Part 2 of the “American Foreign Policy Review” series takes a look at our regional allies and foes and a region facing yet another civil war. Continued from Part 1.

Welcome to Beirut

November 22nd. Mere minutes after the stroke of midnight, a white private plane carrying the hope of a nation touched down on Runway 21. Armored police and military vehicles appeared by its sides and escorted the plane towards its disembarkation point on the eastern side of the airport. From this location, no one outside the secured airport would be able to fire against the plane using Rocket Propelled Grenades (RPGs) or precision rifles. The airport was utterly surrounded not just by police forces, but also by the Lebanese National Army (LNA).

Travelers inside the small but busy international airport knew nothing of what was going on. Suddenly there was a lull of several minutes — no announcements and no planes were allowed to land or lift-off. Men in black uniforms appeared out of nowhere holding machine guns and the LAT Lounge on the east side of the airport was shut down.

Onboard the plane was the runaway Prime Minister of Lebanon, Saad Hariri, and his life was in danger. A few weeks earlier, he had received an intelligence briefing in Riyadh that the Iranian militia Hezbollah was actively seeking to assassinate him. In response, Hariri had immediately gone on Saudi TV and announced his resignation, lamenting the situation and growing Iranian influence in his country. If the threat against his life proves true, Hariri’s return to Lebanon might be his end.

The plane had not yet come to a complete stop when Lebanese soldiers holding M4A1 Short Barrel Rifle (SBR)-configured weapons—provided by the U.S.—swarmed and surrounded the plane. Their black berets and unit patches indicated that they were from the Kouwa el-Dareba unit, an elite counterterrorism unit inside the Lebanese Special Operations Command (LSOCOM). Seconds later, men wearing the familiar beret and patches of the Maghaweer—the Lebanese Rangers Regiment—in one unified motion exited the black SUVs that were now encircling the plane.

Their rifles trained high, aiming towards the night, searching for foe unknown.

Give me a Place to Stand

I don’t feel any compulsion just to stand under the spotlight night after night unless I have something to say.

– Leonard Cohen

I often find myself visiting Beirut, the capital of Lebanon. It is a place that quickly comes to play a central role in your life if you work as a freelance intelligence operator or wannabe reporter. I spent 2005 to 2012 traversing the political and security topography throughout the region bouncing between war zones, conflict zones, and havens of commerce working on behalf of a variety of interests.

Beirut remains a premier hub to meet with people from all walks of life. Here, you can have breakfast with members of the Moukhabarat-al Jaish (Military Intelligence), lunch with Hezbollah, and evening drinks with a beautiful woman from Mossad. At the end of the day you likely either made coin or spent what coin you had. As a freelance intelligence operative, the goal was always to have your finger in enough pies and gain access to enough privileged information so you could profit from being more than a mere access agent. (An access agent is someone who has little value in and by themselves, but can be useful in gaining access to the people who have valuable information.)

Whatever poison you favor, Beirut has it in spades.

Another advantage is that the Western intelligence community—my primary client base—sends far fewer naive do-gooders (people whose ability to find water is limited to checking if their feet are wet). If sent, such individuals are forced to either learn how to swim or they sink very fast. You have to become yet another cynical bastard or disappear. Preferably their disappearance means that they went back home, to their natural habitat of the fluorescent light lit offices of Virginia or Washington D.C. Those that stick around quickly learn that real fieldwork rarely focuses on figuring out how things work, but instead on how people work. Those that become really good at the job quickly end up—in essence—professional Machiavellian tourists of realms where angels fear to tread. It was in this capacity that I went about my job; to observe, to analyze, but not advocate unless otherwise ordered.

It is nearly impossible to not have some degree of fondness towards this city. At least, as long as you don’t find yourself dead, inside a black plastic bag by the airport roadside. I reckon that what I always find appealing with Lebanon is that it is such an intricate and adaptable place. You find the whole Middle Eastern world represented to some degree in Lebanon.

The Israelis might bomb your press office on Tuesday. Hezbollah might blow up your cafe on Wednesday. A Christian militia might use your hotel lobby as their command center on Thursday. Armani might hold a fashion show on Friday. On Saturday, someone might blow up your embassy. By Sunday, all bets are off. Life in Lebanon continues at any rate — Armani’s fashion show be damned.

Friends today. Enemies Tomorrow.

Holding UN meetings together on Monday.

A Tale of Two Countries

Lebanon—Beirut in particular—is known for many things. Throughout the world, it has become known for its food and culture. Regionally, it is known for being home to some of the most beautiful women, and for high fashion. However, Lebanon is also known everywhere for its convoluted politics and war. To many Americans, it has come to be the definition of a treacherous land where the American giant comes to bleed at the hands of irregular fighting forces.

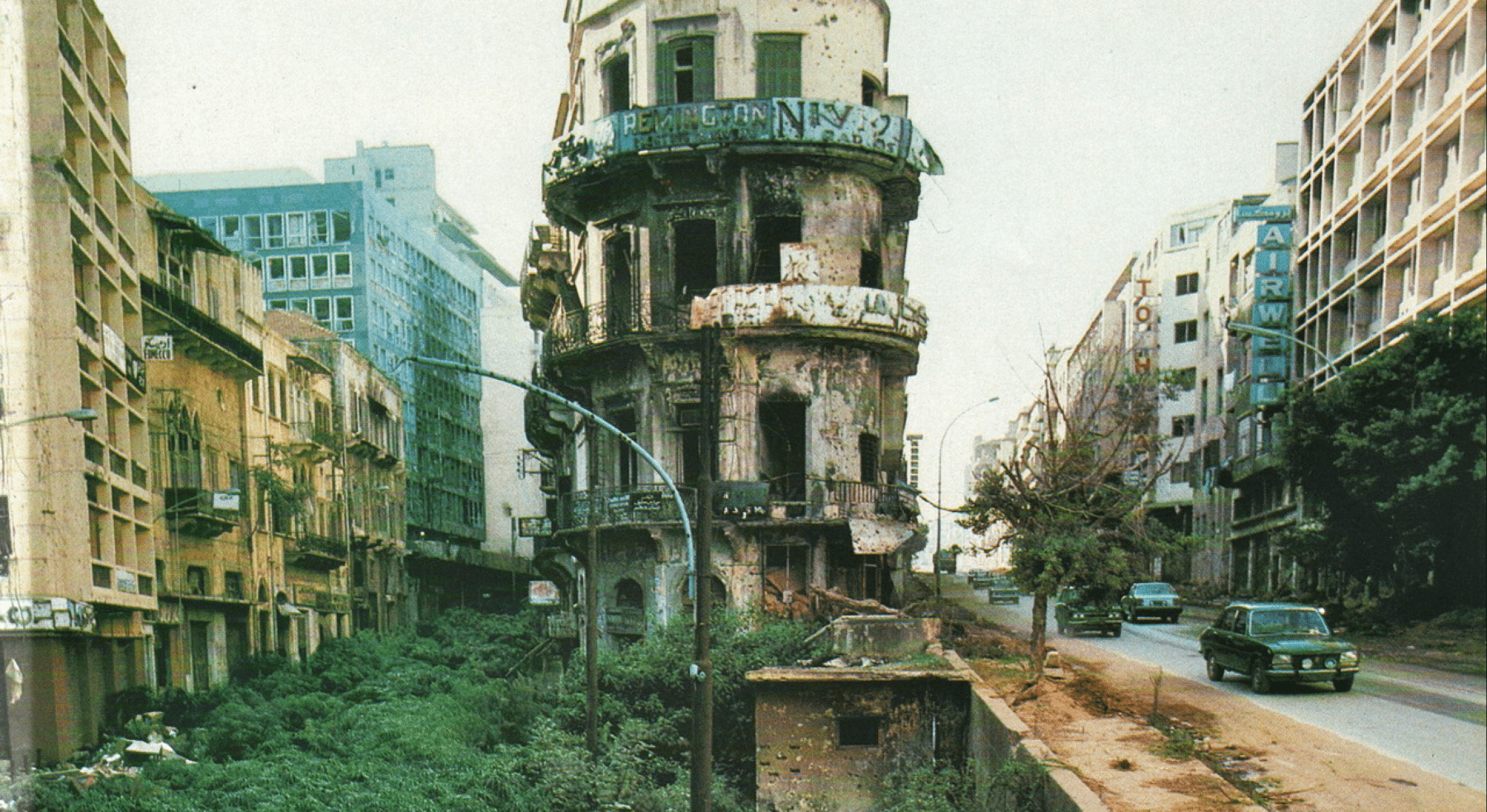

“Danger is in the mind of the beholder,” said the station’s customary old man to me, paraphrasing a line from Thomas L. Friedman’s book “From Beirut to Jerusalem”. And indeed it was. One can live perfectly well through war and conflict as long as one perceives things correctly and does not let it get to you. Lebanon is a perfect example of this. For 17 years, between 1975 to 1992, the country was engulfed in the flames of a civil war with little civility to it, endangering anyone and everyone that it could reach. While the civil war is now overtly over, covertly it never ended.

I would inherit a plaque from the old man a few months later when he left to move to France. It stated “Friends today. Enemies Tomorrow. Holding UN meetings together on Monday.” I hung it over the mess that my desk had become. There it remained until the Beirut operation was closed down by headquarters in Abu Dhabi, and the offices were scrubbed clean of any evidence that we had ever been there. Nowhere did the plaque’s message ring as true as it did during the Lebanese Civil War, although the never ending situation in Yemen did give it a run for its money.

April 13th, 1975. The courtyard of the St. Maron Church, situated in the Christian district of Rumaniyeh in Beirut, was filled with members from the right-wing Phalange Kataeb Christian militia. Militia members brandishing the Belgian FN made battle rifle Fusil Automatique Léger, more commonly referred to as the FAL, along with its German counterpart made by Heckler and Koch, the G3, were redirecting traffic away from the church area. Pierre Gemayel, leader of the militia as well as its namesake political party, was readying to speak to his men.

The topic of choice was the same one as it had been for quite some time: Lebanese national pride coupled with fear of the increasing number of Palestinians in the nation. The situation throughout Beirut was increasingly tense, with multiple militia groups arming themselves and preparing for war. All it would take was that last spark of hatred to ignite the situation.

In excited anticipation, the men inside the courtyard fired their rifles into the air in a celebratory move called baroud. Suddenly the gunshots heard were no longer coming from inside the courtyard — they were coming from outside on the street. A minibus carrying half a dozen Palestinian fighters from the Palestinian Liberation Organization (PLO) had refused to be diverted. A quick and merciless gunfight erupted between the Kateab militiamen and the Palestinian fighters. Who opened fire first remains disputed. But mere minutes later 4 people were dead. The driver of the Palestinian minibus sat dead in his seat, and around the minibus lay the 3 dead from the Kataeb militia.

The surviving Palestinian militia members retreated from the scene, and took up positions down the street, inside a nearby café. Within the hour, another bus arrived carrying more Palestinians. The Christian militia descended upon it and killed its passengers, 14 people in total. There is still an active dispute as to what the bus had actually been transporting. The Phalanges have insisted that the bus was carrying reinforcements to continue the attack, whereas the PLO still claims that the bus occupants had been civilians.

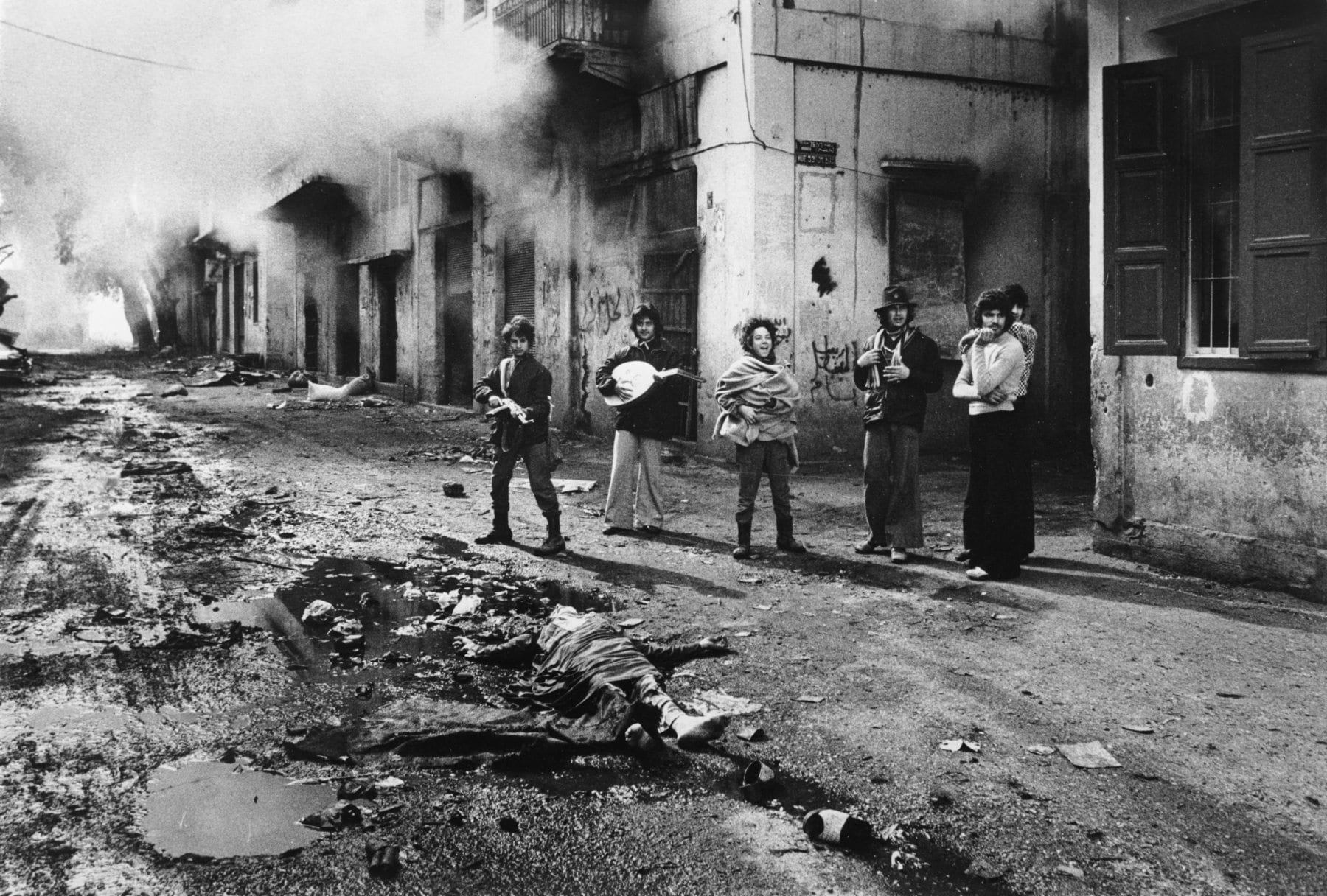

Word of the incident spread fast throughout the city. The spark of ignition into violence was complete. Before nightfall, factional animosity was out in full force, with Christian and Palestinian militia groups clashing. Groups of men, united by their enmity towards their fellow man, began carrying out search and destroy missions within their neighbourhoods. The tranquility of the moonless night was shattered, with the noise of fully automatic rifle fire filling its space. Throughout the city, civilians from all walks of life slept in their bathtubs, if they had one, hoping its metal or ceramic shell would provide some modicum of protection against a bullet gone awry.

The next day, April 14, 1975, the fighting spread across the nation. Soon battles erupted between militias at the key seaports of Tripoli, Tyre, and Sideon. Shops and banks throughout the country, especially in Beirut, were closed. Christian militia movements began setting up roadblocks in east Beirut, the Christian part of town, to stop Muslims from entering. In West Beirut, the Muslim part, militants from the PLO carried out their version of the same actions. By late afternoon, the civilian authorities had lost direct control of large parts of the capital.

With this in mind, the newly appointed Muslim prime minister Rashid Solh ordered Gemayal and his militia to stand down. The same order was also given to the PLO. Neither side adhered to his demands. By that evening, the government ordered detachments from its domestic security forces, the Force de Securitie de la Interior (FSI) to be activated to quell the situation.

On April 15, 1975, Gemayal met with the country’s Christian President Sulieman Franjieh in his hospital room. The President was recovering from surgery just hours earlier but was able to convince Gemayal to hand over the 2 men believed to have been involved in the killing of the Palestinian driver from the initial incident on April 14th.

The damage had been done, however. The Muslim Prime Minister was not backing down. The Christian militia had challenged the structure of the government and its power so, on the following day, April 16th, the fighting intensified. It was at this point that other Sunni militia groups joined the Palestinian militia, and smaller independent Christian militia groups sided with the Phalange Kataeb Christian militia. The government forces found themselves caught in the middle and began fracturing in favor of the different sides. Many civilians walking the street, looking for groceries, thought to themselves that this was as bad as it could get. They would soon be proven wrong. The third Lebanese Civil War had begun.

By 1976 the civil war had further intensified to the point where the world began noticing. Muslim and Christian militia groups began overtly targeting civilians, and President Fanjieh invited Syria to intervene in an attempt to broker a peace through force. With this invitation in their hands, the Syrian Arab Army (SAA) entered Lebanon. Their strategy of creating peace through occupation quickly proved faulty. Syria would soon discover that while one could ostensibly secure large parts of Lebanon, it could not control it, a lesson that the Israelis would learn the hard way a few years later.

It was during the Syrian incursion that the southern part of Lebanon became entrenched, with both Shi’a and Sunni militia groups solidifying their control of their enclaves there. Syria would never manage to truly control those enclaves, only disrupt them.

Sunni militia groups, largely under the flag of the PLO, began using their enclaves in southern Lebanon, towards the border, to attack Israeli settlements there. By 1978, the Israeli Army entered the fray. To some extent, the Israeli incursion into Lebanon ensured that the international community awoke to the dire realities on the ground. The United Nations quickly configured a force to send to southern Lebanon, where it has remained since, to attempt to pacify the warring parties.

The introduction of new blood to spill spurred the conflict on, causing the various non-state militia groups to surge in violence and lash out against anyone who dared oppose them. In response to this, the SAA began shelling Christian residential and militia areas in east Beirut.

Israel saw its opportunity, and offered an olive branch of support to the Christian militias, chiefly that of the Kateab militia. The US soon followed suit, offering overt humanitarian support and covert military support to the various Christian groups, along with its domestic ally, the Lebanese government. Other players, regional and international power players alike, began offering similar support for their representative militia groups. Iran supported a wide array of Shi’a groups and even refined several of them into a proxy-militia group called Hezbollah.

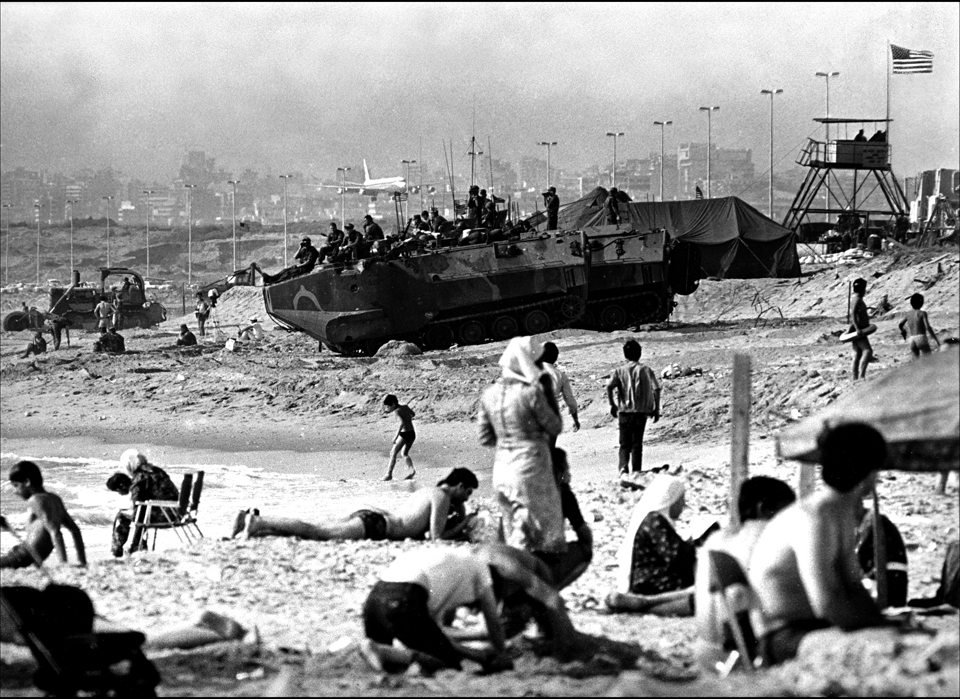

It was not until 1983 that the American public truly awoke to the harsh reality that there was a war in Lebanon, and that America was involved. By that point the third Lebanese Civil War had raged for 8 years, killing thousands and destroying vast portions of the country’s cultural heritage. But what was it that woke the Americans up? It certainly wasn’t that it was playing multiple sides in a multifaceted conflict where the straightest line possible was a circle. And it certainly wasn’t when the US sent nearly 1,000 Marines to participate in the Multinational Force in Lebanon (MNF). No, those aspects largely caught the American public unaware. It was the realities of asymmetrical warfare that woke America up, and this reality came, as it so often does, with a bang.

At 1300 hours, local time, on April 18, 1983, a van carrying 2,000 pounds (910 kilograms) of explosives crashed through the outer barrier of the US Embassy in Beirut. It detonated with an explosion that tore through the building killing 64 people. A few hours later, the American public woke up to the news that its castle in Beirut had been struck.

“All of a sudden, the window blew in. I was very lucky because I had my arm and the T-shirt in front of my face, which protected me from the flying glass. I ended up flat on my back. I never heard the explosion. Others said that it was the loudest explosion they ever heard. It was heard from a long distance away.

As I lay on the floor on my back, the brick wall behind my desk blew out. Everything seemed to happen in slow motion. The wall fell on my legs; I could not feel them. I thought they were gone. The office filled with smoke, dust, and tear gas. What happened was that the blast first blew in the window and then traveled up an air shaft from the first floor to behind my desk. We had had tear gas canisters on the first floor. The blast set them off so that the air rush that came up through the shaft brought the tear gas with it and also collapsed the wall.

…We didn’t know what had happened. The central stairway was gone, but the building had another stairway, which we used to make our way down, picking our way through the rubble. We were astounded to see the damage below us. I didn’t realize that the entire bay of the building below my office had been destroyed. I hadn’t grasped that yet. I remember speculating that some people had undoubtedly been hurt. As we descended, we saw people hurt. Everybody had this funny white look because they were all covered with dust. They were staggering around.

We got to the second floor, still not fully cognizant of how bad it was, although I recognized that major damage had been done. With each second, the magnitude of the explosion became clearer. I saw Marylee MacIntyre standing; she couldn’t see because her face had been cut and her eyes were full of blood. I picked her up and took her over to a window and gave her to someone. A minute later, someone came up to me and said that Bill MacIntyre was dead; he had just seen the body. That was the first time I realized that people had been killed. I didn’t know how many, but I began to understand how bad the blast had been.“

-Robert S. Dillon, then Ambassador to Lebanon, recounting the attack on the embassy

The shock and awe of that attack on the very essence of an American presence in Lebanon, the US Embassy, would soon be superseded.

In the early dawn of October 23, 1983, at 0622, a series of Vehicle Borne Improvised Explosive Device (VBIED) attacks was initiated when a hijacked 19-ton yellow Mercedes-Benz stake-bed truck crashed through the security gates of the USMC compound inside the Beirut International Airport. Driven by an Iranian national named Ismail Ascari, it was loaded down with 21,000 pounds (9,525 kilograms) of explosives.

The truck quickly breached the outer perimeter, and only one of the two Marines on sentry duty was able to chamber a round in response to the vehicle tearing through the concertina wire and gate. By the time that Marine, LCpl Eddie DiFranco, shouldered his rifle, the truck had already crashed into the USMC barracks entryway. Mere seconds later, the truck’s explosive load detonated. The lives of 241 American fighting men vanished in an instant.

Mere minutes later, a follow-up attack was perpetrated in much the same manner against the French 3rd Company barracks in Ramlet al Baida, 6 kilometers from the USMC compound. There, a speeding Honda pickup crashed through the concertina wire at the French perimeter. This time French sentries were able to engage the vehicle, killing its driver. However, because of the sheer size of it, and that the detonation appears to have been remote controlled, this did not save their lives. More than 500 kilograms of explosive material exploded, tearing through the perimeter and taking down the nine-story building. 58 French paratroopers died in this attack.

The October 23, 1983 attacks by Iranian supported elements killed 307 people, including the wife and 4 children of a Lebanese janitor at the French building. The attacks also killed any interest the US had in continuing its attempts to overtly participate in the Lebanese Civil War. The American public’s outcry was immediate, the notion of another American life lost in a war in a land so far away was deemed unacceptable.

Soon thereafter, due to popular demand, the American government waved a white flag and withdrew the bulk of its troops. Its European allies would remain throughout the war, but pay a hefty price for their participation. Soon thereafter, the recognized Lebanese government collapsed.

Some have argued that the Beirut Barrack bombings were a direct response to US warships off the Lebanese coast shelling Muslim areas of Beirut a few days earlier. The warships targeted Sunni and Shi’a militia group positions, in support of the Christian coalition militia and its control over the Lebanese government at the time. The reality is more likely that Iran and its proxies wanted to neutralize the Western powers before it went after the Israeli forces in Lebanon.

Soon after America’s withdrawal, all that remained were the European forces as part of the United Nations forces in Lebanon (UNIFIL), and the Israelis. The Israelis quickly became the premier target for all but the Christian militia groups. In response to this, Israel announced its withdrawal. But it would exact a bloody vengeance on the Lebanese for forcing their hand.

Months after the initial stage of the Israeli withdrawal, in September 1982, the Israeli affiliated Phalange Militia movement entered Palestinian refugee camps. The camps were surrounded by Israeli military observation posts. These massacres would become the first of many. Some of the exact details of what happened inside the camps are in dispute. But what is widely known is that at least 1,700 Palestinian refugees died at the hands of the Christian militia forces and that Israeli troops were given a front row seat to the massacre.

In the years that followed, Syria’s army would become the only foreign state player to remain, but it would suffer greatly at the hands of Sunni and Christian militia groups.

The civil war continued to rage between 1975 until 1990, a total of 15 years. Its toll on Lebanon is impossible to ignore. Its legacy still lay heavily over the whole country, and no political or military actions today are taken without some trace back to the original dynamics of the civil war. The truth is that the war is still very much an ongoing affair, and the players of it are still highly involved.

The Christian Phalangist militia commander, Elie Hobeika, agreed on January 22, 2002, to testify in a Belgian court about the massacres in the Palestinian refugee camps Sabra and Chatila. It had been Hobeika’s men that went into those camps in 1982 and carried out the series of murders, all under the watchful eyes of an Israeli detachment. Hobeika’s testimony was said to directly implicate Ariel Sharon, Israel’s Prime Minister at the time, who had previously been the Israeli Defense Minister and overseen large parts of the Israeli operations in Lebanon during the Civil War.

Two days after having agreed to testify, Hobeika’s vehicle exploded, killing him and 3 of his bodyguards. Israel quickly denied any involvement in Hobeika’s death. The death was instead claimed by a previously unheard of (and never heard from again) group called the Lebanese for a Free and Independent Lebanon.

Observers of Lebanon have in recent years pointed out that much the same dynamics and precursors that lead up to the Third Civil War are now playing out again. The tides appear to be returning.

Luck of the Soldier

April 2006. “Apple with mint, please,” said the design-label-wearing, gray-haired gentleman as he ordered his nargile. His suit stylishly intoned with his close-cropped hair. He defined the sense of style and peacocking only found in Achrafiyeh, in central Beirut.

“Georg” was a veteran of the Lebanese Civil War. He had done well for himself in the post-war years, becoming a well-educated economist and family man, as well as a great access agent. He and I often met for coffee and nargile whenever I was in town. During the Civil War, Georg had been a member of the Christian Phalangist militia. It was under the command of the militia’s leader, Elie Hobeika, that he partook in acts that would later be referred to as massacres. It was a description that Georg had little problem with, he himself using it often.

Georg was born into a Maronite Christian family in 1965. His father, named Jean, feared that the significant increase of Palestinian refugees in the country would unbalance the fragile Lebanese civility. By the late 1960s, the Palestinian Liberation Organization (PLO) and Yasser Arafat, its leader, fled from Jordan to Lebanon after a failed attempt to take over Jordan. The PLO quickly began establishing itself in Southern Lebanon, creating a new base of operations. From here the movement began attacking targets in Israel and opposing militia movements throughout the country. Jean was furious, and like many other Lebanese Christians joined the right-wing, nationalistic Phalanges Party, and its Regulatory Forces.

Since 1937, the Phalanges Party, or Kataeb Party, had a standing militia, the Kataeb Regulatory Forces (KRF). In light of growing domestic concerns as well as external powers seeing an interest in finding sides in a coming war to support, its armed forces were quickly swelling. At the height of the civil war, it could count Israel Defense Forces (IDF) and the United States of America as its backers.

Georg was never clear to me what his father’s role had been in the militia. What he was clear on was that in September 1981, his father disappeared. Georg, 16 years old, was now the head of the household and left with a heavy heart and few prospects. The KRF offered a small amount of money to the family, but not enough to actually survive on. The word given, by friends inside the party, was that Jean had been abducted and killed by the PLO-supportive and Syrian-affiliated militia group Lebanese National Movement (LNM).

With this in mind, Georg squared his shoulders and joined his father’s friends in the KRF. While the KRF was one of the better prepared and equipped militias active in the war, Georg only received a piffling amount of training. Instead, a great deal of importance was put on numbers, choosing the scene of the fight, and luck. Georg was essentially told that he would find what had to be done to survive or die trying.

Soon after joining, Georg found himself facing off in a battle against a Shi’a militia group, in the middle of a Beirut street. Georg quickly learned that on the mean streets of a sectarian war, the only friend one has is the one that is firing in the same direction as you, and has cigarettes to offer. Everyone else is the enemy. Soon these rules of engagement gave way to the unbridled truth of the disorganized battlefield; “Luck rules supreme, and avoid the old man named Murphy.“

Over strong Turkish coffee, the kind that leaves a layer on your teeth and tongue, Georg and I would compare notes on irregular warfare, and how it impacts those that experience it in their formative years. Georg, ever the humble one, attributed his survival to the will of God, and to Luck. I, on the other hand, credited sufficient training, and, admittedly, luck as well.

“No,” Georg said, “Luck plays a greater role in the outcome of the individual’s survival than training. I saw Israelis come to Lebanon; they had great training, but they still ran off with their tails missing. The Shi’a made sure of that; an army of peasants.”

“Certainly, “ I responded, “but you have to keep in mind that Israel was never geared for that kind of warfare – they simply did not realize what they were getting themselves into. Their training was not smart enough for Lebanon,” I said with what I hoped to be a disarming smile.

The joke did not seem to take with Georg.

“No one can ever be prepared for what war is like — much less war here in Lebanon. They never stood a chance. They thought that it would be like before, with tanks and artillery. Artillery was part of it, but tanks just made for targets. After all, all your smart training doesn’t stand a chance against my dumb luck. All it takes is one bullet, one bullet of good and bad luck.”

“Train smart, but do everything possible to be lucky?” I asked, “Just be lucky.” Georg responded.

From Beirut

November 22nd – Lebanese Independence Day – is the day that Prime Minister Saad Hariri returned. At that point, he had been missing from the Lebanese political scene since November 3rd. It was on November 3rd that he received a phone call from the Saudi Royal Court inviting him to a meeting with King Salman of Saudi Arabia — a meeting that could not be refused.

Hariri, a Sunni politician, owes a large part of his political position and good economic fortunes to the Saudis. With this in mind, he immediately flew to Riyadh, for an audience with the King. A day after arriving, he resigned from his publicly elected office in a broadcast made over the Saudi state-run television channel Saudi One.

In his announcement, Hariri said that he had been informed of an assassination plot against him, and accused Saudi Arabia’s arch-foe, Iran, and its Lebanese ally Hezbollah, of disrupting the Middle East. In light of this, he saw no other recourse than to resign from office.

The abrupt announcement of resignation stunned and shocked the Lebanese public. The President of Lebanon, Michel Aoun, refused the Prime Minister’s resignation, stating that such a thing can only be done in person. Quickly the rumor began spreading that Hariri was being held hostage and that the Saudis had forced him to resign. A public outcry of support quickly emerged.

With little information beyond the TV broadcast, the traditional rumor mill soon began turning. Was the Lebanese prime minister being held captive, hostage even, by the Saudi royal house? Soon, even established and somber parties joined the chorus of concern. The situation reached its pinnacle when Lebanese President Aoun himself went out and voiced concern over Hariri’s situation. Regional analysts were quick to point out that if Hariri was part of a Saudi anti-Iranian push, using Lebanon as its launchpad, then it would behoove Iran to establish undermining rumors such as this. Considering that President Aoun has strong ties to the Shi’a militia group and proxy of Iran Hezbollah, this take on the situation could be further considered.

In Lebanon, the dynamic between the President’s and Prime Minister’s offices is a fragile one. It stems from the political configuration that the French Mandate of Syria and Lebanon established in 1920 to ensure their own influence and the preservation of Christians in power positions. Thus, the Lebanese government is set up this way ostensibly as a sectarian power-sharing agreement.

Upon returning to Lebanon, Hariri’s convoy proceeded straight from the airport to the grave of Hariri’s father, Rafic Hariri. Security had already cleared the area with a large security perimeter having been established ahead of time. Upon exiting his vehicle in the convoy, Hariri entered to the inner chamber of the memorial, where a large photograph of his father hangs. In front of the photograph, Hariri stood in silent contemplation for what eyewitnesses describe as a solid 10 minutes.

His father, the former Prime Minister, had been killed February 14, 2005, by a car bomb in central Beirut. Syria was initially accused of the assassination, which led to the withdrawal of Syrian troops from Lebanon. Nine years later, the United Nations released a series of reports that did, in fact, implicate the Syrian government in the attack. Ultimately though, it appears that operators from Hezbollah, the Iranian proxy militia, orchestrated the murder and paid the family of a young, unemployed male to carry out the suicide attack.

Thus, the death of Rafic Hariri set in motion events that toppled the Lebanese pro-Syrian government and drove Syrian forces out of the country. A commonly-held belief today is that the assassination was carried out on behalf of the Syrian government using assets and resources from both Hezbollah as well as the Syrian Military Intelligence Directorate.

Not only would Lebanon wake up in a few hours to the news that their Prime Minister had returned, but also to their 74th Independence Day.

She hugs everyone; to her, there is nothing to fear,” her grandfather said to me.

I will die before that is allowed to change.”

The Smile of the Innocent

April 2006. The hustle and bustle of the open air market enclave of Corniche el Nahr could overwhelm one’s senses. Summer was yet to arrive in full force, but the warm winds of late spring were just right. The entirety of north Beirut’s population appeared to be out, and Georg and I were moving through the crowds. I found myself in this vortex of people for a reason.

Georg was a man on a mission, searching for something in the throng of people before him. Swiftly moving between the microscopic gaps between people and stalls, he gracefully weaved in and out of sight, his gray suit, and short-cropped hair blending in perfectly whenever he so wanted. One minute he would be next to me, the next he’d be five stalls down. It was obvious that he was utilizing every ounce of experience and focus that only a man that had hunted for snipers during asymmetric warfare in urban terrain could muster.

Georg abruptly stopped, as if he had found a whiff of something in the air. The glimmer in his eyes told me that he had found what he was looking for: “Ah! Perfect,” Georg said as he reached out to grab the box off of the table. It contained a medium-sized stuffed cotton doll. It was Georg’s granddaughter’s five-year birthday and he had just found the first of many gifts.

“It is my duty to spoil the girl,” he said with a wolf grin that only a proud grandparent could summon. With the grin firmly in place, he turned towards the stall keeper and began the dance of haggling over pennies. Throughout this display of combat, which lasted for less time than it took to finish off my paper cup of tea with condensed milk and mint, his grin never wavered. It merely morphed from the grin of a wolf pleased to have found its prey, to that of a wolf hunting its prey. By the end, a deal was struck, and a few crumpled up dollar bills traded hands.

With Georg’s mission of the day successfully accomplished, it was time for more coffee, accompanied by French pastries. As we made the brisk walk to a nearby French bistro that had, what Georg deemed acceptable, the right assortment of pastries and coffee, he clutched the plastic bag containing the doll close to his chest. Precious cargo indeed. I would have pitied anyone foolish enough to attempt to come between Georg and his granddaughter’s gift.

The social scene in Beirut is café-oriented, like most of the Middle East. The main difference is the slight West European flavor that Beirut enjoys in its cafes and coffee. You could easily fool yourself into thinking that you are sitting in a bistro in Madrid or Paris while sipping your cappuccino in downtown Beirut. But unlike Spain or France, in Beirut, there’s no dressing down to go out in the evening.

The sidewalks of central Beirut are much more similar to the catwalk of a fashion show than that of a sidewalk in Europe, filled at various hours of the day with people trying to dress up and be as fashionable as possible. As such, it is important to hold certain key strategic places in a frequent rotation if you wish to meet people from certain social cliques. Georg had early on helped me create a map of where to meet the young up and coming people from the various political parties, causes and foreign dignitaries alike. These places became key strategic locations when dealing with people from central Beirut, where it can quickly become important to be seen in the right places. To say that I was maladjusted, fashionably speaking, for the Beiruti scene will always be an understatement, but I managed after awhile.

After a suitable amount of time relaxing over coffee and flaky pastries, while quietly chatting about the value of family, Georg invited me to come by and see the jewel of his heart, his granddaughter. Georg’s family, including his mother and daughter, lived not far away near the Escalier de l’Art stairs, in Achrafieh, where they had a house. The area had long been a Christian enclave and been known for its artistic communities. During the Civil War, it had lost some of its artistic and bohemian luster and instead became part of the Muslim-Christian frontline. In recent years through the open air art exhibits had returned, yet again making it a tourist destination.

His family had lived in the apartment building in some form since the 1920s, only briefly leaving it during the height of the civil war when their family had been targeted by certain militia elements. The French-colonial inspired, ornate six-story house, with a wrap-around balcony and a rooftop to use for meetings, was a beauty to behold even if it was in some disrepair by this point. The ownership status of the house had remained in some dispute, with Georg’s family insisting that it owned the top floors. The family that had the lower stories lived in Italy at the time but had entrusted Georg with keeping an eye on the house as a whole.

Georg’s daughter had met her husband, a Jordanian-American with kind eyes and a quiet voice, while they were both studying dentistry in the States. They had married a few years later. Now, they were dividing their time between Chicago, Amman, and Beirut. During the spring and autumn months, it was a given that they would be in Beirut because Georg would never have accepted anything short of spending at least half a year with the entirety of his family under one roof. He often spoke of his son-in-law fondly, remarking of how kind the man was towards his daughter. The man held to the notion that children should be seen, but not heard, something that Georg sympathized with but did everything he could to undermine at every step possible. Spoiling the child rotten had seemingly become Georg’s true mission in life, and it was generally agreed on that he was a little bit too good at it.

The girl was named Diana, after the British princess whom the mother adored. She had chestnut brown hair, dark eyes, and always a genuine smile on her face. Upon entering the apartment, she quickly ran up to her grandfather and hugged him dearly. The two would spend as much time as possible together, and she would often ride on her grandfather’s shoulders as they strode around the Gemmayzeh neighborhood art shows. Georg loved classical music, whereas Diana did less so. But she tolerated her grandfather’s insistence on bringing her to outdoor concerts, where she could see all and hear even more whilst perched on his shoulders. She knew that it made him happy, and he knew that to keep her happy he would have to sneak her candy every so often.

She looked at me and then asked her grandfather if she could give the strange stranger a hug, too — a proposition that no brute could refuse. I had met her a few times before, but to her, I was always “the strange stranger”, which is how her grandfather had first introduced me to her. “She hugs everyone; to her, there is nothing to fear,” her grandfather said to me. “I will die before that is allowed to change.”

Soon in a theater near you

November 22, 2017. The celebrations were in full swing. President Aoun stood proudly looking across the gathering crowds. Next to the President stood the recently returned wayward Prime Minister, Saad Hariri. It was November 22nd, and the Lebanese people were celebrating their independence from the French empire, and the creation of the independent state of Lebanon. They were also celebrating the return of their Prime Minister.

Merely an hour earlier, the Prime Minister and the President had met in private to discuss recent events: the controversial resignation of Saad Hariri. As a result of the dialog, the actual content of which only the participants know, Hariri agreed to stay on as Prime Minister for now.

After the meeting, Hariri tweeted, “Our beloved nation requires at this precise moment in its life exceptional effort from everyone, in order to protect it as it faces danger and challenges. These efforts start with an adherence to a policy of neutrality with regards to everything that hurts internal stability and our brotherly relations with the Arabs.” By this announcement, Hariri had eased the most recent Lebanese political crisis.

إن وطننا الحبيب يحتاج في هذه المرحلة الدقيقة من حياتنا الوطنية إلى جهود استثنائية من الجميع لتحصينه في مواجهة المخاطر والتحديات. وفي مقدمة هذه الجهود، وجوب الالتزام بسياسة النأي بالنفس عن كل ما يسيء إلى الاستقرار الداخلي والعلاقات الأخوية مع الأشقاء العرب. #بعبدا #عيد_الاستقلال

— Saad Hariri (@saadhariri) November 22, 2017

But Hariri’s return did not just equal the joyous end of a crisis. His return also cast dark shadows of a future most unclear, and most dangerous.

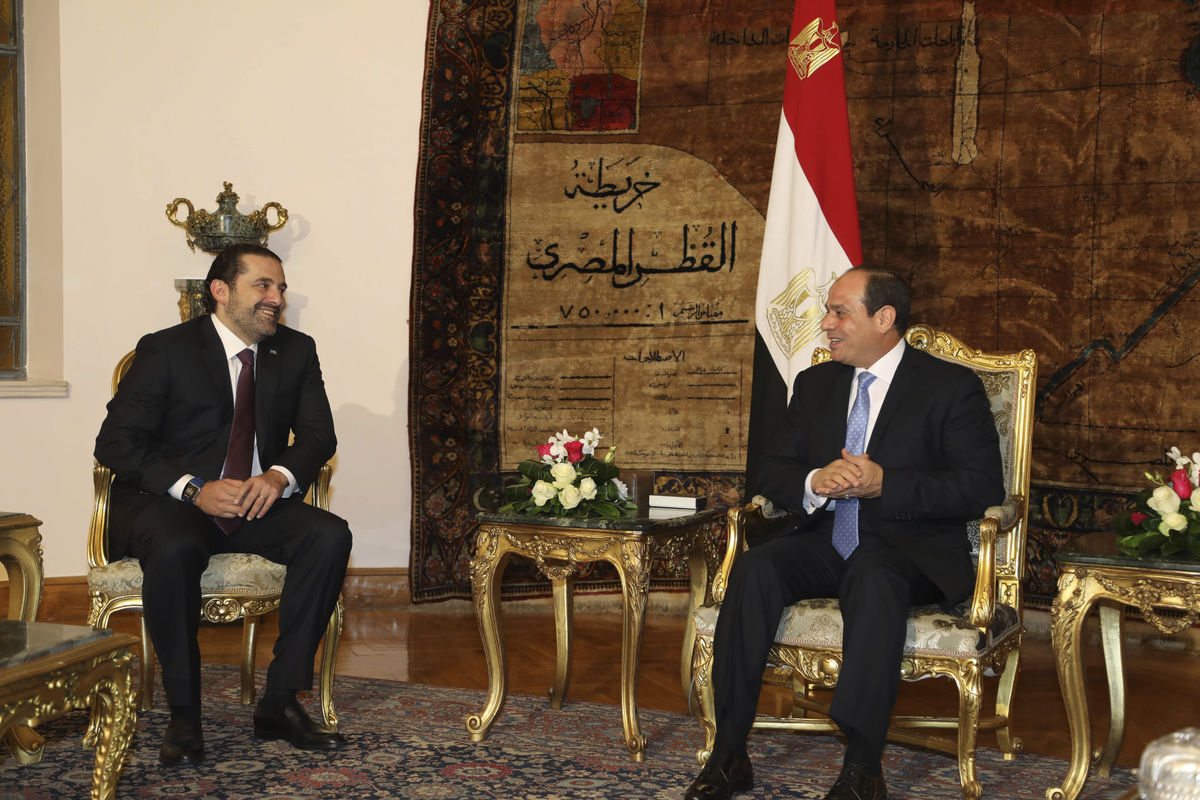

When Hariri departed Saudi Arabia on November 18th, he did not adhere to his public statements to fly straight home. Instead he flew to Paris, to meet with French President Emmanuel Macron. The two held a private meeting behind closed doors, and a sequence of meetings thereafter were held in much the same vein.

On November 21st, he traveled to Cairo. Once the customary and traditional shaking of hands between Egyptian President el-Sisi and Hariri were completed, Hariri immediately met with members of the Egyptian military intelligence agencies. Also present during these closed-door meetings was the top Egyptian military leadership.

Privileged sources close to Lima Charlie News say that among the topics discussed in both France and Egypt was that of Iran, and the future of the Middle East. With the Prime Minister of Lebanon acting the role of envoy on behalf of the Saudi royal house, especially the newly ascended crown prince, a message was brought forward: war is coming.

Hariri had become the envoy of war.

Almost immediately after the last meeting with top echelon military officials in Egypt, Hariri boarded his private plane and began the journey home to Lebanon, and to the future first battlefield of the war against Iran.

Upon arriving, Hariri placed a series of demands through intermediaries to Iran’s premier representative in Lebanon, Hezbollah. While his official position is one of neutrality, it is also fiercely unaccepting of Hezbollah’s position. According to a statement on November 22nd, he opposed anything that will “affect our Arab Brothers or target the security and stability of their countries.”

To Jerusalem; a jump, a skip, and a fall

August, 2006. The sun hung over our heads, like a participation medal for showing up. The summer had hit hard this year, baking everything under its glow. This included the three of us, traveling in a beat-up Toyota Corolla with a mere facsimile of a working fan for cooling, on our way to a fact finding mission. To observe; to analyze, not advocate.

We headed down a dirt road in the general direction of the small strip of disputed land called Shebaa Farms in southern Lebanon. The area was largely controlled by Hezbollah, with the Israelis making haphazard claims of the same. Both sides regularly either send fighters or rockets towards each other.

During autumn and spring, the Shebaa Farm area is an idyllic landscape of green, rocky hills, and fertile land. But at the height of summer, it quickly becomes an oven. As you ride along one of the many back roads towards Mount Hermon, you can easily be lulled into a near trancelike state of contemplation. The country has a mournful, yet beautiful soul. But in the Middle East one quickly learns this: where there is beauty, there is violence.

A mere jump across the mountainous ridges from the Lebanese military positions lay Syria, and its Golan Heights. A skip further, and you find yourself inside Israel. In an ideal world, the area would be a premier trading hub, maybe a freeport of sorts. But in this world, it is a frontline in the war between states and non-state agents alike.

The rocky hills keep many secrets. Not only is the area brimming with rivaling militia groups, it is also one of the foremost smuggling routes for fighters and weaponry. Sunni, Shi’a and Christian militias often find themselves running into one another, with reliably volatile results. It is easy to pass, blithely unaware, through one of the many frontlines in a place like this. One is quickly reminded of this reality driving down the rocky dirt roads. Take a turn and you can come face to face with (if your luck is favorable), a Lebanese Army patrol.

The band was making good time. We had an appointment to make. We were set to link up with Georg at midday, and have tea with key members from Hezbollah at 1300 hours. Another day in the office.

But by the time we got to the predesignated rendezvous point for Georg, there was nothing but the birds in the sky, and rubble on the ground to find. With the cell phone systems in the area being intercepted on good days, and jammed on most other days, we were out of luck. Georg had not turned up, which changed things. While I already had the contact numbers for the people in Beirut that had arranged the meeting with Hezbollah, we were under strict instructions to not proceed unless everything went according to plan. The security situation in the area was tense. Just a few days earlier an Israeli paratrooper had been shot and killed while on guard duty. It was with this in mind that the field researcher I was accompanying made the executive decision that a late lunch in Beirut was a marvelous idea.

A few days after arriving back in Beirut, I reached out to Georg through the regular channels. This was before the smartphone and online social network revolution had taken hold. This meant that not “everyone and their grandmother” carried a smartphone, or was found on Facebook. Nor did they chat their existence away on one of the many instant messenger apps we have today. Truly it’s a marvel that we all survived to tell the tale of this dark age. Through an intermediary, I found out where Georg was:

At the cemetery. The funeral had been two days ago. I would not have attended at any rate.

Hours before my merry band of Oakley-wearing Jason Bourne wannabes had begun to make its way towards the dirt roads, Georg’s luck had apparently run out. Like many in Beirut, Georg favored holding meetings on rooftops, of which he had access to many, spread out across the city. He had apparently been “suicided” off a rooftop in south Beirut. From that height, the only thing that could survive the fall was a corpse. The fall had turned parts of his body into jelly with bits in it. He had been a fairly decent man towards us. Such “suicides” are not uncommon in the Middle East — especially not in the back alley battlefields where the major regional players duke it out: Israel, Syria, Saudi Arabia and Iran. His mother would never come to terms with the notion that her son’s death was written up as a suicide. But then, few mothers would. His family lives in the United States now.

A few days after Georg’s funeral, on July 12th at 0905 local time, Hezbollah initiated Operation Truthful Promise by launching a barrage of rockets and mortars against an Israeli patrol near the border area, not far from where my team had been set to meet with Georg and members from Hezbollah. The attack resulted in 8 IDF soldiers killed and 2 others abducted. Israel quickly responded, carrying out a series of air and ground attacks which devastated the frail Lebanese economy and infrastructure.

The Coming Uncivil War

According to exclusive, highly-placed Lima Charlie News privileged sources, Hariri will soon renew his demands on Hezbollah. This time the demands will be made in a more public setting. The original set of demands were delivered to Hezbollah and its masters in Tehran through affiliated intermediaries. If Hariri’s demands are not met, his first step is said to be his resignation again, causing yet another political crisis in Lebanon.

The first of Hariri’s demands was that Hezbollah must unilaterally disarm its forces in Lebanon and the region. This is extremely unlikely to happen. The commander of Iran’s Revolutionary Guards, Mohammed Ali Jafari, has already stated that disarmament of Hezbollah is out of the question.

Second, Hezbollah must leave its enclaves in Southern Lebanon and must abandon captured areas of Syria. Hezbollah troops, in their continuing role as Iran’s proxy, have been in combat to support Assad’s Syrian government since 2012. Iran has provided logistical and financial support, as well as active Iranian combat troops, to the Assad regime. Iran sees Assad’s government as crucial to its own interests in the Middle East, as Syria has remained the sole staunch ally of Iran since the 1979 Iranian Islamic Revolution. Assad’s Shi’a/Alawite party is also viewed by Iran as a way to slow or halt the advancement of Saudi Arabian and US influence in the region.

Mohammed Ali Jafari also stated that Iran’s Revolutionary Guards are prepared to rebuild Syria and enforce a ceasefire there. Iranian and Hezbollah elements hold the eastern corridor of Syria, bordering with Lebanon, marking a proximity too close to Lebanon for comfort. As the final demand by Hariri, Iran must cease its political operations through Hezbollah in Lebanon.

It is extremely unlikely that Hezbollah and Iran will agree to any of these terms, thus, Hariri will have to resign. His demands and the power vacuum left by his departure could be the excuse for Saudi Arabia to ignite the match that would spark a new Lebanese civil war. Hariri’s time in Saudi Arabia, combined with his trips to Paris and Cairo, appear to be part of a larger strategy designed to gain support for a hardline stance against Iran and Hezbollah. His upcoming demands are the next step in this overall strategy.

Should a new civil war occur, is Israel likely to enter, in order to protect its security? Saudi Arabia and the US will, as always, support their proxies against Hezbollah and Iran. The US has a vested interest in a war in Lebanon that will diminish the influence of Islam — both Shi’a and Sunni — by allowing them to “fight each other out.” This diminishing of influence extends to Saudi Arabia as well.

With the whole region becoming destabilized, the US may directly enter the war, followed by, possibly, Russia. This has the makings of the start of a potential World War III.

John Sjoholm and Brian Jones, Lima Charlie News

John Sjoholm is Lima Charlie’s Middle East Bureau Chief, managing editor, and founder of the consulting firm Erudite Group. A seasoned expert on Middle East and North Africa matters, he has a background in security contracting and has served as a geopolitical advisor to regional leaders. He was educated in religion and languages in Sana’a, Yemen, and Cairo, Egypt, and has lived in the region since 2005, contributing to numerous Western-supported stabilisation projects. He currently resides in Jordan. Follow John on Twitter @JohnSjoholmLC

Brian Jones is a co-founder of the consulting organization Erudite Group, entrepreneur, writer, tactical and wilderness skills instructor, and personal security consultant who has worked in many regions of the world. He has trained and worked with many agencies, including the Boston, Massachusetts Police Department, and the US Army Mountain Warfare School. He currently heads a small boutique security firm that consults for select celebrity and executive clients.

Lima Charlie provides global news, featuring insight & analysis by military veterans and intelligence professionals Worldwide.

For up-to-date news, please follow us on twitter at @LimaCharlieNews

In case you missed it:

](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/Hezbollah-Vehicles-Weapon-Transport-480x384.jpg)

![Image En Marche! France’s economy stands at a crossroads and for Macron, failure is not an option [Lima Charlie News]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/En-Marché-France’s-economy-stands-at-a-crossroads-and-for-Macron-failure-is-not-an-option-480x384.png)

![Image Macron ignores domestic pressure, attempts take the lead of Western diplomacy in Syria [Lima Charlie News][Image: Reuters / Stephane Mahe](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/2018_04_08_43616_1523165065._large-1-480x384.jpg)

![Blossoming Russo-Turkish alliance leaves U.S., NATO behind [Lima Charlie News]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/Russia-Turkey-alliance-leaves-U.S.-NATO-behind-480x384.png)

](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/Hezbollah-Vehicles-Weapon-Transport-150x100.jpg)

![Image En Marche! France’s economy stands at a crossroads and for Macron, failure is not an option [Lima Charlie News]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/En-Marché-France’s-economy-stands-at-a-crossroads-and-for-Macron-failure-is-not-an-option-150x100.png)