Order was once built; its absence is now assumed.

Europe is not undergoing an ideological shift, but an analytical collapse. Great powers have not changed their behaviour. What has eroded is Europe’s capacity to understand the language and application of power. The consequence is functional rather than normative: loss of strategic autonomy, impaired collective action, and declining relevance in a multipolar system. Analysis has been displaced by self-deception.

“Mittel Energie auszuüben und nur ihn anzuordnen der Energie besitzt kann sie ausüben. Dieser direkte Anschluß der Energie und der Richtlinie bildet die grundlegende Wahrheit aller Politik und den Schlüssel zu aller Geschichte.”

— Ludwig von Rochau

In a multipolar world, Europe is not morally threatened, but strategically disarmed. Its geostrategic position increasingly lacks a coherent raison d’être. The problem is not that great powers again speak the language of power, but that this language is no longer understood by a continent that treats its own legitimacy as self-evident. Europe’s analytical framework has not been adapted to reality. It has been left unexamined.

Within Europe’s strategic tradition, Prince Klemens von Metternich served as a reference point for order-creating realism. Europe still invokes this legacy, but no longer practises it. Its political self-image remains built on giants, even as the systems they constructed have decayed. When order dissolves, Europe retreats to symbols rather than methods. Metternich built order through legitimacy, ritual, and restraint. This was not aesthetic preference, but political function: power disciplined to remain usable. Against this background, Donald J. Trump appears as Metternich’s antithesis. The comparison is structural, not moral. Metternich disciplined power. Trump articulates power in the absence of order.

What matters is not Trump’s conduct, but what the contrast exposes. Europe’s leadership cannot operationalise the inheritance it continues to cite. Trump is therefore not a realist in any classical sense. He operates in the vacuum created when order is abandoned yet presumed. This is not realism, but modern gunboat diplomacy in the Palmerstonian tradition: power exercised without institutional restraint or legitimising ritual. The issue is not individual acts, but precedent. Raw interests are again articulated openly. Had a smaller state behaved in this manner, it would have been delegitimised without hesitation.

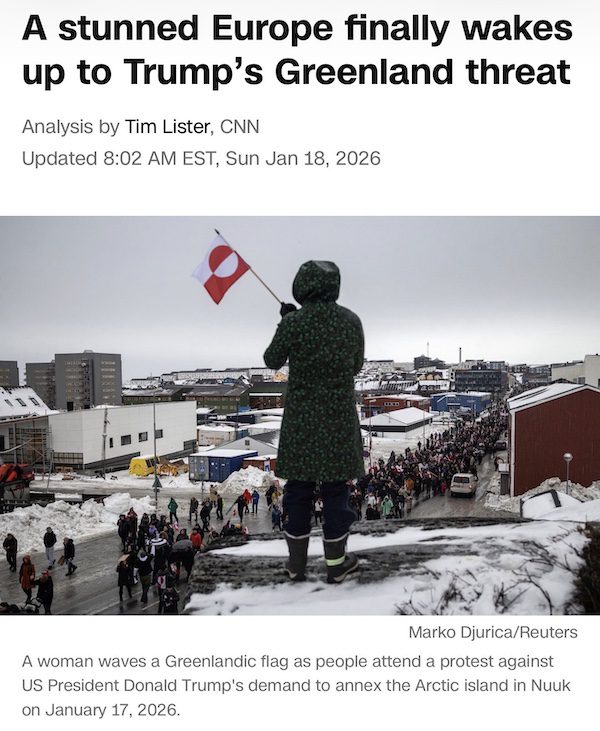

The Greenland manoeuvres must be understood accordingly. They were not driven by territorial necessity, but by system pressure. Greenland functioned as a stress test of Europe’s dependencies and bargaining position. The United States already enjoys extensive military access via Denmark. Had the issue been operational, it would have been resolved quietly within existing arrangements. Its public execution was the signal. Greenland was not the objective. It was the instrument.

This episode reflects a broader shift. Great powers again compete openly over territory, resources, and strategic position, without decorative frameworks. The dismantling of cooperative arrangements and Russia’s territorial ambitions point in the same direction: an accelerating contest over control of critical areas.

In this environment, European agency is no longer optional. When order is no longer supplied externally, it must be produced internally. This is not ideological ambition, but structural necessity. Europe is only now confronting the reality that its agency and latent great-power capacity were, in practice, delegated to an external actor with its own interests and priorities. This was not the result of strategy, but of accumulated convenience and normative self-understanding.

American reprioritisation is frequently misread in Europe as ideological retreat. In reality, it is a classical exercise in power logic. The United States is reallocating strategic bandwidth, not withdrawing from the world.

American strategy is reverting to familiar priorities: dominance in the Western Hemisphere to free capacity for Asia, above all China. From Washington’s perspective this is coherent. For small states it means fewer guarantees, higher risk, and greater exposure to other nuclear powers. The outcome resembles isolationism, even if the motive is not withdrawal.

Europe is not deprioritised because it is weak, but because it is assessed as strategically finished. Militarily bound, institutionally integrated, and largely predictable, Europe requires management rather than constant strategic direction. This is why American focus can shift elsewhere without Europe remaining central.

Many European observers misread this as liberation from a rules-based order. They confuse intent with consequence. American strategy is interpreted through European ideological filters rather than on its own operational terms. In the absence of a strategic culture, the erosion of order is mistaken for autonomy. For small states, this produces exposure, not freedom.

Internally, Europe is poorly prepared for the world now taking shape. Fragmentation is structural as well as political. The asymmetry between France and Germany obstructs coherent strategic direction. France thinks in terms of power and sovereignty; Germany in terms of economics, norms, and internal stability. Eastern Europe’s security dependence on the United States further pulls the continent away from genuine European autonomy, regardless of rhetoric.

This is compounded by the absence of an integrated industrial and military base, and by the European Union’s recurring inability to act strategically without American leadership, intelligence, and military backbone. The irony is that this trajectory is often defended in the name of realism. Yet realism for small states is not about pride or symbolic sovereignty. It is about alliances, asymmetries, and survival. Balance of power is achieved through structure, not by dissolving it.

The Middle East illustrates the same logic. It fits neither East nor West. From an American perspective, it is a frontier zone to be externalised. Engagement has been reactive rather than designed, focused on crisis management rather than durable order. During Trump’s previous term, regional actors such as Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates were granted latitude to manage regional balances, while their dependence on American military power, technology, and expertise deepened. The region is not a strategic anchor, but a tool: stable enough not to distract from Asia, disordered enough to remain dependent.

Certain consequences follow. Security relationships diversify as risk management, not ideology. Domestic capacity matters not as independence, but as leverage. Autonomous freedom of action reveals itself as what it has always been: an illusion. What remains is redundancy, in alliances, supply chains, and security arrangements. There is nothing elegant in this development. Opportunities exist, but no beauty. Europe must become stronger and less fragmented, while accepting that the old order cannot be preserved intact.

Europe must again think in terms of grand strategy and great-power politics. Not as aspiration, but as necessity. This requires unification around pragmatic realpolitik, military and industrial capacity, and a willingness to compete for resources, influence, and strategic position. Ideological self-affirmation and normative rhetoric are luxuries. Power and structural control are prerequisites.

In a multipolar system, self-image does not survive. Only function does. Structures that cannot act are selected against, regardless of their normative coherence. For Europe, this leaves little ambiguity. If collective frameworks are to persist, they must operate as instruments of power rather than custodians of identity.

In this sense, the European Union remains the only viable mechanism through which small and medium states can retain strategic relevance. Not as a moral project, but as a functional one. This presupposes an ability to act decisively, including beyond Europe’s immediate perimeter, where access to resources, logistics, and emerging markets increasingly determines strategic resilience. Africa is not peripheral to this calculus. It is integral to it.

This is a generational problem. The political class formed at the end of the post-war period often lacks both instinct and mandate for such a transition. Europe will require decision-makers shaped by the realities of power rather than its language. History offers no guarantees, but it offers references: Prince Klemens von Metternich, Otto von Bismarck, Ludwig von Rochau, Charles-Maurice de Talleyrand-Périgord, and on Europe’s periphery, Carl Gustaf Emil Mannerheim. Not as ideals, but as functional examples of statecraft under structural pressure.

As Joseph de Maistre observed with characteristic economy: Toute nation a le gouvernement qu’elle mérite.

[Author’s note: This text is a translated, merged, and revised English version of two previously published Swedish-language essays by the author: “Realismens syn på amerikansk omprioritering, europeisk konsekvens” (2026-01-07) and “Europas Liberala Självbedrägeri” (2026-01-08). The argument has been consolidated and reformulated for an English-language readership.]

John Sjoholm, for LIMA CHARLIE WORLD

[Subscribe to our newsletter for free and be the first to get Lima Charlie World updates delivered right to your inbox.]

John Sjoholm is Lima Charlie’s Middle East Bureau Chief, Managing Editor, and founder of the consulting firm Erudite Group. A seasoned expert on the Middle East, North Africa, Europe and the Balkans, he has a background in security contracting and has served as a geopolitical advisor to regional leaders. He was educated in religion and languages in Sana’a, Yemen, and Cairo, Egypt, and has lived in the region since 2005, contributing to numerous Western-supported stabilisation projects. He currently resides in Jordan.

Lima Charlie World provides global news, featuring insight & analysis by military veterans, intelligence professionals and foreign policy experts Worldwide.

For up-to-date news, please follow us on twitter at @LimaCharlieNews

In case you missed it: