Drought and China’s economic downturn contribute to devastation in East Africa.

Yemen and the Horn of Africa are a widening gyre of civil strife, drought, economic downturn and famine. The region’s last famine killed 260,000 in 2011. Then, mostly Somali elderly and children died. This time, devastation is already regional and far more violent. Anticipating the worst humanitarian crisis in 60 years, the UN is hastening to raise billions of dollars to mitigate the crisis. However, treating the symptoms does little to stanch the global causes of the region’s calamity.

The catastrophe is indeed “humanitarian.” Yet, the characterization fails to convey the confluence of trends that continually transfer the developed world’s ills to less fortunate parts of the planet.

Following the deaths of those quarter million people, concentrations of carbon dioxide, the major cause of global warming, increased at their fastest rate for 30 years in 2013, according to the World Meteorological Organisation (WMO). Methane and nitrous oxide too rose. This pattern continued despite scientists’ warnings of the need to cut greenhouse gas emissions to halt global warming. The major emissions aren’t African.

Water

East Africa is almost entirely dependent on monsoons for rainfall. Monsoon season is twice annually, and if rain fails in either season, East Africa must wait most of a year for rain. A failed monsoon season precipitated the 2011 famine, and rain failed again during October and November last year.

Monsoon weather systems move clockwise around the Arabian Sea, a part of the western Indian Ocean. High water temperatures in the ocean, a reflection of global warming, can cause monsoons to release most or all of their rain over the ocean, before the storms make landfall.

Recent years have seen increasing sea temperatures. The October 2016 failure was caused by a negative “Indian Ocean Dipole” (IOD). A negative IOD is cooler-than-average waters in the western Indian Ocean, and warmer than average waters in the eastern Indian Ocean. So the precipitation occurred over the eastern Indian Ocean in Southeast Asia instead of over land in the Horn of Africa.

And when the weather fails, what does it mean for the people?

The UN is documenting the crisis in a series of reports on countries across the Horn of Africa. The most recent asserted that 1.4 million Somali children will suffer from acute malnutrition, that 275,000 of those cases will be life threatening. This UN report is just a snapshot of the disaster rolling through several economically and environmentally interlocked countries.

Geographically, these areas are all close enough together to suffer from the failed monsoon rains in October, but there is another common factor at work: economics.

China and the Economic Effect

East African economies are relatively undeveloped, so large portions of their exports consist of raw materials, commodities such as agricultural goods and resources derived of extractive industries.

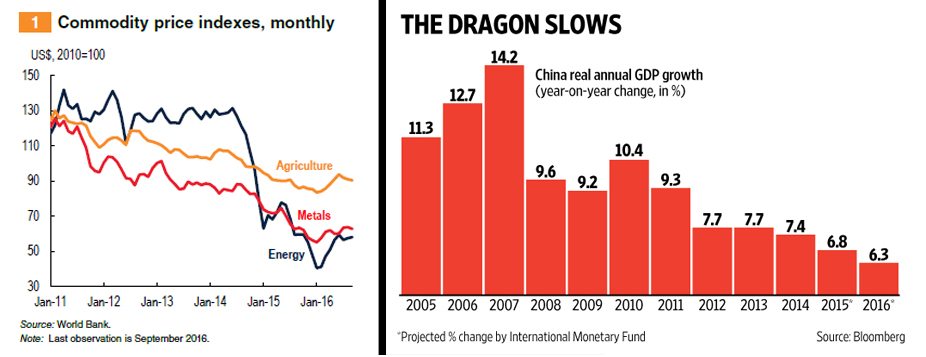

And here, China enters the picture. In order to develop into an industrial giant, the Chinese economy demanded a massive amount of raw materials. This created a massive boom in the value of these commodities worldwide. In recent years, however, as China’s annual growth rate has fallen out of the double digits, the value of raw materials slipped. It hit a 12-year-low last year.

These slipping commodity prices make commodity producers more desperate. Cattle are big business across East Africa, and cattle raiders are becoming increasingly heavily armed and deadly. Particularly in South Sudan, cattle raids have exacerbated ethnic tensions inflamed by the civil war.

Early in April, attacks by South Sudanese soldiers triggered a mass exodus to Uganda. Reports from upwards of 6,000 refugees described South Sudanese soldiers encircling a town, attacking immediately and indiscriminately. They lined up people on walls and shot them, gunning down civilians trying to flee the town. South Sudan’s civil war has a formal peace treaty, but horrendous ethnic violence and rape persist.

China’s slowing growth spells the end of an era for East Africa. In the past several years East African countries, excluding failed states, enjoyed relatively high growth rates, and not just because of the commodity boom driving up their growth rates.

With China’s rise generated enough capital to unleash a trillion dollar wave of investment across the globe. In Yemen, Ethiopia, Eritrea, Kenya and South Sudan, China’s economic growth translated into $26.6 billion in investment, according to the Heritage Foundation. To place that in GDP-relative context, China’s $1.2 billion investment in Yemen would translate into around $600 billion if it were introduced into the United States. And in large part, these investments came in the form of major infrastructure projects — highways, ports, and dams — infrastructure that would accelerate resource extraction, but also employed many people in the region.

Relative to the enormity of this still-recent influx of commercial capital from China, the international community’s present financial aid can’t help but appear meager. During an aid conference in Geneva two weeks ago, UN Secretary General António Guterres reminded delegates that 50 Yemeni children may have died while the delegates were speaking. There, donor countries pledged almost $1.1 billion — only half that the UN deemed necessary to respond to the famine in Yemen alone.

The UN and other aid groups continue to muster funds, but don’t appear to be capable of stopping what the UN is calling the largest humanitarian crisis since 1945. However, at least one country is taking a proactive approach to addressing the problem.

Ethiopia is a mountainous country, with rivers flowing into all of the neighboring countries. In 2006, a Chinese firm invested in a $1.6 billion Ethiopian dam project, and since then Ethiopia has partnered with China in multiple projects running into additional billions. Ethiopia pushed for massive dam projects on many of its rivers, including one on the Nile that will be the largest in Africa when it is completed. In addition to generating hydropower, the dams are designed to hydrate agriculture in the areas surrounding them. Ethiopia may be able to lean on these investments in the face of drought, and whether this will be to the detriment of countries downstream has been the subject of intense diplomatic contention. However, the tension may be worth the risk, because in areas this dry, a failure to manage water resources can be deadly.

There is an area outside of the monsoons’ reach on the UN’s list — the Lake Chad basin. Lake Chad, where Chad, Cameroon, Niger and Nigeria share borders, provides water to nearly 70 million landlocked people. The lake is increasingly salty and rapidly diminishing in size. Increased salinity is usually caused by agricultural and industrial run off, and it accelerates the rate at which water is absorbed into the ground. This is the one area on the U.N.’s list so underdeveloped that it is untouched by international economics.

Not so in East Africa.

East Africa relies on Chinese imports for inexpensive, moderately complex goods. For example, Ethiopia, a country 4000 miles away from China, depends on China for 33% of its imports, for manufactured goods such as textiles, trucks, prefabricated house, pesticides, and medicine.

However, as the people in the second largest economy grow richer, domestic Chinese consumers are starting to buy up more of China’s industrial product. China’s slowing growth and increasing domestic demand have led to price hikes for the developed world. According to the National Bureau of Statistics of China, the price of Chinese exports is up by nearly 13% over this time last year.

Increasing medical costs could take an immediate toll. PBS recently reported that preventable disease has killed more children in Yemen than violence from the war. Health officials are still working to prevent the re-emergence of polio, which was all but eradicated in 2009. Yemen is facing persistent drought, is in an ongoing war between the U.S.-backed government and the Houthi rebels, and is just one of the countries affected by the hunger crisis.

The 2011 tragedy might have registered globally as a terrifying warning about the impact of warming oceans on distant lands. Not until 2016 did the United States join the Paris Agreement on climate accord. Now following the 2016’s failed monsoon season, East Africa has neither China’s inflated commodity market for its raw materials nor China’s supply glut of cheap manufactured goods. The region has endured 5 more years of war, has seen slowed investment from China and the rest of the world, and has ever more strained water reserves.

The present United States Administration is seeking to withdraw from the climate accord, unfetter the coal industry and pipeline construction, and cut funding from the U.N. which houses several of the globe’s largest programs. In the short run, this leaves hope resting on the ability of the international community to raise and distribute relief money efficiently. In the long run, only a sustainable equilibrium of production and consumption in the developed world — for which we are all responsible — can mitigate the death toll from the cycles of weather and markets.

Diego Lynch, for LIMA CHARLIE NEWS

(THE UN, UNHCR, UN UNIVERSITY, WASHINGTON POST, DOWN TO EARTH, WORLD BANK, AND INDIAN EXPRESS CONTRIBUTED WITH INFORMATION TO THIS REPORT)

Lima Charlie provides global news, insight & analysis by military veterans and service members Worldwide.

For up-to-date news, please follow us on twitter at @LimaCharlieNews

![The Art of Foreign Influence: The Russian Military Adviser [Lima Charlie News]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/The-Art-of-Foreign-Influence-The-Russian-Military-Adviser-480x384.png)

](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/XBVUKTNZ5BHAJJOW22KSUJHS74-480x384.jpg)

![[Silver lining for China in Zimbabwe’s violent elections][Lima Charlie News]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/Screen-Shot-2018-08-02-at-12.51.35-PM-480x384.png)

![Africa’s Elections | In Malawi, food, land, corruption dominate [Lima Charlie News]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/Malawi-election-Food-land-corruption-480x384.jpg)

![Image The Rwandan Jewel - Peacekeepers, Conflict Minerals and Lots of Foreign Aid [Lima Charlie World]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/Rwanda-Jewel-480x384.jpg)

![Image [Women's Day Warriors - Africa's queens, rebels and freedom fighters][Lima Charlie News]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/Womens-Day-Warriors-Lima-Charlie-News-480x384.jpg)

![Image Zimbabwe’s Election - Is there a path ahead? [Lima Charlie News]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/Zimbabwe’s-Election-Is-there-a-path-ahead-Lima-Charlie-News-480x384.png)

![The Art of Foreign Influence: The Russian Military Adviser [Lima Charlie News]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/The-Art-of-Foreign-Influence-The-Russian-Military-Adviser-150x100.png)

](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/XBVUKTNZ5BHAJJOW22KSUJHS74-150x100.jpg)