Turkey’s citizens recently voted to give President Erdogan expanded powers. He now has wide control over the judiciary, can simply decree law, and run two more times as president.

Marine Le Pen, currently the front-runner for the unapologetically authoritarian far right National Front Party, is poised to win the French presidency. Her platform is based on xenophobic nationalism. She readily confirms her anti-immigration, anti-Muslim, anti-globalist protectionisms with pride, promising to establish much of it by decree.

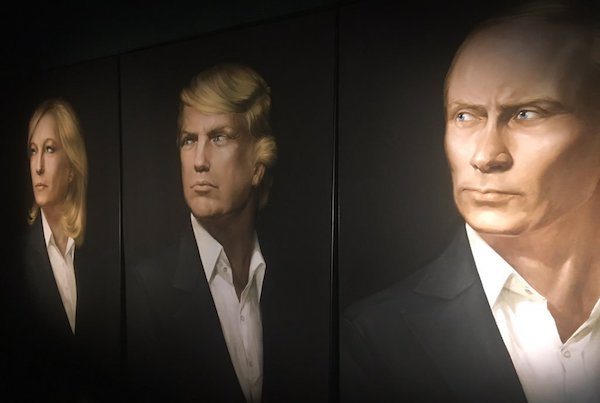

Donald Trump won the American presidency after promising to shut down media outlets that publish things he doesn’t like, shut down companies that export jobs, and asserting that whistleblowers like Snowden and Manning should be executed without due process. Much of these trends have been rooted in nationalist sentiment, like the one that gripped and compelled the United Kingdom into Brexit.

It’s a strange phenomenon. The West, after many years and many rounds of criticisms launched at the rest of the world, at dictators and authoritarian regimes of all types, from left to right, is now facing its own not-so-slow march towards authoritarianism.

Why is this happening?

Unemployment

Greece: 23.5%

Spain: 18.6%

Italy: 11.5%

Portugal: 10.5%

France: 10%

Ireland: 6.4%

Netherlands: 5.3%

UK: 4.7%

Germany: 3.9%— The Spectator Index (@spectatorindex) April 14, 2017

Many recent reports from major world outlets focus on reactions towards extended periods of economic austerity, particularly in France and Britain. France still has approximately 3 million people unemployed after decades of mass unemployment. Britain, after the austerity measures installed in the wake of the global financial collapse, has finally regained some control of its unemployment rate at the cost of a serious decline in real wages.

Poor economic conditions, such as rampant unemployment and loss of purchasing power, are prime suspects upon which to pin the sentiments of disgruntled masses. This is especially poignant when compared to how immigrants and foreigners are faring in the West’s social safety nets. The idea, as commonly presented, is that immigrants are being afforded the opportunity to enjoy the social safety nets intended for the ‘real’ native residents of those countries. That it is immoral to extend a hand to others when the natives themselves are not doing as well. This grounds nationalist movements in “France for the French,” Britons “take back control and spend our money on our priorities,” and “Make America Great Again” – jingoisms based on some notion of a romanticized past that can be recaptured if only we got rid of what’s changed.

Then there are the other just as important parts of the world.

Turkey, though not the ‘West,’ has been a staple of democratic values in the Middle East since the turn of the previous century. In Turkey the reaction seems to be against the failures of military-backed secularist leaders who have repressed Islamists, like Erdogan, for too long. Erdogan has ousted the majority of his political opponents and silenced journalists who disagree with his positions. And yet, with these clear indicators of a move towards absolute authoritarian rule, the people of Turkey have voted to give him even more power. Erdogan is seen as the answer to the infighting normally associated with coalition governments by bringing the stability of one-party dominance.

Is this move towards authoritarianism really that novel?

Alfred North Whitehead once said: “The safest general characterization of the European philosophical tradition is that it consists of a series of footnotes to Plato.” Not that every single discussion hinges on something written 2,500 years ago, or that an early 20th century mathematician is the absolute authority on Western Philosophy, but the irony is that the political critiques of democracy seem as relevant now was they were to the ancient Greeks.

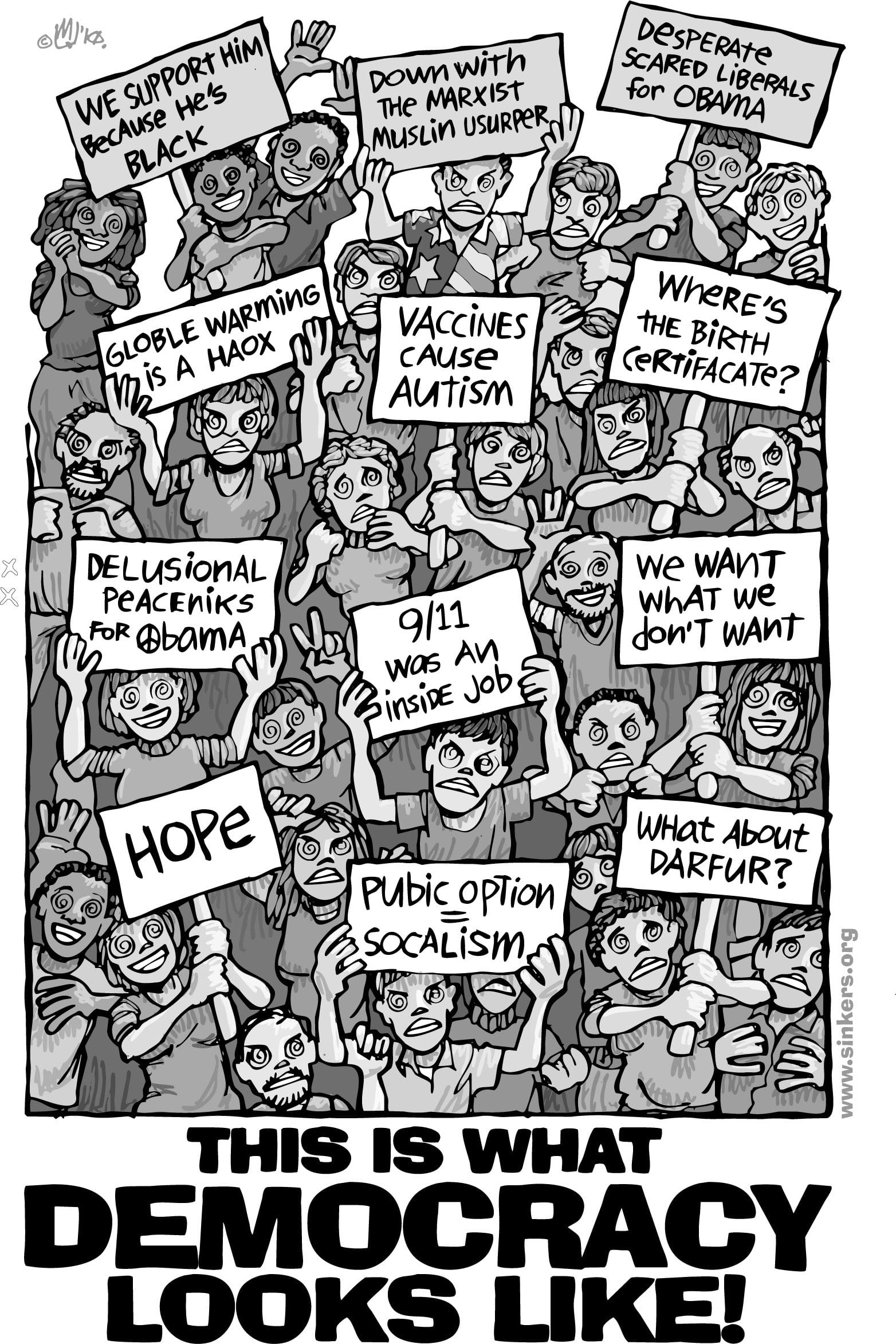

Plato’s critique of democracy is well known to any intro-to-philosophy student across the globe. His argument, simplified here, was that the simple and selfish people in democratic systems, who are always easily swayed by the professional politician, would inevitably elect the morally defunct based on populist ideas. This would drive counties into popular expansionist wars, internal conflict of class warfare, and general electorate discord. This sounds very relevant to everything experienced in the modern world.

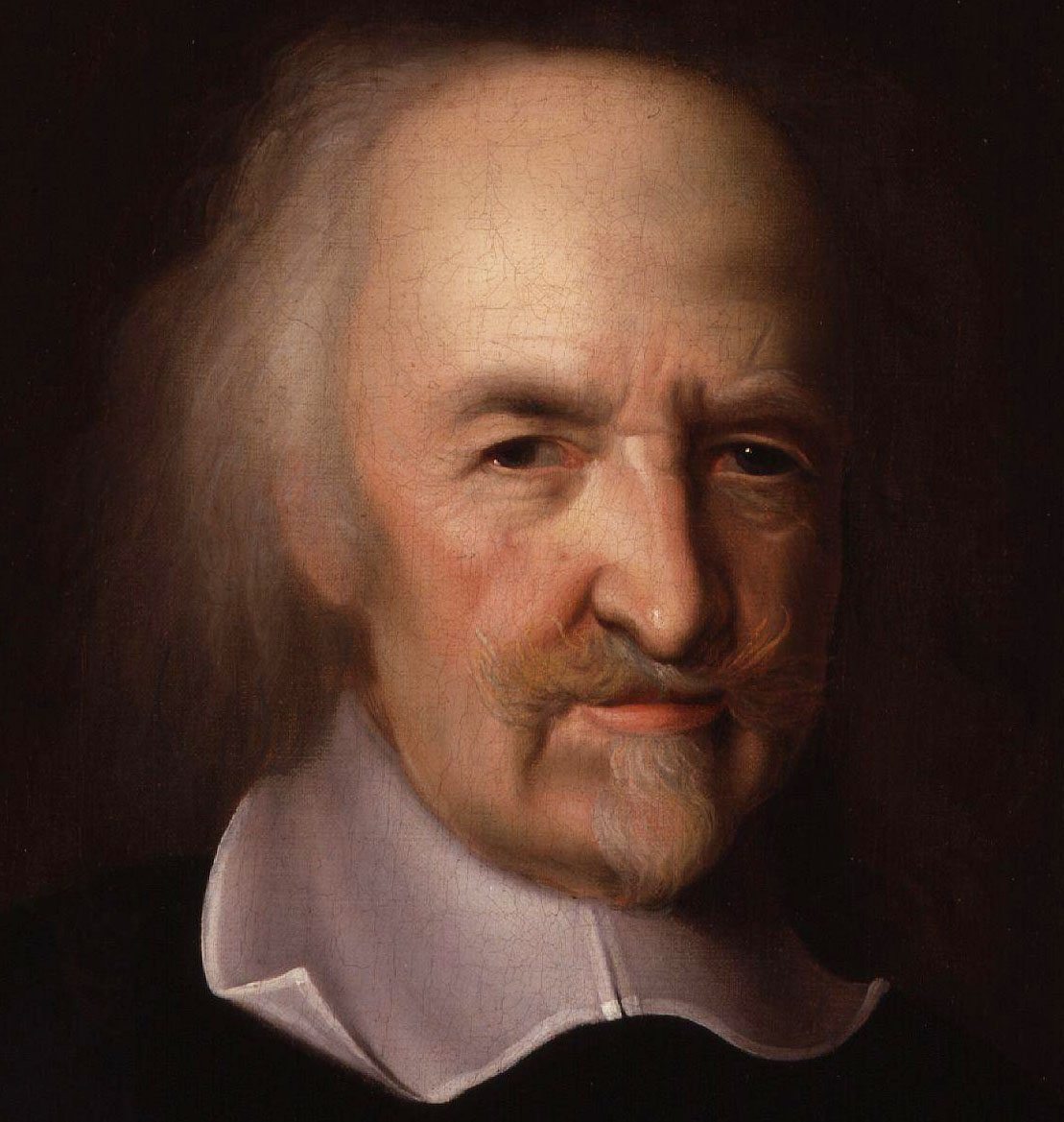

Thomas Hobbes, who wrote his political treatise at the heels of the English Civil War in 1651, a war brought on by similar ailments of class warfare, religious discord, and cavalier militarism, had a simple answer. Authoritarianism. His answer was admittedly not novel.

Kings as absolute rules had existed plenty before, but it did have the distinction of being very cohesive, complete, and most importantly simple. Hobbes argued that if people surrendered to a sovereign in every way, such as adopting the sovereign’s religion, accepting rule by simple decree, and adopting the economic system the sovereign thought best, it would bring something that no other political system had up to this point—peace.

Hobbes’ belief stemmed from the central tenet of his natural philosophy that human beings are, at their core, selfish creatures. Only by living under a ruler whose sole goal is to maintain order and peace and has the might to enforce it, could our selfish natures be tamed.

It appears that the populations of many countries have opted to agree with Hobbes and prove Plato right along the way. It seems preferable to give strong charismatic leaders who share the majority’s vision the tools to carrying out the general will, even at the cost of giving up a few rights along the way. The insecurity and uncertainty, coupled with the political discord that is inherent in democratic systems has failed. The hopes are now pinned on one figurehead who knows best for everyone to prosper, or so the propaganda machine goes.

What’s interesting about authoritarianism is that it has little concern over the ultimate goals a society sets: Bolsheviks saw the commune as its long-term goal, the Nazis a Christian capitalist homogeneity. What most concerns authoritarianism is that no one deviates too far from the norms the society has chosen and how the leader embodies them.

In this respect, no other country demonstrates this populist fascination with authoritarianism more than Russia. Vladimir Putin represents, in the eyes of his many supporters, the ideal strong leader who puts his country first. Yet, after 17 years of Putin being in power (a fact which alone should be alarming), his supporters don’t see that in many ways they’ve given up much in order to have stability. Yes, under Yeltsin everything was still a free-for-all with oligarchs reaping the rewards. However, under Putin the oligarchs still reap the rewards with the added benefit of state protection. The country does not have a free press, elections are mummer shows, and people have little in social protection. In effect, Russia is an authoritarian capitalist state and despite that, Putin as it’s autocrat enjoys an 86% approval rate.

In thinking about the dangers of authoritarianism I am always reminded of the meme, “’I never thought leopards would eat MY face,’ sobs woman who voted for the Leopards Eating People’s Faces Party.” This tweet by Adrian Bott gets to the heart of the matter. It’s never a question of if, but when the politician who now enjoys legislating and enforcement without reproach and with impunity will turn on those who put them in power.

‘I never thought leopards would eat MY face,’ sobs woman who voted for the Leopards Eating People’s Faces Party.

— Adrian Bott (@Cavalorn) October 16, 2015

The examples from history of this happening are plenty and wouldn’t really add much to a discussion of authoritarianism. Pointing out how Putin, Trump, and Erdogan have rolled back on civil liberties, civil protections, or their cavalier militarism with disregard to their campaign promises also adds little to the conversation. Their failings are being well documented by many who are watchdogs for their societies or simply just don’t like their political wing. Instead, it’s important to consider the ramifications of these marches towards nationalist and autocratic regimes and what it could potentially mean to both the established and developing world.

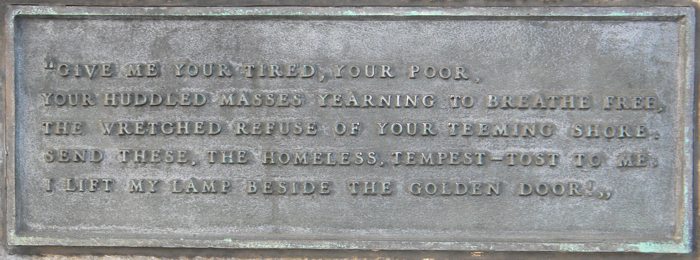

First, it should be noted that the U.S. is not an authoritarian regime. In spite of the leftist opposition to the many Trump promises and attempts to reverse Obama’s policies, Trump has not yet made the institutional changes to cement lasting power for himself or for a successor. The biggest reason to bring Trump into this discussion is the recent predilection of the American electorate, who in so much of its history has shown distaste for totalitarianism, since the end of WWII distaste for isolationism, and on its own monuments called for the world’s poor and neglected, to do an about face and prefer a candidate who promised by decree to return America to a former imagined glory of protectionism.

Next, it should be acknowledged that in the race towards isolationism and protectionism, the only country in history to fully accomplish it was 15th century Ming dynasty China. While the rest of the world lived in comparative squalor, China, the wealthiest country in the world at the time, effectively closed itself off to the ‘barbarians.’ Travel distances and times back then allowed for such a thing to happen without any real dispute. It is also this same sudden isolationism that is credited with the end of Chinese maritime supremacy. Some credit it with its eventual collapse.

However, in our current globalized world, hardly any country can avoid the effects of markets and political unrest in another part of the world, no matter how remote. Isolationism and protectionism are by nature anti-trade and anti-immigration. This hurts world and domestic markets, is a myopic solution to social unrest by scapegoating, and ultimately damages more than it helps, as evidenced by China’s history. Capitalists should be keen to remember that the father of capitalism, Adam Smith, wrote his treatise as a critique against the protectionist measures of mercantilists and physiocrats of his day. It is he in fact who uses China’s isolationist position as an example of what not to do if you want to be an economic superpower.

Professor of political science at Fordham University, Asha Castleberry, states that these moves and trends are as much reactions against globalization and interventionism as they are protectionist. These bombastic leaders promise looking inward for fixing social problems, while antagonizing international organizations, such as NATO or the UN, and not supporting more foreign wars and their associated costs. However, every person mentioned so far has proven the claim of isolationism empty. With the exception of Le Pen, all of them have been involved in a foreign conflict. At some point, Trump will have to face his supporters who voted him into office on the promise of no more money spent on foreign intervention.

So in one sense, the promises of protectionism, such as ‘place us first,’ and ‘make us great again,’ are pipe dreams. In an interconnected world, even the “hardcore” find reasons to interact with the rest of the planet.

Trump now says he supports NATO, but not a strong Europe. And in France, as today's tweet makes clear, he's rooting for Le Pen. https://t.co/jJoKdmM5a7

— ian bremmer (@ianbremmer) April 21, 2017

It’s also interesting that many of these reactions came at the heels of what many perceived as the failures of globalization. The reactions against globalization have become polarizing and the narrative very protectionist and nationalistic. For example, globalization brought immigrants to nativists’ homes, to use up their resources, which weren’t enough for the said natives. Globalization has involved the countries in various wars of which both the monetary and human costs are high. Globalization has allowed foreign powers to dictate how local people must conduct their daily business by threatening them with plentiful inexpensive goods from somewhere else. It seems that the attitude is, ‘sure globalization allowed for the Internet to be exported from the United States to the world and allowed the United States to enjoy the world’s resources in infinitely new ways, as one massive example, but what has globalization done for me lately?’ The international cooperation that brought forth the information superhighway revolution is now passé and outdated, at least politically.

This is an important point, one that Prof. Castleberry highlights; in spite of the internet allowing information to be readily accessible globally, the electorate, like the one Plato disparaged, is not informed, which allows the self-styled to get away with a great deal. In looking at Trump’s 180-degree turn from vehement opposition to NATO, he will get away with changing his position simply because his supporters weren’t informed on the functions of NATO, and are much less interested now that their choice is in charge. He ‘will take care of it,’ whatever that means.

An uninformed electorate is indistinguishable from an ill-informed one. The argument that the people are just not as savvy as they think they are and are being duped into voting for leaders, which may promise the contrary, but don’t actually have their best interests in mind, has a hard time gaining traction because ultimately it hinges on calling people stupid. No one wants to be called stupid, even when their actions clearly show that they are voting against their own interests.

Then there are arguments from experts such as, John Sjoholm, Lima Charlie News’ MENA Bureau Chief, that parts of the world just aren’t ready for democracy. Look at the unrest in Egypt, Syria, Libya, Iraq, Afghanistan, and alike. The west and the world was better off supporting the autocrats that once stood than the ensuing chaos of the power vacuums left behind. Sjoholm makes the argument that these countries don’t have the institutions that allow for democracies to take root. He points at Jordan as an example of one country that is slowly introducing democracy with great success as slowly the people become accustomed to the new political climate.

In essence, this last claim seems to be a nuanced argument of the ignorant electorate. The people of some countries just don’t have the democratic habits to maintain a running healthy democracy.

Yet, we aren’t talking about countries that don’t have histories of democracy, we are talking about the United States, France, Turkey, and to some extent, the United Kingdom. These are mature democratic regimes with long histories of global involvement, secularism, and anti-authoritarianism that are experiencing a moment of backsliding. Christian conservative values, after years of being relegated to, at best, ancillary roles are now prime public motives for social reform. In the case of Turkey, it’s Islam, but the net effect is the same.

Even the revolutions dubbed “Arab Spring” have been different from previous revolutions. Since the American Revolution (or maybe the British) onward, the majority of the world’s revolutions have been about trying to get rid of the tyranny of the majority and/or elites, while establishing governments that were representative of the entire population. At least that is the history for the West. Most democratic regimes across the Western world have moved to some kind of proportional representation in order to stabilize their democracies. The rest of the world has fought often times bloody battles to achieve some type of Western democratic order. Yet, since the Arab Spring, revolutions have been centered around establishing theocratic and ultimately autocratic regimes. This is a stark change.

In all, it seems that the romance with democratic systems is over. The world is disillusioned with the constant infighting and bickering of democracies. The promises of non-interventionism have proven to be a farce. Instead, the world’s populations seem to be asking for someone, anyone, to take charge and make their life simple by only having to worry about themselves. More embarrassingly, after 2,500 years we are still arguing about the same things that crippled ancient Greece. We are still trying to deny others the rights we would want for ourselves in the name of security and retaliate fiercely when challenged on our hypocrisy.

After thousands of years of civilization, we still have a revenge cult. It seems authoritarianism is our poison of choice in extracting revenge.

Jose Robledo, Political Correspondent, Lima Charlie News

Jose Robledo is a former Army Staff Sergeant still Army Infantry Officer. After completing two combat tours, to Afghanistan and Iraq, he studied Political Economy at Columbia University, where he successfully led the student initiative to bring back ROTC to the campus.

Lima Charlie provides global news, insight & analysis by military veterans and service members Worldwide.

For up-to-date news, please follow us on twitter at @LimaCharlieNews

![Blossoming Russo-Turkish alliance leaves U.S., NATO behind [Lima Charlie News]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/Russia-Turkey-alliance-leaves-U.S.-NATO-behind-480x384.png)