“Please. I’m pregnant, and we won’t survive there,” pleaded a Venezuelan woman standing on a bridge that stretches between the northern Colombian city of Cúcuta and Venezuela.

“I’m sorry, honey, but you need to go back,” said a Colombian female police officer, sending the sobbing woman back into Venezuela.

These interactions have become a daily ritual for the police in Norte de Santander, Cúcuta, which deports roughly 100 Venezuelans a day, according to a report in the Chicago Tribune. In the second half of 2017, around 210,000 Venezuelans fled to Colombia, and, with 340,000 already in the country, Colombian officials are struggling to provide food and medicine to the refugees. In February, they changed course and implemented immigration restrictions.

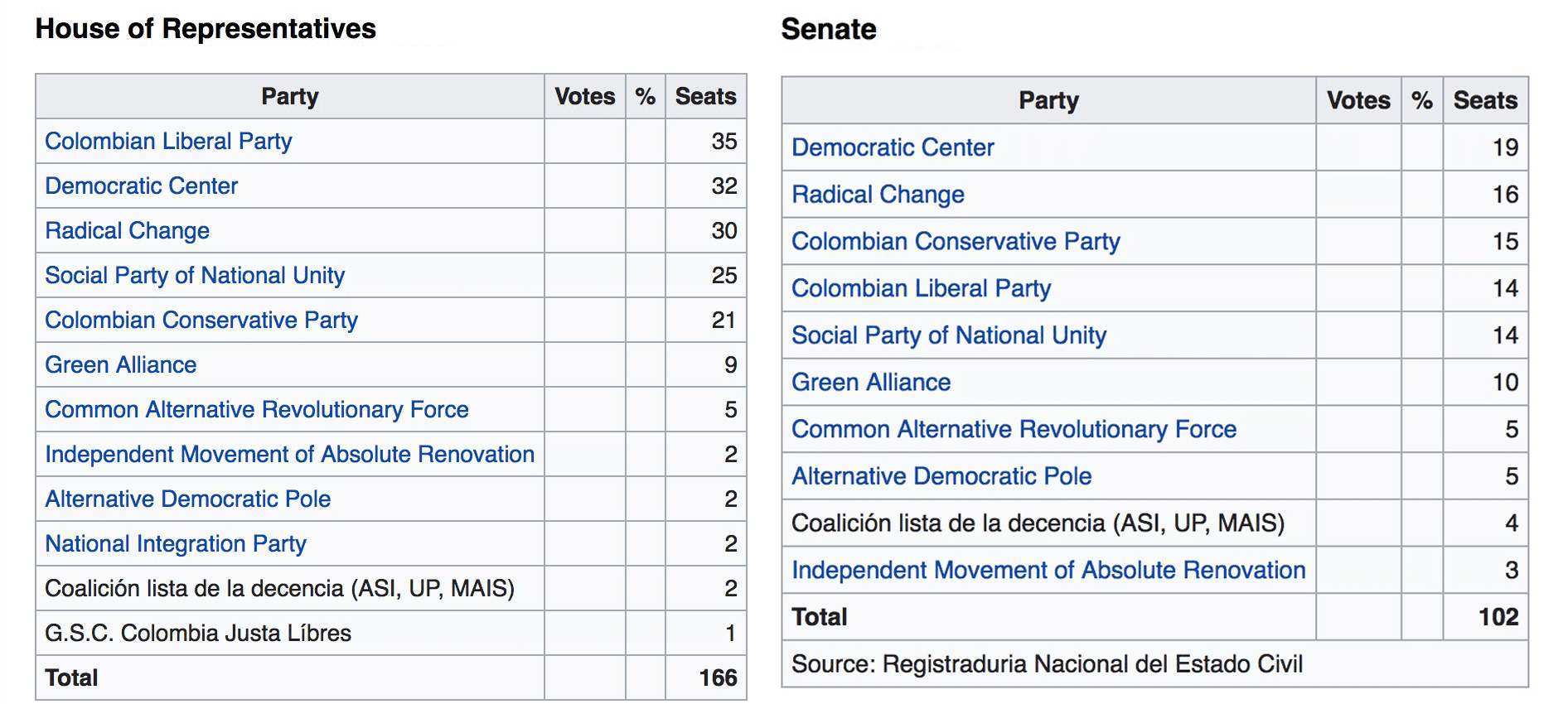

Colombia is in the midst of a presidential election season, with voting for Congress held this past Sunday and voting for President to occur in May. Sunday’s Congressional election, in which more than 5.8 million people voted, resulted in the three largest right-wing parties receiving more than 40 percent of the votes for seats in the Senate and House of Representatives. The Democratic Center, party of ex-president Álvaro Uribe, emerged as the largest, with 19 seats in the Senate, and 32 in the House of Representatives. No party achieved more than 16% of the vote, with the three largest conservative parties winning 50 of the Senate’s 102 seats.

Left-wing guerrillas, now political party Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia, or FARC, performed poorly receiving just 0.5% of the total number of votes. However by the 2016 peace deal, brokered by current President Juan Manuel Santos, FARC will receive 5 seats in each of the two chambers of parliament.

Right-wing candidate Senator Ivan Duque, who was hand-picked by former President Uribe, and leftist Gustavo Petro will lead their respective coalitions after winning primaries on Sunday. Duque, of the Democratic Center, garnered more than 3.9 million votes, over 96% of the vote. Duque beat conservatives Marta Lucia Ramírez and Alejandro Ordonez for the nomination.

Querían las fuerzas de la corrupción presentar la jornada electoral de ayer como una contundente derrota de nuestra fuerza.

NO pudieron

Ganamos como nunca en el Congreso de la República y rompímos los techos históricos con mi candidatura a pesar del fraude

GANAMOS.

— Gustavo Petro (@petrogustavo) March 12, 2018

A highly controversial figure, Gustavo Petro is a former member of the M-19 guerrilla group and a previous mayor of Colombia’s capital, Bogotá, from 2012-2015. In December 2013, he was briefly removed as mayor when the Colombian Inspector General accused him of overstepping his authority in an attempt to replace the city’s private garbage collectors. Prosecutors said he had violated the principles of the free market and endangered people’s health. Petro was banned from holding office for 15 years, before a human rights monitoring organization based out of Washington, D.C., the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (CIDH), opposed his removal as a violation of human rights. Colombia’s president Santos upheld the removal, but Petro was eventually reinstated as mayor and finished the length of his term.

Remaining candidates include Humberto de la Calle, who was a chief peace negotiator in the FARC deal, and former Gov. Sergio Fajardo, who also vowed to implement the peace deal. German Vargas Lleras, the conservative leader of the Radical Change party, a critic of the peace deal, also remains as a contender.

The surge of Venezuelan immigration, which some caution may worsen towards what may become a “Syria-sized exodus,” has become a matter of national discussion, especially in light of the coming election.

Last month, Ivan Duque marched through the streets of the city of Barranquilla, and with megaphone in hand, he assured citizens, “We will not allow Colombia to become like Venezuela.” Duque stated, “Have the full certainty that we are not going to let that happen in our country. We will never allow Colombia to go through the crises that the neighboring country is going through.” In an interview this week Duque stated, “The country does not want to run the risk of falling into the grip of populism and failed socialism in Venezuela.”

#LaNocheDuque | “El país no quiere correr el riesgo de caer en las garras del populismo y en ese socialismo fracasado de Venezuela”: @IvanDuque en entrevista con @CGurisattiNTN24 y @JoseMAcevedo | @LaNocheNTN24 @JeffersonNTN24 #AHORA pic.twitter.com/RW6YPd8GX7

— La Noche NTN24 (@LaNocheNTN24) March 14, 2018

Earlier this month, presidential candidate for the conservative party, Marta Lucia Ramírez had urged creating a quota system in Latin America for Venezuelan refugees to share the burden of the mass exodus. Ramírez said that while the situation in Venezuela is “a humanitarian tragedy,” Colombia cannot “throw itself on its shoulders” to deal with the situation alone. According to Ramírez, if Colombia assumes all the burden, “we end up sinking ourselves and them.”

Ramírez further blamed President Santos for not prioritizing Colombia, arguing that the government’s interest was to sign an agreement with FARC, at the expense of “the defense of democracy in Venezuela.” After a visit to Cúcuta earlier this month, Ramírez tweeted “Norte de Santander and the border areas of the country will have the support of our government. We are going to have a border ministry and we will take measures to resolve the employment crisis and the lack of State presence.”

Norte de Santander y las zonas de frontera del país contarán con todo el apoyo de nuestro Gobierno. Vamos a tener un ministerio de Fronteras y tomaremos medidas que resuelvan la crisis de empleo y la falta de presencia del Estado. pic.twitter.com/dXa5Vy7g5W

— Marta Lucía Ramírez (@mluciaramirez) March 6, 2018

Earlier this month Gustavo Petro had also visited Cúcuta. The city’s mayor, Cesar Rojas, a political ally of rival candidate German Vargas, initially banned Petro from visiting the city. Rojas was reminded that the ban was illegal by the Interior Minister. Upon entering the city Petro’s motorcade came under attack by civilians protesting his presence. Police launched tear gas into the crowd.

While Petro’s rise to prominence reflects the country’s growing anti-establishment wave, Duque’s popularity also reflects fears that Colombia could become another Venezuela. Petro, who is regarded by many in the business community as an arrogant latter-day Hugo Chávez, has said that “criticizing Venezuela is a way for Colombians to hide our own truths from ourselves.” For the already unstable rural areas in Colombia, the flow of Venezuelan refugees is tightening an already difficult economic situation.

And the tide of immigrants is likely to continue. Food shortages have reached critical levels. A study in February by three top Venezuelan universities found that on average Venezuelan citizens had lost 11 kg (24 lbs) of weight in 2017. Even in the country’s oil sector, which is its main export, workers are so deprived of food that they are collapsing on the job. With basic commodities like food, fuel and medical supplies increasingly unavailable, the scarcity has exacerbated criminal activity in a country which was already well known for its violent crime.

While national statistics have been suppressed, the U.S. State Department’s most recent Crime & Safety Report on Venezuela found that crime rates have reached unprecedented levels. With the government more focused on winning an election in May, and refusing to accept international aid which is conditioned on political reform, these situations are unlikely to be addressed.

Because those fleeing Venezuela are not technically “refugees,” in international law, Colombians have a relatively free hand in how they deal with the Venezuelans coming into their country. In February, President Santos terminated the border-card system, which was allowing 1.5 million Venezuelans to temporarily enter the nation to purchase food and medicine. Santos also announced the deployment of 2,000 additional border guards and a program for clearing the public parks in Cúcuta. The crackdown, however, is doing little to stem the tide, with the government estimating that the policies have only reduced migration by 30%.

Refugees and violence were not always defining features of Cúcuta; in 1821 the city was the location of a momentous historical event. The Congress of Cúcuta established Gran Colombia, a state which unified disparate liberated Spanish colonies, including modern Venezuela and Colombia, into one, and established Simón Bolívar as its first president.

The city has numerous public parks established to commemorate its history, the same parks that now house Venezuelan refugees facing an increasingly frosty reception from the locals.

LIMA CHARLIE NEWS

Lima Charlie provides global news, insight & analysis by military veterans and service members Worldwide.

For up-to-date news, please follow us on twitter at @LimaCharlieNews

In case you missed it:

![Image Venezuela's refugees add pressure to Colombia's presidential race [Lima Charlie News]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/Venezuelas-refugees-add-pressure-to-Colombias-presidential-race.png)

![Image The rise and dominance of Colombia's private military contractors [Lima Charlie News]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/Colombias-Private-Military-Contractors-Lima-Charlie-News-480x384.png)

![Image Ambitions Never Laid to Rest - An Open Society vs. The Terrorist [Lima Charlie News] (Image: Patrick Hertzog)](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/Screen-Shot-2018-12-28-at-2.37.54-PM-480x384.png)

![Image DACA Dreamers face uncertainty amid potential conflicting federal courts [Lima Charlie News][Photo: Mark Wilson]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/DACA-Dreamers-face-uncertainty-amid-potential-conflicting-federal-courts-1-480x384.jpg)

![Image Memorial Day may soon be a remembrance of democracy and those who had the courage to defend it [Lima Charlie News]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/Memorial-Day-may-soon-be-a-remembrance-of-democracy-and-those-who-had-the-courage-to-defend-it-Lima-Charlie-News-480x384.png)

![The Mind of Bolton - AUMF and the New Iran War [Lima Charlie News]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/Inside-the-mind-of-Bolton-Lima-Charlie-News-main-01-480x384.png)

![Image The rise and dominance of Colombia's private military contractors [Lima Charlie News]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/Colombias-Private-Military-Contractors-Lima-Charlie-News-150x100.png)

![Image Ambitions Never Laid to Rest - An Open Society vs. The Terrorist [Lima Charlie News] (Image: Patrick Hertzog)](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/Screen-Shot-2018-12-28-at-2.37.54-PM-150x100.png)