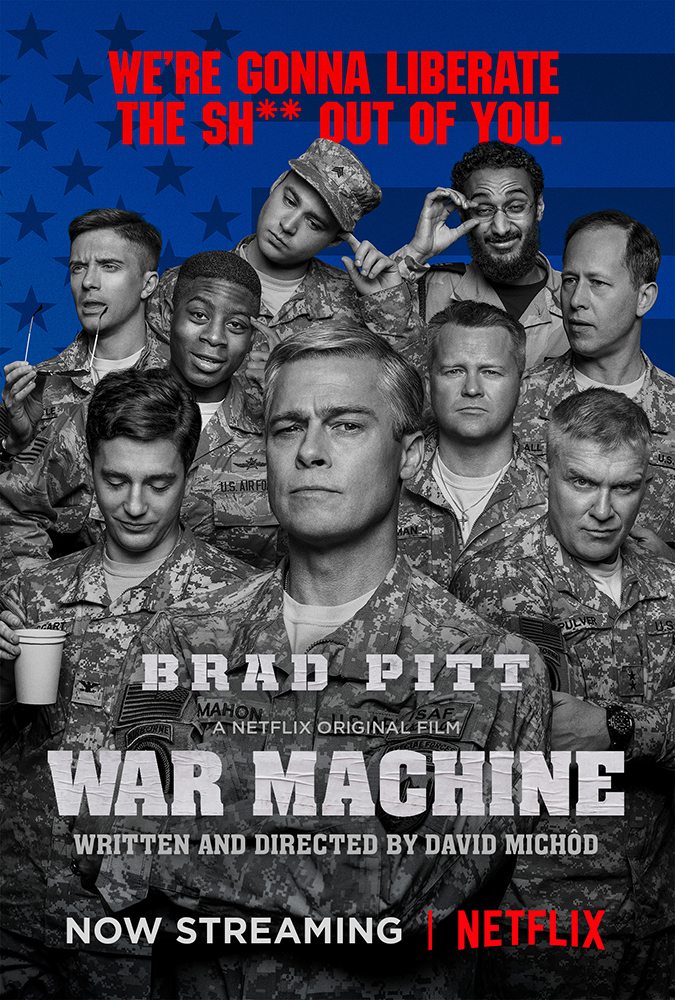

Netflix’s latest film “War Machine” stars Brad Pitt as General Glen McMahon. McMahon’s character is based on General Stanley McChrystal, who attempted to revitalize American involvement in Afghanistan between 2009 and 2010. It is virtually impossible to review the film without making some passing review of McChrystal and his ill-fated attempts. The problem is that David Michôd, the film’s director, was clearly lost in the source material, much like Pitt’s character is lost in Afghanistan.

The movie is loosely based on the book “The Operators” by Michael Hastings, which in turn came out of the Rolling Stone article “The Runaway General,” (full title: “The Operators: The Wild and Terrifying Inside Story of America’s War in Afghanistan”). Hastings died in a car accident in 2013. I believe that had Hastings been involved in the production of this film, he would have fiercely objected to the mannerism that Michôd and Pitt chose to represent the General. It is clear that Pitt is doing his very best impersonation of a cartoonish buffoon of a self-indulgent General that has lost a significant portion of his grasp on reality.

That the role called for Pitt to parody McChrystal to some extent is a given, and no character portrayed in the movie comes off looking good, with the exception of the narrator and Rolling Stones journalist. But it feels unrequited to have made the character such an immensely out of touch and poor facsimile of the individual it set out to depict. Whereas McChrystal is an intensely intelligent man, known for his reverence towards his men, Pitt’s General McMahon is nothing but an obtusely pudgy and naive, baby-faced clown.

As if this were not enough of a problem, Pitt’s unconvincing portrayal of the general appears wooden and flat, at best, suited for daytime TV. The performance can be likened to the over-the-top John Wayne impersonation one might drunkenly perform at a Christmas Party. “Hello Pilgrims,” indeed.

The best performance in the film is probably by Sir Ben Kingsley, who plays the role of Afghan President Hamid Karzai. Karzai comes across as a drug addled cynic who knows full well what his role is, and is pleased that McMahon tries to include him in any decision making process.

When we understand that slide, we’ll have won the war.

– General Stanley McChrystal

The film attempts to undermine, if not ridicule, the counterinsurgency (COIN) stratagem to a point that borders on reductio ad absurdum; reducing a complex and modular strategy into barely heard sound bites.

The majority of the scene where the strategy is explained, focuses on a German journalist played by Tilda Swinton, who has launched on a crusade against the General and the strategy. Legitimate concerns are voiced by Swinton’s character, but at the cost of the viewer not finding out what it is that she is crusading against – only what she is crusading for.

Yet despite its shortcomings, the film has some good qualities.

For starters it does a fair job of showing the futility felt by most Afghan veterans. We know full well that the Taliban only has to wait us out. America and its NATO allies are counting the seconds until they are able to leave Afghanistan. When that happens the Taliban can win without firing a single shot.

In one scene we are delightfully shown how difficult it is to train and operate with the Afghan National Army (ANA). The film displayed ANA soldiers for what they often are, drug fueled and lethargic. The film does an equally enjoyable job of showing the difficulty military members face fighting unpopular wars. They often find the back office crowd in DC will go out of the way to avoid being tainted by the war. McMahon barely gets any face time with the President, instead he has to deal with far-removed from the battlefield politicos at the State Department and the Pentagon telling him how the war should be fought.

For political reasons. Do not ask for more troops, do not make waves, just sit your time out, leave it to the next guy.

When McMahon finally receives some much anticipated face time with President Obama, played by Reggie Brown, it turns into just a photo op of no consequence. The President comes across as uninterested in the conflict. He also seems reluctant to spend more than a minute per quarter to meet with his premier general, newly appointed to the longest running conflict America has ever faced.

The film also delves into, albeit the shallow end of the pool, McChrystal’s attempts to increase, yet streamline, the American military presence in Afghanistan.

The Afghan strategy that McChrystal laid out before the world in 2009 is much the same as the one that President Trump is now, in all but name, using. In mid April of 2017, President Trump approved the new American, and by extension, new NATO/Afghan strategy. The strategy calls for 50,000 more US troops. In the film we see General McMahon fight bitterly for an additional 40,000 US troops, and “only” get 30,000. (General McChrystal actually requested 80,000 in his infamous “We are going to Win” strategy report, but was told by his Washington handlers aka advisers that he should ask for half that and then increase the number slowly). McChrystal’s intent was to perform a surge in COIN, with hearts and minds being at the center. A necessary, but costly, approach.

In order to get that far, McChrystal had to corral the unwieldy European ally base, gaining favor and the promise of additional troops from them. In “War Machine” we see McMahon mirroring those same moves – albeit with suitably less finesse and style than McChrystal reportedly displayed.

Presently, there are about 8,400 US troops fighting in Afghanistan. Today, President Trump is himself having to perform much the same act of war diplomacy, having found the situation not changed very much since McChrystal’s or McMahon’s days. America stands firm in its unwillingness to fully recommit to a complex war that most feel has already been lost, or should have been won over a decade ago. The complex nuances of Afghanistan make any attempts at presenting it to the public as clear as mud. On May 27th, Trump called for a significant increase of Australian troops to be deployed to Afghanistan. Similar calls are expected to be aimed at the Germans, the French, and the British, in the coming weeks.

With Afghanistan being America’s longest running war, it is pleasing to see real attempts being made to represent it in a bitterly satirical fashion. “War Machine” seemingly fails on the whole. Though it did quite well in showing how the true enemy in Afghanistan is not just the Taliban, but that the long standing culture of Afghanistan runs counter to democratic values. The movie still left me feeling that these things are best done by either telling an individual story on a non-strategic level, keeping it on the tactical-satirical level, or by creating a buffer for the viewer. A buffer in the same vein that M*A*S*H* offered up, dividing the crass actualities and realities of war on the strategic level with more easily digested mockery of the absurdity that is war and politic. This M*A*S*H was able to do with quotable sound bites, yet leaving us with an understanding of the raw brutality of the human condition at war.

The film’s tagline, “We’re Gonna Liberate the Sh** Out of You,” made me wonder how producers were able to liberate the $60 million Netflix spent on making it.

I give “War Machine” 4/10 Lima Charlie (LC)-Film points. I appreciate the effort, and the intent behind it, but believe that it turned out to be a misguided representation of events.

Directed by: David Michôd

Story by: David Michôd, based on “The Operators” by Michael Hastings

Starring: Brad Pitt, Anthony Hayes, Ben Kingsley, Anthony Michael Hall, Alan Ruck and Topher Grace

Production company: Plan B Entertainment

Distributed by: Netflix

Release date: May 26, 2017, worldwide streaming release

Run time: 122 minutes

John Sjoholm, Lima Charlie News

John Sjoholm is Lima Charlie’s Middle East Bureau Chief, Managing Editor, and founder of the consulting firm Erudite Group. A seasoned expert on Middle East and North Africa matters, he has a background in security contracting and has served as a geopolitical advisor to regional leaders. He was educated in religion and languages in Sana’a, Yemen, and Cairo, Egypt, and has lived in the region since 2005, contributing to numerous Western-supported stabilisation projects. He currently resides in Jordan. Follow John on Twitter @JohnSjoholmLC

Lima Charlie World provides global news, featuring insight & analysis by military veterans, intelligence professionals and foreign policy experts Worldwide.

For up-to-date news, please follow us on twitter at @LimaCharlieNews

![Image Strike a deal with which devil? The many faces of the Taliban [Lima Charlie News][Image: Anthony A. LoPresti]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/Many-faces-of-the-Taliban-Lima-Charlie-News-Anthony-LoPresti-480x384.png)

![Image The Killing of Osama Bin Laden. Is there a Doctor in the House? [Lima Charlie News]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/The-Killing-of-Osama-Bin-Laden.-Is-there-a-Doctor-in-the-House-480x384.png)

![Image NYPD in Afghanistan, ISIS suffers key setback [Lima Charlie News][NATO photo: Erickson Barnes]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/NYPD-in-Afghanistan-ISIS-suffers-key-setback-480x384.jpg)

![Image China's football fever and FIFA - a World Cup match made in heaven [Lima Charlie News]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/Chinas-football-fever-and-FIFA-a-World-Cup-match-made-in-heaven-480x384.png)

![Image Life after the Marine Corps - a 360 with skateboard artist Rafael Colon [Lima Charlie News]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/RafaelColon-480x384.jpg)

![Image Strike a deal with which devil? The many faces of the Taliban [Lima Charlie News][Image: Anthony A. LoPresti]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/Many-faces-of-the-Taliban-Lima-Charlie-News-Anthony-LoPresti-150x100.png)

![Image The Killing of Osama Bin Laden. Is there a Doctor in the House? [Lima Charlie News]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/The-Killing-of-Osama-Bin-Laden.-Is-there-a-Doctor-in-the-House-150x100.png)