In 2017, several noteworthy elections occurred across Europe. Arguably, the two most significant were the French presidential and German federal elections. The results hold the potential to revive Europe’s drive towards greater integration by shifting the balance of influence within the European Union.

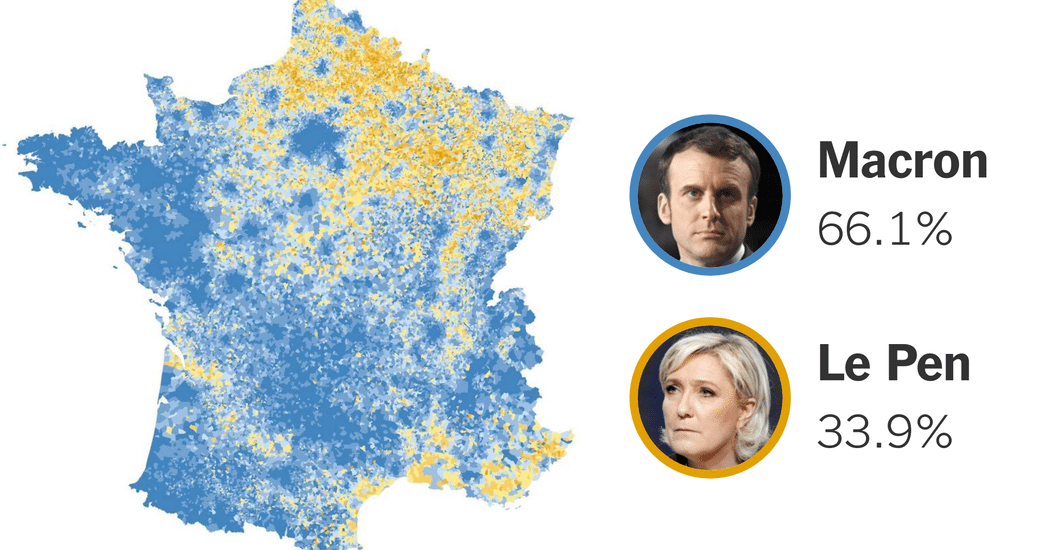

In the French election, Emmanuel Macron, a pro-European centrist and the former Minister of Economy and Finance, won a commanding 66.1% of the vote against the avid right-wing nationalist, Marine Le Pen of the National Front (FN).

![Image German elections 2017 [Image: Lima Charlie News]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/German-elections-2017-Lima-Charlie-News-graphic.png)

Now, for the first time, the balance of power in the Franco-German relationship may be shifting towards the French, providing greater leverage in their attempts to reform the bloc.

Macron’s strong electoral victory and willingness to advance unpopular, but necessary, labor reforms in an effort to improve France’s international economic competitiveness has provided a degree of credibility among his European counterparts in his drive to reform the union. However, some across the continent, most significantly the Germans, remain skeptical and have reservations about any reforms that aim to solve the EU’s economic malaise through deeper integration, specifically with regard to monetary policy.

![Image German Chancellor Angela Merkel [AFP / TOBIAS SCHWARZ]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/Angela-Merkel-2017.jpg)

The German public, however, was reluctant to continue its support of eurozone members without their commitment to enact structural reforms that would bring their debt-to-GDP ratio down to manageable levels. The resulting fiscal austerity, the efficacy of which was questioned by some economists, targeted national public expenditures and welfare spending, adding to the economic hardship felt by the general population. Nonetheless, the German-favored fiscal discipline approach has remained the rule across the eurozone ever since.

With the recent German election results so unfavorable to Merkel, some observers have asserted that the prospects for EU reform have been diminished. Ironically, while these results may have curtailed Merkel’s domestic political maneuverability, they may also leave the chancellor with few options besides greater cooperation with Macron.

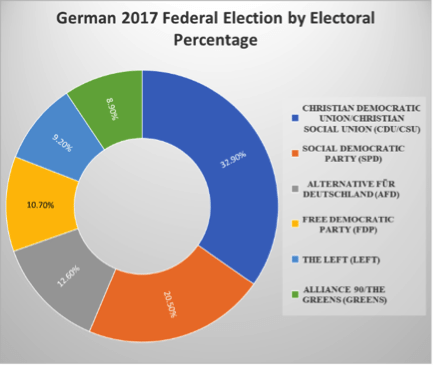

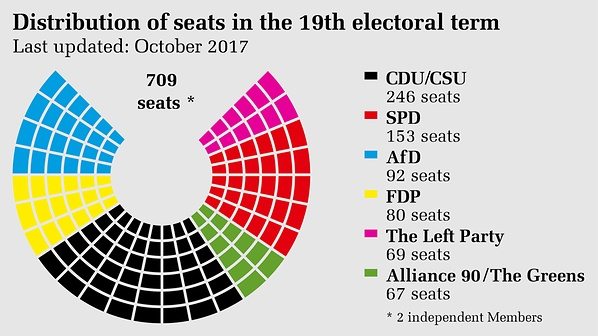

Currently, Merkel’s Christian Democrat alliance includes the national Christian Democratic Union (CDU) and its Bavarian sister party the Christian Social Union (CSU). Together, they are working to form a governing coalition that would provide a majority in the Bundestag.

As Merkel is loath to work with the AfD, there are four potential options. The first would be to call for fresh elections, which is seen as unlikely because it could further strengthen the AfD in the Bundestag.

The second option would be to resume the “grand coalition,” meaning the CDU/CSU would continue to work with the Social Democratic Party. (After the electoral loss, the SPD had been hesitant to maintain the coalition, but the parties have resumed negotiations.)

The third option would entail creating a governing partnership the Germans have taken to calling the “Jamaica coalition,” as the relevant parties share the same colors as the Jamaican flag. This alternative coalition would bring together the CDU/CSU, as well as the Greens and the pro-business Free Democratic Party (FDP), but the wide ideological gaps between the parties makes this option less viable. Finally, Merkel could take the unprecedented option of forming Germany’s first minority government.

Considering the potential governing coalitions, the most viable options would all see Merkel’s new partners open to, if not eager for, a closer relationship with Macron. Given Merkel’s weakened position, a resumption of the “grand coalition” would require her to make more concessions to the SPD.

Martin Schulz, leader of the SPD, has publicly voiced his support for Macron’s reforms and a continuation of the “grand coalition” would almost certainly mean enhanced cooperation with France. The “Jamaican Coalition” negotiations have collapsed as the parties’ ideological divides are simply too wide to be bridged. A minority government would only be able to pursue an agenda that could hope to garner a majority in the Bundestag. A move that would, again, most likely rely on SPD support, hence increasing the chances of collaboration with France.

Serving as chancellor since 2005, Angela Merkel has established a reputation as a competent steward of the German economy and a stabilizing force on the international stage. Merkel has maintained staunch opposition to the AfD throughout her political career and would likely see it as a mark on her legacy if her choices in forming a new government strengthened the far-right party’s position once she departs from German domestic politics.

Given the available options, it may become a political necessity for Merkel to embrace Macron’s aspirational vision of the European Union. While the world must wait to see what type of government Germany ultimately forms, we are all afforded a moment to reconsider an adage that’s common amongst EU diplomats, that the European Union serves to hide the strength of Germany and the weakness of France.

LIMA CHARLIE NEWS, with Sean McNicholas

Lima Charlie provides global news, insight & analysis by military veterans and service members Worldwide.

For up-to-date news, please follow us on twitter at @LimaCharlieNews

In case you missed it:

![Image Has there been a shift in Europe's balance of power? [John MACDOUGALL / AFP]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/Has-there-been-a-shift-in-Europes-balance-of-power-John-MACDOUGALL-AFP.jpg)

![Image Ambitions Never Laid to Rest - An Open Society vs. The Terrorist [Lima Charlie News] (Image: Patrick Hertzog)](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/Screen-Shot-2018-12-28-at-2.37.54-PM-480x384.png)

![Image En Marche! France’s economy stands at a crossroads and for Macron, failure is not an option [Lima Charlie News]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/En-Marché-France’s-economy-stands-at-a-crossroads-and-for-Macron-failure-is-not-an-option-480x384.png)

![Image Macron ignores domestic pressure, attempts take the lead of Western diplomacy in Syria [Lima Charlie News][Image: Reuters / Stephane Mahe](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/2018_04_08_43616_1523165065._large-1-480x384.jpg)

![Africa’s Elections | In Malawi, food, land, corruption dominate [Lima Charlie News]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/Malawi-election-Food-land-corruption-480x384.jpg)

![Syria’s oil, gas and water - the Immiscible Solution to the War in Syria [Lima Charlie News][Photo: ANDREE KAISER / MCT]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/Syria’s-oil-gas-and-water-480x384.png)

![Image The Rwandan Jewel - Peacekeepers, Conflict Minerals and Lots of Foreign Aid [Lima Charlie World]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/Rwanda-Jewel-480x384.jpg)

![Image Russia's energy divides Europe [Lima Charlie News]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/Russias-energy-divides-Europe-Lima-Charlie-News-480x384.png)

![Image Ambitions Never Laid to Rest - An Open Society vs. The Terrorist [Lima Charlie News] (Image: Patrick Hertzog)](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/Screen-Shot-2018-12-28-at-2.37.54-PM-150x100.png)

![Image En Marche! France’s economy stands at a crossroads and for Macron, failure is not an option [Lima Charlie News]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/En-Marché-France’s-economy-stands-at-a-crossroads-and-for-Macron-failure-is-not-an-option-150x100.png)