Why should anyone outside of Croatia and the greater Balkans watch Netflix’s hit show “The Paper” other than entertainment value and loads of sex, violence, and titillating political and church scandals?

This month Reporters Without Borders (RSF), the international non-profit that advocates for freedom of information and freedom of the press, issued a statement condemning Croatia’s government for remaining “astonishingly silent” about police investigations into recent attacks on journalists.

“Reporters Without Borders … is disturbed by the Croatian government’s silence about a spate of hate messages and threats against journalists and calls on the authorities to publicly condemn these attacks in order to end the impunity enjoyed by those responsible.”

RSF consistently ranks Croatia 64th out of 180 countries in its press freedom ranking. (Notably America’s 2019 ranking fell to 48).

“Are the Croatian words ‘Smrt novinarima’ (‘Death to journalists’) going to become commonplace in Croatia?”, states the RSF report, following the appearance of threatening graffiti outside of several news organizations. The widespread intimidation of Croatia’s journalists has included labeling them as worms (“Novinari crvi”), death threats posted on social media, physical attacks, fines, arrests, frivolous lawsuits and political pressure.

Just this week, journalist Gordan Duhacek, who writes for the popular Croatian news website Index.hr, was arrested and fined for posting an “anti-police” message on Twitter.

Cited by arresting police, Duhacek allegedly violated a 1970s law that states, “whoever discredits or insults public authorities or officials while carrying out, or in connection with carrying out, their duties or their lawful orders, shall be punished by a fine equivalent … to 50 to 200 Deutschmarks or imprisonment for up to 30 days.” The RSF’s recent report notes that in Croatia insulting “the Republic, its emblem, its national hymn or flag” is punishable by up to three years in prison and that “humiliating” media content has been criminalised since 2013.

In a recent interview, Hrvoje Zovko, president of the Croatian Journalists Association (CJA/HND), said “In Croatia, it’s open season on journalists”.

Amid protests and condemnation over threats to media freedom, RSF has also reported that Croatia’s state run radio and television network, Hrvatska Radiotelevizija (HRT), is the target of government meddling and “is clearly under political pressure”. According to RSF, interest groups attempt to influence HRT’s editorial policies and interfere in its internal operations.

Yet, something very interesting has come out of HRT, content that is now available to almost half a billion viewers in almost 190 countries.

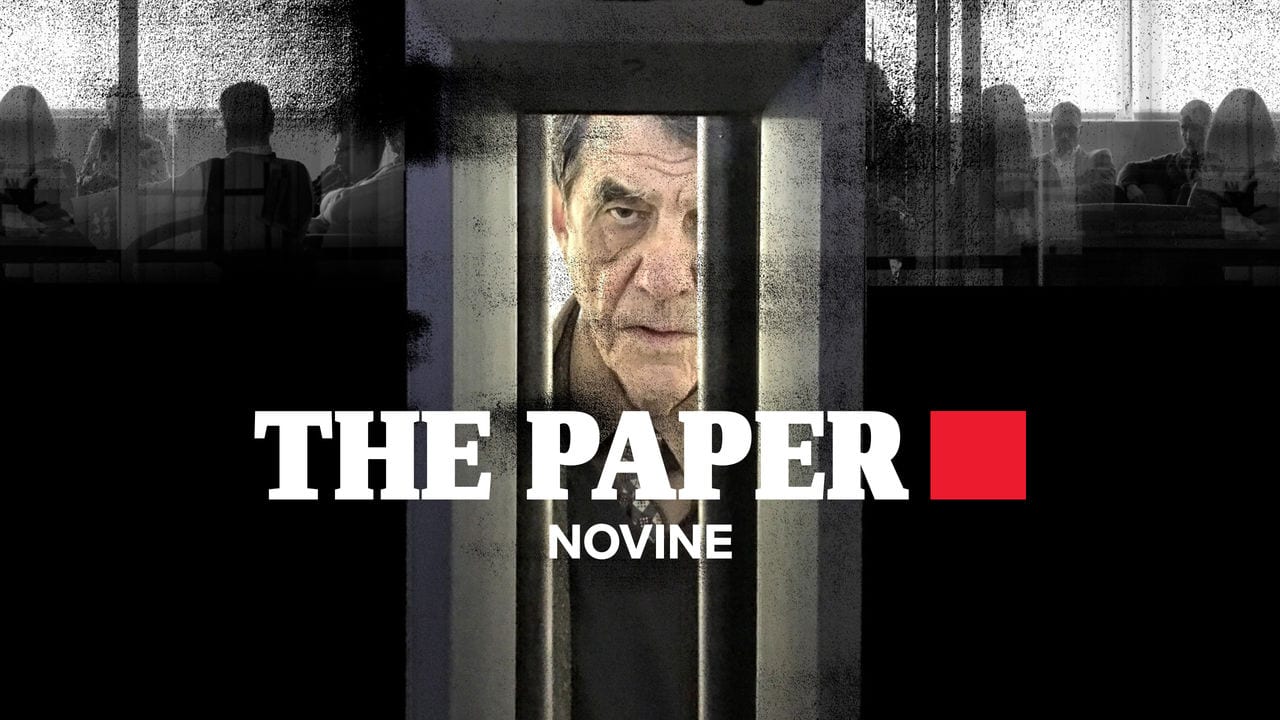

Commissioned in 2015, HRT provided 90 percent of the initial funding for the television drama “Novine”, a series focused around a fictional Croatian newspaper in the port city of Rijeka that IMDB describes as “The last independent newsroom in the country is taken over by a construction magnate for reasons that have nothing to do with love or respect for journalism.” “Novine” opened with construction tycoon Mario Kardum (played by Aleksandar Cvjetković), buying the newspaper after Novine journalists begin digging up dirt that linked Kardum to shady business dealings and a suspicious traffic accident where three people were killed. Kardum assumes total control of the newspaper.

Produced by Croatian production house Drugi Plan (Miodrag Sila and Nebojša Taraba), the series first premiered as part of Sarajevo Film Festival’s Avant Premieres before airing on HRT in 2016. Director Dalibor Matanić explained, “We wanted to explore and understand the events and social shifts that destroyed journalism in our country”. Written by renowned Croatian author and journalist Ivica Djikić, the Croatian-language series was lauded for its plot complexities, as well as its numerous sub-plots.

Mario Kardum: Aleksandar Cvjetković pic.twitter.com/JQ8cKwHjLS

— NovineTV (@NOVINE_TV) June 6, 2016

“Novine” became an instant hit. Before a second series could be produced, HRT announced in 2018 that American media juggernaut Netflix had bought the rights to “Novine” and would introduce it to the world, renamed “The Paper” for international release. After a successful second season, this June, Netflix announced that filming for the third season had begun.

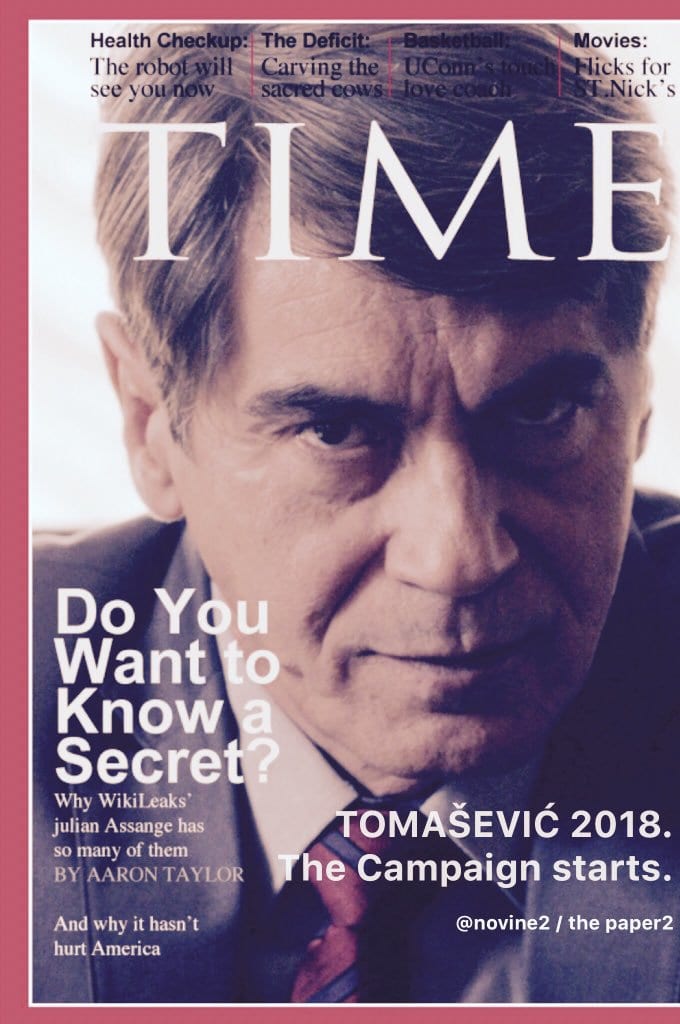

In “The Paper”, the nationalist, extreme-rightist, corrupt mayor of Rijeka is mounting his campaign for the presidency. This is the first instance of how the plot turns the actual situation on its head, as the city of Rijeka tends to be more liberal than much of the rest of the country and, as such, would be an unlikely place for the character “Mayor Tomašević” (played by Dragan Despot) to emerge. His political antagonist, Croatia’s President and head of the left-leaning Social Democratic Party, is obviously modeled after today’s real-world President Kolinda Grabar-Kitarović who is decidedly right-wing and nationalistic.

While American audiences often take a dim view to shows requiring subtitles, the series and its crew have been widely acclaimed for featuring excellent acting and production values. Rightfully so. It is quite apparent that Netflix has a binge-worthy hit on its hands.

And, yes, people actually do smoke and drink as much as it appears on screen. Whether or not they engage in as much sex is for someone else to judge.

So why should anyone outside of Croatia and the greater Balkans region watch “The Paper” other than entertainment value and loads of sex, violence, and titillating political and church scandals?

It is most noteworthy what the series says about freedom of expression in Croatia and the myriad problems facing a society still emerging from unresolved memories of World War Two, and fifty years of socialism under Josip Broz Tito. While this series should be of interest to a wide audience, it is especially of interest to diplomats and military men and women who have been engaged in the Balkans over the past two decades and may be wondering why their best efforts have achieved so little.

Anywhere money is the key to power and the primary motivator, the tale so well told in this series is common.

“The Paper” skewers each and every sacred cow in modern Croatian society. This makes a dramatic statement about freedom and openness in a country that only in the past decade has entered NATO and the European Union. By exposing the slimy underside of establishment politics, big business, the Catholic Church, organized crime and heroic accounts of the “Great Homeland War” of 1991-1995, this series scores a trifecta.

Still, all this might not be enough if it were merely exposing specifically Croatian fault lines. Rather, many of the problems revealed here permeate the entire region, other post-communist countries, and even Western Europe and the United States where the phrase “fake news” and accusations that the press is the “enemy of the people” have become commonplace.

The people of the states of the Former Yugoslavia will no doubt be able to recognize all of the sub plots as relevant to their own societies. Chief amongst those subplots are:

- The post-communist role played by ex-police/intelligence officers

- The rise of extreme nationalistic right-wing groups and policies to gain political advantage

- The financial and sexual misbehavior of religious figures and institutions

- The use of hardened war veterans for both ordinary crime and political assassination

- The power wielded by business/organized crime figures and their shifting alliances with public figures from all sides of the political spectrum

- The impunity from accountability so many politicians and oligarchs and their families enjoy because of money and connections

It is debatable whether Tito’s security services were relatively benign compared to their Stalinist counterparts in other countries, or just better at covering their tracks. Their operatives and successors continue to work and thrive, only reporting to new masters or working as free agents for personal profit. Can anyone doubt that they, or at least their imitators, have been involved in the many political assassinations and murders of journalists that have occurred since the break-up of Yugoslavia in the 1990s?

For example, were the killings in Sarajevo of the Bosniak police official, Nedzad Ugljen, and the Bosnian Croat politician, Jozo Leutar, just random incidents devoid of any influence from the top levels of government? What about the assassinations of Zeljko Raznatovic (aka Arkan) and several others in Belgrade before they could be arrested and, perhaps, testify against their superiors?

So many high-level eliminations and so few prosecutions are not a coincidence.

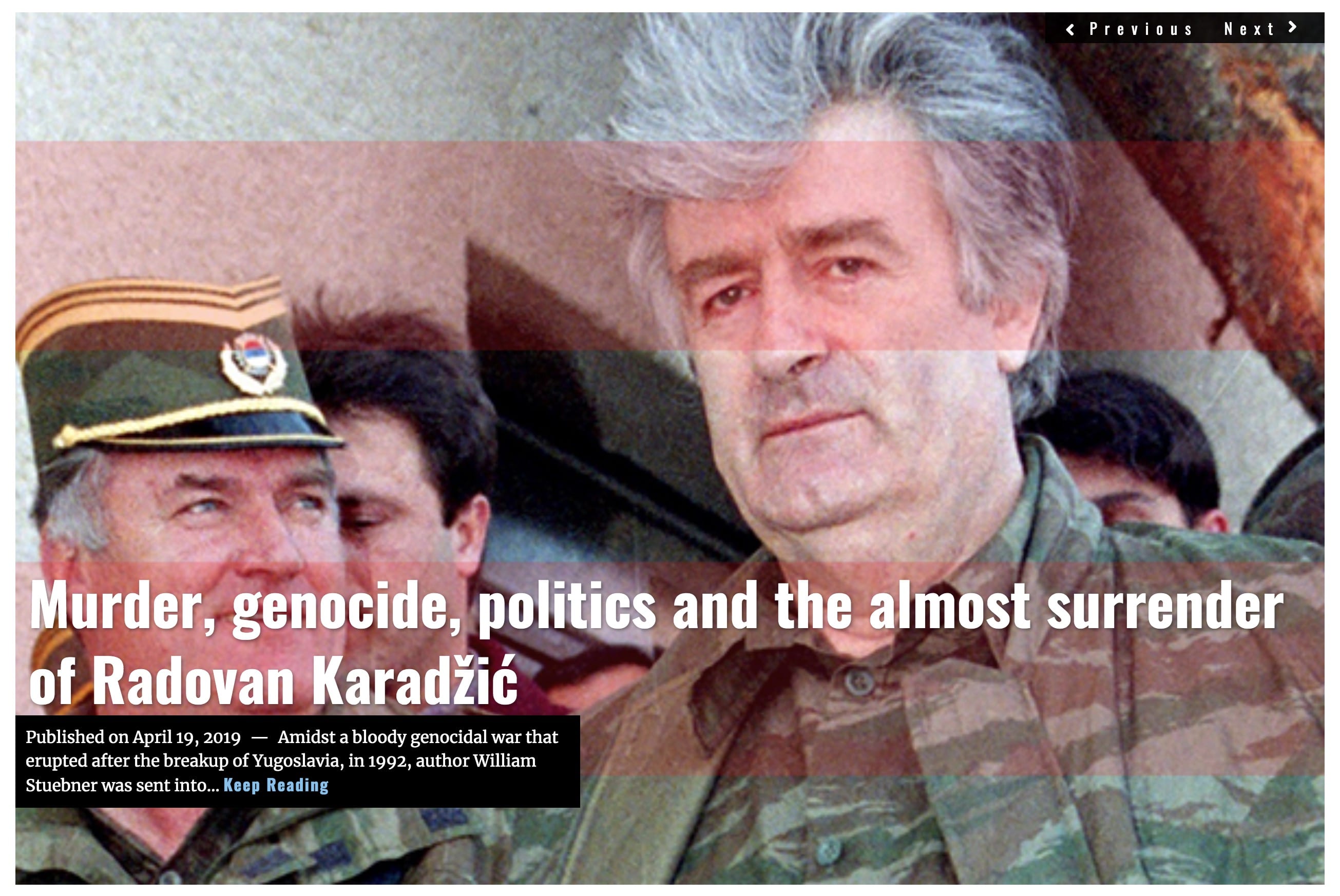

Take, for instance, the fact that the aforementioned Croatian President Kolinda can publicly mourn (rightfully) the mass executions of Croatians at Bleiburg at the end of World War II by Tito’s Partisans, yet ignore the many thousands of Serbs and others at Jasenovac, the Balkan Auschwitz? And what about Bosnian Serb President Milorad Dodik who denies the genocide at Srebrenica?

Of course, none of these kinds of activities are reserved only to the Balkans. Rather, the fomenting of hate, xenophobia and racism, especially on the Right, are just as common in Russia, Hungary, Austria, Italy, France, Myanmar, India, and, sadly, the United States of America.

As for corruption and sexual abuse by men and women of the cloth, this behavior is common in all faiths and in nearly every country. What makes “The Paper” storyline so unique in Croatia is that the Church has been sacrosanct and, indeed, Catholicism is elemental to the national identity of most Croatians. As shown in the series, Croatian politicians of every stripe compete for the blessings of the Church to boost their election chances. American readers may well recognize a similar pattern in their own country by substituting Catholic for Evangelical.

That some battle-hardened veterans find it convenient to sell the skills they have learned at great personal cost to the highest bidder should come as no surprise, especially in regions like the Balkans where good jobs are scarce. It was no accident that the notorious American security provider Blackwater found Serbia an especially good place to recruit triggermen. The contractor hired hundreds of Serbians with ground combat experience despite the fact that there was no ground combat in Serbia proper, unless one counts Kosovo, and even there close combat was rare. How convenient it was for both employer and employee to have a situation where one could be well-paid and operate in areas with no rule of law to get in the way.

If a veteran possessed no moral compass, or one where the needle always pointed in the direction of political authority and cold cash, it is naturally tempting for an unscrupulous politician to employ a skilled sniper or explosives expert to solve a problem quickly and easily. “The Paper” reveals a veteran sniper, who has already murdered an inconvenient police officer, seeking to assassinate the Prime Minister. This is not unlike a real-world incident in Montenegro where Serbs and Russians conspired to murder Prime Minister Djukanovic on the eve of his country’s accession to NATO membership.

Anywhere money is the key to power and the primary motivator, the tale so well told in this series is common.

While perhaps especially egregious in countries that arose out of totalitarianism, war and collective ownership, as we say in America, “politics makes strange bedfellows”, and we must wonder if our own system is any longer superior to that of the Balkan countries.

Finally, there are so many strong characters in “The Paper” that anyone not very familiar with the Balkans, post-Communist Eastern Europe, and the names of pre-war Yugoslavia (American pundit P. J. O’Rourke once referred to the Croatian conflict as the “war of the unspellables against the unpronounceables”) might find it useful to draw up a personalities list or chart just to keep up with who is screwing (both literally and figuratively) whom.

While it is difficult to pick out one character as being the lead, if it were possible to do so, probably “Dijana” (Branka Katic), a determined, courageous and promiscuous Serb investigative reporter who returned to Rijeka from Belgrade after the war would get my nod. She ties together more of the sub plots than anyone else.

Viewers, however, can form their own opinions from the large cast almost all of whom turn in masterful performances. My favorite characters include “Jure” (Drazen Mikulic), a tough war-veteran cop from Herzegovina who in many ways is a consummate professional, but who doesn’t shy away from setting off car bombs and beating suspects to a bloody, unrecognizable pulp; and “Blago” (Zdenko Jelcic), a scary career Yugoslav police/intelligence officer who transfers his loyalty first to Croatia and then to various political and business figures, while always maintaining a germ of humanity under his almost-psychotic facade.

[Spoiler alert]

Blago is ultimately betrayed and accused of murdering a neo-Nazi Croatian war hero at the behest of the government; an incident that informed viewers will see as a direct reference to the assassination of the real-life commander of the Croatian special forces, Blaz Kraljevic.

That the series can basically accuse the founding fathers of modern Croatia of this murder and get away with it is incredible. Like the fictional independent Rijeka newspaper, the series is making a stand on behalf of much needed journalistic integrity. Given everything “The Paper” reveals about societal undercurrents in Croatia, it should be no surprise to Western diplomats and soldiers who have served in the Balkans that so little lasting progress has been made.

That this series could even be produced demonstrates, however, that there is some cause for optimism. Perhaps the democratic and legal gates through which a country has to pass through to attain European Union membership really do have some beneficial effects.

But what about other countries like Serbia, Bosnia and Herzegovina and Kosovo who have not yet traversed the difficult path to EU membership and perhaps never will?

One cannot be blamed for being pessimistic, especially in Bosnia and Herzegovina where the complex Dayton Agreement-mandated political system has multiplied the opportunities for corruption, crime and officially-ordered murder. Sadly, this situation is exacerbated by almost complete legal impunity for the rich and well-connected. Until the day comes when the other former Yugoslav states can produce and broadcast programs like “The Paper” and hold everyone, including the highest political figures accountable to the rule of law, I remain gloomy about the possibility of societal progress.

Meanwhile, we should all recognize the warning signs of the same accountability problem in America.

Keep an eye out for the show’s third season currently in production. I am certain viewers will return for the sex and violence, and end up staying for the politics!

William Stuebner, for LIMA CHARLIE WORLD

[Edited / developed by John Sjoholm with additional edits by Anthony A. LoPresti] [Main Image: Courtesy HRT / Netflix / Drugi Plan ]

[Subscribe to our newsletter for free and be the first to get Lima Charlie World updates delivered right to your inbox.]

William Stuebner served in the United States Army for twenty years, first in the Infantry and then as a military intelligence officer. The last five years of his career revolved around the wars in Central America where he first led a special intelligence team and then worked as the El Salvador desk officer for the Department of Defense. He was also an assistant professor in the Social Sciences Department of the United States Military Academy where he taught politics and political philosophy.

Stuebner’s Balkans work began in May 1992, shortly after the commencement of hostilities in Bosnia and Herzegovina and continues to this day. His assignments included: Humanitarian Assistance Officer for the Department of Defense; Bosnian Field Representative for the Office of Foreign Disaster Assistance, United States Agency for International Development; Expert on Mission, Office of the Prosecutor, International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia (twice); Senior Deputy Head of Mission for Human Rights and Chief of Staff, Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe Mission to Bosnia and Herzegovina. He has also headed two Non-Governmental Organizations dealing with international criminal justice and peace building.

Lima Charlie World provides global news, featuring insight & analysis by military veterans, intelligence professionals and foreign policy experts Worldwide.

For up-to-date news, please follow us on twitter at @LimaCharlieNews

In case you missed it:

![A Trump war crime pardon dishonors us all [Lima Charlie News]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/A-Trump-war-crime-pardon-dishonors-us-all-Lima-Charlie-News-480x384.png)

![STRATEGIC OPTION | Syrian Endgame - The Hard Truth [Lima Charlie News][Photo: Bulent Kilic]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/STRATEGIC-OPTION-Syrian-Endgame-e1558501175322-480x384.png)

![A Trump war crime pardon dishonors us all [Lima Charlie News]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/A-Trump-war-crime-pardon-dishonors-us-all-Lima-Charlie-News-150x100.png)

Am enjoying the Netflix Series, Novine, but found it somewhat difficult to follow all the characters. So, thanks very much for

your very helpful recap of the show.