Amid debate over the U.S., French, and UN troop presence in West Africa, the stability of an entire region is at stake as Mali’s citizens head to the voting booths to decide on a new government.

Mali has been in a defining state of low intensity conflict for over a decade, with a civil war erupting in 2012. This July 29th the stability of the entire West African region is at stake as Mali’s citizens head to the voting booths to decide on a new government for the first time in five years. The international community has paid dearly in blood and lives to get this far, and can now only watch and hope that nothing disrupts the election. Tensions remain high as even a stray round could destroy the fragile progress that has been made, causing renewed bloodshed throughout the region.

What Bad May Come

Mali once stood as a showcase of how an African country could develop into a democratic and stable country. Less than a decade ago, its future appeared bright. It was believed that Mali was on the fast-track to becoming a viable member of the world community. Yet, the emergence of al Qaeda and the resulting global war on terror would put an end to that.

Al Qaeda has long found Africa to be an ideal operating ground. Its founder, Osama Bin Laden, found a safe-haven in Sudan for a number of years in the mid 90s, and many of the original al Qaeda leaders have a past in the nuanced Egyptian Jihadist movements.

The country was on a successful commercial and educational trajectory during most of the 90s and early 2000s. This was as a result of its close ties to Europe, particularly France. Mali has been within the Franco-Belgian sphere of influence since it fell under French control during the late 19th century. It would eventually receive its independence on June, 1960. Despite this, the capital of Mali, Bamako, retained strong ties to Paris.

These successful commercial ties with the West resulted in a series of infrastructure projects, improved living standards, and wealth growth. Such developments, however, were centered around a small number of people, primarily in Bamako. Few improvements reached the more rural and impoverished areas, such as those north of Mali. This, combined with the country becoming increasingly more secular as a result of its Western ties, became part of the red hot embers that Salafist-Jihadist groups would come to agitate, using it to stir up civil disturbances.

The Embers of Chaos and the Dream of Azawad

With surrounding countries such as Niger, Ivory Coast, Liberia, and Sierra Leone all embroiled in deep conflict, often with foreign Jihadist groups such as al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) playing a central role, it didn’t take long for conflicts to spill into Northern Mali.

At first the conflicts came in the form of soaring border skirmishes, bandits overtaking villages, and Jihadist groups using Mali as a safe haven or a logistical hub. The central government often responded poorly to the plight of minority tribes, mostly electing to invest more in military responses than in infrastructure improvements in the area. As such, it didn’t take much for foreign groups to not just establish themselves by building good relations with local tribes and ethnic groups, but they would channel their resentment against the central government and use local movements as proxy militias on behalf of AQIM.

One such group of people in northern Mali that AQIM had particularly good relations with was the nomadic Tuareg people, a large Berber ethnic confederation whose inhabitations span a vast area from the Sahara in southwestern Libya to southern Algeria, Niger, Mali, Burkina Faso and even Nigeria. The Tuareg had been engaged in insurgencies against the Malian government since at least 1916.

The Azawad-aligned groups began receiving weapons from other Islamist groups consisting of Libyan stockpiles left after Colonel Gaddafi’s fall. Yet, the alliance was more technical than ideological, with the Touregs not sharing the Jihadists’ view of Islam.

The alliance would be short lived. AQIM would soon become a direct opponent of the Tuareg People and its MNLA ambitions. Yet, while AQIM had played a minor role in the initial launching of the rebellion, its presence as a destabilizing element and its access to modern arms was crucial towards facilitating the launching of offensives. The alliance gravely damaged the central government’s ability to combat threats within its own borders.

Mali was quickly finding itself in a security vacuum outside of the capital, and the Western-backed local military came under increasing strain to fight a war it could not win. As a result, Mali’s military leadership gained additional political powers, and engorged themselves on bribes while creating their own private de facto kingdoms within the military. This was often at the expense of frontline outfits and lower ranking officers’ abilities to carry out the missions they were handed.

The situation reached its pinnacle when, on March 21st 2012, a group of mutinying Malian soldiers attempted a coup d’etat that destabilized the central government in Bamako, and forced the Malian President Amadou Toumani Touré into hiding.

This would push Mali over the edge. The embers of a civil disorder soon turned into a firestorm of civil war.

![Image Leader of the coup against Mali President Amadou Toumani Touré, Captain Amadou Sanogo (2-R) walks with members of his staff at the Kati military camp near Bamako, Mali, 02 April 2012. [EPA]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/Amadou-Haya-Sanogo.jpg)

Re-Enter the French

Before long, France stepped in with its military might. In what was codenamed Operation Serval, France, under the guise of fighting the rebels and jihadists in the north, ordered elements from the French Foreign Legion (FFL)’s Special Operations forces to board Air Force C130s to take them to Mali. Along with the FFL units came supportive troops, and air-to-ground capabilities in the shape of Mirage and Rafael fighter jets.

All in all, France would deploy over 2,000 troops to Mali in March of 2013. Their mission, in addition to the Western sanctioned notion of fighting Islamist militia groups anywhere they could be found, was to safeguard the continuation of a French-backed government in Mali.

![Image French soldiers from Operation Barkhane stand outside their armored personnel carrier during a sandstorm in Inat, Mali, May 26, 2016 [Photo Media Coulibaly - Reuters]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/Mali-French-SF-Photo-Media-Coulibaly-Reuters.jpg)

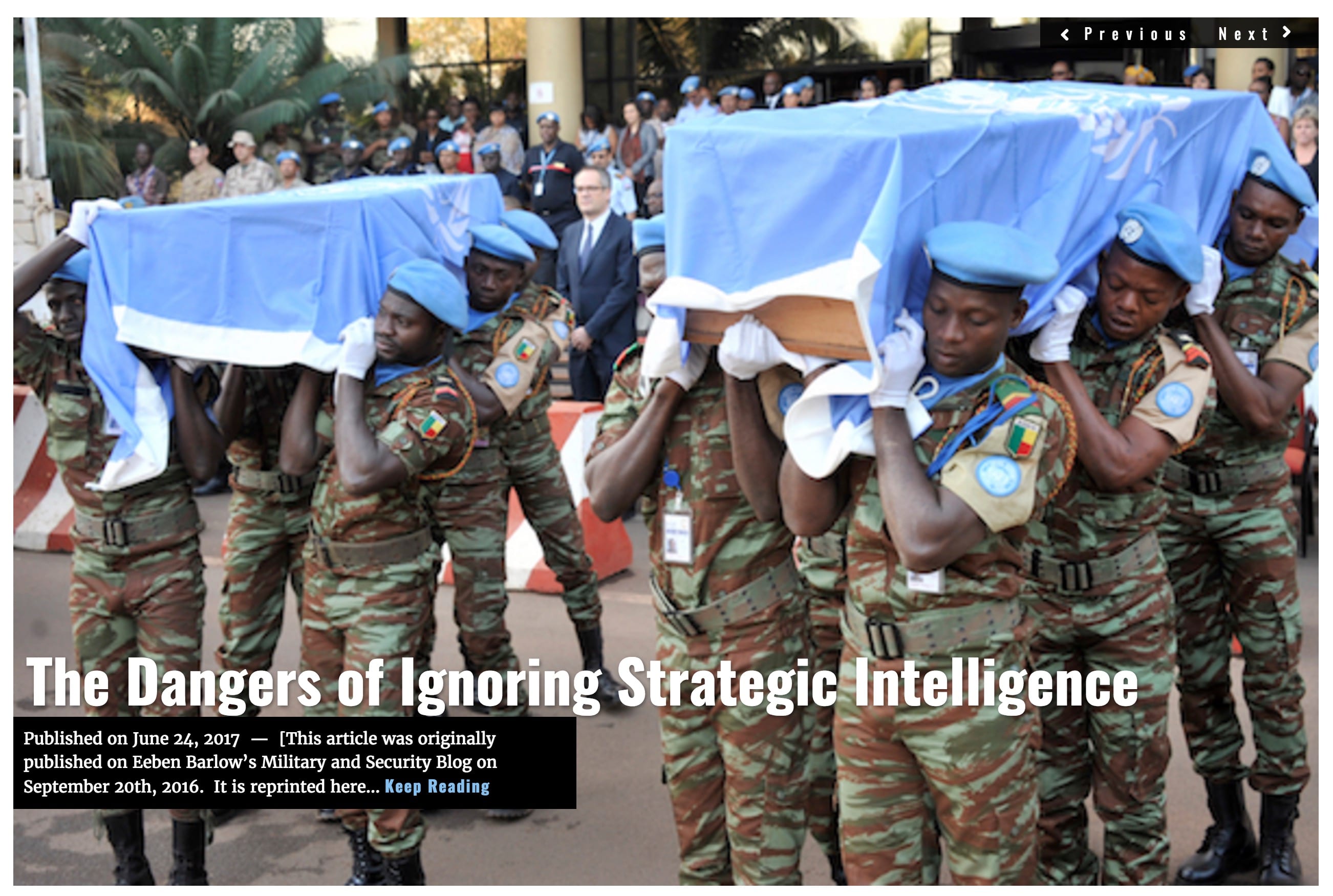

Operation Serval was eventually merged into an international community response, which began with the Germany and the U.K sending supporting troops in mid 2013. The European military presence was then, with U.S. support, converted into a United Nations (UN) mission by autumn 2013. As the opposition sees UN personnel as an extension of the French, and ultimately the central government, UN peacekeepers have quickly become prime targets.

As of the time of writing, the Northern Mali conflict has been overtly ongoing for 6 years and 6 months. It is showing no signs of slowing down.

What Good May Come

A multitude of occasional ceasefires – usually to enable all sides to regroup and gather more munitions – have done little to halt Mali’s steady decline and the destruction of its social fabric. As a result, Mali has become one of the most dangerous places in Africa, and one of the most treacherous for the UN to operate in.

For instance, in April the international UN camp in Timbuktu was attacked by a local jihadist group. The battle for control of the outer perimeter of the camp raged for hours before reinforcements could arrive and the marauders could be pushed back. The attack left one UN soldier dead, and thirteen injured. Just a few days earlier, a grenade attack in northern Mali left two UN soldiers killed and several injured. What began as a sweetheart position for UN personnel, something to be used as a reward for services rendered, is now a penalizing and brutal station that few dare volunteer to.

Solutions to the conflict appear increasingly distant. This despite a fragile, pseudo functional peace agreement negotiated with the support of France in June 2015. As part of the agreement, the nation was set to hold a national election, observed and organised by the international community, in the shape of the UN. Other aspects of the agreement had the remains of the Western-backed central government promising to vest heavily in healthcare, schools and water wells in the northern areas.

These promises, however, remain unfulfilled, with the failure to implement them used as building blocks by militia oppositions to create a populist movement in their support.

Despite the best intentions, the upcoming presidential election will no doubt attract more problems than it aims to resolve. While the election should create a sense of national unity, it appears rather likely to become a vehicle to hasten the dissolve of Mali’s societal fabric. Local and regional elections were postponed twice due to security concerns, until they were finally carried out, in part, on April 1st. That election in turn was part of what led to a surge of violence against UN personnel.

With the security situation deteriorating, and the fact that neither the government nor the UN will be able to safeguard against terror attacks against individuals and voting stations, it is fairly obvious that turnout will be a concern. If voter turnout is too low, the election will be in practice null and void due to legitimacy concerns. This in turn could create a power vortex that may disrupt not just Mali’s internal situation, but further inflame the neighbouring situations.

A second problem with the upcoming election is that due to the disruption in government provided services, many young people who have recently turned eighteen have no identity cards, and have not been informed how to register to vote. This situation is further compounded by the fact that many Malians still remain in refugee camps in border countries, having fled the unrest which began in 2012. This means that a significant portion of the population will not have the option to vote.

A Certain Uncertainty

These problems notwithstanding, Mali’s national reconciliation minister, Mohamed El Moctar, remains convinced that the election will be conducted. Mali is, the minister argued, a democratic nation. The minister also said he hopes more of his countrymen will make the hazardous trip through bandit and rebel held territories, across the border, to get back to Mali in time to participate in the election. At worst, the minister said, in some cases ballot boxes might be able to be brought to some refugee centres. This solution has however been criticized by international observers, as it would make it significantly more difficult to detect and combat attempts of election fraud.

The UN Security Council has expressed grave concerns over the situation, but admits it has little to offer except for the existing troop presence, and additional observers.

Even if the election is carried out to its promised conclusion, a main problem will remain – how to get representatives from all regions to not just agree to create a functional coalition government, but to honor the outcome of the election.

While the cause of the conflict in Mali is incredibly multifaceted, the most common explanation is that it reflects upon the longstanding friction between ethnic and sub-tribal groups in the southern and northern parts of the country.

With the civil war having entered its sixth year, showing little sign of ebbing, it appears almost certain that the election on July 29th will not only have tremendous repercussions throughout the region, it will not go according to anyone’s plan.

John Sjoholm, Lima Charlie News

[Edited by Anthony A. LoPresti] [Main Photo: Baba Ahmed / AP]

John Sjoholm is Lima Charlie’s Middle East Bureau Chief, Managing Editor, and founder of the consulting firm Erudite Group. A seasoned expert on Middle East and North Africa matters, he has a background in security contracting and has served as a geopolitical advisor to regional leaders. He was educated in religion and languages in Sana’a, Yemen, and Cairo, Egypt, and has lived in the region since 2005, contributing to numerous Western-supported stabilisation projects. He currently resides in Jordan. Follow John on Twitter @JohnSjoholmLC

Lima Charlie provides global news, featuring insight & analysis by military veterans and service members Worldwide.

For up-to-date news, please follow us on twitter at @LimaCharlieNews

In case you missed it:

![Image Mali's election - West Africa hangs in the balance over a peace that never was [Lima Charlie News][Photo: Baba Ahmed / AP]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/Malis-election-West-Africa-hangs-in-the-balance-over-a-peace-that-never-was.png)

![Africa’s Elections | In Malawi, food, land, corruption dominate [Lima Charlie News]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/Malawi-election-Food-land-corruption-480x384.jpg)

![Image The Rwandan Jewel - Peacekeepers, Conflict Minerals and Lots of Foreign Aid [Lima Charlie World]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/Rwanda-Jewel-480x384.jpg)

![Image [Women's Day Warriors - Africa's queens, rebels and freedom fighters][Lima Charlie News]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/Womens-Day-Warriors-Lima-Charlie-News-480x384.jpg)

![Image Zimbabwe’s Election - Is there a path ahead? [Lima Charlie News]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/Zimbabwe’s-Election-Is-there-a-path-ahead-Lima-Charlie-News-480x384.png)

![[Silver lining for China in Zimbabwe’s violent elections][Lima Charlie News]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/Screen-Shot-2018-08-02-at-12.51.35-PM-480x384.png)