Russia is not resting on its laurels. With Syria’s central government readying to dismantle the last remainders of opposition in Daraa, Russia is seeking to re-legitimise the al Assad regime. To accomplish this, Russia and Syria are capitalizing on a refugee crisis, a lack of regional organisation and an unwillingness to lead Syrian restoration efforts.

There seems to be little doubt that in the coming days Bashar al Assad’s government will capture the last remaining opposition-held enclaves in the city of Daraa. Daraa is, in many regards, the birthplace of the current rendition of the Syrian opposition.

Spray paint, steel and the fall of Daraa

It was here, in 2011 that a handful of young teenagers spray painted on a few walls popular Arab Spring-sayings along with the message “Your turn, Doctor” (Ejak el door ya Doctor). “Doctor” refers to President Assad’s training as an ophthalmologist. The teenagers would be arrested and tortured by Syrian intelligence services.

The families of the teenagers called upon the local tribes to protest, to show solidarity. Soon they were joined by their neighbours and communities. It was from this that the Syrian Civil War began, not from the barrel of a rebel AK47, but with spray paint on a school wall. A message that a 14-year-old had seen on TV.

Within the first four years of the war the central Damascus government had lost control over more than 80 percent of the country. This despite the backing of Russia, Iran and their Lebanese militia-proxy group Hezbollah.

Soon the diverse interests within the opposition, combined with the influx of foreign fighters of more extreme religious viewpoints, began taking its toll. As a result, despite having a unifying enemy, infighting amongst the anti-government groups soon made it impossible to succeed.

The war has now, by its seventh year claimed the lives of more than 500,000, and displaced well over 12,000,000 Syrians.

The battle for East Ghouta would quickly become one of the bloodiest battles for all sides involved.

As is the norm in battles of this kind, the civilian population remains caught in the middle, and is doomed to pay the dearest price of all. To ensure its victory, the SAA would deploy chemical agents, and commence one of the heaviest artillery and aerial bombardments seen since the U.S. military and intelligence operations in Laos, or the Western Front during World War 1.

The fall of Eastern Ghouta would come to represent the civilian collateral and savagery that the SAA, and its commanding government, would be willing to exude over both those that stand near and those that oppose the government. After having secured East Ghouta, Assad exclaimed that Daraa was next.

![Image [Drone footage of Russian, Syrian airstrikes in Daraa]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/Daraa-airstrikes.png)

Nor will it spell the end of the embers of opposition that brew under the desert surface.

The surge of violence throughout Syria will continue for the foreseeable future. But it will take increasingly, and disturbingly less organised forms. At least two generations of Syrians must pass in relative peace to overcome the culture of violence, sectarian conflicts, and destabilising humanitarian plights that have solidified in the recent decade.

That development can only happen under ideal circumstances. It will not just require an intense series of reconstruction projects. To rebuild Syria, its now shattered society must be restored. This can only happen if the region, which remains fragmented, along with the international community, which remains confused, can manage to join forces with humanitarian groups to give Syrians a fighting chance. That likelihood is both an optimistic and simplistic outlook of what is to come in the immediate and distant future of Syria.

No regional player, except Assad himself, will likely be proven eager to carry the burden of coordinating such an effort. And if one does emerge, he will probably be fashionably late. It takes no Metternich or Machiavellian genius to implement skewed agendas under the guise of the overall good at this point.

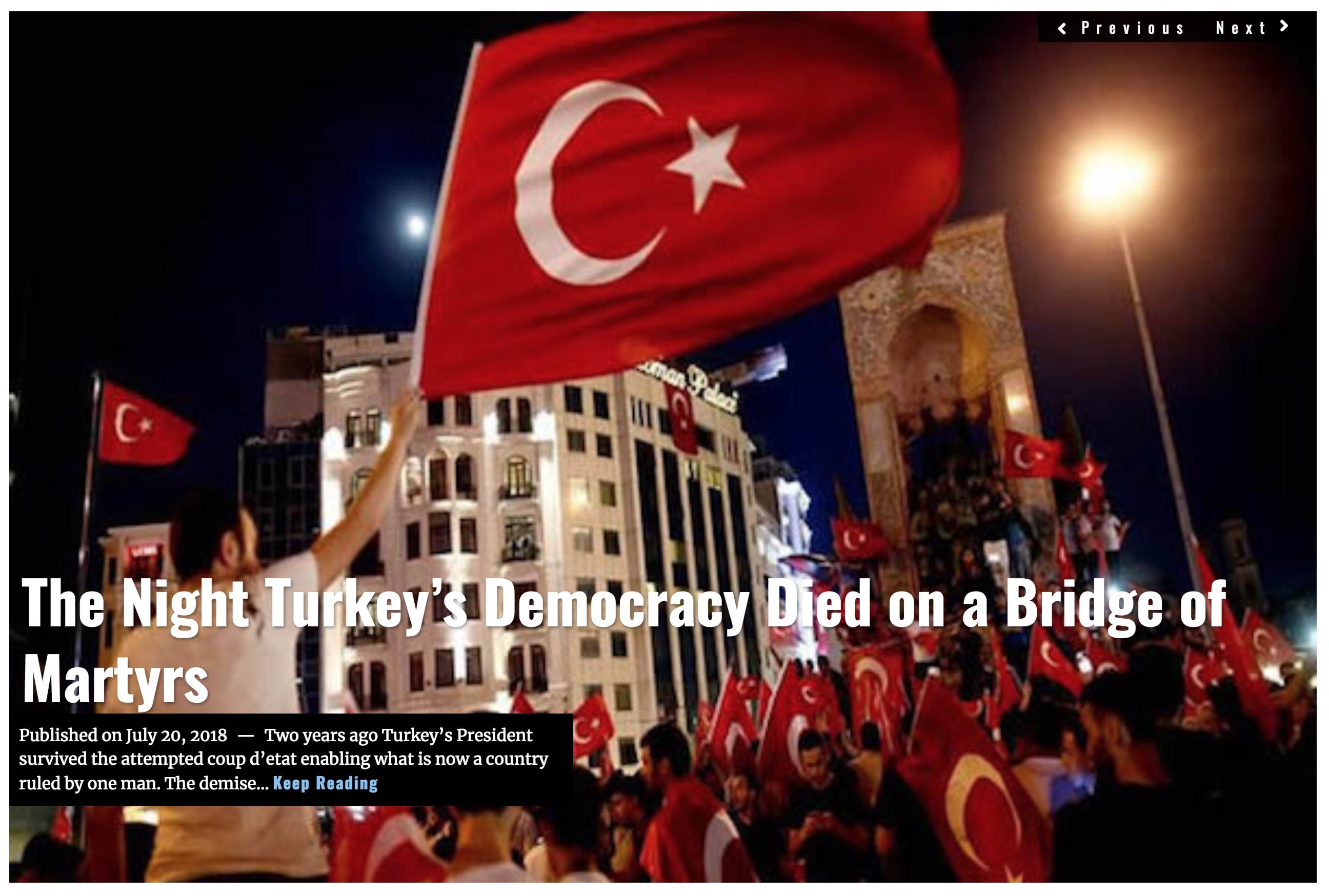

Refugees GO Home: The Legitimisation of Assad

Russia was, predictably, the first to attempt to shape the future in Syria.

Pre-empting the Saudis and Western powers, Russia deployed a contingent of emissaries to Lebanon, Turkey and Jordan with a proposal seeking to enable, and ultimately force a return of Syrian refugees to Syria. Announced last week, another aspect of the Russian proposal was that a joint regional group would be set up to finance the restoration of infrastructure. The group would be led by the Syrian government.

The populist notion of a refugee exodus is a powerful one, and could quickly gain traction across the region. The vast influx of Syrian refugees into neighbouring states has been exacting a punishing strain on regional economies, especially the Jordanian one, as well as communities.

According to official figures, Jordan alone is home to more than 1.4 million Syrian refugees. More than 85 percent live in host communities, i.e. government supported or independently supported communities outside of refugee camps. 8,037 Syrian refugees returned voluntarily from Jordan to southern Syria in 2017, after the Syrian government had managed to create a modicum of stability in certain enclaves. The growing number of refugees in Jordan is a long-standing, and unpopular problem, and the government has said that it can not take in more.

While the exodus idea is, on the surface, a popular one, it doesn’t stand up to closer scrutiny. If the borders had been opened and a Syrian refugee exodus forced, those returning would have found themselves in the middle of a battlefield whose true outcome is yet to be decided. The human cost at this point would be devastating, compounded by the absence of functional civil law enforcement to protect people and property, and to prevent crime and civil disorder amid a crumbled societal infrastructure. Worse yet, many that fled have done so because of their outspokenness – easy pickings for al Assad intelligence services if forced to return to Syria.

In reality, for Assad and President Putin, the real value of opening the borders is the re-legitimisation of the Damascus government, and the normalisation of its regional status. By initiating a refugee exodus, local governments would have to acknowledge Assad’s status, while also acknowledging that he stabilised Syria. Such a decision by refugee host nations would, at this point in time, not be based on actual ground reality, but on financial strains and populist appeasement. Such a decision would essentially be anti-humanitarian and an invitation for chaos.

The Jordanian government responded to the Russian proposal on July 22nd by saying that there were no arrangements underway to enable an exodus of Syrian refugees to Syria. Lebanon and Turkey are yet to make any public statements in response to the proposal, but sources familiar with the matter indicate that neither responded in the positive.

Jordan also cited humanitarian as well as security concerns over opening the Daraa border crossing (also known as the Ramtha crossing), which was closed in 2013, or the Nasib border crossing (also known as the Jaber crossing) which has been closed since 2015.

“We will only open the borders when there are no serious threats left and until the safety of individuals can be secured,” said Minister of State for Media Affairs, Jumana Ghuaimat.

Thankfully, the Russian proposal has so far been resisted: not a single local government’s foreign or state ministry fell for it.

John Sjoholm, Lima Charlie News

[Edited by Anthony A. LoPresti]

John Sjoholm is Lima Charlie’s Middle East Bureau Chief, Managing Editor, and founder of the consulting firm Erudite Group. A seasoned expert on Middle East and North Africa matters, he has a background in security contracting and has served as a geopolitical advisor to regional leaders. He was educated in religion and languages in Sana’a, Yemen, and Cairo, Egypt, and has lived in the region since 2005, contributing to numerous Western-supported stabilisation projects. He currently resides in Jordan. Follow John on Twitter @JohnSjoholmLC

Lima Charlie provides global news, featuring insight & analysis by military veterans and service members Worldwide.

For up-to-date news, please follow us on twitter at @LimaCharlieNews

In case you missed it:

![Image A Russian proposal to the refugees of Syria [Lima Charlie News][Photo: Louisa Gouliamaki / AFP]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/A-Russian-proposal-to-the-refugees-of-Syria.jpg)

![Syria’s oil, gas and water - the Immiscible Solution to the War in Syria [Lima Charlie News][Photo: ANDREE KAISER / MCT]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/Syria’s-oil-gas-and-water-480x384.png)

![Image Leaving Syria - a misstep continues to haunt America's allies [Lima Charlie News][Photo: JOSHUA ROBERTS]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/Leaving-Syria-a-misstep-continues-to-haunt-Americas-allies-Lima-Charlie-News-480x384.png)

![Syria’s oil, gas and water - the Immiscible Solution to the War in Syria [Lima Charlie News][Photo: ANDREE KAISER / MCT]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/Syria’s-oil-gas-and-water-150x100.png)