OPINION: Fueled by Russian gas imports and the Nord Stream 2 pipeline, an energy Cold War threatens to divide Europe.

The European Union’s Energy Union initiative is a beautiful idea. An idea which is being crushed by harsh realpolitik. The controversy surrounding Nord Stream 2 reflects how the import of liquid natural gas (LNG) is dividing the European Union and raising geopolitical tensions between Russia and the U.S. The export of natural gas to Europe is but an instrument in the Metternichian styled toolbox of the strong-arm politics of Vladimir Putin and Donald Trump alike.

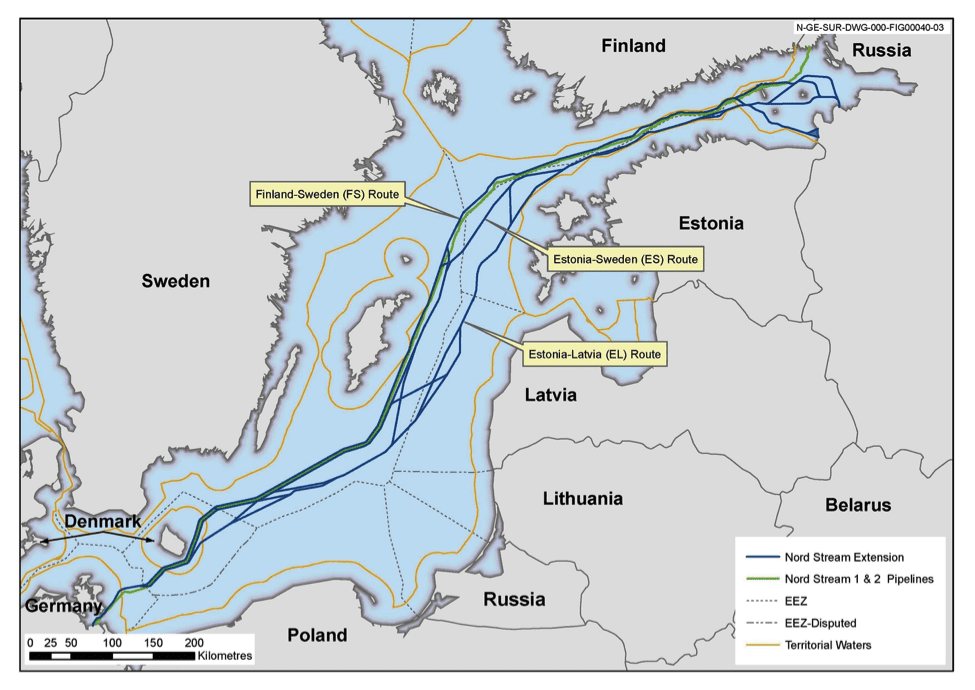

Nord Stream 2 is considered an intricate part of the EU’s energy expansion plan, which will supposedly ensure a resilient energy union utilising free market principles. The new gas pipeline is being built through the Baltic Sea, from Russia to northern Germany. The first pipeline, Nord Stream, was completed in November 2011 and measures 1,222 kilometres (759 miles) in length, making it the longest sub-sea pipeline in the world. In its present configuration, it has a capacity of 55 billion cubic metres (1.9 trillion cubic feet) of LNG-flowthrough per year.

If successful, Nord Stream 2, with its two additional lines, would double that capacity to 110 billion cubic metres (3.9 trillion cubic feet) by the end of 2019. Thus it stands to unravel the European Union’s energy sovereignty in favour of Russia.

We’re supposed to protect you from Russia, but Germany is making pipeline deals with Russia. You tell me if that’s appropriate. Explain that.

-President Donald Trump, July 2018 NATO Summit

Who will turn on the lights?

The Nord Stream project has been fraught with controversy since its inception. Its opponents represent a wide array of interests and include geostrategic analysts, environmentalists and right-wing governments throughout Eastern Europe.

A primary concern stems from Europe’s increasing dependency on Russian natural gas. Between 2016 and 2017 natural gas imports from Russia to Europe increased by 5 per cent, meaning that 37 per cent of Europe’s natural gas imports came from Russia in 2017. Upon completion of Nord Stream 2 that figure would increase even more, rendering Europe unable to take a viable political or military stand against Russia should the need arise without hampering its own abilities to operate as a functional society.

Moscow’s willingness to use its natural gas pipelines as a weapon, be it justifiable or not, came into vivid display in 2006 and 2009, when Russia closed the proverbial tap on natural gas flowing to and through Ukraine. At the time, about 80 per cent of Russian gas exports to the European Union passed through Ukraine. This act, which was reminiscent of the 1973 oil crisis where OPEC sought to penalise the U.S. for siding with Israel during the Yom Kippur conflict, devastated European access to natural gas. Ostensibly, this was done largely in an attempt to force the Ukrainian state-controlled oil and gas company Naftogaz Ukrainy to pay its outstanding bills towards Russian government-owned Gazprom. The act served a secondary purpose.

For years Ukraine sought to join the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), a position deeply troubling for Moscow, which favoured Ukraine joining a Russian-led defence alliance. At the flip of a switch, Moscow showed Kiev just who made the lights come on in Ukraine.

Another geostrategic consideration, albeit less focused on the direct good of the Energy Union, is the consideration that a direct pipeline between Russia and Germany will weaken Ukraine’s position as a transit country. The prospect of weakening Ukraine is concerning in light of the Russian military annexation of Crimea and the ongoing Donbas situation. This would limit Kiev’s ability to sue for acceptable terms with Moscow.

With this in mind, it is no wonder that a U.S.-led coalition has critiqued the pipeline deal. During a July 2018 NATO summit in Brussels, both the Polish delegation and U.S. President Donald Trump expressed concern over Germany’s decision to approve of the pipeline, arguing it would make Germany “totally dependent” on Russian LNG.

Of course, the U.S. intent behind this ominous warning is not altogether altruistic.

Rather, the U.S. wants Germany, and Europe at large, to import its LNG from American suppliers. The U.S. has in recent years become a leading exporter of LNG and considers it a strategic goal to stop Nord Stream 2, allowing effective control the European market. Poland, which recently announced a long-term plan to stop all import of Russian LNG by 2022, has offered itself as a transit country for U.S. LNG to enter Europe. In fact, a stated U.S. goal is to become the world’s largest exporter and Europe’s main supplier of LNG by 2025. To help facilitate this reality, President Trump has directly and indirectly threatened sanctions targeting companies that are involved in the construction of the Nord Stream 2.

In addition to this, there are concerns within European countries that while the project would represent a Union–wide change in energy politics, impacting the entire continent’s energy security and sovereignty, the primary beneficiary in the short term is Germany. Germany could, should the political winds change, use its position as a routing point and hub for Russian LGN in much the same fashion as Russia did against Ukraine.

In light of these concerns, the Nord Stream projects have found resistance not just on local political levels, but also on a European Union-administrative level.

![Image [German Chancellor Angela Merkel, Russian President Vladimir Putin (AFP)]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/Merkel-Putin-01.jpg)

In Comrade Schröder We Trust

Today the project is being handled by Swiss consortium Nord Stream AG, with Russian government-owned natural gas giant Gazprom as its majority owner. Minority ownership is divided between energy companies from Germany (Wintershall and Uniper), Austria (OMV), France (Engie) and the Netherlands (Shell). The coalition is led by the former German Chancellor and Social Democrat Gerhard Schröder, decidedly pro-Russian and a confidant of Russian President Vladimir Putin. When Putin became Acting President of the Russian Federation in 1999, Schröder became one of his earliest Western allies. The ease with which the two leaders created a lasting relationship might have come, in part, due to the fact that Putin speaks fluent German after having served as a KGB agent under the guise of a translator while in Dresden, East Germany from 1985 to 1990.

Schröder would come to spearhead what became the Nord Stream project. In 2005, Schröder’s time as Chancellor came to an end. Just days before he was set to leave office, he signed a €1 billion government guarantee with Gazprom in case Gazprom faltered on its obligations. This would not just ensure Gazprom would build the pipeline, even if at the cost of the German government, it caused Gazprom stocks to soar.

Within a few weeks, Schröder was announced as the Chairman of the Shareholders’ Committee of Nord Stream representing Gazprom and, with it, Russian interests towards Europe.

![Image [Former German Chancellor Gerhard Schröder with Russian President Vladimir Putin]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/Schroeder-Putin-.jpg)

This was not the first time that Russia would hire exiting high ranking government officials to expedite its interests. In 2008, Nord Stream AG hired former Finnish prime minister Paavo Lipponen as a consultant to help change Nordic countries’ perception of the pipeline. Lipponen, a long-standing Finnish social democrat who served as prime minister from 1995 to 2003, had been an early supporter of the project. His administration was known as unusually Russia-friendly by Finnish standards. At the time, Lipponen still had an office in the Finnish parliament building but was forced to relinquish his quarters amidst the news that he had taken a job with Gazprom.

A few months later, Russia initiated a military operation against neighbouring Georgia. Lipponen seized the opportunity and terminated his consulting contract with Gazprom. Almost immediately afterwards, in an attempt to recuperate some of his public image, he would pen an article in the Finnish news magazine Tekniikka & Talous criticizing his former employer. In the article, Lipponen warned that Europe was becoming overly dependent on Russian gas, suggesting that nuclear power was a better option.

Schröder, on the other hand, took a different path. A significantly more recognizable personality on the European political stage, Schröder would come to openly advocate pro-Russian dogma. For instance, during the initial days of the Russian incursion into Ukraine, Schröder was one of the few Western European politicians to loudly oppose the imposition of sanctions or European Union condemnation of Russia’s actions.

I see that the United States is interested in a weaker Russia, and the interest of Europe and Germany is that Russia will prosper …

— Gerhard Schröder at the Eurasian Economic Forum in Verona in October 2017

Schröder would become chairman of government-controlled Russian oil giant Rosneft in 2017. At the time Rosneft remained under U.S. sanctions due to the Ukrainian crisis, though Schröder would avoid being added to the sanctions list. This would lead to Ukraine’s Foreign Minister Pavlo Klimkin to call for targeted sanctions against Schröder. In a March 2018 interview with German newspaper Bild, Klimkin stated, “Schröder is the most important lobbyist for Putin worldwide.” Klimkin went on to state, “it is important that there are sanctions against those who promote Putin’s projects abroad”. Present German Chancellor, Angela Merkel would also criticize her predecessor.

While Schröder serves on the Rosneft board, he remains the Nord Stream 2 manager on behalf of Gazprom.

Via Media! A compromise

For the past few months, Nord Stream 2 has received increasing resistance from France, Belgium and the U.S., along with the Baltic States. On February 7th, 2019 a French Foreign Ministry spokeswoman stated that France would support a European Commission proposal which would seek to disrupt the final stages of the project. This move would not just jeopardize the project, it could cause a dramatic head-on collision between France and Germany mere days after signing a new friendship agreement, the so-called Aachen Treaty (formally known as the Treaty on Franco-German Cooperation and Integration).

At the same time, officially unrelated and not at all intending to show the urgency of the matter, French President Emmanuel Macron announced the cancellation of his appearance at the Munich Security Conference, where he was scheduled to give a joint address with Merkel. The intended topic was said to be a united Europe and the need for security. Macron’s relationship with Russia is a complicated one, rooted firmly in realpolitik and subject to developments de jour. While Macron has advocated for an EU initiative to create a military force rivaling NATO, to eliminate reliance upon the U.S. for Europe’s security needs, he has also advocated the creation of a strategic partnership with Russia.

France’s position placed Chancellor Merkel firmly between a rock and a hard place. By endangering completion of the Nord Stream 2 project, it could be the final nail in Merkel’s political coffin. In recent years, Merkel has suffered from an increasingly weakened position on the domestic political scene. She can no longer afford to be viewed as unable to keep promises made to her constituents. As such, Merkel is desperate to complete the pipeline, as Germany needs to replace the remaining DDR-era nuclear and coal power plants that Merkel committed to phasing out in the coming years.

On February 8th, less than twelve hours after Macron’s announcement, a “compromise” was reached which would make the completion of Nord Stream 2 possible. As part of the agreement, Germany and France will both sponsor a new European Commission proposal to be approved by the Member States. If it passes, it would mean that the same rules which already apply internally within the EU would apply to imports. Ultimately, this translates to the precondition that Nord Stream 2 cannot be owned or operated by the same company that produces the gas.

![Image [German Chancellor Angela Merkel and French President Emmanuel Macron sign Treaty of Franco-German Cooperation and Integration, Aachen, Germany, Jan. 22, 2019 (Photo: Ludovic Marin / AFP)]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/Macron-Merkel-friendship-treaty.jpeg)

The European Commission has stated that its Energy Union will put further emphasis on the importance of limiting dependence on Russia as the largest gas exporter. Berlin, in turn, has tried to assuage the situation further by announcing that it is studying the possibilities of constructing two additional terminals on the North Sea coast to receive LNG from the U.S.

While the source of Europe’s natural gas needs will continue to be a controversial issue for the foreseeable future, these measures are necessary to move towards a more sustainable long term energy policy.

What about alternative energy solutions? For some, the solution includes reinvesting in more modern and readily available nuclear fusion solutions. Fracking is another controversial but credible and cheaper alternative to Russian gas. This is a route that only the UK, which is already integrated into the European gas pipeline networks, appears willing to go down for now. In the meantime, the European Union has invested significant resources into the development of viable alternative energy sources, such as fusion and concentrated solar power technologies. However, true results are estimated to take at least another 15 to 30 years.

Regardless of what happens, dependency is never a pretty thing. The current situation holds every potential of creating a devastating weapon for the reigning superpowers to wield over Europe.

John Sjoholm, Lima Charlie News

John Sjoholm is Lima Charlie’s Middle East Bureau Chief, Managing Editor, and founder of the consulting firm Erudite Group. A seasoned expert on Middle East and North Africa matters, he has a background in security contracting and has served as a geopolitical advisor to regional leaders. He was educated in religion and languages in Sana’a, Yemen, and Cairo, Egypt, and has lived in the region since 2005, contributing to numerous Western-supported stabilisation projects. He currently resides in Jordan. Follow John on Twitter @JohnSjoholmLC

Lima Charlie provides global news, featuring insight & analysis by military veterans and intelligence professionals Worldwide.

For up-to-date news, please follow us on twitter at @LimaCharlieNews

In case you missed it:

![Image Russia's energy divides Europe [Lima Charlie News]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/Russias-energy-divides-Europe-Lima-Charlie-News.png)

![Image Little choice for Russia and China but to link up [Lima Charlie News]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/headlineImage.adapt_.1460.high_.russia_china_opinion_052114.1400674740238-480x384.jpg)

![Image Russian aluminium giant Rusal’s woes continue, but with a short reprieve [Lima Charlie News][Image: James Fox]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/bleh-480x384.png)

![Image 'Sanctions and the Rise of Putin's Russia' - starring oligarchs, siloviki, Rossiyskaya mafiya and Oleg Deripaska [Lima Charlie News]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/Putin-oligarchs-Lima-Charlie-News-480x384.png)

![Africa’s Elections | In Malawi, food, land, corruption dominate [Lima Charlie News]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/Malawi-election-Food-land-corruption-480x384.jpg)

![Syria’s oil, gas and water - the Immiscible Solution to the War in Syria [Lima Charlie News][Photo: ANDREE KAISER / MCT]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/Syria’s-oil-gas-and-water-480x384.png)

![Image The Rwandan Jewel - Peacekeepers, Conflict Minerals and Lots of Foreign Aid [Lima Charlie World]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/Rwanda-Jewel-480x384.jpg)

![Image The Trouble With Turkey’s Economy [Lima Charlie News]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/Trouble-with-Turkeys-Economy-01-480x384.jpg)

![Image Little choice for Russia and China but to link up [Lima Charlie News]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/headlineImage.adapt_.1460.high_.russia_china_opinion_052114.1400674740238-150x100.jpg)

![Image Russian aluminium giant Rusal’s woes continue, but with a short reprieve [Lima Charlie News][Image: James Fox]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/bleh-150x100.png)