How did Turkey go from rapid growth to economic crisis so quickly? The Turkish economy has become a truly perplexing case.

Investing in emerging markets is always a risky game to play. Trying to sift through volumes of information and then place it in the proper context when some of the most reliable sources are not even available in English, can leave a novice investor befuddled. But even by the standards of emerging markets, the Turkish economy has become a truly perplexing case.

A short time ago, Turkey looked like a great opportunity for robust returns. Turkey has averaged 5.8% GDP growth since 2002 and is now the 13th largest in the world by purchasing power parity. In 2017, Turkey grew faster than India or China. As recently as last November, emerging markets guru Mark Mobius said that it was time to buy Turkey because he thought it presented excellent prospects for 2019.

Things look very different just a few months later.

Turkey is in the grips of a currency crisis, beset by 20% inflation and 11% unemployment, and facing a political showdown over who will control the country’s central bank. How did Turkey go from rapid growth to economic crisis so quickly? What went wrong?

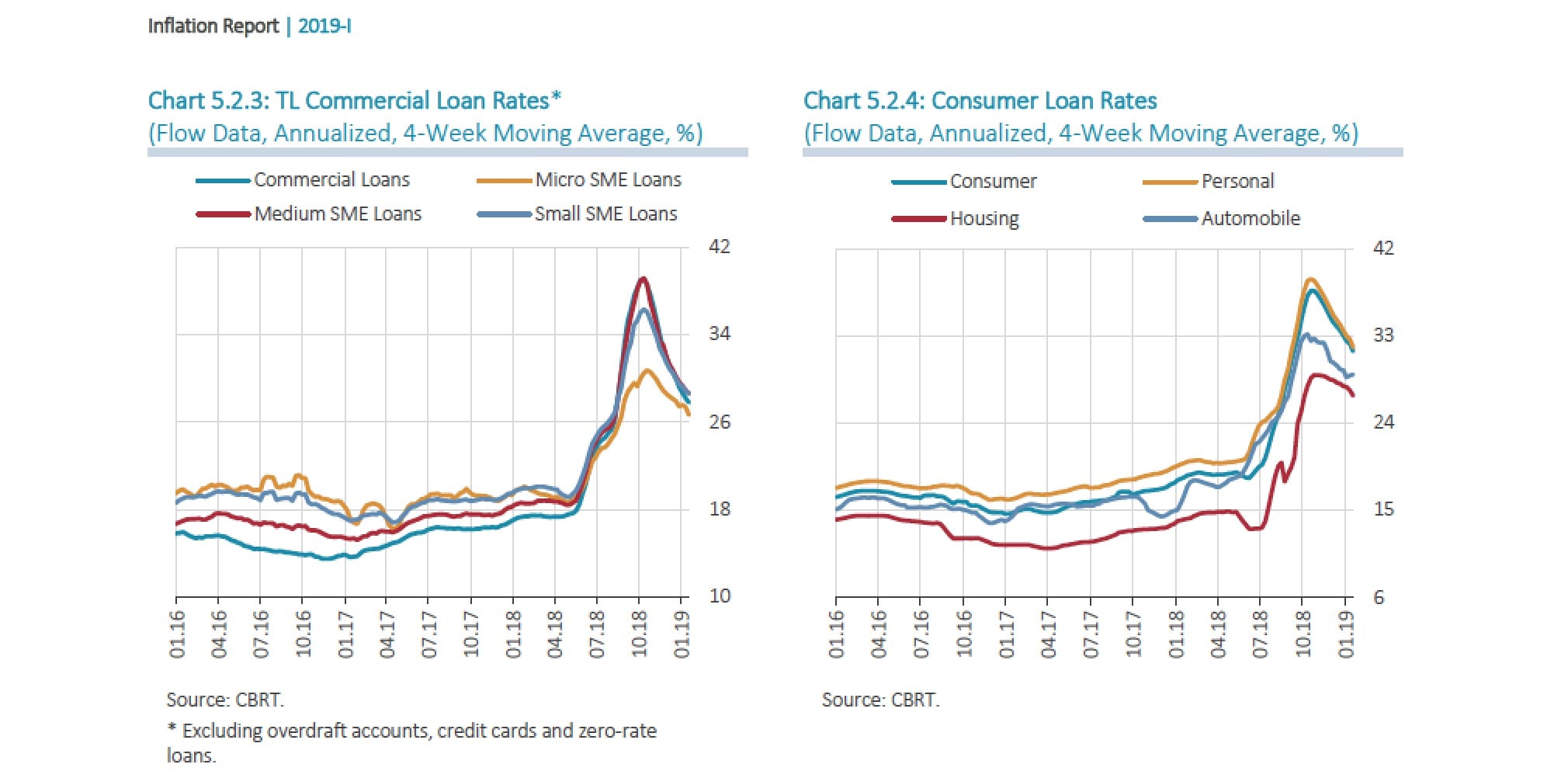

The President of Turkey does not directly control interest rates, but Erdogan has used his influence to push rates down. His ability to affect monetary policy has only grown as he has consolidated power. Just last summer, he gained the authority to appoint the central bank’s Governors.

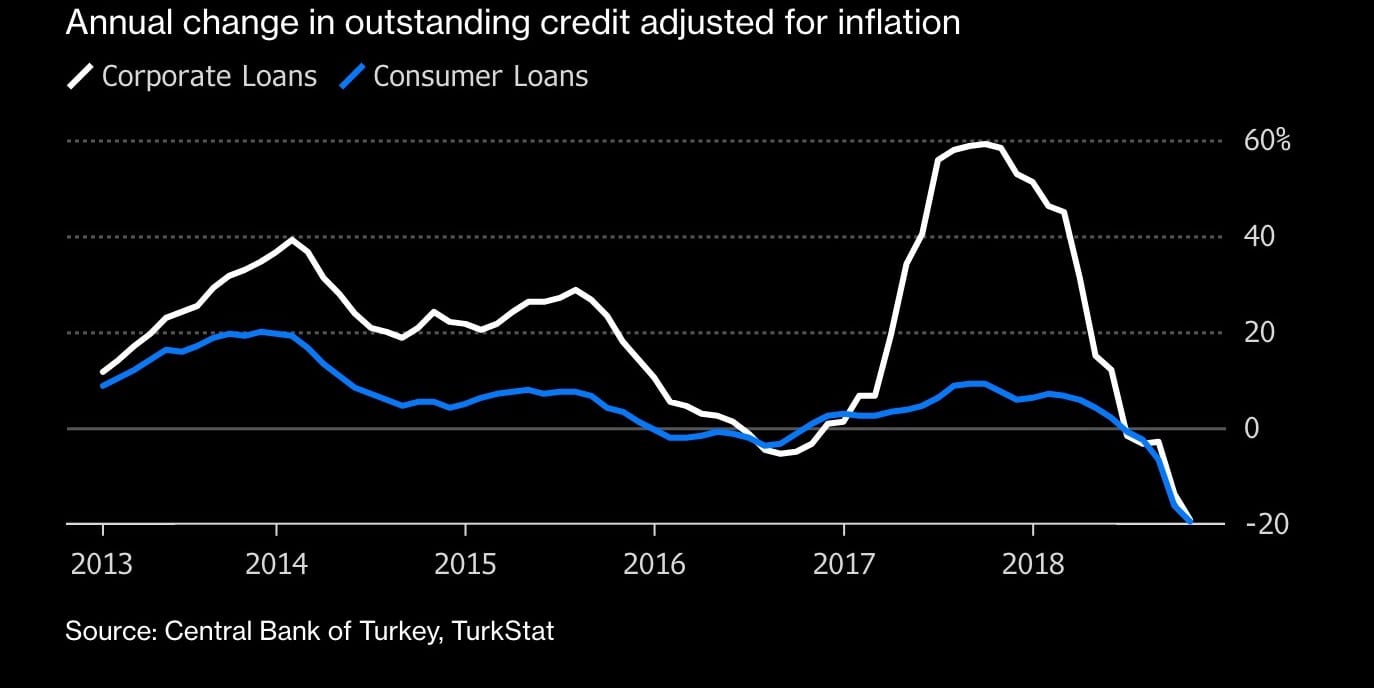

The result was a prolonged economic expansion fueled by easy credit. There was a boom in construction fueled by easy loans in real estate. There was growth in manufacturing output driven by business lending.

Consumer loans were one of the greatest areas of credit growth. Consumer loans constituted about 4% of Turkey’s economy in 2002 but in recent years that number has been closer to 18%. The emergence of cheap credit was a huge structural shift and it drove rapid growth across nearly all sectors of the economy.

[Download the full Central Bank of the Republic of Turkey (CBRT) 2019 Inflation Report]

Rapid growth caused by easy money is one of the oldest stories in economics. In Turkey’s case, there was a dangerous wrinkle: the loans were denominated in foreign currency.

Unlike the United States or Europe, where borrowers nearly always run up debts that can be paid back in their own currency, borrowers in emerging markets often borrow in foreign currency. This approach leaves emerging markets vulnerable to changes in the relative value of currencies. (If the emerging market sees its currency fall in value, it can be much more expensive to pay back the foreign loans). It requires them to hold reserves of foreign hard currency to pay off foreign debts.

The mechanics of this problem can be illustrated by a simplified example. Let’s say a consumer in Istanbul takes out a loan for one thousand Turkish Lira (about $188) from a commercial bank. The bank was able to get access to the necessary capital to make this loan by borrowing on international markets in Euros or US Dollars. The consumer is going to pay back his loan in Turkish Lira but if the value of the Lira falls, the one thousand Lira the bank collects when the loan is paid back may no longer be enough to pay off the foreign debt.

Multiply this across billions in loans to millions of borrowers and you have the classic recipe for an emerging market financial crisis.

This is what’s happening in Turkey right now. A year ago, one Lira was equal to about 26 cents. Today, it’s down to about 19 cents. That is a substantial decline of about 27%. Among major currencies, only the Argentine Peso fared worse over that time. This is a problem because Turkey’s foreign debt ballooned to nearly $470 billion by early 2018, an 18% increase from the summer of 2016. After a hard year of deleveraging, Turkey’s foreign debt is still at $450 billion – more than 50% the size of the entire Turkish economy.

This slammed the breaks on Turkey’s economic growth.

After a hard 2018, where does Turkey stand today? The interest rate hike imposed serious costs on the real economy. Industrial output has been falling for months and unemployment has risen by almost 20% in the last year. On the positive side, the Lira’s free fall has ended.

Turkey remains seriously vulnerable to a balance of payments crisis because of its large foreign debts and depleted currency reserves. However, one salutary effect of economic trouble is that Turkish consumers are spending less on imported goods. More conservative spending behavior and a drop in oil prices have left Turkey with a small net current account surplus in recent months. Turkey is slowly rebuilding its cash position and adding to its foreign currency reserves instead of depleting them.

None of this is cause for excitement for investors. Turkey appears to be moving from an acute crisis to a prolonged slowdown. Yes, the currency has stabilized and current accounts are being replenished, but the size of Turkey’s foreign debts means the process will take many years. Turkey can stabilize its balance of payments if consumers spend less but it can’t return to dynamic growth unless they spend more. Turkey is now trapped by the very debts that allowed it to grow so quickly for so long.

Investors should not hold their breath waiting for a quick turnaround.

John Ford, for Lima Charlie News

John Ford is an attorney in California and a reserve officer in the US Army. He writes about global strategy and international economics, focusing on the Asia Pacific. You can follow him on twitter at @johndouglasford.

For up-to-date news, please follow Lima Charlie on twitter at @LimaCharlieNews

In case you missed it:

![Image The Trouble With Turkey’s Economy [Lima Charlie News]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/Trouble-with-Turkeys-Economy-01.jpg)

![Image Opinion | Turkey trades Democracy over promises of greatness [Lima Charlie News][Photo: Lefteris Pitarakis / AP]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/Turkey-trades-Democracy-over-promises-of-greatness-480x384.png)

![Image Erdogan's high wire act keeps Turkey's economy spinning, for now [Lima Charlie News]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/Screen-Shot-2018-05-04-at-5.22.24-PM-480x384.png)

![Image This Week in Business Intelligence [Lima Charlie News]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/This-Week-in-Business-Intelligence-Lima-Charlie-Business-Intel-Report-480x384.png)

![Blossoming Russo-Turkish alliance leaves U.S., NATO behind [Lima Charlie News]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/Russia-Turkey-alliance-leaves-U.S.-NATO-behind-480x384.png)

![Image Opinion | Turkey trades Democracy over promises of greatness [Lima Charlie News][Photo: Lefteris Pitarakis / AP]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/Turkey-trades-Democracy-over-promises-of-greatness-150x100.png)

![Image Erdogan's high wire act keeps Turkey's economy spinning, for now [Lima Charlie News]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/Screen-Shot-2018-05-04-at-5.22.24-PM-150x100.png)