Part 3 of the “American Foreign Policy Review” series “Saudi Arabia, al Qaeda and the Salafist Dilemma” takes a a look at our regional allies and foes. Continued from Part 1 and Part 2.

Our premier ally in the Middle East, the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, has long participated in a global war against Western interests. From a covert trade war against American oil interests, to the support of jihadist terror groups, to edging the world towards all out war with Iran, for over thirty years Saudi Arabia has been the puppet master of war against America.

If you know the enemy and know yourself, you need not fear the result of a hundred battles. If you know yourself but not the enemy, for every victory gained you will also suffer a defeat. If you know neither the enemy nor yourself, you will succumb in every battle.

– Sun Tzu, The Art of War

Enter: Tinker, Diplomat, Soldier, Journalist

“The Israelis and Saudis are shaping and framing the dialog erroneously. It’s not practical. We keep backing the losers, just because they shape the dialog. I don’t even see why we keep this black and white approach to the Middle East anyway,” said my friend “The Diplomat”.

My friend will never be any more of a diplomat than I am a writer. Yet, his concisely expressed viewpoint is one often uttered today. What would have been considered defeatist poppycock a little over a decade ago, is now taking root as truth around the inner sanctums of power in London and Washington.

Together The Diplomat and I had fought on the proverbial frontlines of the not so secretive war against Iran and its proxies in the Middle East; an ongoing war that rages throughout the region, and beyond. Its epicenters have remained constant; Lebanon, Syria, Iraq, Qatar, Bahrain and Yemen. Occasionally, a flare up within Saudi Arabia’s Shi’a community allows Iran to play to the galleries, much as Arab leaders across the region use the Palestinian-Israeli situation to further individual causes.

Together The Diplomat and I had tinkered in tribal politics in Yemen’s no man’s land. We diplomatically broke down doors in Iraq. We soldiered up hills in the Bekaa Valley in Lebanon. Occasionally we managed to write up some quick and dirty reports about our adventures.

Throughout our time on these frontlines of ill defined wars and ill defined allies, our enemies primarily came in three distinct shapes: the generic Salafist Jihadist; the Iranian agent and proxy; the Washington D.C. red tape pedantocrat and technocrat. These were the primary opponents to our world, a world seemingly grayer, utterly devoid of the shining light of patriotism and belief frameworks. This was a world more inclined towards realpolitik and weltschmerz (a word that literally translates to “world pain”).

Along with the dirt on our boots, nearly two decades of making the world “a safer place” gave us a unique perspective on America’s approach to the Middle East. Through this prism we often came to the conclusion that America’s approach was a flawed one.

Before The Diplomat’s current lot in life, he had been a dirty peacetime US Marine with barely a thought in his head. For awhile, before he had developed a taste for sushi and learned how to wear fine suits, he had worked as one of my former employer’s intelligence gatherers in the Middle East. This consisted of constant travel between hubs of business, places of ill repute, and 1-star hotels. Our former employer was not one to look kindly upon expense reports.

After the shop closed up, my friend ended up working for a think tank in D.C. where he helped propagate a slightly abrasive form of neo-colonial, pro-Israeli approach to the outside world. Then Donald Trump was elected president and my friend found himself, yet again, on a short list of people tasked with traversing the world. This time with a fancier set of papers.

He came to play the role of court jester, also known as diplomat. One assumes he was better paid this time around, and had less people intent on beating him senseless. He had just recently returned from Saudi Arabia, often undertaking such trips.

Before The Diplomat’s current lot in life, he had been a dirty peacetime US Marine with barely a thought in his head.

I traveled to Oslo, the capital of Norway, to meet The Diplomat. We often meet when we are both in the same hemisphere. Sometimes we even manage to remain sober during said meetings, by all appearances. It used to be that we constantly haunted bars across Dubai, and some might conclude that we drive each other to drink. Even if true, it’s chiefly his fault, him being the odd one.

This time, as our discussion deepened and the bottles of whiskey lightened, I confessed that I had been suffering recently from a terrible case of writer’s block. Always one to be supportive, my friend offered, “God is being kind. Your writing is deplorable.” Pause, sip. I ignored the ribbing as one is prone to do when told vexing truths.

“You could always write something light hearted, y’know … like speeches for the President … Or a review of American Foreign Policy,” he said under his breath, the clinking of ice against glass punctuating his sentence.

Changing Saudi Arabia for the better means helping the region and changing the world. So this is what we are trying to do here. And we hope we get support from everyone.

-Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman

A New Dawn Rises Over The Kingdom

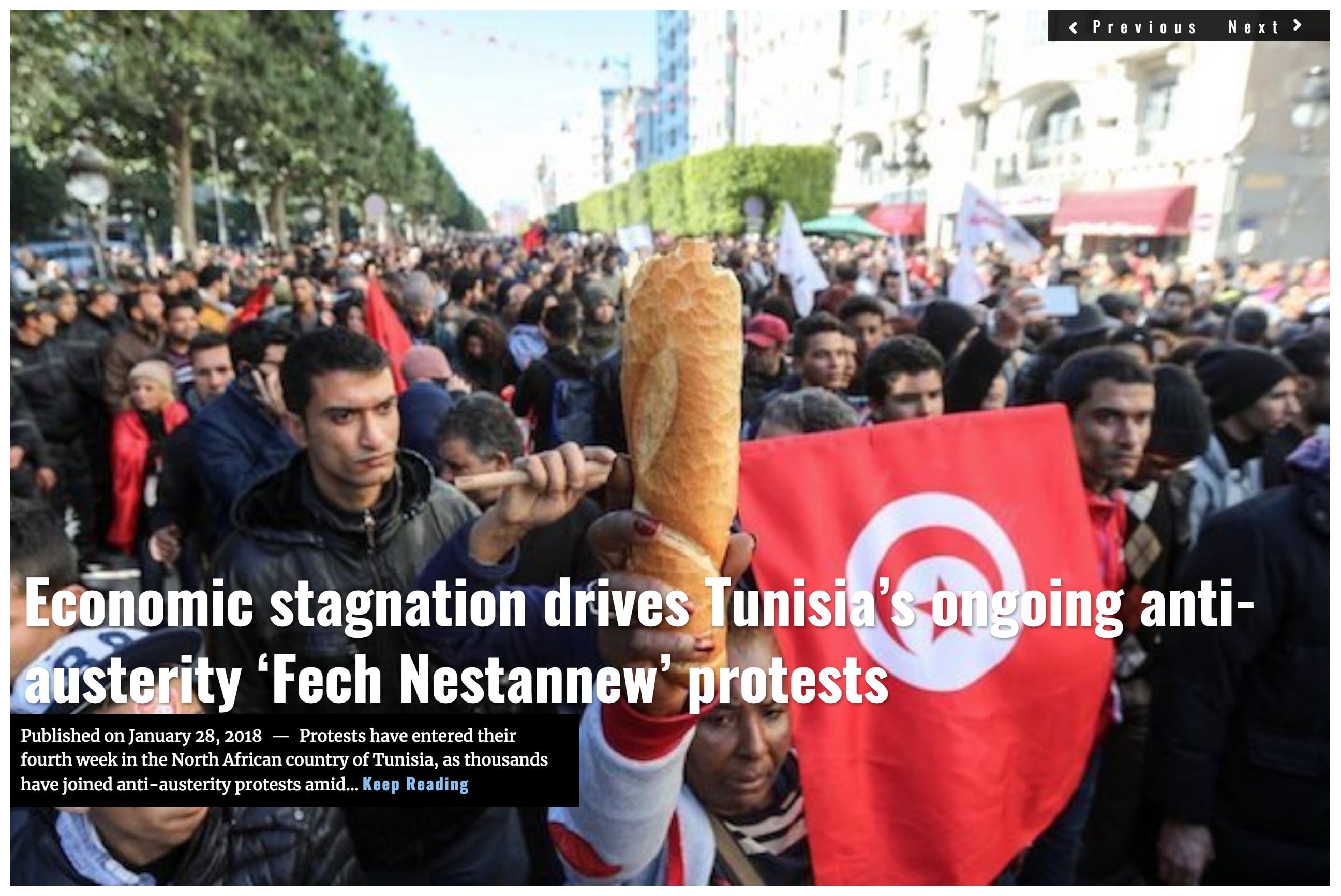

The past 16 years have been turbulent ones for the Middle East. Saudi Arabia has felt the winds of change more so than most. Its domestic economy is in dire need of reform, foreign investments are in flux, and its engagement in various conflicts throughout the region is proving to be extremely costly. Never before has the country been as dependent upon the good grace of outsiders as it is today.

As a result, Saudi Arabia has been on a charm offensive with Western leaders, while introducing some relatively progressive reforms. These reforms have come at the expense of upsetting the fundamentalist scholars in the country.

In September, 2017 the Saudi government arrested the religious scholars Salman al Awdah, Wad al-Qarni, Ali al-Omary, Salman al-Ouda, and Khalid al-Ouda, along with untold numbers of writers, activists and several officials from the justice ministry. Others were reportedly strong-armed into silence to avoid arrest. It was not until these developments that the announcement of allowing women to drive was possible. This despite the fact that the policy shift had been vocally discussed ad nauseum for years. As the decree to allow women to drive will not actually be enacted until June 2018, some doubt still remains. But there is no doubt that Saudi Arabia’s stock will still see a favorable gain in the meantime.

In a late October 2017 interview with The Guardian Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman vowed to bring the ultra-conservative state of Saudi Arabia to “moderate Islam.” With this statement the Prince gained favor with humanitarian observers and activists across the world.

The “moderate Islam” statement came amid the announcement that at long last, Saudi women would be allowed to drive on public roads and attend public gatherings. The Prince also announced that Saudi Arabia would invest over $500 billion in developing an independent economic zone. The Prince made clear his primary goal: to turn the Kingdom away from a near total dependence on oil, and create the fundamentals of a diverse, open economy. Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman was singing a song that all wanted to hear.

The plan to reform Saudi Arabia to moderate Islam might be well underway, despite that the term has yet to receive an official definition by the Saudis. The assumption is that moderate Islam will equal a Kingdom that values social progressive reforms, has fewer gender restrictions, and that distances itself from the regressive and aggressive Islamic doctrines of Salafism and Wahhabism, both of which have been essential to keep the modern state of Saudi Arabia intact.

Prince Salman has long been held as a could-be reformist, and closer to Western values than his father, King Salman. Domestically, the Prince has made inroads towards introducing progressive policies. Yet, his true ambitions and attitudes can best be seen outside of the Kingdom. As always, actions speak louder than words.

Less than a month after Prince Salman made his vow, the world got to see the new crown prince in a very different light. Upon orders from the Prince, family members, military men, and business tycoons were arrested and imprisoned across the country. It appeared that the crown prince was cleaning house. Amidst the hope of a better Saudi Arabia, no one dared to object.

No doubt the promise of moderating the country, along with the perception that a new King Salman with absolute power would ensure Western influence in the Kingdom for generations to come, helped ensure that no one would question his rise to power.

Terrorist attacks can shake the foundations of our biggest buildings, but they cannot touch the foundation of America. These acts shatter steel, but they cannot dent the steel of American resolve.

-George W. Bush

Peace in Our Time? Enter: The “Global War on Terror”

In a 2016 study, the Global Peace Index reported there are only 10 countries in the world that are actually free from conflict. The conclusion is that we are further now from world peace than at any time since the end of the Cold War. It has gotten to the point where even those that get paid to keep track of conflicts, find it hard to keep track.

“The West is winning the battle against the Islamic State, but losing the war,” said The Diplomat. There are so many wars, real and fabricated, to fight these days that I have basically lost count.

“Which one are you referring to?” I asked. “The War Against Terror,” he responded. The “Global War on Terror” is about as well defined as the war on Christmas. To some it is an absolute, to others an abstract. The prevailing thread is, however, that the modern definition of terror as perceived by the West at large is that we are fighting against such entities as al Qaeda and the Islamic State. Both enemies belong to the Salafist Jihadist school of adherers.

The first enemy in the Global War on Terror was, of course, al Qaeda (which means “the base”). Created by Osama Bin Laden, the son of a Saudi businessman, Bin Laden was a known enemy of the United States for nearly a decade before the September 11th attacks. The attacks had been planned from a small compound in the hills of Afghanistan, a compound that had been provided by the Taliban in exchange for money and some troops. Well known to the American intelligence community, direct action against this compound was suggested on multiple occasions. Hindsight is a marvelous thing.

It was this enemy that struck the towers in New York City that fateful morning. The attacks would spark the conflict dubbed “the Global War on Terror,” a catchy American phrase that drew criticism. Thousands have died avenging the lives of the 2,977 people killed at the World Trade Center and the Pentagon. Many more have died because they were in the wrong place, at the wrong time. Like, for instance, their living room in Fallujah, Iraq, when any which side in this war happened to decide to engage the other which side nearby.

The 9/11 attack changed our perspective of the world, and our place in it. It changed everything, as it is so popular to say. But as things often are, “everything” only includes so much. American core policies, foreign and domestic, remained largely the same. Often times they were given a new coat of paint, or were enhanced with anti-terror language, making them stronger and more versatile than ever.

The immediate reaction to the 9/11 attacks was understandable and predictable. The default American reaction is often not as important as what the action might be, so long as there is action. And with that, American Special Operations units began swarming the hills of Afghanistan, quickly dismantling what little organized and static framework the Taliban had set up to govern with. By September 14th, the Taliban held capital of Afghanistan, Kabul, was captured by the United States-supported Northern Alliance (NA). In the process, NA had lost 528 of its men. The Taliban lost 2,314.

Big Pentagon soon followed suit. Tanks, unarmored Humvees and thousands of fighting men from the Western world deployed to root out the enemy, an enemy defined as members of the Salafist Jihadist organization known as al Qaeda, and its ally the Taliban. The majority of the enemy leadership was able to escape into neighbouring Pakistan, or retreat into the remote mountainous regions.

That was over 16 years ago, and America has never been further from winning the war than it is today. What began as a relatively straightforward affair, has now become a knotty dilemma where the enemy has evolved into something stronger, smarter, and more resilient than ever. In fact, today we hardly even know who the enemy is.

The Tale of Gregor Samsa, a Traveling Salesman

“We need to redefine the enemy,” my friend said, “and maybe redefine some so called friendships as well.”

The enemy that struck the United States on 9/11 is long gone. The organization that today carries the name al Qaeda is a very different entity than that which sprung from the mind of Osama Bin Laden and the Egyptian Islamic Jihad movement in the early 90’s. What has taken its place is something much worse.

If the West is losing its de facto war against Salafist Jihadist extremism, then it is doing so by misunderstanding and ignoring the origin and complexities of the enemy. The West has failed to grasp its immensity, and how strong and ingrained it has become.

The premier failure lies with the United States, as the de jure leader of military and cultural definition of the West. The US, and its Western allies, continue to largely treat the enemy as a set of regional tactical conditions, when the reality is that it is a set of globally strategic conditions. This, is in part, because of how culturally far removed the average American remains from the actual battle, and how incompatible the enemy is with American values.

The West needs to redefine its understanding of its enemy. The global Salafism movement has grown. It does not just comprise widely known groups such as al Qaeda or the Islamic State. It consists of individuals across the world, who seek to stop the developing progressive Muslim societies around the globe. Never before has the US faced opposition of this ferocious magnitude.

While the Salafist movement is, by its intent and scope, an enemy of the West, the West is not the Salafist movement’s primary enemy. The real enemy which they seek to destroy, is the growing number of progressive Muslim communities. These communities represent viable, often Westernized, values and non-traditional possibilities more in tune with the overall direction that the world is moving in. As such, the militant Salafist movements do not threaten to necessarily destroy the West – not yet at any rate. Instead, the common primary goal is to disrupt and destroy these progressive Muslim communities and replace them with “true” Islamic societies as per the fundamentalist and puritan Wahhabist and Salafist interpretation.

Today, Salafist militant movements have become arguably more apt in functioning as a state’s drop-in replacement. The perfect example of this development is the al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP) movement. AQAP appears to have taken a chapter out of the gamebook of the Lebanese Shi’a militia group Hezbollah. As Yemen descended further into a part secularist, part traditional political power-based civil war, the Salafist Jihadist movements emerged as alternative stabilizing factors, even providing social benefits and community frameworks.

While al Qaeda remains loyal to its severe interpretation of Sharia law, and how the world should be shaped in its image, it has arguably become relatively more moderate, at least compared to some of its Salafist peers and competitors. This has caused certain fringe elements to break away from the group, and emerge as functioning independent groups. At times those new groups have retained affiliations with their former parent organization, but often they have instead considered al Qaeda and its leadership as too moderate or even kafiris, or infidels.

The Times They Are A-Changin’

In the aftermath of the last Iraqi war, Shi’a Muslims gained control over the government in Baghdad. This meant that Iraq’s rich oil fields were now under control of people often described as affiliated with Iranian interests.

Similar developments had already largely happened in Lebanon, where the cohesiveness of the Beirut government is largely at the mercy of the surrounding Shi’a militia movement and their political allies. By 2011, the Arab Spring resulted in Sunni populations across the Middle East perceiving themselves to be under threat, real and perceived, from Shi’a, Kurd, anti-Islamist factions, Russia, and others. In response, many less progressive Sunni communities across the world began supporting militant movements.

The Salafist movements went into overdrive. The Syrian civil war, in part a result of the instability that the Arab Spring brought with it, was the perfect vacuum for breakaway factions to emerge and establish themselves as separate entities. This included the Islamic State, a breakaway faction from al Qaeda. The Islamic State interpretation of Salafism is more firmly rooted in the puritan values of the Wahhabist movement than its parent organization.

The militant group quickly gained terrain, causing devastation to the old and new Shi’a spheres of influence. The Islamic State took control over the cities of Deir Ezzor and al Raqqa in Syria, both with vast oil fields and of immense logistical importance. In Iraq, the group took the Qayyarah oil fields and refineries, as well as the Baiji refinery. The Islamic State controlled areas were well aligned with the availability of oil that had previously been under Shi’a control.

This created a situation ideal for the largely Saudi controlled OPEC, which profited greatly from the interference.

Saudi Arabia did not just profit from the oil revenues, which were channeled into a de facto oil war against the West and the emerging market of unconventional oil and gas production, but also through the strain on their Shi’a arch enemy, Iran. Saudi Arabia may or may not have directly financed members belonging to the Islamic State, but it certainly has benefitted from its existence and actions.

Keep your friends close,

and your enemies closer.-Michael Corleone, The Godfather Part II

Investing in Saudi Arabia

Henry Kissinger once famously quipped that “America does not have friends, it has interests“. It is in the Middle East that his statement rings the truest. This region has famously been one of, if not the most, turbulent in modern history. To survive, even thrive in such a place America needs allies with mutual interests.

For over fifty years, the defining Arab ally in the Middle East has been the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. The consumer grade truth of the American alliance with Saudi Arabia is a wistful thing that harks back to the Eisenhower administration. The post-war US economy was doing quite well, and to safeguard its continuing supply of resources the Eisenhower administration began supporting a variety of power blocks across the world. The most famous examples were the so called “Banana Republics” in the Americas.

The Middle East soon went from being a distant place, to one that America had immense interest in. This interest was justified through a series of media campaigns by Washington and the industrial sector alike. Iran, Israel, and Saudi Arabia were the talk of the town. The smart money was on oil. Just as had happened a hundred years earlier during the California Gold Rush (1848-1855), entrepreneuring individuals rushed to the Middle East to make an empire for themselves. The immense resources that these countries held would safeguard the emerging American Empire until the end of days. Investing in the future was investing in the Middle East.

Soon, the Kingdom became the go-to choice for such investments.

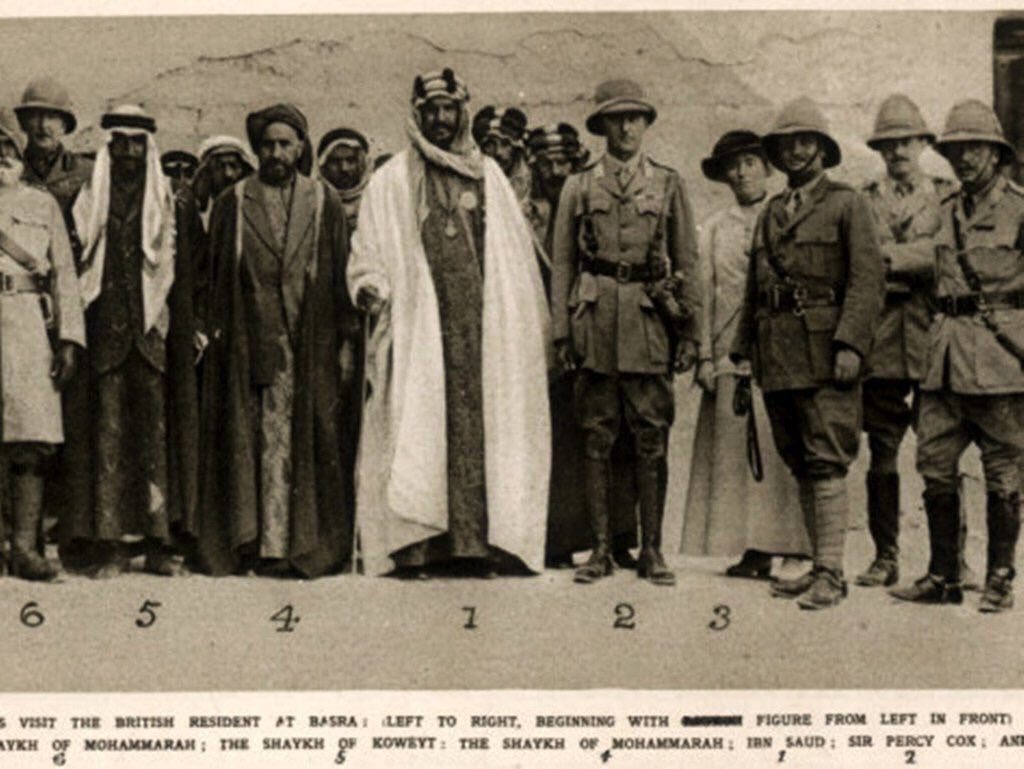

Saudi Arabia has had a “favored nation status” relationship with the US since 1931, when the US recognized Saudi Arabia, and its ruling class – the House of Saud. King Ibn Saud, in exchange for this, granted the US company Standard Oil of California, today known as the Chevron Corporation, the exclusive right to explore the Eastern Province for oil. Standard Oil also paid the Saudi government £30,000 and hired extensively from the Saud family to fill its local executive ranks. A local Saudi-company was established, part of the Standard Oil corporate structure, called California Arabian Standard Oil Company (CASOC).

At the time though, the agreement between the two nations was primarily that of mutual financial interest, and the US operated all diplomatic relations with Saudi Arabia out of its Egyptian embassy in Cairo. It would take until 1943 for the US to establish its first resident ambassador, and fully functioning embassy.

Between 1941 and 1945, the total output from CASOC’s fields remained quite low, estimated at 42.5 million barrels, less than 1% of the output of domestic US fields. But the American engineers at the company reported that they believed the country had vast oil resources that remained untapped. As such, by 1945 the US government set out to ingrain itself with the Saudis. US President Franklin D. Roosevelt met with King Ibn Saud during the Yalta Conference in 1945, and offered to provide American military might to safeguard the King’s family over Saudi Arabia for the foreseeable future. In exchange, America would buy Saudi oil for a tuppence.

As the post-war lines of influence, both commercially and politically, were drawn and became fixated, the other shoe dropped. The 1950s and 1960s were a turbulent time for the Middle East. The world would witness the advent of political Islam, the last twitches of the dying European empires, and a series of destabilizing military coups which unseated the old power houses.

In Egypt, President Gamal Abdel Nasser advocated a pan-Arabic power block, at the expense of the former ruling classes. President Nasser’s approach became known as Nasserism, and combined the use of Islam for political gains along with Arab socialism, equaling military totalitarian governing.

Fearing that the Cold War tensions emanating from Egypt would spread, unseat existing powers, and install Soviet-backed powers in the region, the US doubled down on its military and financial interests with its regional allies. In Jordan, for example, the US helped young King Hussein set up an intelligence agency and military guard under his control. This would hold the US in good stead with the Jordanian royal Hashemite family, as both have served to safeguard the lives and reign of the family multiple times.

Despite these investments, the region, in particular the Levant soon began to unravel. Nasserism in turn led to the royal Hashemite house in Iraq falling, along with Syria falling to military dictatorship. Those nations that did not fall saw immense increase in domestic radicalism, and even states of near civil war.

The blowback of the advent of political Islam, dying empires, and emerging new international power dynamics, now filled the region. With regional stability questionable, only a handful of stable investment and resource supply options remained. Saudi Arabia emerged as a premier choice.

By the late 1970s, siding with Saudi Arabia was not a choice – it was a necessity. This despite the fact that the Saudi-led Organization of Arab Petroleum Exporting Countries (OAPEC), consisting of the Arab majority of Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) plus Egypt and Syria group had carried out a large scale oil embargo against its allies, the US and other Western nations that supported Israel in the Yom Kippur War. In light of the outcome of the Iranian revolution in 1979, the West simply had no other choice but to rely on the Saudis.

I saw a report yesterday. There’s so much oil, all over the world, they don’t know where to dump it. And Saudi Arabia says, ‘Oh, there’s too much oil.’ They – they came back yesterday. Did you see the report? They want to reduce oil production. Do you think they’re our friends? They’re not our friends.

-Donald Trump

[Oil] War Is Declared

It is only natural that ground warfare in the Middle East will focus on controlling the oil rich areas or the areas of operations. Next to water, oil is the most precious commodity in the region. As such it comes as no surprise that if one superimposes a map over the terrain held by the Islamic State at its peak, it would form a near perfect alignment to the oil rich areas in Syria and Iraq. There are many ways to gain legitimacy in the region and the world. ISIS sought to gain legitimacy militarily, religiously, politically, and resource-wise. Revenues from the regional black and gray market oil sales would also support its growing numbers.

The Syrian Civil War gave a new generation of Jihadists the chance to thrive, which lead the Islamic State to break away from al Qaeda and become an independent entity. In the vacuum that the Syrian conflict created, ISIS quickly acquired vast territory under its control. Soon ISIS moved onwards, into Iraq. By late 2014, the amount of terrain that the group controlled peaked.

The majority of the oil and gas fields that ISIS controlled, or sought to attack, were those held by Shi’a interests. With Shi’a controlled oil fields in Iraq, Syria, and Yemen in a state of crisis, Saudi Arabia saw an opportunity. The Kingdom’s market share had been quickly eroding, largely due to domestic American production, increasing Russian oil sales in Europe, and the prospect of Iranian oil flooding the market in a near future. Saudi Arabia then attempted to steer the market through overproduction. This was a dramatic departure from previously deployed strategies, which had successfully brought the West to its knees through a series of energy crises in the 1970s. The 1973 oil crisis, and the 1979 energy crisis, had proven to be successful displays of the power that the Saudi Arabian led OPEC held over the world.

The Chinese use two brush strokes to write the word ‘crisis.’ One brush stroke stands for danger; the other for opportunity. In a crisis, be aware of the danger–but recognize the opportunity.

-John F. Kennedy

With Saudi Arabian oil production output reaching record levels in 2016, it attempted to keep global supply high and prices down. Saudi Arabia wagered that it could outlast and outspend its competitors all the way down. To support this tactic, the Riyadh government chose to tap its foreign exchange reserves of $746 billion dollars. As a result, between 2014 and 2016 the reserves dropped to $536 billion, a loss of nearly a quarter of a trillion dollars. Analysts believed that if the country continued at this pace it would have been bankrupt in under 8 years.

While this act of production warfare did severely damage the domestic American shale industry, as well as regular production profit margins, it did so with the unintended effect of making producers more intent on cost-cutting, automation, and increasing production efficiencies to find an earlier break-even price point. Russia in turn took a more traditional approach, and met the Saudi challenge by doing much of the same. Seemingly, Russia quickly saw what was happening, and knew that if it could sustain its output it could gain more than it had lost. Iran has yet to focus its oil producing industry beyond its domestic and regional scope, and thus the Saudi endeavour did little to cause lasting damage.

Saudi Arabia has for years recognized the need to escape its financial dependency on oil production. If the strategy of overproducing had worked, if it had managed to knock Russia, the United States, and Iran out of the loop, it could have created an immense financial buffer. This buffer could then have been used to finance the spendings deemed necessary. But by mid 2017, it was obvious that while the Kingdom had won by crippling the American oil industry, it was nothing but a Pyrrhic victory.

The Kingdom was now the loser of a war it had started, and its own greatest victim. Instead, this war appears to have been won by Russia.

Saudi Arabia, Wahhabism, and Salafism

“It all began in Saudi Arabia,” The Diplomat said, while pouring another double of Glenfiddich 21 year old scotch that I had generously bought.

I have always been one to ply my friends and foes alike with reasonably priced premium spirits, to make their tongues loosen. Admittedly, it often has the same effect on me as it does on my victims.

The history of Saudi Arabia, Wahhabism, and Salafism is one that is heavily intertwined. In fact, the modern state known as the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia could not exist without Wahhabism. The majority of the Salafis in the Gulf states reside in Saudi Arabia, and are the “dominant minority” in Saudi Arabia. In 2012, a Saudi government report indicated that there are 4 million Saudi Salafis, equaling 22.9% of the Saudi population. The majority of these adherers are concentrated in Najd.

In 1902 the House of Saud created, under the leadership of Sheikh Aziz, the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. This was accomplished with the help of Wahhabi religious leaders who traded their tribal fighters, called the Ikhwan, in exchange for the promise that the House of Saud would propagate their beliefs. Once the land had been conquered, the Ikhwan turned against the House of Saud, resulting in Sheikh Aziz turning to the religious leadership for a ruling on who should rule.

The leadership ruled in Aziz’s favor. To cement the family power, Sheikh Aziz declared himself king, and married the daughter of every tribal leader in the country, fathering 45 legitimate sons. The total number of daughters, or illegitimate sons, is not known. In addition, he made a grand statement of forgiving the Ikhwan. While the House of Saud under Sheikh Aziz was not overly religious, it needed the Ikhwan troops of the Wahhabi persuasion.

Wahhabis believe that theirs is the true faith, Islam in its purest form. Wahhabis live by a staunch and exclusive dogma that mirrors the Taliban in its intensity, although the message differs. Anything that differs from the Wahhabist belief is regarded as objectionable and unholy. The preferred titles of the Wahhabi believer are “al-Muwahhidun,” or “Ahl al-Tauhid,” meaning “the Asserter of the Divine Unity”. Tauhid is considered to be the very foundation of Islam, the defining core values and purity in its essence. Any deviation thereof would be wicked, corrupt and evil. This is also where the al-Ikhwan al-Muslimun, or “The Muslim Brotherhood” gets its flare.

It is always good to know that our best allies in the region have some overlap with our friendly like-minded groups across the region.

Both Wahhabism and Salafism are reformist and revivalist movements associated with the Sunni belief, and originated in the 18th century. While they share many common threads, such as the influence of the ultraconservative Islamic scholar Muhammad ibn Abd al-Wahhab, from which Wahhabism gets its name, Salafism relies significantly heavier on al-Wahhab’s orthodox teachings.

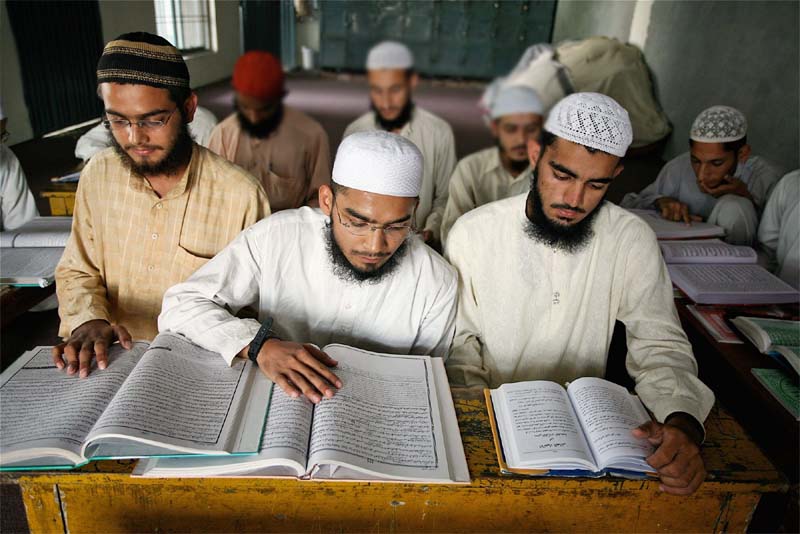

These more orthodox teachings include the topics of a religious-political approach to the legal system, and ideal placement of Islam as a dominating entity across the board. While they originate from the same founding philosophies, the Salafist movement is significantly more stringent in its adherence to the liberal and puritan reading of sacred texts, resulting in a strict conservative conformity with starkly austere overtones.

Whereas even Wahhabists will at times discuss the latest films and tv shows, adherers to Salafism radiate an abhorrence of popular culture, instead favoring the enactment of the traditional Islamic codes of behavior such as the seclusion and covering of women, and praying five times a day. In fact, the differences in the cultural and way of living between the average Wahhabi and Salafist can appear with such disparity that it borders to comparing the Wahhabist with the generic Western culturally oriented Muslim. This divide is quickly causing a widening rift between Muslim communities, and the cause of a sense of alienation.

With the exception of historians focusing on Qur’anic history, or the historical empires of the Middle East and North Africa region, Salafism gathered little attention in the West before the events on the 11th of September, 2001. The topic of “fundamentalism” and all that it entails had been a topic of interest for academia inclined Western individuals since the assassination of Egyptian President Anwar Sadat in 1981. But even those that specialized in the abstract topic of fundamentalism often neglected the topic of Salafism, and its roots.

Those few that did make an effort to carry out an in depth study of modern Islam as a political instrument and militant movement point of view often considered it a mere extension and historical devise to excuse modern day activities. Often times, Salafism was considered a mere addition to the ideology of the pan-Islamist political movement known as Hizb ut Tahrir, which seeks to re-establish the first caliphate to unify the Muslim communities under Sharia law, the Rashidun Caliphate, which existed between 632–656. At best, it was considered an anthropologist interest of little consequence. Most serious studies done on Salafism were instead done in Saudi Arabia where they overlapped with the study of Wahhabism, an ideology that the House of Saud rests its foundation for its power base upon.

The modern day Salafi-Jihadist doctrine came as a direct result of the politicalization of Islam during the 1950s and 1960s, a time period where politics and Islam created an amalgamated belief system that sought to use the fervor of religion to further local strongmen’s pan-regional power aspirations.

![Image Moroccan Salafists at a 2011 protest against the state [Imrane Binoual]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/Les_salafistes_djihadistes_lancent_une_campagne_de_révision_au_Maroc_6162420153.jpg)

At this point, the modern definition of the term jihad has become synonymous with Salafist militancy.

If you see the black flags coming from Khurasan, join that army, even if you have to crawl over ice, for this is the army of the Caliph, the Mahdi and no one can stop that army until it reaches Jerusalem.

-Khurasan Hadith

While the two paths have come to differ in varying degrees, ostensibly both Wahhabism and Salafism have retained their core belief; the ultimate duty for every true Muslim is to seek the creation of a modern day caliphate, in the image of the first ever caliphate.

Another core value of Salafism is the strict literalist approach to the Qur’an, as well as the accompanying Hadiths. This despite the fact that many of the key hadiths used to support Jihadism lack official Sanad (official translation), but have more generally agreed upon meanings and wordings.

One such example is the infamous “Black Flags of War coming from Khurasan”-hadith:

“If you see the black flags coming from Khurasan, join that army, even if you have to crawl over ice, for this is the army of the Caliph, the Mahdi and no one can stop that army until it reaches Baitul Maqdis.”

(Baitul Maqdis means modern day Jerusalem). The hadith was allegedly originally narrated by Abu Hurayrah, one of Mohammed’s original sahabah (meaning disciples), and while the translation is considered reputable it is not a Qur’anic-level scholarly official translation.

Many influential Muslim scholars question the authenticity of the hadith, including the influential Saudi cleric and Muslim scholar Salman al-Oadah. Al-Oadah was jailed at one point for opposing the House of Saud’s invitation of US troops into Saudi Arabia mid-1990, to stabilize the region in response to Saddam Hussein’s invasion of Kuwait, resulting in the first Gulf War. Osama Bin Laden, as the leader of al Qaeda, publicly supported al-Oadah in his opposition to American troops in Saudi Arabia, but al-Oadah never reciprocated this support. Instead al-Oadah firmly opposed al Qaeda, and became a vocal critic of such groups throughout the Middle East.

“The hadith about the army with black banners coming out of Khurasan has two chains of transmission, but both are weak and cannot be authenticated. If a Muslim believes in this hadith, he believes in something false. Anyone who cares about his religion and belief should avoid heading towards falsehood.” – Salman al-Oadah

The so called black flags, or black banners depending on translation and intent, have as a result of such hadiths been the go-to core image that most Salafist Jihadist movements use. It harks back to one of the battle flags that Mohammed allegedly flew during his military campaigns. As such it holds significant religious and propaganda value to individuals with suitable leanings. In some aspects, it can even add legitimacy.

Inside the various Salafist militant groups, the selecting of suitable hadiths and interpreting their meanings to support the overall mission of the group, is a key position. In recent years, counterinsurgency efforts have been made to neutralize individuals in such positions. For example, Anwar al-Awlaki (killed September 30, 2011 in Yemen, member of al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula) and Turki al-Binali (killed May 24, 2017 in Syria, member of the Islamic State).

Another example of such an hadith is the one that dictates that Jihadists should let their hair and beards grow out. “The black flags will come from the East, led by mighty men, with long hair and long beards; their surnames are taken from the names of their hometowns and their first names are from a Kunya.” Kunya, in this context, meaning nom de guerre, a fictional first name taken to be used at time of war. Again, this hadith has a dubious origin and is not acknowledged by many non-Salafist movement authorities.

There will be boots on the ground if there’s to be any hope of success in the strategy.

-Fmr. Defense Secretary Robert Gates

Kumbayemen my-lord, Kumbayemen …

Under a Saudi-led coalition, a total of nine African and Middle East countries have joined a military intervention against the Iranian proxy militia known as the al Houthi movement in Yemen. The intervention will soon have gone on for three years, and cost the lives of over 13,000 people.

What began as a local war has become a free-for-all proxy war. One of many that came in the backwaters of the Arab Spring movement, has reached the international stage.

While the coalition has primarily focused on carrying out airstrikes against believed al Houthi ground targets, the Kingdom knows that only so much can be done by mercillessly striking its foe on the ground. Traditional military thinking is that war is won by the boots on the ground, and the post-war build-up of the conquered nation.

Saudi Arabia has fielded a reported 150,000 troops in total, with other coalition members having fielded an estimated 12,000 troops, for ground operations. Ultimately though, the Kingdom is putting its faith not on traditional military thinking, but the alternative tactic of establishing Salafi-Wahhabi teaching centers as a counter balance to the rural al Houthi Zaydi teachings. This is a tactic that has in the past proven useful, and at times an excuse for military action, for the Saudis.

The Saudis have, for well over thirty years, been maintaining Salafist-Wahhabist educational centers, so called madrassas, throughout, among other places, Yemen. During the turbulent 1980s Saudi backed militia movements recruited heavily from these centers. Many jihadi insurgents with schooling in Yemen have either studied, or trained at these centers.

The most famous center was the Dar al-Hadith, or “house of the Prophets sayings and deeds,” which was founded by Sheikh Muqbel bin Hadi al-Wadie (1933-2001). Sheikh Muqbel is widely described as one of the fiercest anti-Western Islamic clerics to ever have emerged, and his madrassa is believed to have trained well over 4,000 militant Salafist Jihadists. While the school was originally supported by the Saudi government, this changed after Osama Bin Laden became directly associated with the school. Since then, the Saudi government insisted that any support the center receives comes from private Saudi individuals. Sheikh Muqbel died in 2001, in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, after a prolonged illness and hospital treatment in Saudi Arabia, Cologne, Germany and Los Angeles, California, from either cirrhosis or liver cancer.

It was one of these Salafi-Wahhabi centers that played an intricate role in the beginning of the Civil War. In 2011, the Dar al Hadith center in Dammaj, near Saada City, was attacked by al Houthi militia forces. Then President of Yemen, Ali Abdullah Saleh, struck back by sending in the military to the area. Ultimately the center was closed down in 2014, and its adherers ordered to leave Saada as part of a civil peace agreement between the Saudi-affiliated Yemen government and the de facto Houthi government.

The centers had long been a focal point for Western intelligence and law enforcement agencies, including the US Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI). Between 2008 and 2011 many of these centers were forced to shut down, in light of the Yemeni security services cracking down on the growing number of safe havens for jihadists, such as members of al Qaeda, in the country.

As of 2017, few of these Saudi-supported centers remained in Yemen, mainly because of the volatile nature of the sectarian civil war that is tearing the country asunder, but also because of the perception that these centers are closely affiliated with Jihadist movements. But as the Saudi-supported Hadi government is gaining foothold, that is now set to change.

“Over the past forty years, the Saudi government has invested heavily in Salafi-Wahhabi-style madrassas and mosques in the northern areas, only to realise that this programme was jeopardised by the Zaydi revival movement. If the Houthis were to be defeated in their home province, it is likely that the Salafi-Wahhabi programme will be revived, and implemented more fiercely than in previous years”

– Gabriele vom Bruck, Islamist scholar specializing in Yemen, SOAS University of London

Apparently, the Saudi government has plans to open an all-boys Salafist-Wahhabist missionary center in the city of Kashan, in the Yemeni province of Al-Mahrah, located on the border of Oman and Saudi Arabia. This area has long been part of an arms smuggling logistics line, as well as a jihadist gathering point.

70% of the Saudis are younger than 30, honestly we won’t waste 30 years of our life combating extremist thoughts, we will destroy them now and immediately.

-Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman

The Neverending Story

The human landscape in Saudi Arabia is quickly changing, with a growing number of young citizens falling into the categories of being unemployed, unemployable, or uneducated per Western standards. This in and of itself could be the one issue that a prospective, large-scale reform movement could not overcome.

The Crown Prince’s ambitions are reliant on near instant success and on a white-collar industry taking root, at the expense of the existing social dynamics. Such changes would cause severe frictions within the communities in the best of times. While some will advocate progressive notions, others fall back into the comforts of fundamental religious beliefs. The largest segment, and winner, in that divide will be decided based on job opportunities.

With this coming divergence in mind, a potential reasoning for the war drums against Iran steadily beating louder becomes more clear. Ostensibly, a war with Iran would ultimately benefit the Saudi ruling class, primarily its new incoming leader, the soon-to-be King Salman. By engaging in the age old tactic of defining an external enemy, through the shaping of dialog, the Prince will ensure a united Kingdom when he soon accepts power.

If an overt showdown with Iran were to happen, the Kingdom would no doubt first seek to use proxy militias, and involve the US military. If so, the Saudi call for US aid will no doubt come in a similar configuration as it did during Gulf War I, where the Saudis and Kuwaitis covered a majority of the expenses incurred.

The US Department of Defense has estimated the cost of the Gulf War at $61 billion. Kuwait, Saudi Arabia and other Gulf states covered $36 billion. A total of $53.5 billion was paid by foreign contributors. Because of this, the first Gulf war was the cheapest war the US ever fought.

“Within the halls of power in the West, the Saudi incursion into Yemen is often jovially talked about in the context of the Vietnam or Afghan war. It is not entirely out of the question that grand-strategists in the West, behind closed doors, are applying the same mentality that helped extend the Iraq-Iran war from 1980 through 1988. By enabling the Saudis towards engagement in a war against Iran on multiple fronts, a scenario is created, where the resources of both sides are quickly degraded through a slow-burn. The result is a point where they essentially neutralize each other. At the same time, the devastation of various Shi’a and Sunni militia groups may be assured. This would serve long-term, non-humanitarian Western interests.”

– Excerpt from Rock the Casbah – The Saudi Coup That Never Was, Lima Charlie News

Saudia Arabia has been racing to upgrade its military arsenal. In the last two quarters of 2017, it announced a series of arms purchases totaling nearly $122 billion. In May 2017, the Kingdom signed a letter stating that it intended to purchase $110 billion worth of weaponry from US firms. The deal includes at least $7 billion worth of just precision guided munitions from Raytheon Co (RTN.N) and Boeing Co (BA.N).

During the same period Saudi Arabia signed arms deals valued at over $3 billion with the Russian Federation. The Saudi Arabian Military Industries (SAMI) signed a deal on October 4th with Rosoboronexport, the Russian state arms trader, for long-range S-400 Triumph air defense missile systems. Part of the deal is also that Saudi Arabia will be licensing the production of a series of Russian items, including the Russian Kornet-EM anti-tank missiles, TOS-1A rocket launchers, AGS-30 automatic grenade launchers and the latest version of the Kalashnikov assault rifle.

In total the Kingdom signed arms purchase orders, or letters of intent, valued at over $122 billion during the two last quarters of 2017. Some have theorized that the Saudis are functioning as a clearing house for all its allies, such as the UAE, Bahrain, and Egypt, in these deals. If they are not, it is doubtful that the Kingdom will be able to go through with the majority of the deals. Regardless, the prospects no doubt create headlines, show intent, and garner a great deal of goodwill from existing, as well as prospective allies, for a pittance.

“Regardless, if an eventual Saudi-backed war with Iran were to come, with the ongoing weapons deals with Russia, the economic warfare against our domestic production, and Saudi Arabia’s dubious affiliation with enemy groups … with friends like the Saudis … What do we have to worry about?”

And with that, The Diplomat emptied his glass.

John Sjoholm, Lima Charlie News

[Edited by Anthony A. LoPresti]

John Sjoholm is Lima Charlie’s Middle East Bureau Chief, managing editor, and founder of the consulting firm Erudite Group. A seasoned expert on Middle East and North Africa matters, he has a background in security contracting and has served as a geopolitical advisor to regional leaders. He was educated in religion and languages in Sana’a, Yemen, and Cairo, Egypt, and has lived in the region since 2005, contributing to numerous Western-supported stabilisation projects. He currently resides in Jordan. Follow John on Twitter @JohnSjoholmLC

Lima Charlie World provides global news, featuring insight & analysis by military veterans, intelligence professionals and foreign policy experts Worldwide.

For up-to-date news, please follow us on twitter at @LimaCharlieNews

Read Part 2: Lebanon: the Coming Uncivil War

In case you missed it:

![Image Saudi Arabia, al Qaeda and the Salafist Dilemma - Part 3 of the American Foreign Policy Review series [Image: Lima Charlie News]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/Saudi-Arabia-al-Qaeda-and-the-Salafist-Dilemma.jpg)

![The Art of Foreign Influence: The Russian Military Adviser [Lima Charlie News]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/The-Art-of-Foreign-Influence-The-Russian-Military-Adviser-480x384.png)