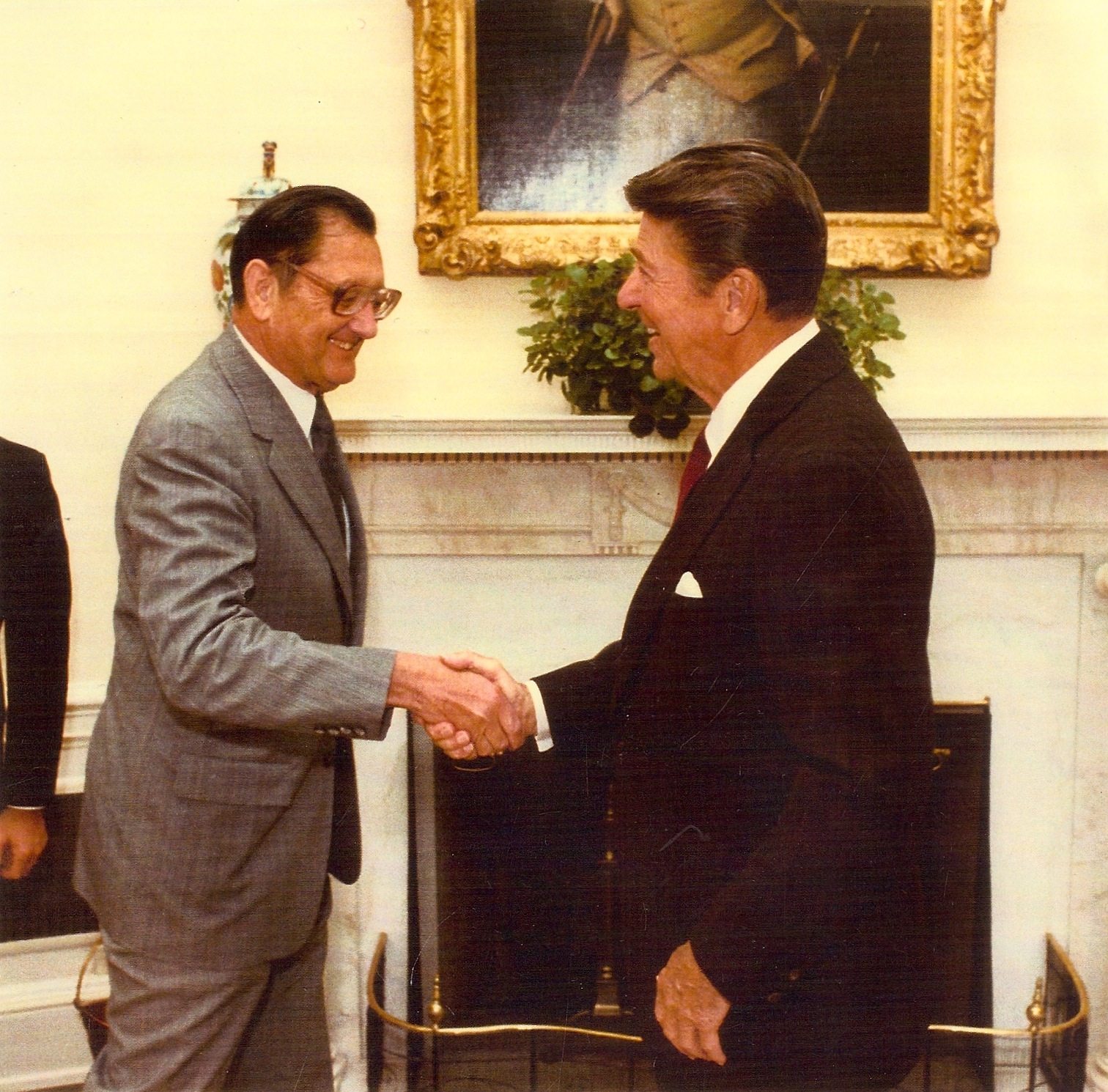

Former Ambassador and Lt. Gen. Edward L. Rowny, who graduated from West Point in 1941, served in three wars (World War II, the Korean War and Vietnam), was as an advisor to five presidents and was one of President Reagan’s key architects of the policy of peace through strength, and Chief Negotiator for Nuclear Disarmament with the Soviets, died Sunday at 100 years of age.

Gen. Rowny, born in Baltimore, Maryland on April 3, 1917, was of Polish descent. His father had emigrated from Poland, and his mother, born in the United States, was also of Polish descent.

As reported by the Fund for American Studies (TFAS), in 2004, Gen. Rowny had joined with TFAS to launch the Paderewski (now the Rowny Paderewski) Scholarship Fund, enabling students from Poland to attend a TFAS summer institute in Washington, D.C. The scholarship fund is “dedicated to [Jan] Paderewski’s philosophy that freedom and democracy are enhanced through education and the arts.” Ignacy Jan Paderewski, a famous composer and pianist, was also Poland’s first Prime Minister (1918-1921). In 1992, Gen. Rowny fulfilled a fifty-year ambition to return the remains of Paderewski to Poland.

Gen. Rowny commanded troops in World War II, Korea and Vietnam. In WWII his men fought the Germans up the Western coast of Italy until the end of the war, before he was assigned to planning the invasion of Japan.

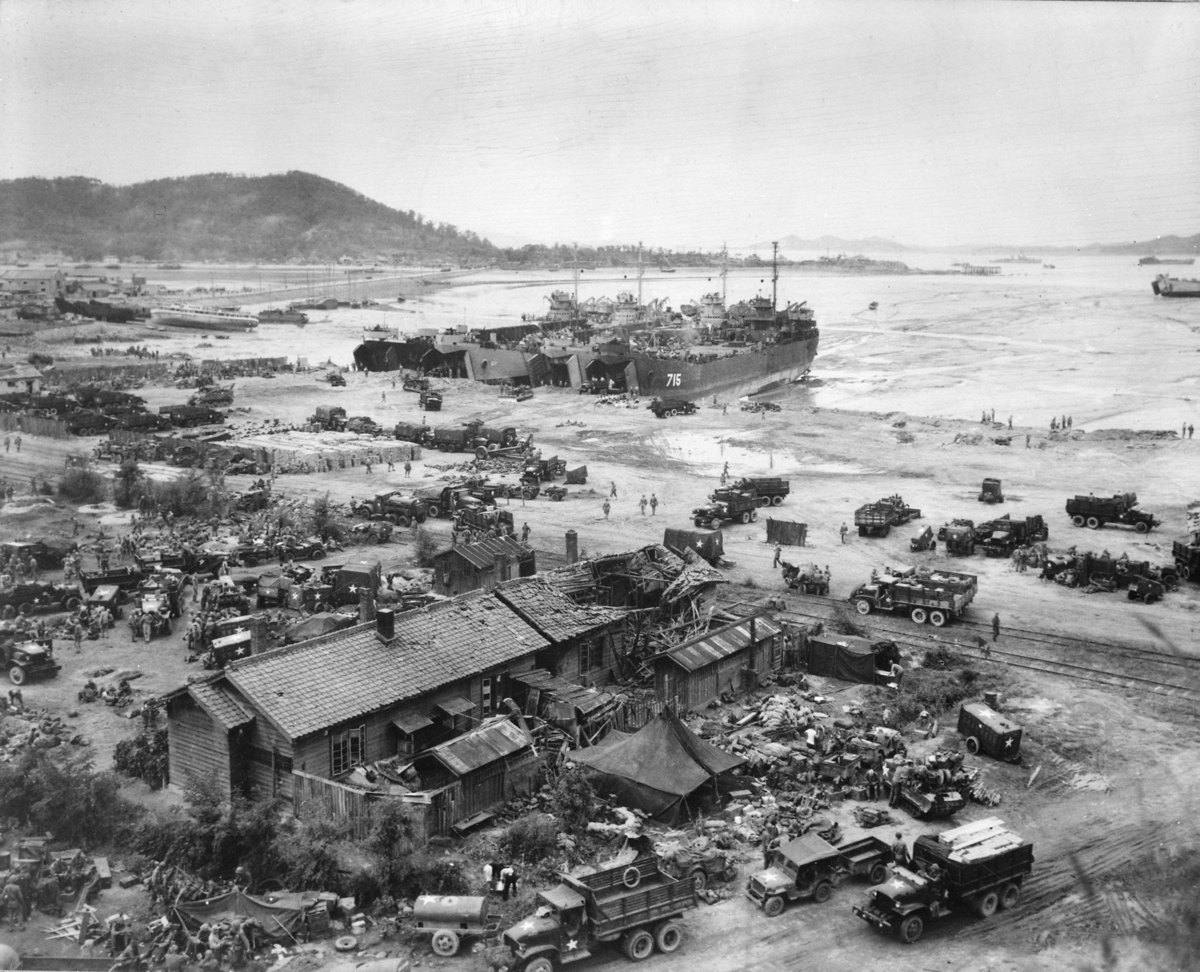

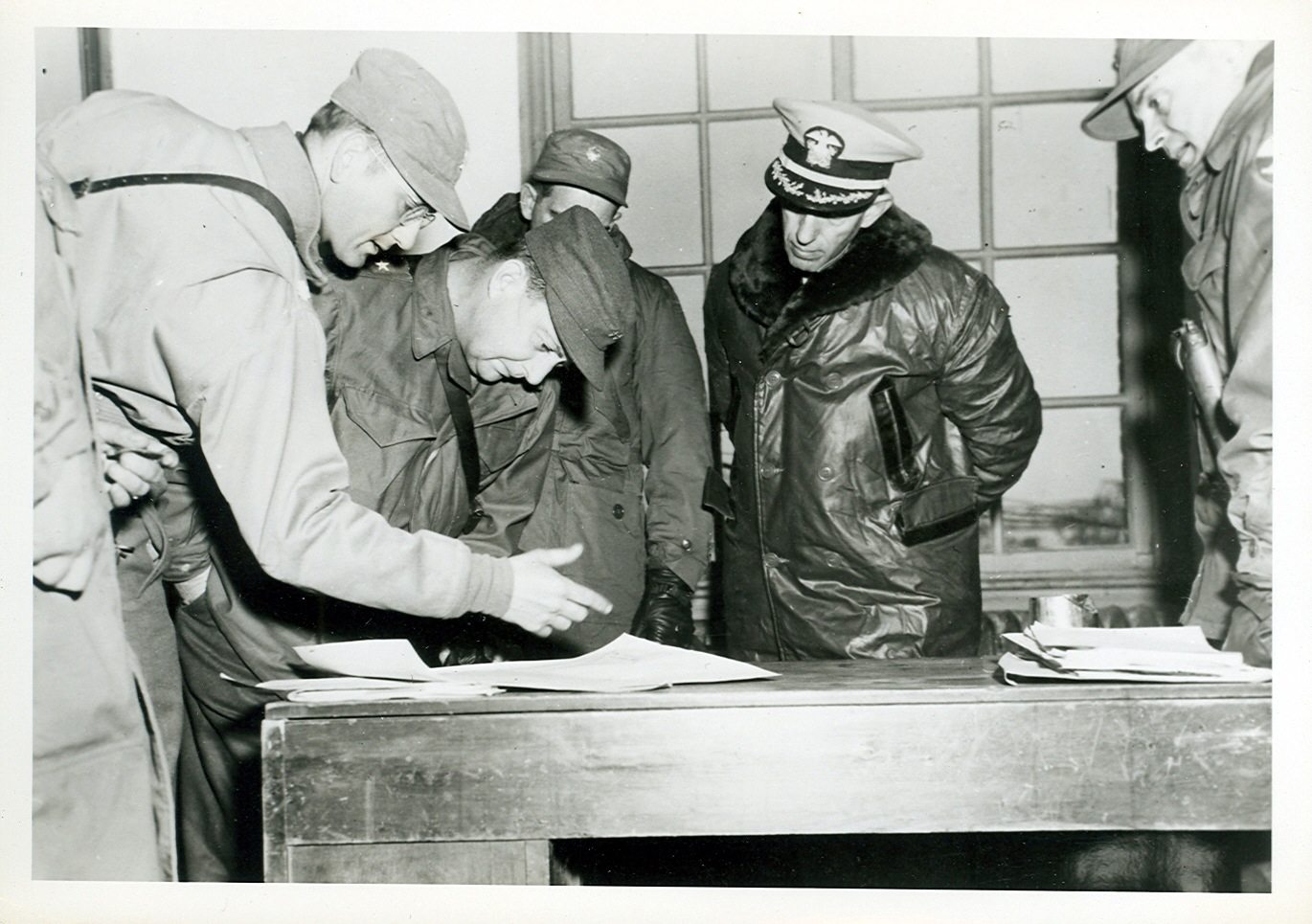

In Korea he was assigned to General Douglas MacArthur, becoming his spokesman and one of the planners of the landing of Inchon (September 15, 1950), which forced a North Korean retreat and enabled the taking of Seoul. Gen. Rowny oversaw the rescue of U.S. Marines and Army troops at the Chosin Reservoir, and his efforts led to the rescue of one hundred thousand North Koreans who wished to join South Korea. Beginning with the Korean War and into the Vietnam War, Gen. Rowny formed the foundation for the concept of Air Mobility, i.e. arming helicopters, that would later develop and change the face of war.

In 1971, Rowny was appointed the US representative to Strategic Arms Limitation Talks (SALT) and held this post under three presidents: Nixon, Ford and Carter. Under President Ronald Reagan, Gen. Rowny was appointed to the rank of Ambassador as the President’s chief negotiator on Strategic Nuclear Arms (START), and Special Advisor on Arms Control. Awarded the Presidential Citizen Medal, Rowny was credited as “one of the chief architects of peace through strength.” Gen. Rowny continued as President George H.W. Bush’s special advisor for arms control for the first two years of his term, before retiring from government in 1990 after fifty years of service.

Gen. Rowny then became a consultant, advising administrations and the Congress on national security matters and combating terrorism, which he continued before his death.

Gen. Rowny has five children from his former wife, Mary Rita, who died in 1988, before he remarried to Elizabeth Ladd in 1994.

The following is Gen. Rowny’s OpEd for Lima Charlie News, published May 20, 2017, in its entirety.

Lt. Gen. (ret.) Edward L. Rowny, a Commander in the Korean War and General MacArthur’s Spokesman, having also served as Chief Negotiator for nuclear disarmament with the Soviets, takes a look forward and back at the ongoing conflict in Korea.

The United States faces a difficult problem in Korea. When I served as Chief Negotiator for the US on strategic weapons during Soviet negotiations, the problem was also difficult. We had to convince the Soviets that our military strength was designed to deter and not promote a strategic war. Yet, the problem of dealing with the Soviets was easier than that with the North Koreans because the Soviet leaders, while tough, could be counted upon to be rational. There is little evidence that in Kim Jong Un we are dealing with a rational individual.

Yet, we need to try to solve the problem diplomatically because a military solution means the deaths of tens of millions of South Koreans in artillery range of North Korea. In my opinion, the diplomatic solution can be best achieved by stronger efforts by the Chinese leaders. They, too, face a delicate situation. However, I believe they can do more to bring about rationality in North Korea without risking a military confrontation.

I would like to reflect on several lessons I learned from negotiating with the Soviets.

The first is that we must always remain militarily strong. After World War II we demobilized our military too rapidly, thus giving the Soviets the impression that their puppet states such as North Korea could succeed in defeating their fellow countrymen to the south. Between the end of WWII and the beginning of the Korean War, the Soviets not only maintained a military lead over the US but supplied their allies such as North Korea with more modern equipment and provided them with better trained advisers. It was only through a combination of great sacrifices of US and South Korean soldiers and brilliant strategy such as the Inchon Invasion that we were able to save South Korea from being defeated by the North Koreans and Chinese forces.

A second and related lesson in dealing with the Soviets was that a combination of our naval superiority and brilliant diplomacy prevented the outbreak of war during the Cuban Missile Crisis. The White House assembled a group of brilliant and responsible strategists, led by Harvard Professor Graham Allison, who advised President Kennedy on a day-by-day basis on how to convince Nikita Khrushchev to turn around the Soviet ships carrying atomic missiles.

A third related lesson was President Reagan’s peace through strength policy. When the president began his first term, he decided to build up US nuclear weapons’ strength. His entire cabinet, with the exception of Secretary of Defense Casper Weinberger and CIA Director William Casey, advised against the buildup. They argued that the US was facing double digit inflation and unemployment and could not afford a buildup. Reagan countered that his main responsibility as president was to defend the security of the US. He succeeded in adding to the number of strategic nuclear weapons which, in turn, gave us sufficient strength to find leverage with the Soviet Union.

Why Korea was Divided at the 38th Parallel

I will not recount the events of the Korean Conflict here since they are adequately covered in my books, It Takes One to Tango and Smokey Joe & the General. However, I would like to highlight a number of little known facts.

The first deals with the selection of the 38th Parallel to mark the division between North and South Korea following WWII. Before the end of the war, General George Marshall asked his Strategic Planning Division (SPD) to recommend where the line should be drawn. One of the members of SPD, Col. Dean Rusk, who later became secretary of state, said that the obvious line of demarcation should be the 39th parallel since it was at the narrowest part of the peninsula, known as the “Wasp Waist,” and hence the easiest position to defend. Brigadier General George Lincoln, the head of SPD, said that the line should be drawn at the 38th parallel. He argued that the 38th parallel had been made famous in history by Yale geographer Nicholas Spykman. Spykman had written a book stating that 90% of the world’s best literature and inventions were created and most of the world’s great leaders were born north of the 38th Parallel. “Everyone knows about the 38th parallel but no one has heard of the 39th,” said Lincoln. We all objected but General Marshall, who highly regarded Lincoln, deferred to him. And so the 38th parallel divides North and South.

Saving the Marine Corps

Another relatively unknown story from the Korean Conflict was the fact that the Inchon Invasion saved the Marine Corps from oblivion. The Inchon Invasion, of course, was the amphibious landing of US troops into the Port of Inchon in proximity to Seoul. The challenges to such an invasion included typhoon season, 32-foot tides and 30-foot walls protecting the port. After General Douglas MacArthur convinced the Joint Chiefs of Staff that he be allowed to make the Inchon Invasion, the next major challenge was to find a division of ground troops to accomplish the task.

General Edward “Ned” Almond, MacArthur’s chief of staff, invited his Virginia Military Institute classmate, General Lem Shepard, head of the Marine Corps troops in the Pacific, to his Tokyo office. Almond talked to Shepard about what they both already knew, that President Truman had several months earlier written an order to the secretary of defense ordering that the Marine Corps be dissolved since it was no longer needed for amphibious landings. Almond suggested that Shepard make a quick tour of the US to appeal to Marine Corps reservists from WWII to volunteer to return to active duty. Within several weeks, General Shepard succeeded in raising the extra division of Marines needed for the invasion. The Inchon Invasion was a great success, raising the prestige of the Marine Corps. Faced with certain opposition by Congress, Truman rescinded his order that the Marine Corps be dissolved.

There is also a story, dear to my heart, of how I became engineer of the Army’s X Corps following MacArthur activating that Corps for the invasion. General MacArthur said he wanted me to become the Corps engineer. I told him I was flattered but this was not possible because I was only a lieutenant colonel and the position of Corps engineer called for a brigadier general. “No Problem,” said MacArthur. Picking up a pen he wrote, “Effective immediately, LTC Rowny is named X Corps engineer with the rank of brevetted brigadier general.” I know of only one other time when an officer was brevetted as brigadier general. This occurred during the American Revolution when General George Washington promoted Colonel Thaddeus Kosciuszko, his Polish engineer, to the elevated temporary rank.

I wish General MacArthur could really walk on water.

_____________________________________

As commander of the X Corps engineers, I oversaw the building of a bridge across the Han River to allow US forces to advance, following the Inchon Invasion, and recapture Seoul. This bridging proved difficult for several reasons.

First, the Han River was so wide that we lacked enough floating bridge equipment to span it. We had to take along forging equipment to construct fasteners that would link together three available types of bridging—50 pontoons in all. Second, the Han River was tidal, which required us to anchor the pontoons in both directions to keep them in place as the direction of flow reversed.

Third, General MacArthur wanted the bridge completed within ten days following the Inchon landing to permit President Syngman Rhee to re-enter Seoul on the three-month anniversary of the invasion of South Korea. This required us to begin bridge construction before securing the opposite, northern shore. That violated standard river crossing tactics and resulted in the death of several engineers who came under enemy fire. Still, we succeeded in completing the bridge just hours before the motorcade transporting General MacArthur and President Rhee crossed the river and entered Seoul. In a daily letter, I commiserated to my wife, writing, “I wish General MacArthur could really walk on water.”

Rescue at the Chosin Reservoir

Several other stories not well covered in the history books have to deal with my work as X Corps engineer, including how I built an airstrip at the Chosin Reservoir. The 1st Marine Division and elements of the 7th Army Division were surrounded by the Chinese at Chosin, which was a long lake elevated upon a plateau north of Hungnam. We needed a runway for C-119 aircraft to bring in supplies and evacuate the wounded, but it was in the middle of winter with sub-zero temperatures and frozen ground. To smooth a landing field, my plan was to erect two tents placed 5,000 feet apart at the flattest part of the plateau. The tents would allow bulldozers to be heated within and make successive runs from one tent to another as they progressed in clearing a landing field.

When the hot dozer blades scraped the frozen earth, however, the earth thawed but then stuck to the blades. I asked my staff to find a solution to prevent earth from dulling the blades. They experimented with various types of lubricants but found only one that worked—applying ski wax to the dozer blades. So I requested that several hundred pounds of ski wax be dropped by parachute into the perimeter. The scheme worked well but I was nevertheless criticized in a story in the Pacific Stars and Stripes. The article said I was wasting taxpayer money by dropping ski wax to soldiers to be used for recreational purposes, as though there was any time to ski when we were trying to rescue troops. Applying ski wax to the dozer blades did succeed in helping to evacuate hundreds of wounded Marines and soldiers. It also permitted the delivery of thousands of rounds of artillery and mortars.

A second major challenge at Chosin was to build a bridge across the precipitous chasm at the shore of the reservoir’s dam. A bridge was the only way out for US forces withdrawing, but the chasm spanned up to 100 feet in width. To cross it, I had my engineers construct and dismantle a bridge into segments that I planned to drop by parachute out of a plane into the Chosin perimeter. Pilots feared, however, that dropping such a heavy load would cause them to lose control of a plane. Fortunately, we found a brave Air Force pilot who believed he could control his aircraft as the bridge went out the rear door. After proving this could be done in experiments, he successfully dropped the bridge segments into the perimeter. Marines assemble the bridge and pushed it over a fulcrum to span the chasm. Although this was done under fire, the operation was quite successful.

Next, I had to protect the flanks of the column of Marines and soldiers descending from the plateau. I was also charged with out-loading troops and equipment on to ships in Hungnam harbor for evacuation to the southern tip of Korea. I then blew up the harbor so it could not be put to use by the Chinese or North Koreans.

Christmas Cargo

As we were completing the remainder of the out-loading process on Christmas Eve, I was approached by Colonel Edward Forney, the Marine Corps officer assisting me with the evacuation. He had in tow a Korean officer, Dr. Hyun Bong Hak, who had received a medical degree in the US. Dr. Hak had a proposal. He wanted to evacuate 100,000 North Koreans who feared for their lives if captured by the Chinese.

I had been ordered, however, to leave nothing of value for the rapidly approaching Chinese military. Our ships were overloaded with no room for North Korean refugees. Still, Col. Forney, Dr. Hak and I took the proposal to General Almond. Forney argued that saving the lives of North Korean civilians was more important than some less valuable equipment. General Almond agreed and we made room for the 100,000 men, women and children aboard the US troop ships. They were squeezed in and around tanks and equipment into every nook and cranny on the ships. Two days later the refugees, known as the Christmas Cargo, landed in Pusan to the south. Two civilians died in transit but two were born during the voyage.

At about 3 p.m. that same day, the only people remaining ashore at Hungnam’s harbor were my jeep driver, my radio operator and me when disaster struck. The skiff which was to evacuate us blew up, and my radio was not working. Admiral Doyle, Commander of the USS Mount McKinley, believed we had gone down with the skiff and set sail for the south.

Meanwhile, the Chinese had surrounded the Hungnam port and the city and were closing in. My resourceful jeep driver spotted powdered milk and suggested that we use it to spell out S-O-S in six-foot-tall letters on the black asphalt at the Hungnam air strip. The idea worked and an Air Force reconnaissance plane landed long enough for us to scramble aboard. As we were taking off, the Chinese hit the tail end of the plane but failed to cause any real damage. Two hours later, we landed at Tachikawa Air Base near Tokyo and shortly after that, with my radio operator and jeep driver as guests, we showed up at my quarters in Tokyo where my wife was preparing a Christmas Eve dinner. My children believed that I had come home to act as Santa Claus.

I received a call from General Almond on Christmas day. He said he was glad I was alive and wanted me to return to Korea the next day. I told him that was my wedding anniversary and asked if I could stay in Tokyo another day. The general said, “OK” but added, “Remember, Rowny, there’s a war going on.”

Upon returning to Korea, I was greeted with three surprises. The first was that Col. Aubrey Smith, the X Corps G-4 (logistics chief), had been murdered on Christmas day by his wife, who found him in bed with a Japanese maid. The second surprise was that General Almond designated me to replace Smith. I complained that my training was in operations and not logistics. “No matter,” said General Almond. “There are times when logistics overrides operations and this is certainly one of them.” The third surprise was that General Marshall designated General Matthew Ridgway as 8th Army Commander to replace General Walton Walker who had been killed in a jeep accident.

Wrong Way Ridgway

General Ridgway assembled the three Corps Commanders, i.e. I, IX and X Corps, and asked each for recommendations on the future operations of 8th Army. The I and IX Corps commanders recommended we evacuate Korea and return to Japan. The commander of X Corps recommended that the 8th Army stay in Korea and when ready, attack to the north. It took General Ridgeway 15 minutes of consultation with the commanders before he returned his decision. Grasping a grenade on his chest with his left hand, he thrust his right hand out and pointed it north saying, “Gentlemen, we’re going that way!” The staffs of the I and IX Corps groaned and shouted, “Wrong way Ridgeway” while we of the X Corps applauded.

In mid-March, as we were moving north, General Almond told me that if I volunteered to stay in Korea for a second year, he would assign me command of the 38th Infantry Regiment. I readily agreed and in June 1951 became its Deputy Commander. In September my commander, Col. Frank Mildren, allowed me to plan and execute the taking of Hill 1243 to the flank of Heartbreak Ridge, which had become famously known because of the difficulty in capturing it. My plan was to have large quantities of mortar and rocket ammunition hand-carried to three lower hills surrounding Hill 1243.

Since the steep hill did not permit the employment of tanks or artillery, I had every available non-infantry soldier, including cooks and clerks, lead teams of Korean ammunition carriers to the fire bases. Four US soldiers led 1000 of these Korean civilians, known as Korean Augmentation to the United States Army (KATUSAs), in carrying the ammunition on their backs to the three hilltops. It took approximately 5 hours to carry a 100-pound load up and three hours to return. The weary then rested for 8 hours and repeated their climbs.

By doing this for three days and two nights, through a lot of exhaustion and bloody feet, we amassed enough ammunition to deliver a barrage on Hill 1243. Between the massive firepower—approximately six times greater than typical—and the bravery of a Dutch Battalion in my regiment that led the charge, the attack was a resounding success. It resulted in the killing or wounding of hundreds of North Koreans, whereas we suffered only a dozen or so wounded. I was very proud that we took the hill without a single fatality on our side.

Early Concept of Helicopter Air Mobility

Another significant accomplishment was the surprise helicopter attacks I orchestrated against the North Koreans and Chinese using Marine Corps transport helicopters and my regimental soldiers. These attacks may not have been the first use of armed helicopters in combat, but they were certainly among the earliest on record. The raids formed a firm foundation for the concept of Air Mobility, i.e. arming helicopters, that would later develop and change the face of war.

In May 1952, having served six months as Regimental Commander of the 38th Infantry Regiment, I reluctantly relinquished command. Commands of combat units were highly sought after and regimental commanders were allowed to serve only six months in that capacity. I transferred from the Corps of Engineers to the infantry and became an instructor at the Infantry School at Fort Benning, Georgia.

Now, here it is six decades later.

Reflecting back on all that has happened in Korea, it’s hard to imagine that in all this time since, we have failed to reach an agreement to terminate the Korean Conflict. I see an urgent need to increase diplomatic efforts since the passage of time allows North Korea to perfect its nuclear ballistic missiles of intercontinental range. I believe that now is the time to convince other nations, especially China, to apply sufficient pressure on North Korea to halt their missiles testing program.

Lt. Gen. Edward L. Rowny, for Lima Charlie News

Former Ambassador and Lt. Gen. Edward L. Rowny, who graduated from West Point in 1941, served in three wars: World War II, the Korean War and Vietnam. He was as an advisor to five presidents and was one of Pres. Reagan’s key architects of the policy of peace through strength. In addition to serving as Chief Negotiator for Nuclear Disarmament with the Soviets, he helped originate the concept of armed helicopters, which he introduced to Vietnam in tests in 1962.

[Edited by: Anne Kazel-Wilcox]

[Main Image: Lt. Gen. Edward L. Rowny receiving Legion of Merit from General Edward “Ned” Almond, Gen. MacArthur’s chief of staff, Korea, 1950]

Anne Kazel-Wilcox is author of West Point ’41: The Class That Went To War and Shaped America, which she wrote in collaboration with seven U.S. Army generals. The book follows the West Point class of 1941 through three war – WWII, Korea and Vietnam – as well as through the Cold War and periods of peacetime military innovation. Her spouse and co-author, PJ Wilcox, served for more than 20 years in intelligence and in the U.S. Marine Corps. Anne can be reached by email (akazel@unsealedbooks.com).

Gen. Rowny’s exploits in the Korean War are detailed at length in his book Smokey Joe & The General which was edited by Anne Kazel-Wilcox.

Lima Charlie provides global news, insight & analysis by military veterans and service members Worldwide.

For up-to-date news, please follow us on twitter at @LimaCharlieNews

![Image Kim Jong-Un isn’t as crazy as you think [Lima Charlie News][Image: Reuters]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/Kim-Jong-Un-isn’t-as-crazy-as-you-think-480x384.png)

![Image North Korea mistakes: how Trump can overcome the shortcomings of Clinton’s 1994 Agreement [Lima Charlie News]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/North-Korea-mistakes-how-Trump-can-overcome-the-shortcomings-of-Clinton’s-1994-Agreement-480x384.png)

![Image Memorial Day may soon be a remembrance of democracy and those who had the courage to defend it [Lima Charlie News]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/Memorial-Day-may-soon-be-a-remembrance-of-democracy-and-those-who-had-the-courage-to-defend-it-Lima-Charlie-News-480x384.png)

![The Mind of Bolton - AUMF and the New Iran War [Lima Charlie News]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/Inside-the-mind-of-Bolton-Lima-Charlie-News-main-01-480x384.png)

![Image Kim Jong-Un isn’t as crazy as you think [Lima Charlie News][Image: Reuters]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/Kim-Jong-Un-isn’t-as-crazy-as-you-think-150x100.png)