels, and aircrafts by placing them on OFAC’s Specially Designated Nationals List. This was part of a broader set of multilateral sanctions, where the EU, Norway, Canada, and Australia, also adopted sanctions actions against Russia. Functioning as a tool of nonrecognition policy, these sanctions highlighted that these countries do not recognize the Russian annexation of Crimea. Russia responded with its own sanctions, including a food import ban against these countries.

In June 2017, despite opposition by then President Donald Trump, the U.S. Congress, with overwhelming majority support, adopted the Combating American Adversaries Through Sanctions Act (CAATSA), legislation that incorporated the provisions of the Countering Russian Influence in Europe and Eurasia Act of 2017 (S. 1221).

CAATSA, influenced by Russia’s ongoing involvement in the wars in Ukraine and Syria and its interference in the U.S. 2016 election, was designed to expand punitive measures imposed by executive orders and convert them into law.

As stipulated by Section 241 of the bill (“Report On Oligarchs And Parastatal Entities Of The Russian Federation”), the Treasury Department was mandated to release a list identifying “the most significant senior foreign political figures and oligarchs in the Russian Federation, as determined by their closeness to the Russian regime and their net worth.”

On December 20, 2017, President Trump issued Executive Order 13818 invoking the Global Magnitsky Act. As of October 2020, OFAC had publicly designated 107 individuals under this executive order. On April 15, 2021, President Biden signed Executive Order 14024, expanding sanctions against Russia and imposing sectoral sanctions on Russia’s central bank, finance ministry, and sovereign wealth fund, signaling continued commitment to the use of sanctions as a foreign policy tool against Russia.

After almost 9 years since the enactment of the Magnitsky Act, and 6 years since the death of Sergei Magnitsky, the effectiveness of the Magnitsky Acts, CAATSA, and various sanctions having been imposed upon Russian individuals and entities, the consensus is that economic sanctions have had a significant impact, even affecting Russia’s GDP, which has not grown since 2014. Counter efforts to downplay or negate the allegations raised by Browder and Magnitsky are ongoing, even entering the realm of controversial documentaries.

While the overall effectiveness of sanctions against Russia is not the subject of this article, Lima Charlie News has examined the subject in various articles, including Dr. Gary K. Busch’s “Sanctions and the Rise of Putin’s Russia (starring oligarchs, siloviki, Rossiyskaya mafiya and Oleg Deripaska),” and John Sjoholm’s “Aluminium prices stabilize after U.S. eases Russia sanctions for aluminium giant Rusal.”

This Tuesday, October 19, 2021, F.B.I. agents raided homes linked to Russian billionaire Oleg Deripaska, as part of an investigation into whether he violated U.S. sanctions. Under the Trump administration, sanctions were imposed on Deripaska in 2018 by the U.S. Treasury Department, however sanctions against his companies were lifted in 2019. In a lawsuit filed by Deripaska in March 2019, his lawyers claimed that the sanctions had cost him billions, made him “radioactive” in international business circles, and exposed him to criminal investigation and asset confiscation in Russia.

U.S. Sanctions on China

What distinguishes Sun Tzu from Western writers on strategy is the emphasis on the psychological and political elements over the purely military.”

– Henry Kissinger, On China

Similar to sanctions against Russia, sanctions against the People’s Republic of China have also been used as a foreign policy tool on issues where the U.S., the West and China have differing interests. Unlike the sanctions imposed against Russia, however, most economic sanctions against China are relatively recent, reflecting the current rise in geopolitical tensions between the two countries.

Beginning in 1949, after Mao Zedong led the Chinese Communist Party to victory, and during the Korean War, the U.S. sought primarily to restrict, via embargo, all technology or machinery that could be used in the production of military weapons, including nuclear weapons and technology. As detailed in the Journal of Transatlantic Studies (Cain, 2020) America’s trade embargo against China and the East in the Cold War Years), the Truman administration first enumerated items to be banned, and President Eisenhower enabled US embassy officials to police the bans. The U.S. simultaneously engaged in support of the economic development of non-communist countries and allies in the region, such as Japan, Philippines and Taiwan.

While Western alliances had agreed with the U.S. to limit trade with the USSR and Eastern Bloc, due to U.S. pressure, China remained under tighter restrictions via a policy known as the China differential. President Eisenhower, however, favored trade and engagement with China, which he believed could help wean the PRC off of its relationship with the Soviet Union and possibly communist principles, and avoid a costly economic embargo from harming America’s allies in the region. Eisenhower faced opposition from members of his own cabinet, the CIA and Defense, who favored isolating China. Western and Asian allies, especially Japan seeking to rebuild after World War 2, sought to open lucrative trade with Hong Kong and China. These fractures would eventually widen.

During the Kennedy administration, trade embargo restrictions against China were loosened somewhat, then reimposed by President Johnson. President Nixon (with the advice of Secretary of State and National Security Advisor, Henry Kissinger) would eventually strive to build greater relations with China. Dr. Kissinger would remain a vocal proponent of seeking “an agreement in principal between the two giants” that “is essential.”

By 1989, America would come to impose a series of economic sanctions on China after the Tiananmen Square protests and violent government crackdown. However, all but two of the sanctions have been made obsolete by circumstances, broadly waived or removed on a case-by-case basis.

The recent increased use of targeted sanctions began primarily during the Trump presidency and focused on the use of technology. In August 2018, expanding upon the National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) first passed in 1961, President Trump signed the John S. McCain National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2019 (NDAA 2019), which included a ban on U.S. federal government use of Huawei and ZTE equipment, citing national security concerns.

Critics argued the legislation contained “watered-down” measures, and failed to reinstate tougher sanctions on ZTE to punish the company for illegally shipping products to Iran and North Korea. At that time, the Department of Commerce also listed both companies on its Entity List under the Export Administration Regulations.

These steps are part of the larger technology decoupling between America and China, which has been expanding in both scale and scope. With the COVID-19 pandemic exposing supply chain vulnerabilities, in June 2021, the U.S. Senate also passed new policy legislation aimed at boosting American technology capabilities. The U.S. Innovation and Competition Act of 2021 (USICA), is a bipartisan $250 billion bill aimed at countering China’s technological gains while giving the U.S. a competitive edge. USICA commits funding towards scientific research, subsidies for semiconductor research, design, and manufacturing initiatives, robot / artificial intelligence development, and an overhaul of the National Science Foundation (NSF), establishing a Directorate for Technology and Innovation.

According to AP, China responded to the legislation by objecting to being cast as an “imaginary” U.S. enemy.

In addition, in June 2021, the U.S. and European Union issued a joint summit statement emphasizing their intention to coordinate more closely on various shared goals, including technology issues. Titled, “Towards a Renewed Transatlantic Partnership,” the statement references the long shared democratic values between the U.S. and EU, and lays out four primary goals: “(i) end the COVID-19 pandemic, prepare for future global health challenges, and drive forward a sustainable global recovery; (ii) protect our planet and foster green growth; (iii) strengthen trade, investment, and technological cooperation; and (iv) build a more democratic, peaceful, and secure world.” By establishing the U.S.-EU Trade and Technology Council (TTC), the pact seeks to “cooperate on the development and deployment of new technologies based on our shared democratic values, including respect for human rights, and that encourages compatible standards and regulations.”

With an eye towards nations such as China and Russia, the partnership states:

“We reject authoritarianism in all its forms around the globe, resisting autocrats’ efforts to create an environment that protects their rule and serves their interests, while undermining liberal democracies. We intend to enhance cooperation on the use of sanctions to pursue shared foreign policy and security objectives, while avoiding possible unintended consequences for European and U.S. interests.”

The partnership agreement devotes an entire section to Russia and China, declaring with regard to China:

“We intend to closely consult and cooperate on the full range of issues in the framework of our respective similar multi-faceted approaches to China, which include elements of cooperation, competition, and systemic rivalry. We intend to continue coordinating on our shared concerns, including ongoing human rights violations in Xinjiang and Tibet; the erosion of autonomy and democratic processes in Hong Kong; economic coercion; disinformation campaigns; and regional security issues. We remain seriously concerned about the situation in the East and South China Seas and strongly oppose any unilateral attempts to change the status quo and increase tensions. We reaffirm the critical importance of respecting international law, in particular the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) noting its provisions setting forth the lawful maritime entitlements of States, on maritime delimitation, on the sovereign rights and jurisdictions of States, on the obligation to settle disputes by peaceful means, and on the freedom of navigation and overflight and other internationally lawful uses of the sea. We underscore the importance of peace and stability across the Taiwan Strait, and encourage the peaceful resolution of cross-Strait issues. We intend also to coordinate on our constructive engagement with China on issues such as climate change and non-proliferation, and on certain regional issues.”

Increased efforts by the U.S., EU and China, to limit technology integration and to foster technological development, have resulted in a reduced dependence and greater strategic decoupling between the technology sectors in these countries.

China has also signaled its intention to become more independent, making technological self-reliance a key theme in its 14th Five-Year Plan (2021-2025).

Covington’s Global Policy Watch (“Spotlight on Semiconductors,” April 2021), states that technology is a “core focus of the plan” with several chapters dedicated to “describing how China’s leaders hope to transform the country into an innovation powerhouse.” According to GPW, the semiconductor industry “is a core component of this effort as China sees semiconductor capabilities and supply as intrinsically linked to its economic and national security, a conviction that has sharpened in recent years as U.S. policy has taken aim at Chinese supply chain vulnerabilities.”

These efforts by the U.S., EU and China, to limit technology integration (NDAA 2019), to cooperate to limit and expand technology development (U.S.-EU Summit Statement), and to foster technological development (USICA and China’s 14th Five-Year Plan), have resulted in a reduced dependence and greater strategic decoupling between the technology sectors in these countries.

In addition to technology, other areas of conflict have also been the subject of sanctions between America and China. Different from the technology decoupling, however, are broader multilateral sanctions by coordinated Western nations against various infringements of autonomy and human rights in China.

On July 9, 2020, the Trump administration imposed sanctions and visa restrictions against senior Chinese officials under the Uyghur Human Rights Policy Act. These sanctions have been further reaffirmed recently as part of broader efforts by the U.S., Canada, the EU, and UK to protest “human rights violations and abuses” in Xinjiang.

In addition to human rights abuses, in July 2020, President Trump signed into law the Hong Kong Autonomy Act (HKAA), which imposes sanctions on officials and entities in Hong Kong and mainland China that are deemed to help violate Hong Kong’s autonomy. Pursuant to the HKAA, in August 2020, the U.S. imposed sanctions against eleven individuals, including Hong Kong Chief Executive Carrie Lam, for “undermining Hong Kong’s autonomy and restricting the freedom of expression or assembly.” On December 7, 2020, fourteen Vice Chairpersons of the National People’s Congress of China were further sanctioned in relation to this issue.

On March 18, 2021, the eve of U.S.-China meetings in Alaska, the Biden Administration announced a series of sanctions against twenty-four officials linked to China’s crackdown on democracy in Hong Kong.

On July 16, 2021, pursuant to an advisory (Hong Kong Business Advisory – Risks and Considerations for Businesses Operating in Hong Kong), the Biden Administration imposed additional sanctions on seven deputy directors of the central government’s Liaison Office in Hong Kong. The advisory was ostensibly “to highlight growing risks” associated with actions undertaken by the PRC and the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (SAR) “that could adversely impact U.S. companies” that operate in the Hong Kong SAR of the PRC. The growing risks referred to are due to changes to Hong Kong’s laws and regulations, namely, the Law of the People’s Republic of China on Safeguarding National Security in the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (National Security Law, or NSL) signed on June 30, 2020. The risks fall into four categories: risks for businesses following the imposition of the new law; data privacy; risks regarding transparency and access to critical business information; and risks for businesses with exposure to sanctioned Hong Kong or PRC entities or individuals.

The July 2021 Advisory warns that the new NSL introduced a heightened risk of PRC and Hong Kong authorities using expanded legal authorities to collect data from businesses and individuals for actions that may violate “national security”, including via electronic surveillance without warrants and the required surrender of data to these authorities.

Mirroring U.S. policy towards China regarding human rights issues, in July 2021, Members of the Parliament of the European Union (MEPs) voted to adopt three resolutions on the human rights situation in Hong Kong, Saudi Arabia and Iran. The resolutions called for further actions, encouraging “EU countries to impose sanctions against individuals and entities responsible for serious violations of human rights and international law in Hong Kong under the EU human rights sanctions regime.” Per the MEPs statement, “The resolution also calls on the Hong Kong authorities to stop harassing and intimidating journalists, release arbitrarily detained prisoners, and denounces any attempts to muzzle pro-democracy activists and their activities,” while it encourages EU countries to decline invitations to attend the Beijing 2022 Winter Olympics, “unless the Chinese Government demonstrates a verifiable improvement in the human rights situation in Hong Kong, the Xinjiang Uyghur Region, Tibet, Inner Mongolia and elsewhere in China.”

The Impact of Sanctions

The irony of sanctions is that while they may induce certain behavior in the short-term, this will also corrode their effectiveness in the long-term.

While governments are willing to use sanctions as a tool for influencing behavior when diplomacy alone is insufficient, the effectiveness of sanctions in achieving desired goals is hotly debated. Examining the effects of sanctions on Russia may inform us of the potential impacts of U.S. and Western sanctions on China.

The Russian economy has been severely impacted by sanctions in recent years, growing only by an average of 0.3% per year compared to the global average of 2.3% per year since 2014. It is hard to isolate the extent sanctions have contributed to this, however, as the imposition of sanctions coincided with a drop in oil price that happened in the last months of 2014.

That being said, Russia’s Finance Minister Anton Siluanov noted that sanctions and the drop in oil prices cost Russia $140 billion per year saying “we will lose around $40 billion a year because of sanctions, and around $90-100 billion a year if we assume a 30% drop in the price of oil.” A study by the IMF looking at Russia concluded that sanctions lowered Russia’s growth by 0.2% every year from 2014 to 2018. Other sources estimate a loss of 1% of annual GDP during 2014-2015 and 0.5%-1.5% of foregone GDP growth since the U.S. placed additional sanctions in August 2018.

Outside of the direct impacts, sanctions have also increased uncertainty for many Russian companies, making it harder to set a corporate strategy, which may have further economic consequences. In a hypothetical world where there are more severe sanctions against China, we can expect them to have a similar effect of increasing uncertainty and reducing China’s economic growth.

That being said, there are several key differences between imposing sanctions on China compared to imposing them on Russia. Primarily, China has a GDP of $14.34 trillion, which is significantly larger than the $1.7 trillion of the Russian economy. This means that it would be much easier for China to absorb the impact of sanctions imposed on it, and this difference is only expected to expand in the future. The different levels of economic integration with the U.S. and the West is another reason why sanctions will hit both countries differently. In 2019, Russia was America’s 20th largest supplier of goods with imports totaling $22.3 billion. In contrast, China was America’s 3rd largest trading partner with imports valued at $451.7 billion. The significant economic integration between the U.S. and China means sanctions against China will also have a much larger negative impact domestically.

The irony of sanctions is that while they may induce certain behavior in the short-term, this will also corrode their effectiveness in the long-term. Punitive sanctions will induce targeted countries and entities to look for alternatives and reduce their reliance on the sanctioning nation. For example, U.S. sanctions against Iran have led the country to turn towards Russia, China, and India. Thus, the more sanctions are used, the more targets will turn towards alternatives to insulate themselves against its future effects.

In the case of China, they are turning towards domestic companies, further accelerating the technology decoupling between America and China.

“China sees domestic tech development and innovation as both the defence and offense to potential US sanctions,” said Winston Ma, attorney, author and an adjunct professor of law at New York University School of Law. Ma’s recent book “The Digital War – How China’s Tech Power Shapes The Future of AI, Blockchain and Cyberspace” highlights the dramatic advances China has made in these tech fields, emerging from a “mobile economy” to a “digital economy”. Ma notes in the chapter, “The Tech Cold War”:

“China’s ambitions and progress have led to talk of an artificial intelligence arms race with the United States. Cross-border tech investments are increasingly viewed through national security lenses by the two countries. In recent years, more and more deals have been blocked, corporations sanctioned, and AI exchanges restricted. Hence, the digital economy is in a vital conflict and crisis: the global tech world, together with at least part of the world economy, has now fractured into two – and potentially more, considering Europe, Japan, and other regions – spheres of influence. Nations and companies around the world are being forced to choose sides in a conflict that is fracturing global supply chains and tech innovation.”

One area where this is currently playing out is in the semiconductor industry, which has traditionally been dominated by U.S. companies, with eighty percent of the chipmaking and design processes being carried out by American businesses. An investigation into ZTE found the company to have violated existing sanctions against North Korea and Iran. As a result, the company became the target of sanctions itself. Placed on the “entity list” also known to some as the “death penalty,” ZTE found itself unable to access key semiconductor components and announced that “as a result of the Denial Order, the major operating activities of the company have ceased.”

“Neck-choking” technology, such as semiconductor technology, are technologies where China is heavily reliant on America. These areas are considered by the Chinese government to be potential areas of weakness where the American government can potentially “strangle” or put pressure on China.

“The virtual monopoly on chip design and chip making equipment sectors has given the US vast powers to control the flow of technology to China, and the Chinese government is determined to be free of ‘neck-choking’,” says Ma.

This has led the government to invest aggressively in its semiconductor fund resulting in an unprecedented growth in the area. Over 22,000 new companies focusing on semiconductors were registered in China in 2020.

China’s growing sanctions regime

China sees domestic tech development and innovation as both the defence and offense to potential US sanctions.”

– Winston Ma

In addition to their negative economic impacts and the potential corrosion of their long-term effectiveness, another danger of over-reliance on sanctions in diplomatic relations with China is the potential for escalation. Unlike Russia, which has a limited range of response options, China has not hesitated to put retaliatory measures in place when it has been the target of sanctions.

Shortly after America imposed sanctions on China over its treatment of Uyghur minorities earlier last year, Chinese officials quickly announced retaliatory sanctions on July 13, 2020 against American officials and entities in a symbolic attempt to retaliate. A month later, China imposed additional sanctions on eleven individuals after America imposed sanctions on China for its erosion of Hong Kong autonomy.

Interestingly, China’s willingness to impose retaliatory sanctions has been a recent phenomenon. China is a relatively late participant in the sanctions landscape and actually opposed them in the past because it was often the target of such measures. Sanctions were once considered by China as a violation of sovereignty.

Despite the late entrance, however, China is already overseeing a rapid expansion of its sanctions regime, making a series of changes to its legal framework in response to the recent sanctions placed on it. China’s Ministry of Commerce (MOFCOM) first issued the Provisions on the Unreliable Entity List which establishes a formal mechanism for sanctioning individuals and entities. Afterwards, it passed the Export Control Law which establishes a comprehensive export control framework.

In January 2021, MOFCOM also published Rules on Counteracting Unjustified Extra-territorial Application of Foreign Legislation and Other Measures which allow Chinese authorities to punish companies with business in China for complying with foreign sanctions restrictions. Most directly in June 2021, China adopted the Anti-Foreign Sanctions Law (AFSL) which provides a legal basis for China to adopt retaliatory measures against “discriminatorily restrictive measures” that are imposed on it.

Responses to this new law have been mixed. Some commentators, for example, Political Economy Editor at South China Morning Post, Zhou Xin, have argued that the new law is a defensive move by Beijing to increase its legal arsenal in the face of sanctions threats by foreign governments. Others, however, have a more negative view. The European Union Chamber of Commerce President, Joerg Wuttke, noted that “Such action is not conducive to attracting foreign investment or reassuring companies that increasingly feel that they will be used as sacrificial pawns in a game of political chess.”

Whereas sanctions in America have a robust legal framework that involve multiple legal authorities and a process that is codified and published in the Code of Federal Regulations, China has yet to develop a comprehensive system. The Anti-Foreign Sanctions Law as it currently stands is broadly written, which has led to concerns in the business community. Additionally, the law contains wording that implicates “any organization and person” who comply with any foreign sanctions. For companies doing business in China, this means that they may be sued in China for complying with American export control rules. This may put businesses in a dilemma of choosing between complying with American sanctions or complying with Chinese laws.

Despite these developments, it is important to note that China has yet to blacklist foreign companies. As of now, China seems less focused on implementing restrictive sanctions measures and more on building its deterrent capabilities. Given the dominance of both the U.S. and Chinese economies, escalating sanctions between the two countries could have devastating consequences.

Finally, it is important to note the interests of other countries and how they could play a potential role. For example, countries like the UK are aligned with America in speaking out against China on issues such as human rights. However, they also need to engage with China on areas of mutual interest, which range from trade to climate change. For instance, China is an important partner for the COP26 climate summit in Glasgow this year. If sanctions continue to escalate, however, it may become harder and harder for these countries to balance their interests.

Conclusions?

While the use of sanctions as a tool of foreign policy will not be going away anytime soon, leaders should be careful in terms of their use because of the potential for escalation, especially as China is increasingly building out its capabilities on this front and has demonstrated a willingness to use them. We have already seen how this could play out in the trade war with China, which has cost America an estimated 0.3% of GDP and nearly 300,000 jobs. China’s increasing role and its aspirations to dominate and shape the world order mean it is much more emboldened to strike back.

Gloria Zheng, LIMA CHARLIE WORLD

[Edited by Anthony A. LoPresti]

Gloria Zheng is a Corporate Bank analyst at a European financial institution. Prior to this role, Gloria graduated magna cum laude from New York University, Leonard N. Stern School of Business, where she double majored in Philosophy and Business, with concentrations in Finance and Computing & Data Science. At NYU she completed her thesis titled “Corporate Venture Capital and Digital Disruption”. Gloria served as Co-President of the Stern Business and Law Association and President of the NYU Policy Debate team.

[Subscribe to our newsletter for free and be the first to get Lima Charlie World updates delivered right to your inbox.]

Lima Charlie World provides global news, featuring insight & analysis by military veterans, intelligence professionals and foreign policy experts Worldwide.

Support Lima Charlie’s quality journalism and independent voice! Our team at Lima Charlie World works hard to bring you in-depth & insightful news coverage. We believe in our mission to investigate and report the truth, with an eye towards promoting peace, understanding & positive political engagement … But our independent, investigative journalism takes a lot of time, money and effort to produce. If everyone who reads our work would make a small donation, we would be able to continue keeping you informed. Please take a moment. Thank you in advance for your kind support.

For up-to-date news, please follow us on twitter at @LimaCharlieNews

In case you missed it:

![Blossoming Russo-Turkish alliance leaves U.S., NATO behind [Lima Charlie News]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/Russia-Turkey-alliance-leaves-U.S.-NATO-behind-480x384.png)

![Image What exactly is the extent of Russia’s influence on North Korea? [Lima Charlie News][Photo: Yuri Kadobnov]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/What-exactly-is-the-extent-of-Russia’s-influence-on-North-Korea-1-e1557115659181-480x384.jpg)

To the Editor:

There is a growing body of evidence that the Magnitsky story as told by Bill Browder is an elaborate fabrication. Germany’s Der Speigel investigated Browder by following the evidence, and it did not support Browder’s allegations. The facts appear to tell a very different story. The Russian tax authorities had initiated an investigation in 2003 into Hermitage shell companies based in the region of Kalmirka, in which federal tax breaks for employing disabled Afghan War veterans, were allegedly being abused. The shell companies were stock holding companies, and the “employees” were employed for their stock market “expertise”, allegedly created by Magnitsky, for Hermitage Capital. Browder claims that the 2007 raids were the first thing he knew about it, when they had been twice court ordered in 2003 and 2004, to pay back taxes and fines amounting to $US40 million.

Browder was expelled in 2005 for what is believed to be illegal buying of Gasprom shares, only available to Russian citizens, and selling them to Western investors, via a certificate scheme for foreigners, valued over 200x the local shares. The fact that the Kalmirka investigation was ongoing for four years, would not have helped Browder’s case.

The local media broke the story of the Kalmirka investigation in 2006, and within a week of the 2007 raid, the reasons for the raid were stated, massive tax evasion. Magnitsky did not investigate any tax fraud, there is no documentary evidence. A third article in Kommersant on 3 April 2008, revealed that the shell companies had been re-registered in order to defraud the Russian government, as reported by a whistle blower Rima Starova. Browder claims Magnitsky went voluntarily to the police in June, when in fact, he was taken in for interrogation for his part in the Kalmirka tax evasion. When Browder tried to get ahead of the story on 4 April 2008, he never even mentioned Magnitsky, but a group of Hermitage lawyers, which we know from testimony Magnitsky was not. After Magnitsky’s arrest in Oct 2008, Browder simply left his legal defence to Firestone Duncan, Magnitsky’s employer. Remember Browder hadn’t been in Russia for over three years. When Magnitsky was asked after his arrest, if he knew about the whereabouts of Browder, he said he hadn’t seen or heard from him in over four years. There was no motive for “Russian Officals” to “murder” Magnitsky, he never accused the tax inspectors of the re-registration of the shell companies, while the perpetrators remain unknown, the authorities believe it was Browder himself. Magnitsky died in pre-trial detention in November 2009, from pancreatitis. He was never beaten by riot police with rubber batons, that is a Browder concoction, he was restrained when he became delirious shortly before he died.

The evidence strongly suggests Browder and his US APCO lobbyist Jonathan Winer, concocted the entire story in order to lobby the US Congress, who never found a story accusing Russia of some atrocity too good to be true. Browder’s self-serving story wasn’t “revenge” for Magnitsky, he could have had him released if he paid the back taxes, it was an elaborate scheme to ensure no Western country would extradite him to Russia, and no Russian investigators could travel to the West to attempt to recover funds that Browder had taken offshore.

The Man Behind the Magnitsky Act | 100 Reporters

Reporter: Lucy Komisar

https://100r.org/2017/10/magnitsky/

The Case of Sergei Magnitsky

Questions Cloud Story Behind U.S. Sanctions

Reporter: Benjamin Bidder

https://www.spiegel.de/international/world/the-case-of-sergei-magnitsky-anti-corruption-champion-or-corrupt-anti-hero-a-1297796.html

Naturally Browder complained about the Der Speigal article, Der Speigal stood by its investigation and published again:

Accusation from Investor Bill Browder:

Why DER SPIEGEL Stands Behind Its Magnitsky Reporting

“Former investor Bill Browder has accused DER SPIEGEL of having incorrectly represented the circumstances surrounding the death of the Russian Sergei Magnitsky. DER SPIEGEL rejects the criticism for the reasons we have outlined below.”

https://www.spiegel.de/international/world/spiegel-responds-to-browder-criticisms-of-magnitsky-story-a-1301716.html

Browder further complained to the German Press Board, the board found that Der Spiegel did not violate the press code of conduct, and found that the investigation had used reliable sources. The Board further said that Browder was not being truthful by continuing to call Magnitsky a “lawyer”, stating he never went to law school, he was not qualified as a lawyer, he was a tax accountant.

Der Speigel took much material from what became known as the “Prevezon Case”. Browder initiated a US Federal Case by passing “evidence” to US Attorney Preet Bharara in 2013, accusing Russian national Denis Katsyv of receiving some of the mythical $230m Russian tax fraud, ( and everyone up to Vladimir Putin ). Katsyv hired US Law Firm Baker-Hosteter to defend in what became a civil case. Three times they attempted to subpoena Browder, who ran away twice in Aspen, CO, but was caught in New York, after again running away from the process server. Browder was ordered to appear for a deposition on 15 April 2015. To say it was a disaster, is an understatement.

The 100 Reporters article goes into detail of this case, and the deposition, the official transcript is linked in the article, as are other documents from the case:

https://100r.org/media/2017/10/Browder-Deposition-April-15-2015.pdf

https://100r.org/media/2017/10/Magnitsky-Testimonies-Oct-2006-June-2008-Oct-2008.pdf

https://100r.org/media/2017/10/Dalnaya-Steppe-Trial-Court-Decision-Imposing-20-million-civil-penalty.pdf

The Magnitsky Act the original Russian, and the now world wide act, both violate the human rights of those sanctioned by the US government. No due process, some has merely to be accused, in the original act almost thirty Russians, mostly tax investigators, prosecutors and other officers were sanctioned on Browder’s word alone. One of the investigators sanctioned, Pavel Karpov, took Browder to court in the UK High Court, and while the Judge ruled that Karpov didn’t have a tort for defamation in the United Kingdom, he did rule that Browder had no basis to accuse him of any crime, let alone a part in the “murder” of Magnitsky. Karpov eventually got a small settlement against Hermitage from a Russian court. The sanctions have never been lifted.

In addition, the Danish financial finans.dk also began investigating Browder after he accused Danske Bank of, yes you guessed it, receiving some of the $230m tax fraud. By some accounts, it seems that well over $1 billion has been “received” in total across the planet.

Translation: Danske Bank and Nordea’s evil money laundering influence has a huge impact – but can you trust the man who has been sentenced to nine years in prison for tax fraud?

https://finans.dk/indsigt/ECE11243114/danske-bank-og-nordeas-onde-hvidvaskaand-har-enorm-indflydelse-men-kan-man-stole-paa-manden-der-er-idoemt-ni-aars-faengsel-for-skattesvindel/

Translation:Bill Browder has served as a money laundering expert for the European Parliament on the Panama Papers.

The Centre of the Scandal – Mossack-Fonseca also set up shell companies for Browder.

https://finans.dk/finans2/ECE11249056/bill-browder-brugte-selv-skattely-til-sine-selskaber/

Do I expect that your publication will retract the part of your story about the Magnitsky Act?

When hardly any English language publication has had the courage to the US Congress and UK Parliament?

But as we know all too much, as the China hysteria ramps up, that truth is the first casualty of war.

[Addendum: Despite his best efforts, Browder has failed for the third time to lobby the Australian government to pass a Magnitsky Act – the most recent attempt – “We will not introduce an individual sanctions bill with Magnitsky in the title”.]

I look forward to be surprised.

Dr. Brett Harris

Melbourne, Australia