Avoiding the Mistakes of the Past: How Trump can overcome the Shortcomings of Clinton’s 1994 Agreement with North Korea.

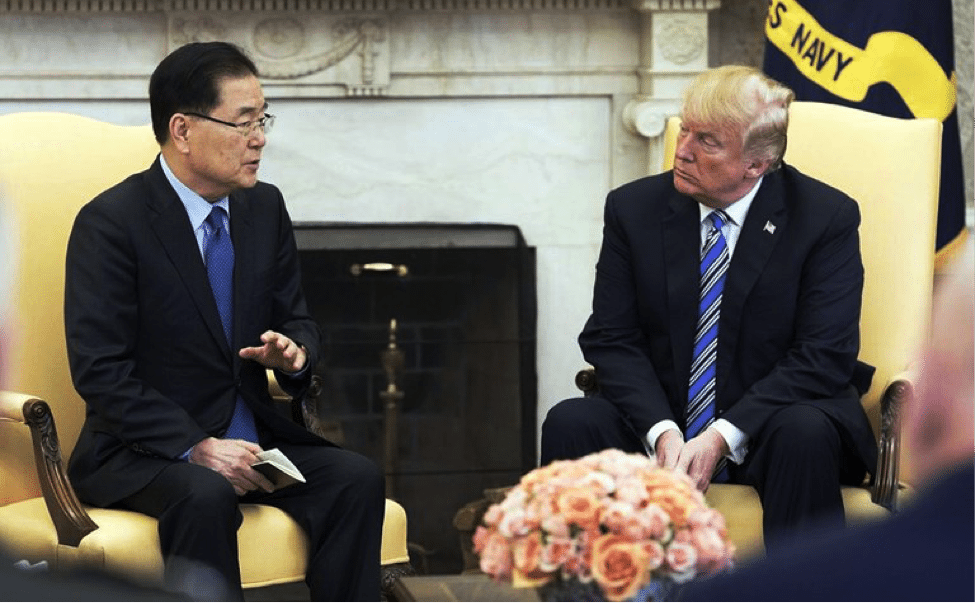

On March 8th, President Trump made history by accepting an invitation to join the North Korean autocrat, Kim Jong-un, for a summit to discuss the possibility of denuclearizing the Korean peninsula. The decision to meet with the regime’s leader, an unprecedented move for an American president, purportedly came as a surprise not only to Chung Eui-yong, the South Korean envoy who personally delivered the message but to President Trump’s national security advisors as well. In the days since the decision was made public, the American media has speculated on many aspects of the purposed summit, including the potential risks, rewards and the apparent haste with which the decision was made.

Make no mistake, the stakes couldn’t possibly be higher. Just last May, US Secretary of Defense, General James Mattis candidly explained that “a conflict in North Korea … would be probably the worst kind of fighting in most people’s lifetimes.” The same sentiment was echoed by President Trump’s Chief of Staff, General John Kelly who warned that were Pyongyang’s capacities to continue to develop, he would hope for a diplomatic solution. Since General Kelly gave that warning North Korea has allegedly completed its nuclear tests, with the official Korean Central News Agency announcing that it was now capable of “carrying [a] super-heavy [nuclear] warhead and hitting the whole mainland of the U.S.”

One critical issue which seems to be missing from the ongoing national dialog is why the last round of negotiations, which produced the 1994 Framework Agreement, failed to produce lasting results and what can be learned from the abortive agreement to improve the chance of success this time.

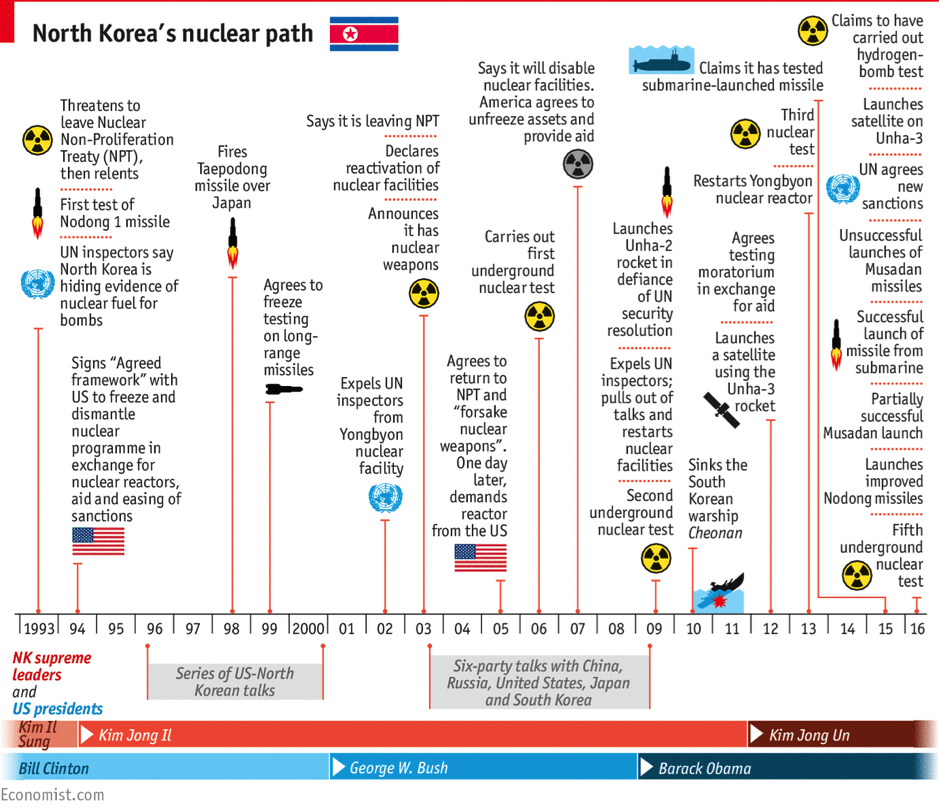

Let’s step back as the context is crucial in understanding how the last agreement failed so spectacularly. Despite North Korea’s current crushing poverty, it has historically maintained a fairly advanced nuclear weapons program, thanks in large part to the generous patronage the Soviet Union and the Cold War context in which the program was developed. Yet, Soviet technical assistance was not the only factor which propelled the North Korean nuclear program. One of the tenets of the state’s ideology, Juche, also played a pivotal role in the regime’s drive towards nuclearization. While more nuanced than can be explained in this article, the concept can be approximated as a determination to maintain self-reliance and is better understood when one considers Korea’s long and brutal colonial legacy. In fact, adherence to Juche was so central to North Korean ideology that the regime was only willing to sign on to the Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) in 1985 after immense international pressure and an agreement in which the USSR agreed to assist the regime in the construction of four light water reactors which would have greatly enhanced the nuclear program’s self-sufficiency.

However, by October 1991, the USSR was imploding and President George H.W. Bush decided to unilaterally withdraw a significant number of tactical nuclear weapons including those based in South Korea. This move was welcomed and reciprocated by Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev initiating a process in which North Korea saw its primary benefactor withdraw both military and economic support. Politically isolated and economically imperiled, the regime, which was believed to be in the early stages of constructing a nuclear weapon, seemingly acquiesced to international demands and signed the Joint Declaration on the Denuclearization of the Korean Peninsula with its southern counterpart. In signing the declaration both sides agreed to “not test, manufacture, produce, receive, possess, store, deploy or use nuclear weapons.”

The goodwill generated by the declaration quickly gave way to suspicion. In joining the NPT, North Korea agreed to a partial acceptance of the International Atomic Energy Agency’s (IAEA) Safeguard Agreement which typically grants the IAEA’s inspectors unrestricted access to all nuclear facilities. Under the agreement, the regime was also meant to provide the agency with a comprehensive declaration of all its nuclear material and related facilities. Neither of these conditions were met, as IAEA inspectors were barred from certain locations and suspected the declaration was not produced in good faith. The situation quickly escalated as the Clinton administration believed the regime had ferreted away enough plutonium to build a bomb and threatened economic sanctions in retaliation. The bellicose regime, not to be outdone, threatened war in response.

In a somewhat unexpected move, former President Carter, who had built a level of personal rapport with members of the regime, stepped in to defuse the tension. Carter’s efforts brought the North Koreans back to negotiations and ultimately helped produce a comprehensive agreement known as the Agreed Framework which was signed on October 21, 1994. The agreement included several components:

- Both parties reaffirmed their commitment to achieving a peaceful and nuclear-free Korean Peninsula, with the U.S. offering formal assurances against the use of nuclear weapons against the regime.

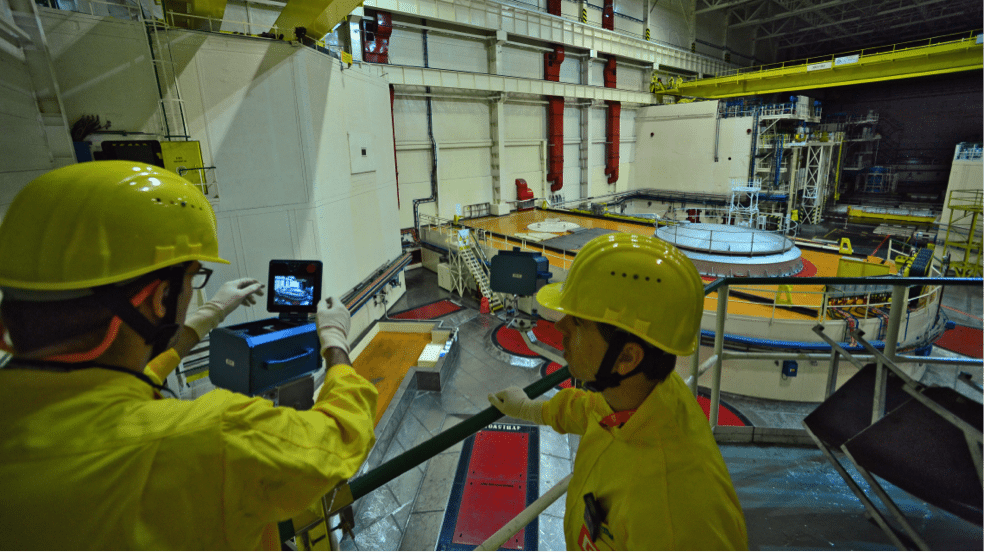

- The parties agreed to replace the regime’s gas-graphite moderated reactors with light-water reactors which was critical for both sides. Light-water reactors are significantly more fuel efficient which would be a benefit to North Korea as it claimed its energy needs were the primary driver behind its nuclear program. Yet, these reactors were also in the U.S.’s interests as they were the most proliferation-resistant type of reactor, producing significantly less plutonium and making the extraction of that plutonium near impossible to conceal from IAEA inspectors.

- The U.S. was obliged to lead an international consortium to finance and construct the new reactors with the capacity to generate 2,000 MW of electricity by 2003. The regime agreed to suspend operations at the existing gas-graphite reactors, including an operational 5 MW reactor (which had been completed in 1986) and halt construction on the 50 MW reactor and the Taecheon 200 MW reactor while the U.S. would provide up to 500,000 tons of oil annually to supplement the loss of energy.

- Upon the completion of the new light-water reactors, the regime agreed to dismantle all gas-graphite reactors. The two sides agreed to cooperate in finding a safe storage method for the spent fuel from the regime’s 5 MW reactor to prevent it from being used to make plutonium. The regime also agreed to allow for verification of its initial declaration to the IAEA, full cooperation with the IAEA’s inspections including the safeguard measures during the implementation of the agreement for existing reactors and the proposed reactors and to remain a party to the NPT.

- Finally, the parties agreed to enhance bilateral relations, reduce barriers to trade and investment and move towards full normalization of political and economic relations.

Given the current state of affairs between North Korea and the U.S., it shouldn’t come as a surprise that the agreement fell apart with both parties expressing grievances about the deal. The North Koreans essentially had two significant issues. First, the international consortium that proposed to finance and construct the new light-water reactors, the Korean Peninsula Energy Development Organization (KEDO), faced immense financing and manpower issues, habitual delays and only managed to commence construction in 2002 – a year before their agreed upon completion. Second, the regime claimed the commitments to normalize political and economic relations were never met.

The U.S. also had several issues with the agreement. Most glaringly, the IAEA was never able to completely verify the regime’s initial declaration, nor completely implement all of the safeguard measures. To make matters worse, the CIA began suspecting the regime of pursuing a different method of weaponizing its fissile material. Whereas previous efforts had focused on reprocessing spent fuel in order to create plutonium, the CIA believed the regime was now attempting a more technically advanced method of enriching uranium through the use of centrifuges. While the agreement was always controversial in the U.S., it meet a swift and arguably justifiable demise under the Bush Administration.

![Image George W. Bush meets with South Korean President Kim Dae Jung March 07, 2001 [AFP PHOTO/Luke FRAZZA]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/51590483.jpg)

The people’s army should always maintain a highly agitated state and be equipped with full fighting readiness so as to smash the enemies with a single stroke if they make the slightest move and achieve the historic cause of the fatherland’s reunification.

– Kim Jong-Un

The Agreed Framework was fundamentally flawed. As President Trump now considers new negotiations with North Korea he would do well to learn from the mistakes that were the agreement’s undoing.

The regime had two major grievances with the agreement. The first to arise was the substantial delay in the actual construction of the light-water reactors. To understand how this process was delayed, it best to look to the actual text of the agreement:

- The U.S. will organize under its leadership an international consortium to finance and supply the LWR [light-water reactor] project to be provided to the D.P.R.K. [Democratic People’s Republic of Korea]. The U.S., representing the international consortium, will serve as the principal point of contact with the D.P.R.K. for the LWR project.

- The U.S., representing the consortium, will make best efforts to secure the conclusion of a supply contract with the D.P.R.K. within six months of the date of this Document for the provision of the LWR project. Contract talks will begin as soon as possible after the date of this Document.

The language used in the agreement was extremely vague. There was no reference to the international partners who were meant to help finance and construct these new reactors. There was no reference to the financial commitments of each party involved in the construction. There was no mechanism to enforce the construction in a timely fashion, nor to resolve disputes which could have arisen from the construction process. Without establishing parameters and guidelines to see the project from start to conclusion, it is understandable why the regime became frustrated with the agreement.

Considering the regime’s second contention, that the commitments to normalize political and economic relations were never met, again we should revisit the text.

- The two sides will move toward full normalization of political and economic relations.

- Within three months of the date of this Document, both sides will reduce barriers to trade and investment, including restrictions on telecommunications services and financial transactions.

It is clear that both contentions arose from leaving the commitments undefined. While the regime believed relations would start to normalize within the mentioned three-month timeframe, U.S. officials believed the normalization of relations would follow a continuum, and as their security concerns were alleviated, political and economic relations would improve.

Yet, the U.S. had major problems with the agreement as well. The regime’s most obvious violation, failing to cooperate with the IAEA to verify its initial declaration, clearly violates the agreement’s following provision:

- The D.P.R.K. will remain a party to the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT) and will allow implementation of its safeguards agreement under the Treaty.

If that weren’t enough, the regime’s covert creation of a uranium enrichment program went against the very objective of the agreement, “to achieve peace and security on a nuclear-free Korean Peninsula,” as civilian nuclear reactors used for energy production do not require such highly enriched uranium. In reality, the only purpose such concentrated levels of enriched uranium can serve is to create a nuclear weapon.

Again, the vague nature of the agreement did not help the situation. The U.S. negotiators failed to establish the consequences of violating the agreement, leaving the Clinton Administration rudderless when violations became obvious and prompting the Bush Administration to terminate the ineffective agreement.

The agreement also suffered from ambiguous language that failed to outline the consequences if either party did not live up to its commitments. With the agreement being four pages long, perhaps that was inevitable. However, it also failed to engage the international community. As a bilateral agreement, it was only the U.S. which was obligated to act when it saw the agreement being violated. This seems to have been an oversight, because even as the U.S. was threatening punitive military action, violating the agreement did nothing to disrupt the economic relationships with China or South Korea, on which the regime had become heavily reliant.

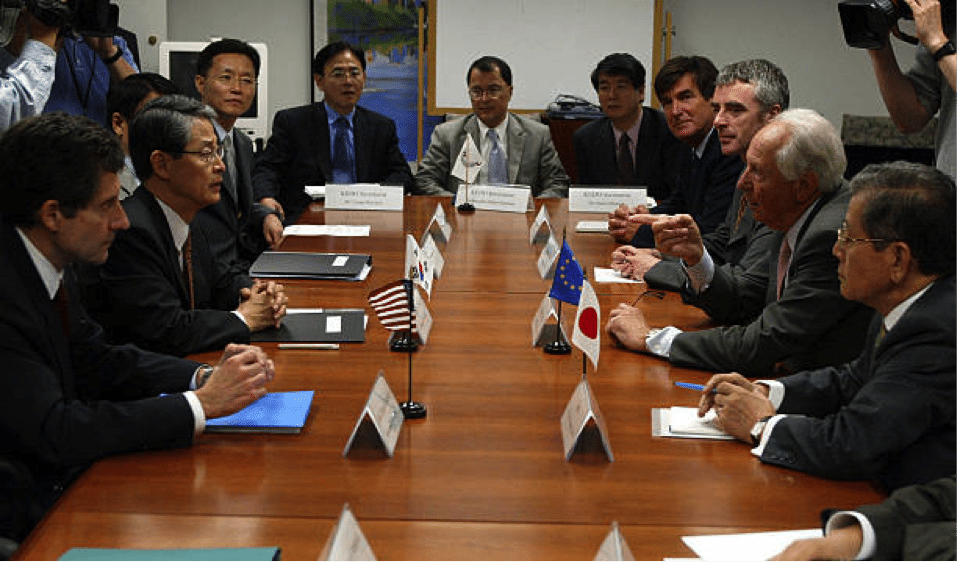

Considering this disastrous agreement, there are a few key points President Trump and his negotiators should keep in mind. While President Trump has a clear preference for bilateral agreements, North Korea’s nuclear weapons have become a global problem and negotiations need to include all relevant regional parties. Without regional consent, any effort to curtail the regime’s nuclear program can be undermined, with Russia’s lax enforcement of the international sanctions being a prime example. While China has a key role to play in the negotiations, so does Russia, Japan and South Korea if a new agreement is to be successful.

Another point to consider are the details. President Trump has been critiqued as being light on policy details. Under the Framework Agreement, the U.S. negotiators had focused primarily on preventing North Korea from accumulating enough plutonium to make a nuclear weapon. By not been detailed in the agreement, the regime simply set its sights higher and began working towards a more sophisticated enriched-uranium weapon. The move was a clear violation of the spirit of the agreement but didn’t violate the agreement’s technical aspects.

As President Trump prepares for the negotiations it would serve him well to assemble a team of the best nuclear scientists and disarmament experts available to address the technical aspects of the agreement.

The decision to negotiate with Kim Jong-un was an unprecedented and wise decision, but this summit will still be a high-risk, high-reward situation. The summit holds the potential to move the Korean peninsula towards denuclearization and reduce the dangerous hostilities that have built up over the decades between North Korea and the U.S.

But only if President Trump can learn from the mistakes of his predecessors.

LIMA CHARLIE NEWS, with Sean McNicholas

Global news, featuring insight & analysis by military veterans, intelligence professionals and foreign policy experts Worldwide.

For up-to-date news, please follow us on twitter at @LimaCharlieNews

In case you missed it:

![Image North Korea mistakes: how Trump can overcome the shortcomings of Clinton’s 1994 Agreement [Lima Charlie News]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/North-Korea-mistakes-how-Trump-can-overcome-the-shortcomings-of-Clinton’s-1994-Agreement.png)

![Image Sweden provides ‘quiet diplomacy’ for U.S. – North Korea talks [Lima Charlie News][Image: REUTERS / Janerik Henriksson]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/Sweden-U.S.-–-North-Korea-talks.jpg)

![Image Korea: Is Trump Bringing Peace in Our Time? [Lima Charlie News]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/Korea-Is-Trump-Bringing-Peace-in-Our-Time-480x384.png)

![Image Memorial Day may soon be a remembrance of democracy and those who had the courage to defend it [Lima Charlie News]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/Memorial-Day-may-soon-be-a-remembrance-of-democracy-and-those-who-had-the-courage-to-defend-it-Lima-Charlie-News-480x384.png)

![The Mind of Bolton - AUMF and the New Iran War [Lima Charlie News]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/Inside-the-mind-of-Bolton-Lima-Charlie-News-main-01-480x384.png)