An unusually long German winter, too many sick days, a union strike, Trump’s trade war and the U.S. withdrawal from the Iran Deal are just some of the factors that may be contributing to Germany’s recent economic downturn. Or it could be just a normalisation of the German economy. Lima Charlie’s John Sjoholm asks the experts.

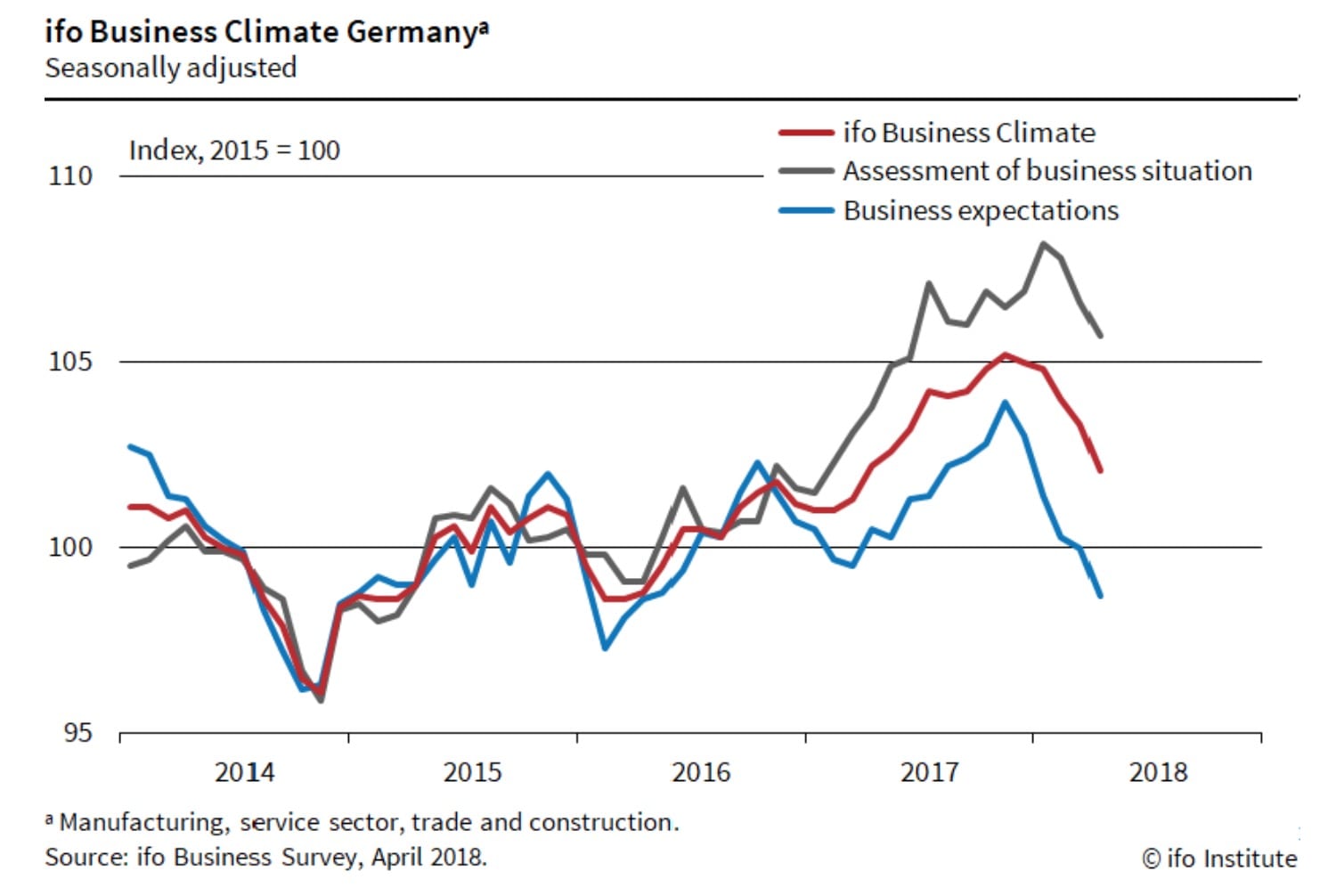

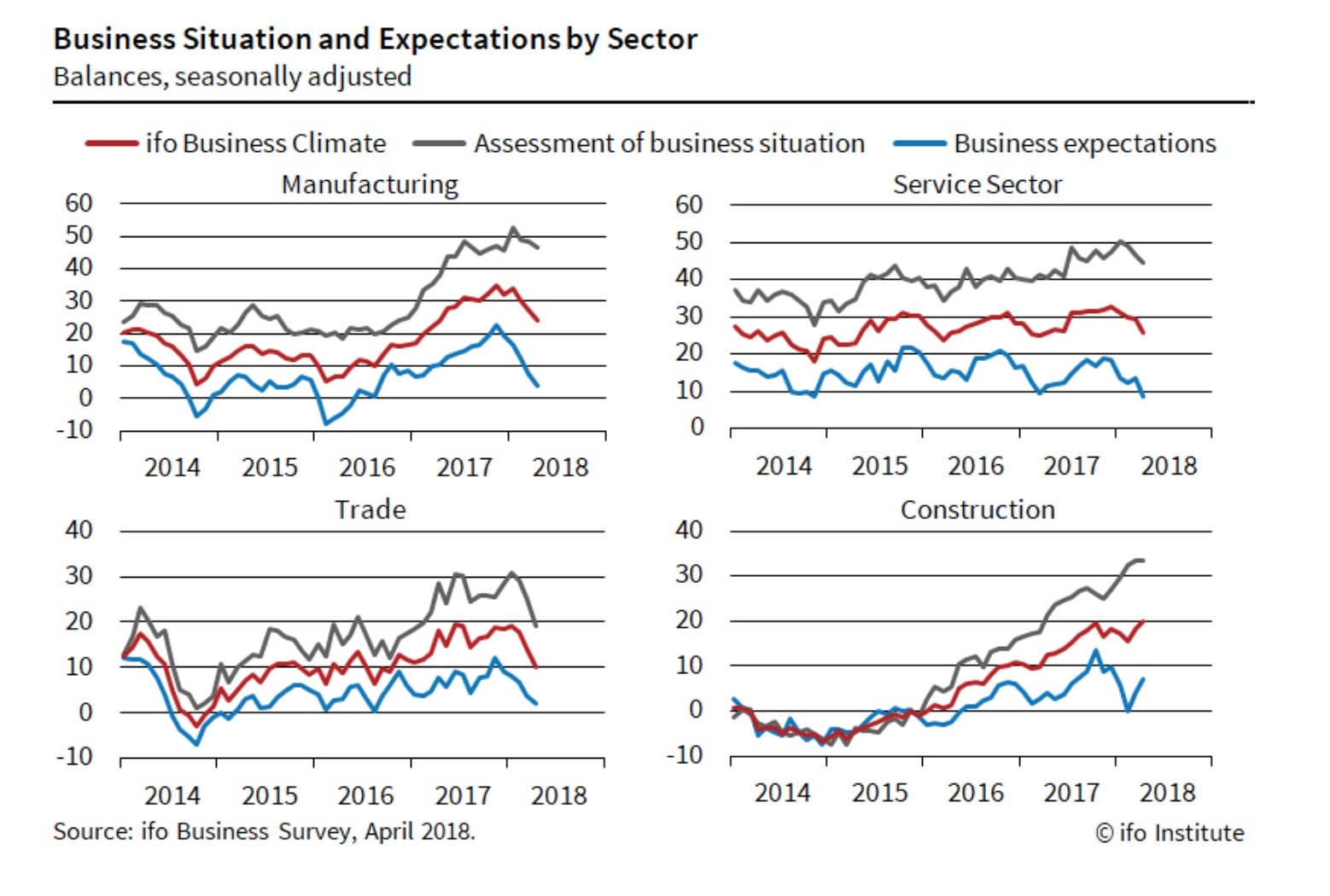

Influenza has hit the German economy – literally. Too many sick days resulting from a long winter, may be partially responsible for a downturn in the GDP of Europe’s most significant economy. Germany’s Ifo Business Climate index, which measures the temperature of German companies, has dropped for a fifth consecutive month, giving analysts, executives and politicians alike the economic chills.

The Ifo index is a closely followed leading indicator for economic activity and is prepared by the Ifo Institute for Economic Research in Munich. It fell to 102.1 points in April, from 103.3 points in March. Apparently, part of the downturn arose because Germany’s economy had ended at an unusually high point during the fourth quarter of 2017, but was then followed by worldwide economic turbulence at the beginning of 2018, causing severe slowdowns.

Stefan Schneider, Chief Economist for the German Deutsche Bank, stated during a conference call with Lima Charlie News that “growth is no longer 0.6-0.7 percent per quarter in which we have become accustomed in recent years, but has become a bit slower.” Herr Schneider stated that he expects even lower numbers to be reported in the coming quarter, “somewhere between 0.2 and 0.3 percent.” Schneider clarified that “it is still over Germany’s long-term potential of 0.35 percent.”

The real question is if the first quarter of 2018 represents the beginning of a permanent slowdown, one for an economy that keeps the European Union largely afloat.

“It is too early to say that there will be a permanently slower growth rate. It is rather a normalisation,” said Schneider in response to this question. Schneider underlined that it is too early to make any doom and gloom predictions and that on the whole, German index levels are quite high.

“Germany has very robust employment with good wages growth. The government investment will rise.” However, he was quick to point out that “economists are not good at predicting the turning point. It is difficult to solve its forecast from the past when everything looks so good, and you only hear positive news.” Schneider added, “besides, you do not want to stand out when all other economists believe the upturn will continue.”

It was with this in mind that the Chief Economist at Deutsche Bank stated that the bank is sticking to its previous forecast of 2.3 percent German GDP growth for 2018.

Deutsche Bank’s forecast mirrors that of German State Bank KFW’s Chief Economist, Klaus Zeuner. In November 2017, Herr Zeuner predicted a GDP growth between 2.0 and 2.5 percent. Zeuner now believes that the German economy will see an upturn, but does acknowledge that the past quarters’ numbers indicate that a forecast correction might be forthcoming.

Deutsche Bank’s forecast mirrors that of German State Bank KFW’s Chief Economist, Klaus Zeuner. In November 2017, Herr Zeuner predicted a GDP growth between 2.0 and 2.5 percent. Zeuner now believes that the German economy will see an upturn, but does acknowledge that the past quarters’ numbers indicate that a forecast correction might be forthcoming.

“There is insufficient information to declare that the boom is over in the euro area and Germany, but the growth rate has probably reached its peak in 2017/2018,” said Zeuner. However, Zeuner does not believe that the recent downturn is an indicator of a coming recession stating, “The maximum capacity of German industry as you have suddenly started talking about, is nothing that occurred in January, but something that we need to handle a long time to come.”

Gesundheit!

Zeuner’s statement, however, stands in some contrast with Heinrich Bayer, Chief Economist at German Postbank. Herr Bayer stated, “the future does not look quite as rosy as before. At the beginning of the year, we discussed to even raise the (GDP) forecast to 3 percent, but that is no longer relevant. For 2019 the forecast is 1.8 percent. It is more a return to average growth.”

Herr Bayer attributes part of 2018’s weak beginning to the IG Metall trade union strike, and a disruption in supply chains due to a 1.5 times upswing in sick leaves for February. This, combined with an unusually prolonged German winter, slowed growth. “The winter was not very cold, but long, and stretched almost all the way into April,” said Herr Bayer.

Bayer followed up by pointing out that the economic upturn has not been going on for so long. “The euro area came out of recession in 2013, and it is really only in the last 1.5 years we have had good momentum in Germany.”

Iran, China and the Trump Trade War

All analysts agreed, however, that the past five months weakening of the Ifo index was in part due to the still ongoing trade dispute with the United States over import restrictions and new taxes on steel products. These new restrictions and costs, even if levied only against China – as President Trump has recently indicated – will hit hard against the combined production of the European Union, especially in Germany, as it is highly dependent on world trade.

Compounding the problem, policy differences over the Iran deal threaten to deepen the trade dispute, with German officials having publicly stated that Germany will stay in the deal regardless of the U.S. withdrawal.

Former Greek Finance Minister Yanis Varoufakis has argued, however, that Trump has a significant upper hand, because the U.S. is the largest destination for German exports.

“When you (Germany) have such a large trade surplus, you’re exposed to the United States and to whatever the U.S. administration wants to do. To be more specific, there are about 4,800 German companies that are doing business in the United States. And their business is—the balance sheet is about $600 billion. That’s a lot of money,” said Varoufakis. “This combination is effectively rubbing Angela Merkel’s nose in her own helplessness to impose the European Union’s policies on Iran, because, effectively, German business turns around to the German government and says, ‘You cannot protect us from Trump. We’re going to pull out of Iran, and we’re going to do more business in the United States.’”

Peter Malmqvist, head analyst at the Swedish investment and trade firm Remium Nordic, stated in a recent internal analysis made available to Lima Charlie News that, “the German stock market has gone from growth of around 20 percent annual rate to zero in a few months. This is consistent with the Ifo index’s conclusions; it shows that it is the stock market reacting to uncertainty.”

Yet, Ifo’s Chief Economist Klaus Wohlrabe believes that the downturn is part of a normalisation of the German economy and he warned against over-interpreting short-term fluctuations in the index he compiles on a monthly basis:

“I’m not worried. This is a normalisation. We have had very good economic data, and then it is natural that the numbers are a bit lower now. For the past five months, the Ifo index has gone down, but from a very high level. When one reaches a record, one must have some drop afterwards.” (German translation by article author).

As such, Herr Wohlrabe expects to see a German GDP decline from the 2.5 percent point of 2017 to a 2.2 percent point for 2018.

[Main Image: German Chancellor Angela Merkel sneezes as she and Russian President Vladimir Putin attend the Petersburg Dialogue at the Kurhaus resort in Wiesbaden, Germany. Photo: Anja Niedringhaus/AP]

John Sjoholm, LIMA CHARLIE NEWS

John Sjoholm is Lima Charlie’s Middle East Bureau Chief, Managing Editor, and founder of the consulting firm Erudite Group. A seasoned expert on Middle East and North Africa matters, he has a background in security contracting and has served as a geopolitical advisor to regional leaders. He was educated in religion and languages in Sana’a, Yemen, and Cairo, Egypt, and has lived in the region since 2005, contributing to numerous Western-supported stabilisation projects. He currently resides in Jordan. Follow John on Twitter @JohnSjoholmLC

Lima Charlie provides global news, insight & analysis by military veterans and service members Worldwide.

For up-to-date news, please follow us on twitter at @LimaCharlieNews

In case you missed it:

![Image Gesundheit! Europe's strongest economy suffers from a bit of an economic influenza [Lima Charlie News][Image: Anja Niedringhaus/AP]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/Gesundheit-Europes-strongest-economy-suffers-from-a-bit-of-an-economic-influenza.jpg)

![Africa’s Elections | In Malawi, food, land, corruption dominate [Lima Charlie News]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/Malawi-election-Food-land-corruption-480x384.jpg)

![Syria’s oil, gas and water - the Immiscible Solution to the War in Syria [Lima Charlie News][Photo: ANDREE KAISER / MCT]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/Syria’s-oil-gas-and-water-480x384.png)

![Image The Rwandan Jewel - Peacekeepers, Conflict Minerals and Lots of Foreign Aid [Lima Charlie World]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/Rwanda-Jewel-480x384.jpg)

![Image Russia's energy divides Europe [Lima Charlie News]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/Russias-energy-divides-Europe-Lima-Charlie-News-480x384.png)