Since 1949 NATO has been the cornerstone of Europe’s security. Amid tensions with Russia at a new high, NATO members have committed to spending more on defense, for which President Trump’s strong rhetoric deserves credit. But just who is supposed to ‘pay’ what to NATO?

In many ways the North Atlantic Treaty Organization could be considered one of the more complex, and frankly baffling, international organizations. Chartered in 1949, NATO has grown to include 29 member-countries. It is expensive, with an estimate reaching nearly $957 billion* in total defense spending for 2017. And as President Trump has been saying, the lion’s share of that total, 72% or a whopping $685 billion of the total defense expenditure came from the United States.

![Image [NATO Secretary-General Jens Stoltenberg and President Trump, July 11th, 2018, NATO Summit in Brussels][Photograph: Kevin Lamarque / Reuters]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/NATO-Summit-JULY-11-2018.jpg)

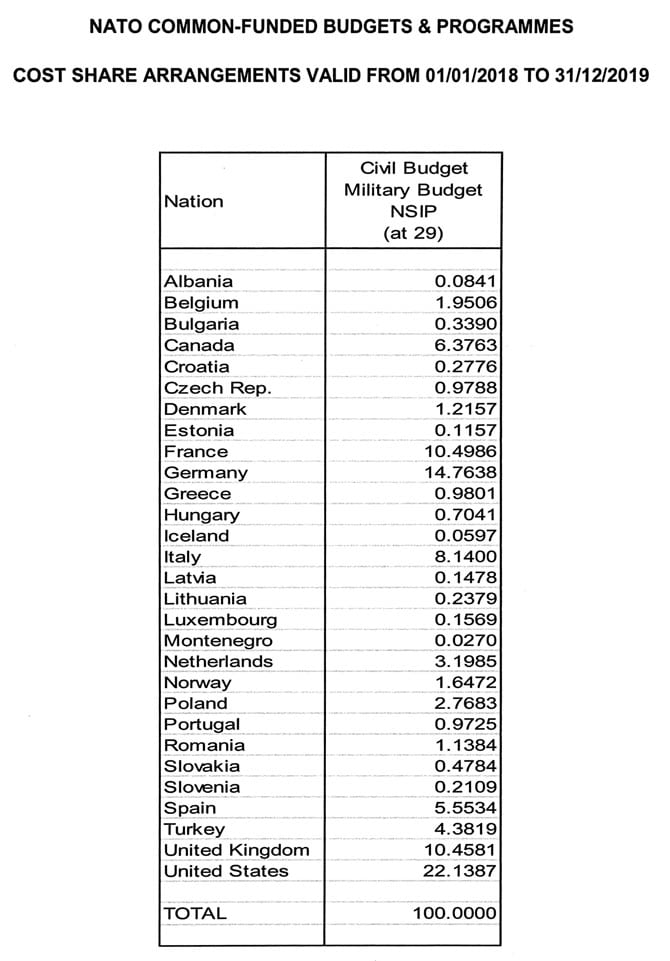

Direct contributions are used for collective defense initiatives like NATO-wide air defense or command and control systems (C2). These costs are financed through an agreed upon cost-share formula, based on Gross National Income (GNI). The United States still contributes the most. However, contextually American economic heft lends a degree of proportionality when considered in comparison to smaller member states. Despite President Trump’s previous claims, there is no evidence to support the notion that any member state is behind on these payments.

![Image chart [NATO Breakdown of Direct Contributions as of 2017]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/NATO-Contributions.jpg)

To highlight this fact, one must only consider the International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) created to restore security in Afghanistan. NATO agreed to take command of the force on August 11th, 2003. A decade later, the force numbered more than 87,000 strong, of which the United States contributed 60,000 troops, the United Kingdom contributed 7,700 troops and Iceland contributed just three troops.

Given the vast superiority of the United States Armed Forces, the United States’ ability to contribute to NATO operations far exceeds that of its allies.

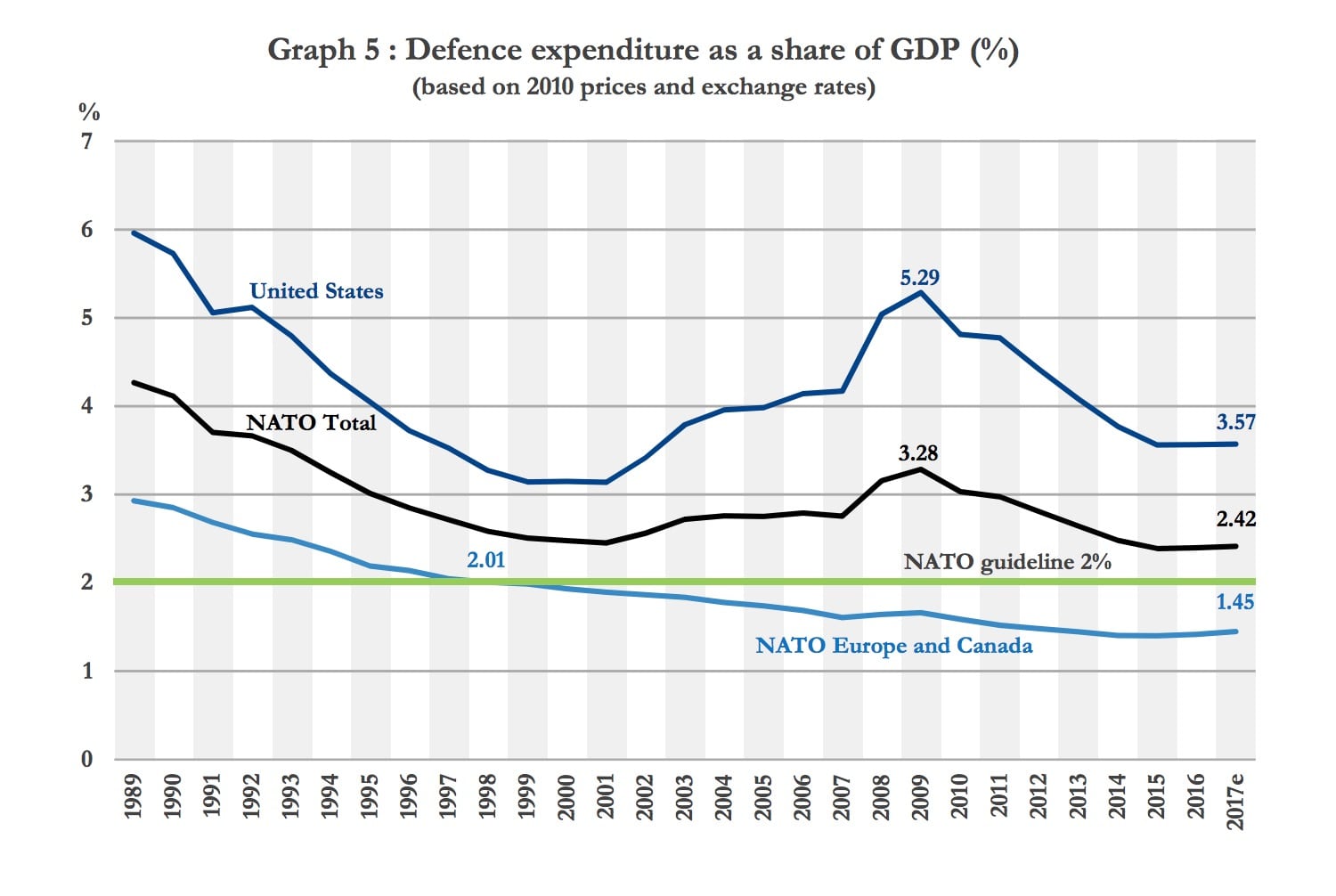

Yet, this discrepancy in military strength and the associated financial burden has led previous U.S. Presidents including John F. Kennedy, George W. Bush and Barack Obama to all similarly urge NATO members to commit more to their defense spending.

- “halt any decline in defence expenditure;

- aim to increase defence expenditure in real terms as GDP grows;

- aim to move towards the 2% guideline within a decade with a view to meeting their NATO Capability Targets and filling NATO’s capability shortfalls.”

But contention remains. President Trump had at one point made a shocking demand that NATO members increase defense spending to 4% of GDP. This would be a daunting task, given that even the United States, which outpaces all other members in defense spending, has yet to reach this target.

I had a great meeting with NATO. They have paid $33 Billion more and will pay hundreds of Billions of Dollars more in the future, only because of me. NATO was weak, but now it is strong again (bad for Russia). The media only says I was rude to leaders, never mentions the money!

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) July 17, 2018

In the aftermath of the summit, it remains unclear if additional increases to defense spending have been agreed upon. President Trump and French President Macron have made contradictory statements on the matter. While specific details remain elusive, the topic of contributions to the NATO alliance is sure to arise again.

[Main photo: Matt Dunham / AFP]

LIMA CHARLIE NEWS, by Sean McNicholas

Lima Charlie provides global news, featuring insight & analysis by military veterans and service members Worldwide.

For up-to-date news, please follow us on twitter at @LimaCharlieNews

In case you missed it:

![Image Blindspot on a Bureaucracy: Who’s supposed to 'pay' what to NATO? [Lima Charlie News][Photo: Matt Dunham / AFP]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/The-Public’s-Blindspot-on-a-Bureaucracy-Who’s-supposed-to-pay-what-to-NATO.png)

![Blossoming Russo-Turkish alliance leaves U.S., NATO behind [Lima Charlie News]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/Russia-Turkey-alliance-leaves-U.S.-NATO-behind-480x384.png)

![Image Russia and China’s 'hybrid warfare' - Does the West even care? [Lima Charlie News]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/Russia-China-Hybrid-Warfare-02-480x384.png)

![image NATO’s value can’t be measured in nickels and dimes [Lima Charlie News]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/NATO-Trump-0005-480x384.png)

![Blossoming Russo-Turkish alliance leaves U.S., NATO behind [Lima Charlie News]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/Russia-Turkey-alliance-leaves-U.S.-NATO-behind-150x100.png)

![Image Russia and China’s 'hybrid warfare' - Does the West even care? [Lima Charlie News]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/Russia-China-Hybrid-Warfare-02-150x100.png)