Being political is an integral part of being Iranian. Our lives are defined by politics.

– Shirin Neshat (Iranian artist)

On May 19th the Iranian people go to the polls to decide whether the country will continue its path towards being a valued member of the international community, or reverse towards a more theocratic, and militaristic, regime. The upcoming Presidential election will not just determine the regional superpower’s place in the region, but it will make a lasting impact on the security landscape of the Gulf, and the regional policies of the last remaining superpower.

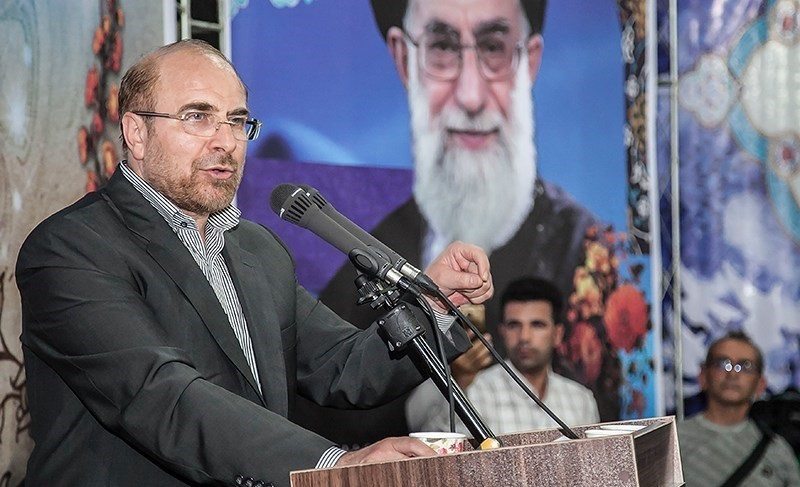

This could very well be the most important election in the history of the Islamic Republic to date. While the Presidential ballot consists of six candidates, only three are actual contenders. The other three are merely there to fill the void, running in name only, with no hope of being elected. All six candidates were approved to be on the ballot on April 20th by the Guardian Council of the Constitution, a semi-religious council under the indirect leadership of the Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei, which decides who is eligible to run for public office. The main candidates consist of the incumbent President, Hojatoleslam Hassan Rouhani, Hojatoleslam Ebrahim Raisi, and Mohammad Ghalibaf. These three candidates represent the dividing lines of the Iranian political spectrum, widely different political configurations, and significantly different futures for Iran.

The Iranian political spectrum can be divided into three main categories, that are then configured and anchored with each other. The Technocrat (Academics and Bureaucrats), the Clergy, and the IRGC (“Military”), are the prevailing faiths to which each candidate has to align himself and configure a power bloc out of. These configurations of the political alignments are crucial in understanding what options candidates truly represent.

Raisi and Ghalibaf both represent authoritarian configurations. The incumbent candidate, Rouhani, represents a Technocrat-Clergy configuration, which makes him a relative moderate and Tehran oriented leader. This makes him someone the West can do business with. It was this configuration that enabled Rouhani to sign the so called “Iran Nuclear Deal” (Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA)) with the US and the international community. Raisi on the other hand represents a Clergy-IRGC configuration. This configuration means that the Clergy, under the leadership of Iran’s Supreme Leader Ayatollah Khamenei, would have significantly more influence as well as represent a more nationalistic and aggressive regional stratagem. Ghalibaf in turn represents an IRGC-Clergy configuration, equaling an increase of military authoritarian rule with the Clergy backing it. Under the rule of either Raisi or Ghalibaf we would see an immediate reversal of any progressive movements in the country, an increase in offensive tactics throughout the region, and a possible dismantling of the Iran Nuclear Deal.

Raisi and Ghalibaf would not only attempt to dismantle the Iran Nuclear Deal to appease their IRGC masters, but also to commit to the postmodern tradition of grandstanding against the US. More importantly, they would do so to strip Rouhani of his legacy.

Many poets in Iran have learned to speak almost a secret language, where political issues are talked about in allegorical ways.

– Reza Aslan (Author, Iranian-American)

Recent Political Developments

Western analysts have largely seen Iran’s political spectrum as a near-binary static affair featuring hardliners and relative moderates. However, in the past two decades Iran has suffered immense political infighting, which has resulted in a radical political paradigm shift. The shift has reinforced Technocratic power bloc influences at the expense of the Clergy, and to a lesser extent the IRGC. While acceptance from the Clergy remains essential to create a government, its influence in the resulting government has waned. In the 2017 election the Clergy bloc seeks to remedy this, and it intends to do so by installing its own candidate, Raisi. Failing that, Ghalibaf will do nearly as well as far as the Clergy is concerned.

These developments have rendered many traditional Western observations of Iranian politics nearly null and void. The chasm became conspicuously clear with the election of Mahmoud Ahmadinejad in 2005. Ahmadinejad represented an IRGC-Technocrat configuration. Under the Ahmadinejad presidency, the civilian executive branch sought to strengthen its powers at the expense of the Clergy bloc influence, making it less dependent. The Clergy struck back by undermining the IRGC side of Ahmadinejad’s support, leaving him entrenched with the Technocrat bloc. By this time, he had already laid his IRGC-hardline course however, becoming unable to escape its vortex with no real benefit to himself or the Technocratic bloc. As a result of this, Ahmadinejad arguably failed in his endeavor to strengthen the executive power as an independent power bloc.

Ahmadinejad’s efforts were piled onto the efforts of the previous President, Mohammad Khatami (1997-2005), who used a Technocrat-Clergy configuration to give the Technocrat bloc the upper hand. Khatami’s presidency stood in stark contrast with his four Presidential predecessors, especially Hashemi Rafsanjani (1989-1997) who had been a keen supporter of the Clergy bloc during his Presidency, using a Clergy-Technocrat political configuration.

It was during Khatami’s Presidency that the lasting cracks in the Iranian political foundation truly began showing, and Khatami’s successor, Ahmadinejad, laid significant weight unto the fractured parts of the spectrum – causing these cracks to expand – for his own benefit. President Ahmadinejad ran out of time in the Sa’dabad Complex (A 300 hectare complex built for Persian Monarchs long since gone, in Tehran, now serving as the official residence of the Iranian President) before he could fully take advantage of these cracks.

President Rouhani has been able to use these cracks, and their resulting shifts in power blocs, to reintroduce Iran to some extent to the international community. Rouhani is no Khatami, who ran on a liberal reform platform which advocated freedom of expression, and immensely increasing diplomatic relations. Nevertheless, he represents the return of dialog, and the faint possibility for dormant long-term progressive reformist movements to safely resume operation in the country.

“Iran’s goal is not to become another North Korea – a nuclear weapons possessor but a pariah in the international community – but rather Brazil or Japan, a technological powerhouse with the capacity to develop nuclear weapons if the political winds were to shift, while remaining a nonnuclear weapons state.“

– Mohamed ElBaradei (Diplomat, Egyptian)

Marg bar Amrika!

As far as most Westerners are concerned, the Islamic revolution in Iran began with a bang on November 4th, 1979, when a group of religious students seized the United States Embassy. During the siege the students held 52 individuals inside the embassy compound hostage. The revolution had already been brewing for several years. With hindsight, it is now clear that the dam was about to burst. The revolution’s leadership had used a mixture of religion and nationalism to stir the pot. Iran’s role as an Ancient Civilization with a proud empire was invoked to stir up nationalist sentiment. Iran’s history was contrasted with its present as a colonialist controlled satellite state. The US and the UK were chiefly pointed out as the puppet masters of the Shah and his regime. As such, the battle cry of the revolution was often a mixture of Allah Akbar, meaning “God is Great”, and Marg bar Amrika which means “Death to America.”

Earlier that year, in January of 1979, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, the head of the Pahlavi royal family, and leader of the Iranian nation fled to the United States. The de facto dethroning of Shah Pahlavi meant that the Islamic revolution was underway. The revolution meant that Iran was moving away from a seemingly pro-Western and pro-American foreign policy to one that could be described as Iran first. This new policy replaced the progressive and modernizing capitalist economy with a populist and Islamic economy. The westernized culture and rules of society were replaced with ones that represented a more traditional Islamic attitude.

“My family fled Iran in October 1978 as a result of the coming revolution when I was two years old. In the early days, my entire family lived together in a very crowded house, where I shared a room with my sister, cousin, and grandmother, and we would all listen to my grandmother tell stories before bedtime.“

– Pardis Sabeti (Scientist, Iranian-American)

In the revolution’s initial days, and in the immediate aftermath, the religious leadership had complete control over the nation. By February 1979, the revolution’s religious leader Ayatollah Khomeini appointed the long-time pro-democracy activist Mehdi Bazargan as the first Prime Minister of the new nation. Bazargan would resign a few months later in protest over the United States Embassy siege, and Ayatollah Khomeini’s refusal to condemn the students’ act. Following Bazargan’s act of defiance, the post was left vacant and the power vacuum was filled by an Islamic council, until 1981 when Mohammad-Ali Rajai was selected for the position by the now Supreme Leader Khomeini, a post that was created for, and by, Khomeini in December 1979. Rajai left the position of Prime Minister in favor of the Presidency-position a few months later. A string of short term Prime Ministers followed, with the position becoming increasingly weakened and meaningless. In 1989 the position was abolished by order of the new Supreme Leader, Ali Khamenei. The post had fundamentally already been replaced in 1981 by the role of publicly elected President.

The office of President is becoming increasingly more powerful and is the highest electable office in Iran. Nevertheless, the Supreme Leader remains the official head of state. In recent years, the current Supreme Leader, Khamenei, has been not been overtly involved in matters that are related to the President’s office. This seems to be a strategy to strengthen the perception of the civilian leadership. However, the Supreme Leader appoints the majority of the members of the Guardian Council, which evaluates candidates for the Presidency. Khamenei himself served as President between 1981 to 1989, before he ascended to the position of Supreme Leader after the death of Khomeini.

Because Iranians have had to fight so long and painfully for political freedom, they have a deep appreciation for its value – perhaps deeper than many in the West who take their electoral rights for granted.

– Stephen Kinzer (Author, American)

After Khamenei, the Presidency quickly evolved to represent the various non-Clergy affiliated factions in society, predominantly the IRGC and the Technocrats. Khamenei’s successor to the role of President, Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani, was primarily aligned with the Clergy-IRGC configuration. Rafsanjani played a significant role in the Iran-Iraq war of 1980 to 1988, and was a proponent of the free-speech movement in Iran. In 1997 Mohammad Khatami (Technocrat-Clergy) was elected on a liberal reformist platform, only to be followed by the hardline candidate Mahmoud Ahmadinejad (IRGC-Clergy) in 2005. In 2013 current incumbent, and now candidate, President Hassan Rouhani (Technocrat-Clergy) became President.

To some extent, both Khatami and Rouhani have come to represent a deeply seated, and culturally significant, throwback to the Persian empire and its partiality towards technocrats and academics. With Iran being a country of nuances, it often becomes so complex that even Iranians themselves find difficulty understanding their country and countrymen. These nuances are often infinitesimal shades of the same color, but represent enormous changes and movements underneath the upper layers of society. Outside observers often find these movements impossible to detect, unless one knows where, when and how, to look.

The seemingly despairing need in Iranian society to modernize, and westernize, is not necessarily held back by the pious. Often times society finds that the two are uniquely intertwined. Iranian culture encourages discourse to the point where it often seems like nothing can be agreed on between individuals in the short term. More academically minded Iranians tend to say, in jest, that their peers will seek to understand the other side in a discussion to the point where nothing can ever be decided. This variation of very typical Persian discussions is part of why Persia has, historically, been inclined towards seeking singular individuals to represent a unified leadership. Since the Islamic Revolution, the nation has thus been torn between unifying behind an Ayatollah, or a publicly elected President.

As Iran continues to evolve, the battle cry of the revolution, “Marg bar Amrika,” or “Death to America”, is still heard daily on the streets today. Meanwhile, its meaning has evolved. In 2015, Khamenei defined the slogan as meaning death to arrogance and American regional policies, rather than a threat against the American nation and its people.

The Concerting Voter

The different configurations of politics do not just represent different perspectives on political, social, cultural, and foreign policy levels. The configurations also represent widely different ideas on how to approach the nation’s finances, and economic development. This is the topic that matters most to the voters of this isolated regional power, and where the incumbent, President Rouhani, finds himself in a direly exposed position. As a known entity, with a recent track record, it is easy for the relative unknown challengers to point towards Rouhani’s failures to safeguard Iran’s economic development. The nation has for many years suffered high unemployment rates, before and during Rouhani. The official unemployment percentage in March 2016 was 11%, and by March 2017 it reportedly stood at 12.4% across the board.

Rouhani has, during his campaign, also focused on attempting to gain the female vote, especially in the metropolitan cities of Iran, but this is also where female unemployment stands at its worst. Iranian females between the ages of 15 and 29 have a 26% unemployment rate. Rouhani’s supporters have combatted these concerns by pointing out that the majority of Iranian GDP comes from the largely male dominated oil related industries. These industries represent nearly 90% of the total Iranian GDP growth value. At the present the all inclusive GDP growth of the country stands at a solid 7.4%, but that is with the oil sector included. If removed, the figure drops far below one percent. The most prevalent industry after the oil industry? Export and production of handmade rugs.

“For me, Iran was paradise, and I believe it’s a paradise still, but only if you don’t have political problems. If you have a political problem, paradise turns into hell.”

– Golshifteh Farahani (Actress, Iranian)

Another major problem for the administration, and its reelection possibilities, is the public perception that Rouhani and his administration primarily serve the people in the nation’s capital, Tehran, and the upper 4% of society. Rural Iranians tend to perceive people in Tehran as primarily having relatively high paying academic or administrative jobs, and as being far removed from the realities of the rural countryside. An example given is the oft-critiqued JCPOA, which did lead to some economic improvements, but primarily these improvements only concern the larger metropolitan areas.

The rural countryside, and the industrialized sector, is where both the opposition candidates find the majority of their supporters. Ghalibaf has on multiple occasions pledged to create millions of new industry jobs, and to serve “the other 96%” of the people. One of the minor Presidential contenders, Mostafa Mirsalim, has made it a point to often be seen wearing a dirty blue coverall, and a hard hat, to enhance the perception of him representing the hard working Iranian industry worker. The premier contender, Raisi, has in turn made a point of talking about the perceived corruption of the bureaucratic sector (i.e. a major part of Rouhani’s technocratic power bloc) in Tehran. These issues are not trifling matters. 40% of the population lives at or below the poverty line, and this will likely increase by millions of people. Rouhani in turn argues that the dip in job creation is a temporary element outside of his immediate control, and that with foreign investments on the rise, and inflation being down to single digits for the first time in a generation, job creation will soon increase again. As is the norm during public elections all candidates are promising to commit to job creation, if elected.

What will happen?

Rouhani’s diplomacy with the West is likely a good thing in the long term, but in the short term it has failed to bring promised financial benefits for the vast majority of Iranians. This has greatly damaged the optimism of voters, something that will weaken Rouhani at the polls. In past elections, the best chance for moderates and reformers to win has always laid with the Iranian voters proclivity in failing to unify behind a single candidate. In this election, the slightest error on Rouhani’s side, or a flippant (but calculated) remark from the Ayatollah, might take this tendency to come to a head.

The Supreme Leader, and the IRGC, have cause to concern themselves greatly with this election. Beyond the immediate changes the election will cause in the dynamics of Iranian society, this election can affect the course of the country in a different way. The Clergy high leadership, and the pool from which the next Supreme Leader can be selected, is growing increasingly advanced in age. The President does not have a direct say in the selection of the next Supreme Leader, but the next President might have an immense impact on the shaping of the society from which the next Ayatollah is selected.

“It’s very difficult to talk about religion in Iran because religion has gotten so mixed up with politics.“

–Asghar Farhadi (Film Director, Iranian)

Khamenei, the present Supreme Leader, is 77 years old now, and is reportedly not in good health. It is deemed unlikely that Khamenei will be able to stay in his position for long. With Rouhani remaining the likeliest candidate to win, it is not inconceivable that the Supreme Leader and his Clergy advisers will decide that a more direct measure must be taken to facilitate a desirable outcome. A desirable change in leadership. If this occurs, the Supreme Leader will turn to the IRGC, who will favor its own candidate to be victorious. This would mean that Ghalibaf would win, probably with just barely enough margin to make it interesting. The Supreme Leader has already injected his wishes in the election when he, through his Guardian Council proxies, ‘disqualified’ former President Ahmadinejad’s request to stand in the election.

No doubt the Ayatollahs have a long memory, and an even longer perspective on what needs to be done to safeguard the position of the Clergy in Iranian society.

John Sjoholm, Lima Charlie News

[Edited by May Hamza][article submitted May 12, 2017]

[Main image: Abedin Taherkenareh/EPA]

John Sjoholm is Lima Charlie’s Middle East Bureau Chief, Managing Editor, and founder of the consulting firm Erudite Group. A seasoned expert on Middle East and North Africa matters, he has a background in security contracting and has served as a geopolitical advisor to regional leaders. He was educated in religion and languages in Sana’a, Yemen, and Cairo, Egypt, and has lived in the region since 2005, contributing to numerous Western-supported stabilisation projects. He currently resides in Jordan. Follow John on Twitter @JohnSjoholmLC

Lima Charlie World provides global news, featuring insight & analysis by military veterans, intelligence professionals and foreign policy experts Worldwide.

For up-to-date news, please follow us on twitter at @LimaCharlieNews

![Image Iran's election - what does it mean? [Lima Charlie News]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/Iran-election-main.jpg)

![Iranian crackdown on MEK shows the activist group has popular support [Lima Charlie News]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/Iran-MEK-Lima-Charlie-001-480x384.png)

![Image The Fears of Iran and its Forgotten Kurds [Lima Charlie News]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/Fears-of-Iran-and-its-forgotten-Kurds-Lima-Charlie-News-480x384.jpg)

![Image Iran vs. the European Union - A Murderously Difficult Balancing Act [Lima Charlie News]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/Iran-vs.-the-European-Union-Lima-Charlie-News-480x384.png)

![Iranian crackdown on MEK shows the activist group has popular support [Lima Charlie News]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/Iran-MEK-Lima-Charlie-001-150x100.png)

![Image The Fears of Iran and its Forgotten Kurds [Lima Charlie News]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/Fears-of-Iran-and-its-forgotten-Kurds-Lima-Charlie-News-150x100.jpg)