Lima Charlie World is attending the Space Foundation’s Space Symposium in Colorado to discover how the world’s space agencies, military communities and tech companies are working together to tackle the Final Frontier.

We started Lima Charlie News with a mission to foster dialogue among military veterans from nations around the world. Over time this dialogue has expanded to include intelligence professionals and foreign policy experts as well. We’ve covered stories from around the globe about national security, foreign policy, geopolitics, cyber, tech, and our environment. Yet always, space – the Final Frontier – has captivated us all.

It’s no small coincidence that several of us here at Lima Charlie World are huge Star Trek fans. We carry an optimistic, idealistic, some would say naive view of mankind collaborating in the peaceful exploration of space, rather than in the conflict of space.

And so, it is with starry eyes that we report on the annual Space Symposium.

The Space Symposium is an annual conference for all things space – rockets, satellites, and other space exploration tools are unveiled to the public. Speakers this year, as every year, are a Who’s Who in the space, military and academic communities.

Of course there is a heavy presence of U.S. space and military establishment (which includes NASA, the U.S. Navy, Air Force, Air Force Space Command (AFSPC), the U.S. Army Space and Missile Defense Command / Army Forces Strategic Command (USASMDC/ARSTRAT), DoD and DOS, the new DoD Space Development Agency (SDA) and the re-established National Space Council). Of course there are major aerospace/defense contractors, such as Lockheed Martin, Northrop Grumman, Raytheon, Ball Aerospace, Boeing, and Booz Allen Hamilton.

But there is also a smorgasbord of representatives from space agencies and aerospace companies from around the world.

The Space Symposium is made possible through the efforts of the Space Foundation, a nonprofit organization founded in 1983 that is based out of Colorado Springs, Colorado. The Space Foundation seeks to “inspire, educate, connect, and advocate on behalf of the global space community.” This year will mark the 35th time the event has brought together leaders in the industry.

In addition to education and awareness, the Space Foundation sponsors various awards for achievement and innovation. These include the Space Achievement Award, the Douglas S. Morrow Public Outreach Award, and the Alan Shepard Technology in Education Award.

The Foundation’s highest honor, with nominations from the space industry worldwide, is named after retired U.S. Air Force General James E. Hill. The award recognizes “outstanding individuals who have distinguished themselves through lifetime contributions to the welfare or betterment of humankind through the exploration, development and use of space, or the use of space technology, information, themes or resources in academic, cultural, industrial or other pursuits of broad benefit to humanity.” Last year’s recipient was American aerospace engineer Christopher C. Kraft, Jr.

The dramatic orbiting of the first Sputnik by the Soviet Union on October 4, 1957 was like a spark that ignited and speeded the process of developing the exploration and peaceful uses of outer space on a continuing and larger scale.

– Eilene Galloway, Aerospace Pioneer / NASA Advisory Committee

Dogs, Monkeys and a Race to Space

On October 4, 1957, the USSR launched the world’s first artificial satellite, the 184 pound Sputnik-1.

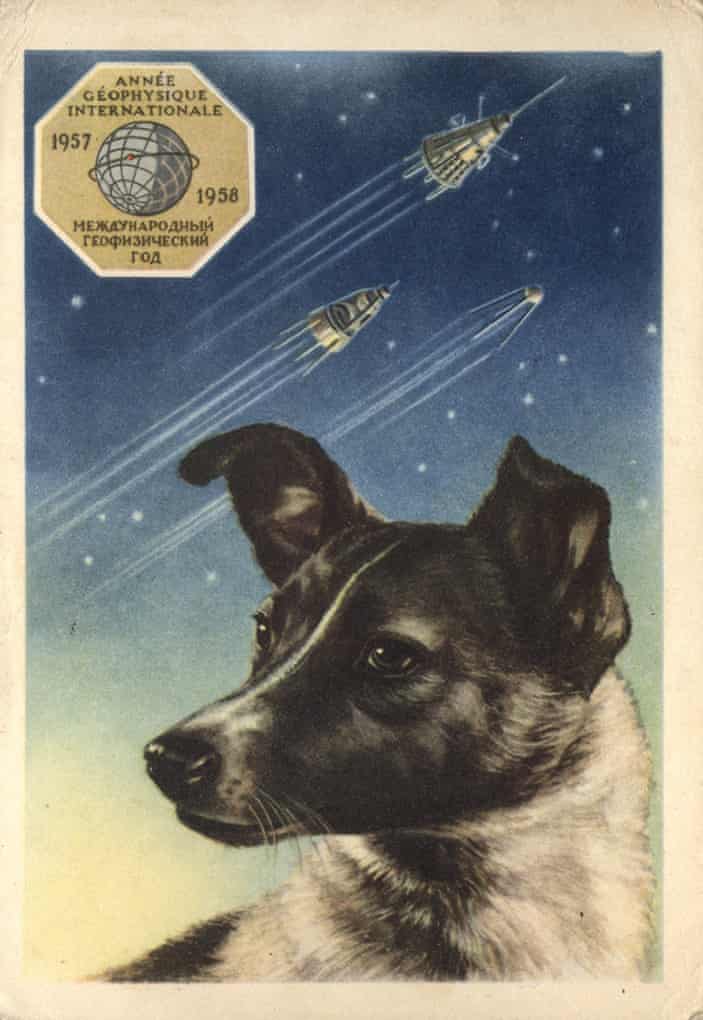

The Soviet Union would soon follow just 32 days later with the successful launch of Sputnik 2, a 500 kg, four meter high spacecraft that carried as its passenger a small female dog that, before her “training” had lived as a stray on the cold streets of Moscow. She would become known worldwide as Laika (Лайка), a Russian word for for several breeds of dogs. Yet, she had actually been called by Soviet scientists and mission specialists several names and nicknames, among them Kudryavka (Russian for Little Curly), Zhuchka (Little Bug), and Limonchik (Little Lemon). Laika would be among the first animals in space, and the first to orbit the Earth.

Since 1951, the Soviets had launched 12 dogs into sub-orbital space on ballistic flights aboard the Soviet R-1 series rockets in preparation for this orbital mission. The first sub-orbital astronauts, two dogs named Dezik and Tsygan (“Gypsy”), had been successfully launched and retrieved six years before Laika’s Sputnik 2 launch. They were followed by a second launch one month later, but the dogs Dezik and Lisa did not survive.

By the third launch, one of the dogs chosen, Smelaya (“Bold”), was more the wiser. She ran away the day before the launch. With the crew worried that wolves living nearby would eat her, she returned a day later and the test flight resumed successfully. A fourth and fifth launch would follow, with one success and one failure. Just before the sixth flight on September 15, 1951, one of the two dogs, Bobik, escaped and a replacement was found near the local canteen. She was given the name ZIB, the Russian acronym for “Substitute for Missing Dog Bobik.” Both dogs reached 100 kilometers and returned successfully.

Other dogs associated with this series of flights included Albina (“Whitey”), Dymka (“Smoky”), Modnista (“Fashionable”), and Kozyavka (“Gnat”).

Throughout 1951 and 1952, the U.S. would successfully launch a monkey named Yorick and 11 mice in an Aerobee missile, followed by two Philippine monkeys, Patricia and Mike, which were the first primates to reach a high altitude of 36 miles. Patricia and Mike would be recovered safely by parachute.

Laika’s 1957 Sputnik 2 flight was hailed by Nikita Khrushchev and the Soviets as a “space spectacular” mission that proved Soviet superiority in space. Immediately after the November 3, 1957 launch a fascination with Laika and her journey captivated millions worldwide, including Sputnik watchers in America.

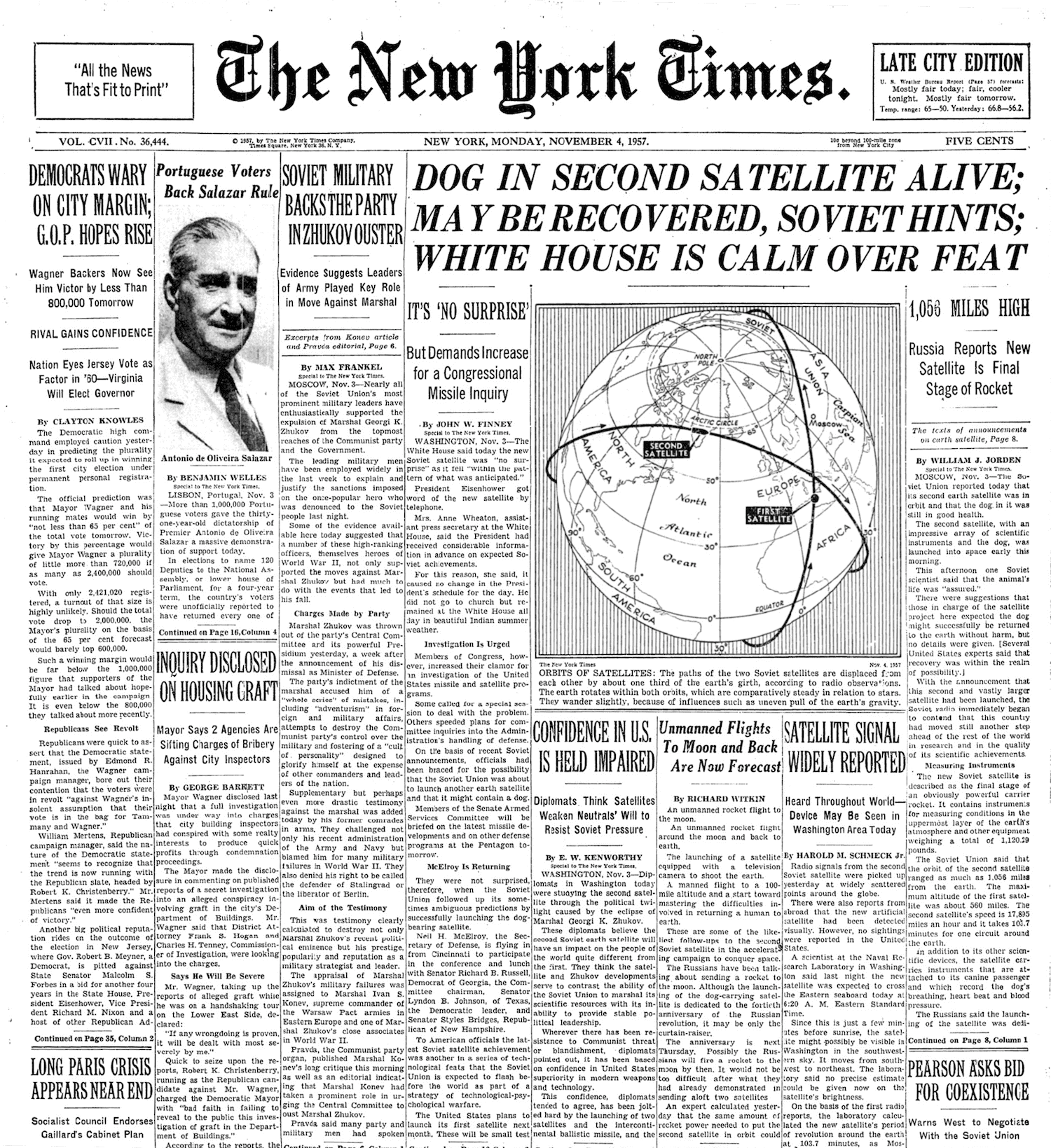

It was widely reported by the Soviets that the mission was a success; Soviet scientists continued to receive telemetry signals of Laika’s physiological reactions, reporting that she was alive and well days after launch. Yet, by November 6, 1957, the Associated Press reported, “The Soviet satellite appeared to be tumbling end over end. This caused renewed speculation about the fate of Laika, the little Russian dog harnessed inside.” It added, “Soviet scientists indicated several days ago that eccentric movements of the satellite might in time cost the dog’s life.” By November 8, 1957, the NY Times ran the headline, “Condition of Dog Is Now In Doubt,” reporting that Soviet scientists had “suddenly broke off their regular reports on the condition of the dog.”

By November 11, Moscow issued a statement that Sputnik 2’s radio transmitters had ceased to function and that all medical and biological observations had been completed. By the next day Radio Moscow confirmed that Laika had died.

The Soviets would maintain that Laika did eventually die after a full six days when her oxygen ran out. It was also claimed that Laika had been euthanized prior to oxygen depletion. In fact, Laika had died only a few hours after launch due to extreme heat. This had been hinted at years later during a 1993 interview with Lieutenant General Oleg Gazenko, one of the leading scientists behind the Soviet animals in space program. It was later verified in 2002 by Sputnik 2 scientist Dimitri Malashenkov.

Sputnik 2 would continue to orbit the earth for 162 days, carrying the body of Laika, making 2,570 orbits, before visibly burning up on April 14, 1958.

The gesture thrown out by Khrushchev was not a gesture of defiance by one country of the East to one of the West. It was a challenge by the Communist world to the Free World.

-Paul-Henri Spaak, Second Secretary-General of NATO, speech before NATO, Oct. 30, 1957

The profound effects of the Sputnik 2 flight would fuel great fear and apprehension among America and her allies amid an ever heating up Cold War.

On November 3, 1957, the AP reported, “In announcing the launching of the first earth satellite ever put in a globe-circling orbit under man’s controls, the Soviet Union claimed a victory over the United States.” The article also reported that President Dwight D. Eisenhower, at an October 9th new conference, said of the military significance of Russia’s first satellite: “That does not raise my apprehension, not one iota.”

Despite Eisenhower’s assurances, paranoia continued. On November 5, 1957, the NY Times reported, “Scientists in many lands speculated yesterday that a Soviet rocket might already be en route to strike the moon with a hydrogen bomb in the midst of its eclipse Thursday.”

On November 6, 1957, Nikita Khrushchev, in a 15,000 word address before a special session of the Supreme Soviet, called for a top level conference of capitalist and communist countries that could prevent war and end the Cold War. He called for the establishment of peaceful competition, and urged the West to join Russia’s space efforts in a “commonwealth of sputniks.” According to the NY Times, however, Khrushchev, who was joined by Mao Tse-tung at the event commemorating the 40th anniversary of the Bolshevik revolution, “chided” the U.S. “for its slowness in putting an earth satellite into space.” Reportedly Khrushchev also “scoffed” at Americans “who said the United States never intended to race the Soviet Union into the skies with Earth satellites.”

Other American newspapers would also echo the impression with headlines such as “Khrushchev Ridicules Space Efforts Of U.S.” (which included a story that the “Reds” were developing “light speed rockets”), and “U.S. Taunted By Khrushchev Over Missiles.” The Associated Press reported, “Nikita Khrushchev and Mao Tse-tung made a double-barreled attack today on the United States, gibing at its lag on launching Sputniks and accusing it of plotting trouble all over the world.”

Amid President Eisenhower’s downplaying of the success of the Soviet space program, just days after Sputnik 2’s launch the President was presented with a 29 page report titled, “Deterrence & Survival in the Nuclear Age” (known as the Gaither Report). The report briefed him on the Soviet threat and its accelerating nuclear and ICBM development. It concluded that by 1959, “the USSR [would] be able to launch an attack with ICBMs carrying megaton warheads, against which SAC (Strategic Air Command) will be almost completely vulnerable under present programs.”

The Gaither Report suggested measures to “strengthen and defend the Free World.” This looming threat and the urgency to match and exceed Russia’s ballistic missile and satellite achievements was soon felt across America. On November 13, 1957, in an open letter to President Eisenhower, John S. Hayes, president of the Washington Post Broadcast Division asked the President to name the first U.S. space satellite “The Freedom Sphere.” This was immediately backed by four members of Congress.

Also in November, 1957, Congressional hearings, chaired by Senate Majority Leader Lyndon B. Johnson (D-TX) had begun to investigate and assess America’s resources for achieving superiority over the Soviets. According to Legislative Reference Service national defense analyst Eilene Galloway, “The hearings were conducted in an emergency atmosphere of deep concern with the status of U.S. national defense.” The hearings would continue into January 1958, recording 2,476 pages “of the facts essential for understanding the total situation as a basis for planning the future.”

Galloway’s final report outlined four potential options: (1) establish a new government agency; (2) assign the program to the Atomic Energy Commission; (3) establish the 43-year-old National Advisory Committee on Aeronautics (NACA) as the controlling agency; or (4) assign the space program to the Department of Defense’s Advanced Research Projects Agency.

One month later America’s space program would suffer a severe setback when, in December 1957, its first artificial satellite, Vanguard, exploded on the launch pad.

On April 2, 1958, in a special note sent to Congress, President Eisenhower called for a civilian space agency based on NACA. Twelve days later both the U.S. Senate and the House introduced versions of the NASA bill, H. R. 12575, the National Aeronautics and Space Act of 1958, with hearings beginning the next day.

On July 29, 1958, President Eisenhower signed the National Aeronautics and Space Act, establishing the National Aeronautics and Space Agency (NASA). NASA would officially begin operations on October 1, 1958, 61 years ago.

The Congress hereby declares that it is the policy of the United States that activities in space should be devoted to peaceful purposes for the benefit of all mankind.

– National Aeronautics and Space Act of 1958, Declaration of Policy and Purpose, Sec. 102(a)

Space Treaties, Space Force, and a Federation of Planets Countries

Today, there are over 70 countries with space agencies. These space agencies operate on a national and international level, often seeking cooperation with like-minded space agencies, governmental bodies, international organizations, private companies, universities, or research institutes. They often organize into regional organizations, or enter into cooperation agreements, treaties, implementing agreements, or memorandums of understanding (MOUs).

Amid the backdrop of the Space Race and the Cold War in the 1950s and 1960s, the United Nations emerged as the primary forum for the negotiation and crafting of the overall legal framework for cooperation in the peaceful exploration and use of outer space. This would include outlining such issues as the obligation to render assistance to astronauts, the identification of objects launched into space, both on a national basis and at the UN, and the assurance that the Moon would remain a part of the “common heritage of mankind.”

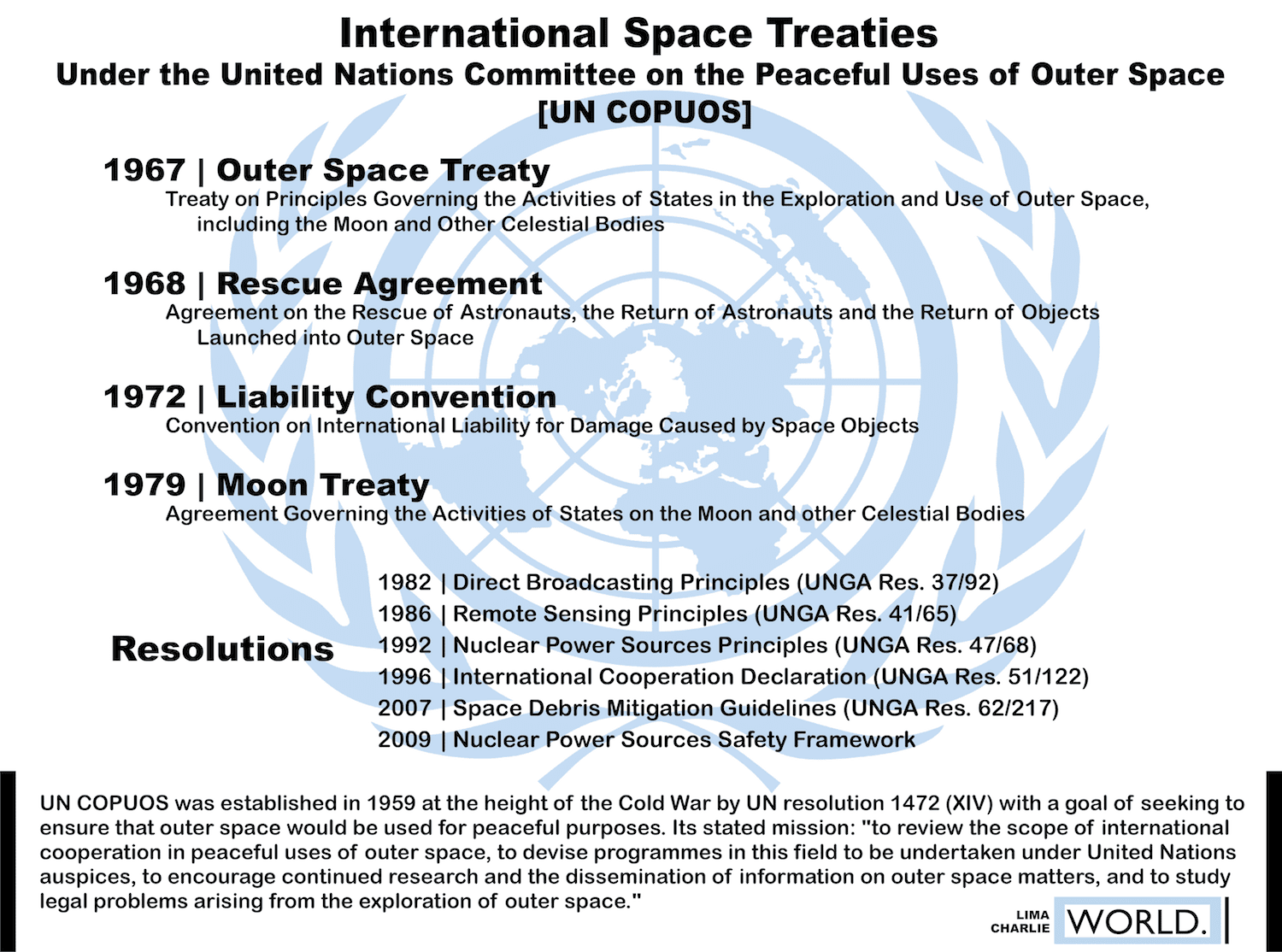

Shortly after the launch of Sputnik, on December 13, 1958, the United Nations Office for Outer Space Affairs (UNOOSA) was created as a small expert unit within the UN Secretariat in New York to assist the newly formed ad hoc Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space (COPUOS). It was established by UN resolution 1472 (XIV). The mission of COPUOS: “to review the scope of international cooperation in peaceful uses of outer space, to devise programmes in this field to be undertaken under United Nations auspices, to encourage continued research and the dissemination of information on outer space matters, and to study legal problems arising from the exploration of outer space.”

In September, 1960, in a speech before the UN’s General Assembly, President Eisenhower said:

“[W]ill outer space be preserved for peaceful use and developed for the benefit of all mankind? Or will it become another focus for the arms race–and thus an area of dangerous and sterile competition? The choice is urgent. And it is ours to make.”

Eisenhower continued:

“The nations of the world have recently united in declaring the continent of Antarctica ‘off limits’ to military preparations. We could extend this principle to an even more important sphere. National vested interests have not yet been developed in space or in celestial bodies. Barriers to agreement are now lower than they will ever be again. The opportunity may be fleeting. Before many years have passed, the point of no return may have passed.

Let us remind ourselves that we had a chance in 1946 to ensure that atomic energy be devoted exclusively to peaceful purposes. That chance was missed when the Soviet Union turned down the comprehensive plan submitted by the United States for placing atomic energy under international control. We must not lose the chance we still have to control the future of outer space.”

Eisenhower proposed four basic terms of agreement:

“1. We agree that celestial bodies are not subject to national appropriation by any claims of sovereignty.

2. We agree that the nations of the world shall not engage in warlike activities on these bodies.

3. We agree, subject to appropriate verification, that no nation will put into orbit or station in outer space weapons of mass destruction. All launchings of space craft should be verified in advance by the United Nations.

4. We press forward with a program of international cooperation for constructive peaceful uses of outer space under the United Nations. Better weather forecasting, improved world-wide communications, and more effective exploration not only of outer space but of our own earth-these are but a few of the benefits of such cooperation.”

According to President Eisenhower, “Agreement on these proposals would enable future generations to find peaceful and scientific progress, not another fearful dimension to the arms race, as they explore the universe. But armaments must also be controlled here on earth, if civilization is to be assured of survival. These efforts must extend both to conventional and non-conventional armaments.”

It would take six years of subsequent sessions of the General Assembly, considering declarations and resolutions, to address these issues before U.S. President Lyndon B. Johnson and Soviet Minister for Foreign Affairs A. A. Gromyko would begin to agree, in 1966, upon the space treaty’s basic principals.

The Outer Space Treaty (Treaty on Principles Governing the Activities of States in the Exploration and Use of Outer Space, including the Moon and Other Celestial Bodies) entered into force in October 1967. The treaty provides the basic framework on international space law, including the following principles:

- the exploration and use of outer space shall be carried out for the benefit and in the interests of all countries and shall be the province of all mankind;

- outer space shall be free for exploration and use by all States;

- outer space is not subject to national appropriation by claim of sovereignty, by means of use or occupation, or by any other means;

- States shall not place nuclear weapons or other weapons of mass destruction in orbit or on celestial bodies or station them in outer space in any other manner;

- the Moon and other celestial bodies shall be used exclusively for peaceful purposes;

- astronauts shall be regarded as the envoys of mankind;

- States shall be responsible for national space activities whether carried out by governmental or non-governmental entities;

- States shall be liable for damage caused by their space objects; and

- States shall avoid harmful contamination of space and celestial bodies.

The Outer Space Treaty was soon followed by the Rescue Agreement (1968)(Agreement on the Rescue of Astronauts, the Return of Astronauts and the Return of Objects Launched into Outer Space), the Liability Convention (1972)(Convention on International Liability for Damage Caused by Space Objects), and the Moon Treaty (1979)(Agreement Governing the Activities of States on the Moon and Other Celestial Bodies).

As of February 2019, 108 countries are parties to the Space Treaty, while another 23 have signed the treaty but have not completed ratification.

President Johnson would state that Article IV of the Space Treaty, the prohibition on placing nuclear weapons or other weapons of mass destruction in orbit, on celestial bodies, or “station them in outer space in any other manner,” would be “the most important arms control development since the 1963 treaty banning nuclear testing in the atmosphere, in space and under water.”

On Friday, December 9, 1966, the NY Times ran the headline:

TREATY TO BAR SPACE WAR BY EXCLUSION OF WEAPONS AGREED UPON AT THE U.N.

President Greets Accord As a Major Step to Peace

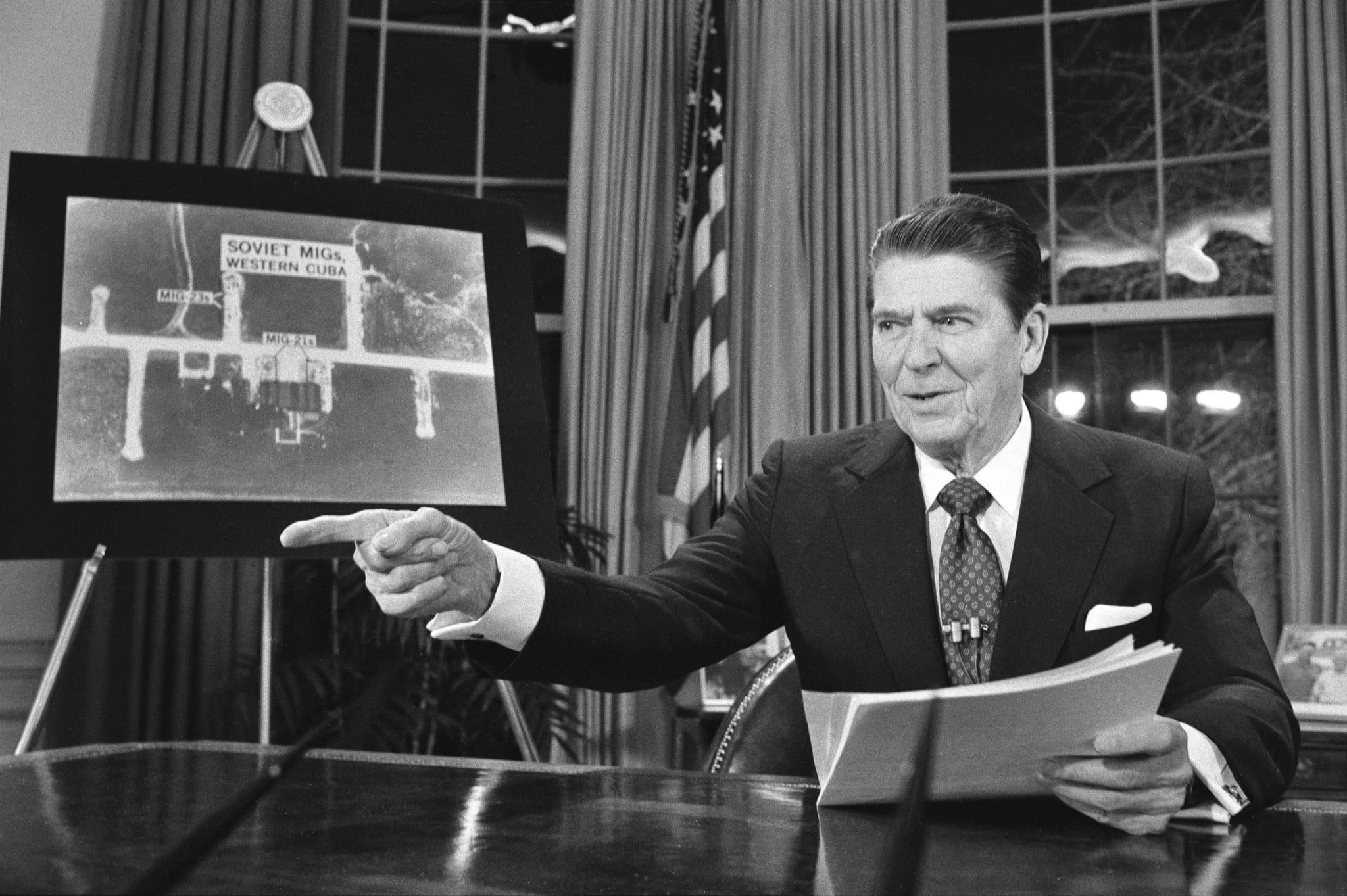

What if free people could live secure in the knowledge that their security did not rest upon the threat of instant U.S. retaliation to deter a Soviet attack, that we could intercept and destroy strategic ballistic missiles before they reached our own soil or that of our allies?

-President Ronald Reagan, March 23, 1983, Strategic Defense Initiative (“Star Wars”) speech

Since the Outer Space Treaty was ratified, it has been tested.

Questions arose about the prohibitions on weapons in space during the height of the US-USSR arms race. In the late 1950s, prior to the treaty’s ratification, the U.S. Air Force even considered detonating an atomic bomb on the Moon. Ostensibly for scientific research, the idea was generally considered as a display of U.S. superiority to the Soviet Union and the rest of the world. After a top secret study, code named Project A119, the idea was scrapped. A mission to the Moon via the Apollo program was considered much more persuasive, and much less antagonistic. A young graduate student named Carl Sagan had assisted with the study.

Among both the U.S. and Russian designs for anti-satellite weaponry, the Soviet’s 1970s space program included a 23-millimeter automatic “Space Cannon.” Mounted on the Salyut space station, such conventional weapons, however, don’t violate the treaty. With President Ronald Reagan’s announcement in 1983 of the Strategic Defense Initiative (SDI), dubbed the “Star Wars” defense system by Senator Ted Kennedy, the issue was once again raised. Various ideas that were considered for SDI included directed energy weapons (DEWs), such as a particle beam weapon, lasers, and plasma weapons. Also considered was a hypervelocity railgun and nuclear shaped charges.

In March 2018, when President Trump announced the creation of the Space Force during a speech at the Marine Corps Air Station Miramar in San Diego, California, he stated, “My new national strategy for space recognizes that space is a warfighting domain, just like the land, air, and sea.” A version of the president’s policy was first included in the 2019 NDAA, which created a “U.S. Space Command” when signed into law in August 2018. With President Trump’s signature of “Space Policy Directive 4” (SPD-4) on February 19, 2019, all uniformed and civilian personnel currently supporting space operations will funnel into the Space Force.

On March 26, 2019, at a meeting of the National Space Council, Vice President Mike Pence declared that American astronauts will walk on the moon again before the end of 2024 “by any means necessary.” Pence raised concerns about China and Russia, saying “We’re in a space race today, just as we were in the 1960s, and the stakes are even higher.”

“Under the President’s leadership, NASA will lead the way back to the moon,” Vice President Pence said, “starting with the construction of a Lunar Orbital Platform — the Gateway — which will provide a scientific outpost, supply center, and eventually a fuel depot, and will give our nation a strategic presence in the lunar domain.” Pence added, “From this orbiting platform, and with our international and commercial partners, American astronauts will return to the moon to explore its surface and learn how to harness its resources to launch expeditions to Mars.”

Since Vice President Pence made that announcement, on January 3, 2019, China’s space agency CNSA landed the Chang’e-4 lander and Yutu-2 rover on the far side (the “dark side”) of the Moon. By the end of 2019, China is expected to land its Chang’e-5 mission on the Moon and return regolith samples to Earth. China aims to launch a third space station into Earth’s orbit by 2022, to establish a manned lunar base before 2030, and to use that lunar base as a jumping off point for future trips to Mars.

While the Outer Space Treaty prohibits the use of “nuclear weapons or any other kinds of weapons of mass destruction” in space, the treaty also states:

“The Moon and other celestial bodies shall be used by all States Parties to the Treaty exclusively for peaceful purposes. The establishment of military bases, installations and fortifications, the testing of any type of weapons and the conduct of military maneuvers on celestial bodies shall be forbidden. The use of military personnel for scientific research or for any other peaceful purposes shall not be prohibited. The use of any equipment or facility necessary for peaceful exploration of the Moon or other celestial bodies shall also not be prohibited.” (Art. 4, Para. 2).

On November 25, 2015, President Barack Obama signed into law the Commercial Space Launch Competitiveness Act of 2015 (sometimes referred to as the Spurring Private Aerospace Competitiveness and Entrepreneurship (SPACE) Act of 2015). The SPACE Act explicitly allows U.S. citizens to “engage in the commercial exploration and exploitation of ‘space resources’ [including … water and minerals],” opening the door for U.S. companies to explore, extract, and recover space resources – otherwise known as “space mining.” Some scholars have argued that this recognition of the ownership of space resources violates the Outer Space Treaty.

Interestingly, the Moon Treaty has been considered a failure as it has not been ratified by the United States, most of the members of the European Space Agency, Russia or China. Currently only 18 countries are parties to the treaty. The Moon Treaty seeks to increase the obligations and prohibitions set forth in the Outer Space Treaty, by among other things, ensuring that the Moon must be used for the benefit of all mankind. For example, Article 3 states:

1. The moon shall be used by all States Parties exclusively for peaceful purposes.

2. Any threat or use of force or any other hostile act or threat of hostile act on the moon is prohibited. It is likewise prohibited to use the moon in order to commit any such act or to engage in any such threat in relation to the earth, the moon, spacecraft, the personnel of spacecraft or man-made space objects.

3. States Parties shall not place in orbit around or other trajectory to or around the moon objects carrying nuclear weapons or any other kinds of weapons of mass destruction or place or use such weapons on or in the moon.

4. The establishment of military bases, installations and fortifications, the testing of any type of weapons and the conduct of military manoeuvres on the moon shall be forbidden …

Article 4, dealing with scientific exploration, states, “The exploration and use of the moon shall be the province of all mankind and shall be carried out for the benefit and in the interests of all countries, irrespective of their degree of economic or scientific development.” In conjunction with Article 4, Article 11 states, in part:

1. The moon and its natural resources are the common heritage of mankind …

2. The moon is not subject to national appropriation by any claim of sovereignty, by means of use or occupation, or by any other means.

3. Neither the surface nor the subsurface of the moon, nor any part thereof or natural resources in place, shall become property of any State, international intergovernmental or non-governmental organization, national organization or non-governmental entity or of any natural person …

https://twitter.com/RusEmbUSA/status/1027789812382793728

The two biggest competitors to U.S. space dominance, Russia and China, have demonstrated surprising capabilities in recent years. In 2015, Russia reorganized its space forces under a distinct entity, Aerospace Forces. In the same year, China established the Strategic Support Force, which is responsible for space and cyber missions. China’s rise in the space domain came amid much fanfare when a successful 2007 anti-satellite missile test threw debris into orbit around Earth, endangering numerous other satellites. Subsequent tests, which produced no collateral debris, have attracted far less attention but have demonstrated Beijing’s increased capability in space.

Russia, meanwhile, has also entered a presumably grey area with its RS-28 Sarmat nuclear ICBM. While the U.S. State Department has recently condemned the development of the missile system as a violation of the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty, it did not allege a violation of the Outer Space Treaty. If considered a “Bombs in Orbit” weapon system, some believe the RS-28 Sarmat, may violate the Space Treaty.

Since 2015, the U.S., China and Russia have launched 15, 11 and 10 military-class payloads into orbit respectively. The European Space Agency (ESA), which charter stipulates that it should pursue space programs for “peaceful purposes” only, has launched only one, according to the FAA and Union of Concerned Scientists.

Todd Harrison, the Director of Aerospace Security at the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), who authored a Space Threat Assessment report published by CSIS last year, told Lima Charlie News that missiles are not the only threat to U.S. assets in orbit.

“[W]hat is actually more difficult to deal with is non-kinetic threats to space systems.” Lasers, jammers and spoofers can confuse and render useless both civil and military space systems. Moreover, these systems are “relatively inexpensive to produce and deploy in large numbers” and thus being widely proliferated. Russian systems are in use in Ukraine and Syria, with suspected proliferation in North Korea as well.

At last year’s Space Symposium, Lima Charlie News’ Don Martinez spoke with one of the leaders of the “Russian delegation,” cosmonaut Sergei Krikalev, who is also the Executive Director of Piloted Space Flights at ROSCOSMOS. Krikalev, who was first selected as a cosmonaut in 1985, and who has been awarded, among other honors Hero of Russia and Hero of the Soviet Union, ranks third for the amount of time spent in space: a total of 803 days, 9 hours, and 38 minutes.

Martinez asked Krikalev how mankind can leave politics aside and establish peace in space.

“It’s a challenging environment so in order to be efficient to work together we need to work in peace and in cooperation,” Krikalev said. “The Russian community is already working together for many years on the International Space Station project discussing ways how [we can fly] beyond Earth’s orbit. We should do this cooperatively because it’s the most efficient way to do it.”

Martinez asked, “And you have hope that we’ll get there?” To which Krikalev replied with a smile, “Well yeah, that’s why we’re working.”

This year’s Space Symposium comes on the heels of closed-door meetings between 25 spacefaring nations to determine just how militarized space will be. If successful, the meetings, which will end on March 28th, will result in a legally binding international treaty to define the rules guiding both space-based and anti-space weaponry.

The key point of contention in the talks is the U.S. displeasure at China and Russia’s development of anti-satellite capabilities, such as jammers and ground-to-space missiles.

“In the past, we have assumed that space is mostly a benign environment,” Brig. Gen. Tim Lawson, Deputy Commanding General for operations of U.S. Army Space and Missile Defense Command/Army Forces Strategic Command, said in the “Army Space Today” panel at last year’s symposium.

“That is no longer true. Future conflicts with a near-peer competitor will likely extend into the space domain. The first shots in a future conflict could be in space, done through jamming and spoofing, anti-satellite weapons and cyber attacks,” Lawson continued.

This year’s Space Symposium will feature discussions on the future of space as it pertains to sustainable space exploration, artificial intelligence and data, the impact of social media, the law of space, women, war and weaponry, and the commercial sector. The conference will also honor the legacy of high achieving figures in space whilst drawing on the global perspectives of diverse speakers who are undoubtedly shaping history on their quests into space. Among many other notable participants, Senior Army Aviator and astronaut LTC Anne C. McClain will be speaking at the Symposium. Dr. Kathryn C. Thornton, former astronaut and Vice Chairman of the Space Foundation Board of Directors, will also be at the conference.

Who are we? We find that we live on an insignificant planet of a humdrum star lost in a galaxy tucked away in some forgotten corner of a universe in which there are far more galaxies than people.

-Carl Sagan

Everyone’s in Space!

The first Pan-Arab Space Agency, the Arab Group for Space Collaboration, is now underway, as of just two weeks ago. An African Space Agency (AfriSpace), with Egypt as its host country (draft statute), has also been proposed, along with a South American Space Agency (SASA).

Numerous specialized organizations have also been created. The Inter-Agency Space Debris Coordination Committee (IADC), the Group on Earth Observation (GEO), the Committee on Earth Observation Satellites (CEOS), and the International Committee on Global Navigation Satellite Systems (ICG) are just some. Intersputnik is an organization in which 26 member nations, mostly former Eastern bloc (FSU) nations, collaborate in the development and common use of communications satellites.

Some governments or national space agencies enter into Framework Agreements for specific bilateral space projects, with Implementing Agreements (or Implementing Arrangements) to provide for specific mission details. An example is the International Space Station (ISS) Intergovernmental Agreement. The ISS cooperation is governed by a three-tier legal framework:

(a) the 1998 Intergovernmental Agreement on Space Station Cooperation (ISS/IGA) signed by the US, Russia, Canada, Japan, and participating Member States of ESA; (b) the 1998 Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) between NASA and ESA, Roscosmos and the Canadian Space Agency (CSA), as well as NASA and the government of Japan; and

(c) various “Implementing Arrangements” between NASA and another space agency, when the need arises.

Expected to operate until 2030, the first component of the ISS was launched into orbit in 1998, its first long-term residents arrived in November 2000, and it has been inhabited continuously since that date. As of March 14, 2019, 236 people from 18 countries had visited the space station, many of them multiple times.

Russia's Progress 72 cargo ship docked at 10:22am ET today to the station's Pirs docking compartment 254 miles over central China delivering 3.7 tons of supplies. #AskNASA | https://t.co/gZmSELZBdh pic.twitter.com/bcEYFt3wsp

— Intl. Space Station (@Space_Station) April 4, 2019

https://twitter.com/roscosmos/status/1113809495455600647

Organizations such as the Asia-Pacific Regional Space Agency Forum (APRSAF) also foster cooperation where space agencies, governmental bodies, international organizations, private companies, universities, and research institutes from over 40 countries and regions take part in an annual conference.

Even when I see countries pushing apart internationally and in other areas, in space we will continue to cooperate.

-Dr. Alice Bunn, International Director, UK Space Agency

The U.S. Space Symposium is also an example of a forum for cooperation (via the U.S. Space Foundation) that can bring together countries and leaders in the space industry.

At this year’s 35th annual Space Symposium, leaders of government space agencies from around the world will speak, such as Dr. Mohamed Nasser Al Ahbabi, the Director General of the UAE Space Agency, and Dr. Grzegorz Brona, President of the Polish Space Agency.

Dr. Erna Sri Adiningsih, Prime Secretary of Indonesia’s space agency, the Indonesian National Institute of Aeronautics and Space (or Lembaga Penerbangan Dan Antariksa Nasional)(LAPAN), will also speak, along with Dr. Thomas Djamaluddin, Chairman of LAPAN. Indonesia is one of about two dozen countries that have also codified a national space policy. (See list with links to laws and regulations submitted to UNOOSA and list with links by the European Centre for Space Law [ECSL]). The Indonesian Space Act (ISA, 2013), a 60 page document that begins with the pronouncement, “BY THE BLESSINGS OF ALMIGHTY GOD,” aims to achieve self-sufficiency and competitiveness for Indonesia in space activities. It also aims to capitalize on Indonesia’s geographic advantage (a vast equatorial territory situated between two continents and two oceans), “for the advancement of civilization and the prosperity of the people of Indonesia and for all human kind in general.” Indonesia’s space activities include meteorology, navigation, communication, exploration, remote sensing, commercial use, along with military applications that include command, control, computer intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance.

Along with Indonesia, SpaceWatch recently published a report about Southeast Asia’s emerging space programs, estimating that ASEAN’s space industry, as of 2018, is valued at U.S.$360 billion and is projected to grow at a CAGR of 5.6 percent, and reach a value of U.S.$558 billion by 2026. According to the report (citing Euroconsult), in 2012, Vietnam was the largest spender (U.S.$93 million), followed by Laos (U.S.$87 million), Indonesia (U.S.$38 million), Thailand (U.S.$20 million), and Malaysia (U.S.$18 million). Except for Singapore, the Philippines, Laos, Myanmar, Cambodia, and Brunei, all have yet to establish a dedicated space agency or space program, with most collaborating with other countries or companies for satellite access.

Notably, the report states that the ASEAN space programs overall “are motivated largely by socio-economic requirements and a desire to nurture self-reliance in the area of security. They are interested less in prestigious projects such as sending missions to outer space, and more in enhancing economic development using better technologies, as well as, for some of them, competing in commercial markets for providing space services.”

Representing Japan’s Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA), is astronaut Dr. Koichi Wakata, who, as of this writing, accumulated 347 days 8 hours 33 minutes in space spanning four missions, setting a record in Japanese human space flight history for the longest stay in space. Dr. Wakata also become the first Japanese ISS Commander, in 2014. Wakata will be joined by Dr. Hiroshi Yamakawa, President of JAXA, and Takayuki Imoto, Project Manager, Epsilon Rocket Project Team, JAXA.

This Friday, Japan’s space agency JAXA successfully dropped an explosive on an asteroid for the first time. JAXA’s Hayabusa2 spacecraft released a basketball-sized copper ball to form a crater in the asteroid, in order to make way for the collection of samples beneath the asteroid’s surface. The mission was particularly dangerous because the Hayabusa2 had to move quickly out of the way of the debris from the impact. The asteroid, “162173 Ryugu” (Dragon Palace) is named after an undersea palace in a Japanese folktale. Ryugu, which measures approximately 1 kilometer (0.6 mi) in diameter, orbits the sun every 16 months and is about 300 million kilometers (180 million miles) from Earth.

Dr. Sang-Ryool Lee, Vice President of Korea’s Aerospace Research Institute (KARI) will be speaking as well. In December 2016, KARI signed a lunar exploration technical cooperation agreement with NASA in connection with Korea’s Lunar Exploration Program. A lunar obiter known as “Pathfinder” will be equipped with five payloads developed in Korea, and one payload to be developed by NASA.

Vibrant space programs have also emerged out of the Middle East, North Africa (MENA).

Dr. Ahmad Belhoul Al Falasi, Chairman of the United Arab Emirates Space Agency (UAESA) will also be speaking at the Space Symposium. UAESA, which was established in 2014, entered into an agreement with Bahrain’s National Space Science Agency last year to train a “Bahrain Space Team” tasked with developing satellite technology, design, construction, testing, launching, operations, and control, and carrying out environmental studies.

In an interview with The National, Al Falasi stated that UAE space programs and initiatives include the UAE Astronaut Program, the Emirates Mars Mission’s Hope Probe project, and a project known as “Mars Scientific City”.

![Image [Graphic of the United Arab Emirates plan to make a human colony on the red planet by the 2117. (Bjarke Ingels)]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/UAE-Mars.png)

Sheikh Mohammed bin Rashid Al Maktoum, Vice President and Prime Minister of the UAE, and Ruler of Dubai announced, “Today … we attended the signing of a charter to establish the first Arab body for space cooperation, bringing together 11 Arab states. Its first project will be a satellite that Arab scientists will jointly develop in the UAE. This satellite will be called ‘813’, which is the year in which the House of Wisdom in Baghdad reached the height of its reputation during the reign of Al-Ma’mun. The House of Wisdom brought together scientists, translated books of knowledge and became a place where the region’s scientific community flourished.”

During the opening of the Global Space Congress in Abu Dhabi, we attended the launch of the first Arab space coordination group that includes 11 countries. The group’s first project will be a satellite built by Arab scientists in the UAE. I personally believe in Arab talents. pic.twitter.com/mANWNmUwar

— HH Sheikh Mohammed (@HHShkMohd) March 19, 2019

Sheikh Mohammed bin Rashid vowed in 2017 to send four Emirati astronauts to the ISS by 2022. Current members of the Arab Group for Space Collaboration include Algeria, Bahrain, Egypt, Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Morocco, Oman, Saudi Arabia, Sudan, and the United Arab Emirates.

Dr. Francisco Mendieta, from Mexico, is another speaker on the roster. He serves as the Director General of the Mexican Space Agency, which signed a collaboration agreement with the Hellenic Space Agency in early 2019. Christodoulos Protopapas, the President of the Hellenic Space Agency of Greece, will also be speaking at the Symposium. The two space agencies have agreed to exchange scientists, plan joint events and seminars, and collaborate at national and international space conferences.

Anthony Murfett, Deputy Head, will be speaking on behalf of the Australian Space Agency. The ASA launched a new brand in December 2018, one that “is a result of consultation with members of Australian Indigenous communities and Indigenous astronomy experts.” According to ASA, “Indigenous Australians are our first scientists and astronomers, and their knowledge and contributions to Australian science are reflected through the new Australian Space Agency brand.” As a result, the ASA brand consists of a night sky view, including “eight Aboriginal constellations and star maps.”

The Australian Space Agency is proud to launch our new brand, one that serves our nation, honours our past and builds the future.https://t.co/AgdXGOxNFH pic.twitter.com/OEggh6HIlU

— Australian Space Agency (@AusSpaceAgency) December 12, 2018

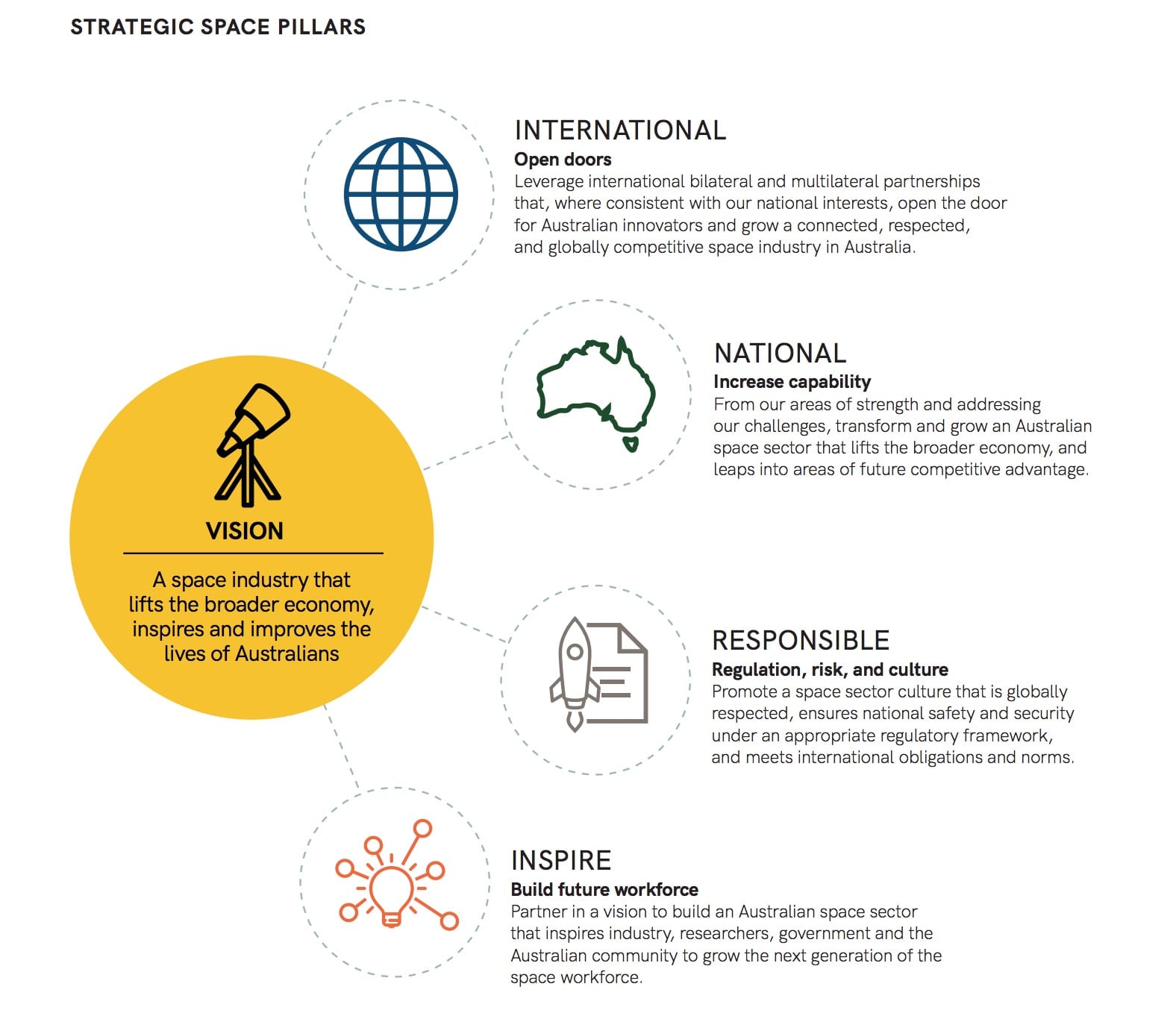

The Australian Civil Space Strategy just this April released its 2019-2028 outline of Australia’s plan to “transform and grow” its space industry over 10 years, identifying four Strategic Space Pillars.

From Italy, the Special Commissioner of the Italian Space Agency, Piero Benvenuti will be speaking as well as Donato Amoroso, CEO of Thales Alenia Space, an aerospace manufacturer that focuses on satellites. Thales Alenia Space has recently made news for incorporating 3D printing into the production of its satellites. On March 21, the Italian Space Agency launched a rocket carrying a new PRISMA Earth-observation satellite that is designed to collect information for environmental monitoring, management of natural resources, pollution and crop health.

Dr. David Parker, Director of Human and Robotic Exploration, for the European Space Agency (ESA), will be speaking, along with Dr. Johann-Dietrich Wörner, the Director General of the ESA, tasked with coordinating the manifold space programs across Europe. This means managing Europe’s relations with outside space agencies, most frequently NASA. In February, Wörner brought Israel’s Aeronautics Industry into partnership with Europe for future moon exploration and colonization.

The Portuguese just founded a space agency (FCT) in March, 2019, with Dr. Chiara Manfletti taking over as President. Portugal’s ambitions are laid out in the ‘Portugal Space 2030’ plan, and includes intentions to turn the Azores into an international “space port.”

The Centre National d’Études Spatiales (CNES), France’s space agency, is represented by Dr. Jean-Yves Le Gall, its President. CNES is partnering with yet another country, India, which is working with the French to mount their first manned space mission, and to develop space surveillance technology for maritime security.

The Netherlands, represented by Nico J. van Putten, Deputy Director, Netherlands Space Office (NSO), is the technical heart of the broader European Space agency. The European Space Research and Technology Centre, based in the Netherlands, is the principle R&D center for Europe’s space technology, and employs over 2,500 engineers.

Dr. Marc Serres, Chief Executive Officer for the Luxembourg Space Agency (LSA), will also be speaking. The LSA is currently negotiating with Russia on an agreement to cooperate in the mining of space minerals. The LSA already has space mining agreements with Japan, Portugal, and the UAE.

The United Kingdom is in the process of disentangling its space program, the UK Space Agency (UKSA), from the broader European space program, and will be represented at the Space Symposium by Dr. Graham Turnock, Chief Executive Officer, and Dr. Alice Bunn, International Director. UKSA was formed in 2010 to replace the British National Space Centre (BNSC). The UK is focused on competing in the design and production of low cost and reusable telecommunications satellites.

Dr. Bunn, Fellow of the Royal Aeronautical Society, is also vice chair of the Council of the European Space Agency, and sits on the Board of Directors at the Space Foundation. Dr. Bunn recently delivered a TEDx Talk, “How diplomacy in space can inspire cooperation on Earth,” citing how, for example, international collaboration of satellite navigation systems and communication technologies can aid in addressing global environment issues, such as climate change, environmental security, and emergency response systems worldwide. Dr. Bunn states that space operations are “loosely marshaled” mainly by UN procedures which “tend to be voluntary in nature … tend to take many, many years of international negotiation, and I’m afraid, because of that they are often quite out of pace with technological development.”

“[E]ven when I see countries pushing apart internationally and in other areas, in space we will continue to cooperate … I am extremely hopeful that we will continue to cooperate.”

Dr. Bunn cites the International Space Station (ISS) as a prime example, “a marvel of international cooperation.” 103 countries have been involved in that program. “We have been living and working side by side in space for 18 years.” Bunn notes that NASA’s head recently cited it as “the most powerful example of international cooperation in the history of mankind.” Dr. Bunn looks ahead to the next step, a space station that orbits the moon.

“Space really forces you to take a big perspective. It forces you to look beyond cultural and political barriers.”

Unfortunately, there are no scheduled speakers this year from ROSCOSMOS, India’s ISRO or China’s CNSA. At the Space Foundation’s 33rd Space Symposium 30 countries attended, including China and Russia. At the 34th Space Symposium, more than 9,000 people from more than 40 countries including a delegation from Russia.

In 2018, Sputnik News reported about the Space Symposium with the headline, “Cosmonautics Demonstrates How US, Russia Should Work Together – Roscosmos”. Another report stated, “The Space Symposium comes amid heightened tensions between Russia and the United States. ” It quoted Anton Zhiganov, Executive Director for Business Development and Commercialization at ROSCOSMOS, “the cooperation between countries is fruitful because there will never be a single leader in space.”

“Despite the deterioration of relations between Moscow and Washington, space cooperation continues to flourish. In September, Roscosmos and NASA reached an agreement to build a gateway to future deep space missions in lunar orbit. The gateway’s segment that Russia intends to build will serve as an exit for cosmonauts going on spacewalks.”

Despite China’s public push for peace in space, recent satellite imagery has revealed the existence of secret anti-satellite weapons bases in territories like Tibet and Xinjiang. China has also been harboring electromagnetic pulse weapons testing facilities. These secret facilities are just part of a larger picture of China’s CNSA placing special emphasis on military space programs, testing its first anti-satellite weapon in 2005, and even threatening the U.S. military with special “trump card” space weapons in 2014.

Pierre Delsaux, a Deputy Director General at the European Commission, told Lima Charlie News at last year’s Space Symposium:

“We are at the Space Symposium because we want to explain that Europe is very important in space. For instance, during the last hurricane season in the U.S., the U.S. used images coming from Copernicus (the EU imaging satellite) to rescue people in Florida. The U.S. State Department thanked the EU for its contribution to helping saving lives in the U.S.”

Cooperation among the world’s space agencies is critical to both science and security. It is also critical to safety and the environment.

Clear skies with a chance of satellite debris.-Dr. Ryan Stone, as played by Sondra Bullock, in the film Gravity

Space Junk and ASATs

Waves of debris from a shattered satellite, destroyed by a Russian ASAT (anti-satellite weapon), race past George Clooney and Sondra Bullock traveling at thousands of miles per hour, devastating the fictitious space shuttle Explorer and the International Space Station. “Houston, I have a bad feeling about this mission,” George Clooney’s character Matt Kowalski had prophesied.

Despite taking some significant liberties with reality, the 2013 blockbuster film Gravity struck a chord with civilians worldwide. Military, space and academic experts had voiced concern about space junk and ASAT threats for years.

Space debris, or space pollution, has been a critical issue for some time now, particularly for its potential damage to existing satellites and orbital space stations. NASA reported in 2013 that more than 500,000 pieces of “space junk” tracked traveling at speeds up to 17,500 mph orbit the Earth. This doesn’t include many millions of pieces of debris that are so small they can’t be tracked. A 2015 GAO report indicated that the Air Force Joint Space Operations Center provided 671,727 collision warnings during 2014. This comes out to more than one warning per day for every satellite in orbit.

According to NASA, even tiny paint flecks can damage a spacecraft when traveling at these velocities, which has in fact resulted in damage to space shuttle windows. NASA has its own Orbital Debris Program tasked with studying and attempting to control space debris.

Weeks ago, India’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi declared that India had successfully launched an ASAT (Mission Shakti), making India the fourth country capable of destroying an enemy satellite, after the U.S., Russia and China. Reportedly, the U.S. military is monitoring over 250 pieces of space debris resulting from the test, sparking similar concerns from China’s 2007 ASAT test which left a large debris cloud in orbit. G. Satheesh Reddy, the chief of India’s Defense Research and Development Organization told Reuters, “That’s why we did it at lower altitude, it will vanish in no time.”

At a U.S. House of Representatives hearing on NASA’s proposed budget on March 27, NASA Administrator Jim Bridenstine was asked about the problem of space debris by U.S. Rep. Steven Palazzo. “Is it getting worse? How are we going to address that?” Palazzo added, “do we have any type of law in place that prevents other countries from detonating or exploding or polluting our space?”

“Yes, space debris is getting worse not better,” Bridenstine replied. “It’s important to note that NASA is a part of what’s called the Inter-Agency Space Debris Coordination Committee [IADC] … they have assessed … that every 5 to 9 years we are going to have a collision in orbit similar to the Iridium-Cosmos collision that occurred back in 2009 … in other words every five to nine years we’re going to have a collision that results in thousands of pieces of orbital debris that is trackable, which means there’s thousands of more pieces that are not trackable at this point.”

Formed in 1993, in addition to NASA, the IADC consists of 13 member space agencies that include China’s CNSA, Russia’s ROSCOSMOS, Ukraine’s SSAU, and India’s ISRO. The Iridium-Cosmos collision occurred on February 10, 2009, when an inactive Russian communications satellite (designated Cosmos 2251) collided with an active commercial communications satellite operated by U.S.-based Iridium Satellite LLC. The collision produced almost 2,000 pieces of debris, measuring at least ten centimeters (4 inches) in diameter, along with many thousands more smaller pieces of debris.

Bridenstine warned, “[d]ebris ends up being there for a long time. If we wreck space, we’re not getting it back.” He added, “it’s also important to note that creating debris fields intentionally is wrong. That’s an important point. Because some people like to test anti-satellite capabilities intentionally and create orbital debris fields that we today are still dealing with, and those same countries come to us for space situational awareness because of the debris field that they themselves created.” Bridenstine added, “the entire world needs to step up and say ‘if you’re going to do this you’re going to pay a consequence’ and right now that consequence is not being paid.”

At this year’s Space Symposium, representing Poland’s space agency, Polska Agencja Kosmiczna (POLSA), is its President Grzegorz Brona, who is also co-founder of Creotech Instruments S.A., one of the largest Polish companies operating in the space sector. This February, Poland joined the Space Surveillance and Tracking (SST) Consortium, which was established by the European Commission in 2015 to track space debris. EUSST began with five EU Member States (France, Germany, Italy, Spain, UK), adding Poland, and soon Portugal and Romania’s ROSA space agency.

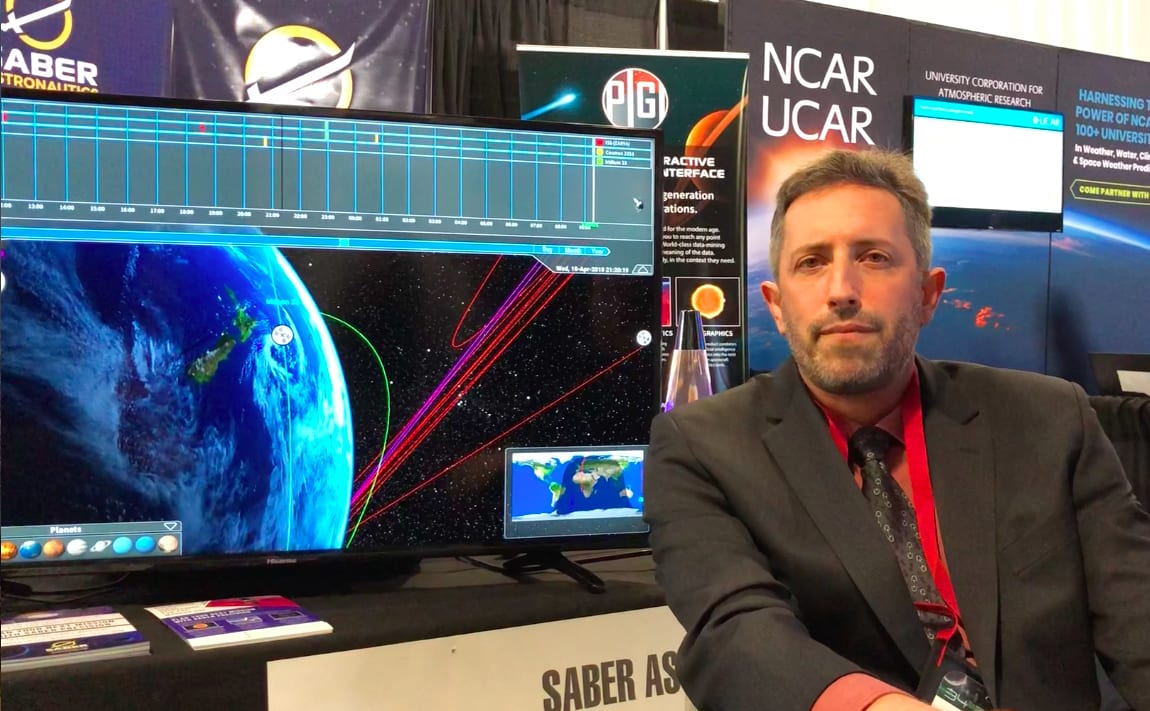

At last year’s Space Symposium, Lima Charlie News interviewed Jason Held, CEO of Saber Astronautics, who built a technology called DragEN (Deployable for Recovery through Atmospheric Gravity ENtry), an electrodynamic tether designed to drag satellites back to Earth, where they would combust upon re-entry.

Held warned, “We expect the number of small satellites to triple in the next ten years so management of space debris is critical. This is both a problem of controlling the debris itself as well as giving mission operators the tools to respond to debris fields in the first place.”

Held, a U.S. Army veteran and leader of an Army Space Support Team (ARSST) for USSTRATCOM (formerly Space Command), told Lima Charlie World this month that the DragEN is currently in use by university projects with a flight scheduled next year in Australia by CUAVA (the ARC Training Centre for CubeSats, Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs), and their Applications). CubeSats, a new class of small, low cost satellites that utilize UAVs (or nanosatellites), have “disrupted” the international satellite market. Over 1000 CubeSats have been launched as of January 2019.

Held said that previously DragEN was part of NASA Flight Opportunities, “which we used to validate rollout stability and deceleration of the device. Next step is to make it retractable and to research mechanisms to increase the lorenz force (which is the mechanism to deorbit).”

Held also developed “PIGI” (Predictive Interactive Groundstation Interface), a unique Mission Control software, “which uses some really good visuals so operators can manage large numbers of space objects with minimal training uptime.”

Saber Astronautics has also developed tools that will assist tracking (that ties into PIGI), “but that’s not released yet.”

Military Veterans & Space

Military veterans are often key figures in space programs worldwide. In the U.S. alone, 219 of the 330 current and former astronauts have previously served with the armed forces. The current Director General of the UAE’s Space Agency is also a veteran of the UAE Armed Forces.

At last year’s Space Symposium, Lima Charlie interviewed dozens of military veterans that had transitioned into space programs or the space industry. Don Martinez asked each for any advice on how best to enter the space field.

Lt. Col. Mark M. Moody served as engineer officer with the U.S. Army Reserve and National Guard. He is now a lead NASA engineer for testing rocket propulsion. He recommended internships available to veteran students saying that there is a “one-stop shopping initiative [called OSSI] which offers college students intern opportunities at NASA.”

Patrick Parnell served with the U.S. Army and Air Force as an Intel and Special Weapons officer, and he is now Vice President of Sales at Epoch Concepts. He noted that the “core values of mission and character and integrity” that veterans gain during their service is important to the space industry. “Stay plugged in tight with your military brethren,” he said, in order to transition those values stateside.

Jim Gillespie, a 32-year veteran of the Royal Canadian Air Force, mentioned that Canadian service members can actually register with a couple of agencies to get into the space field. “We actually have a preference for hiring veterans,” Gillespie said.

Duane Carey, an astronaut and retired lieutenant colonel in the U.S. Air Force commented that working in space enables people to see “the big picture” and take a different perspective on what militaries are fighting about in the first place.

Scott “Scooter” Altman, a retired U.S. Navy captain, told Lima Charlie that “space is a great way to establish peace relations and understanding” given his experience working with veterans from the armed forces of other nations.

Lima Charlie will have multiple reporters on the ground recording and reporting on the many conversations, panels, and exhibits at this year’s Space Symposium. Stay tuned to Lima Charlie World for the latest from the 35th Space Symposium.

Anthony A. LoPresti, LIMA CHARLIE NEWS

[Don Martinez and Diego Lynch contributed to this article]

[Subscribe to our newsletter for free and be the first to get Lima Charlie World updates delivered right to your inbox.]

Lima Charlie World provides global news, featuring insight & analysis by military veterans, intelligence professionals and foreign policy experts Worldwide.

For up-to-date news, please follow us on twitter at @LimaCharlieNews

In case you missed it:

![Image Imagine a Global Space Community ... The Space Foundation Can [Lima Charlie News][Graphic by Anthony A. LoPresti]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/Space-Foundation-Space-Symposium-Lima-Charlie-News.png)

![Image Vietnam to Iraq - America's Lessons Never Learned [Lima Charlie News] [Photo: Anja Niedringhaus / AP]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/Vietnam-to-Iraq-Americas-Lessons-Never-Learned-Lima-Charlie-News-480x384.jpg)