On April 4th the Syrian government, from its seat in Damascus, seemingly ordered a gas attack on the rebel-held, but predominantly civilian, town of Khan Sheikhoun in the Idlib province. This town was held largely by al Nusra, the overt Syrian arm of the global jihadist movement al Qaeda. The attack resulted in a reported 74 people dead, 11 of whom were children, and more than 150 people injured. Follow up airstrikes disabled the town’s central hospital. The Damascus government has acknowledged that the town was struck by a chemical agent, but states that it was not the Syrian government nor its Russian ally. Instead the government says that the chemical agent came from a chemical weapons factory in the outskirts of the town, and the government alleges that chemical agents were released into the air during an attack by the Syrian Arab Army – the official army of Syria. The factory was operated by the al Qaeda affiliated umbrella group known as Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS).

Experts on the matter of chemical warfare and the agents thereof have stated that the scenario that the Syrian government is painting appears unlikely, that the binary form of the agents most likely used – sarin or chlorine – would likely not be found in ready made form inside the factory, the agents have relatively short shelf lives once composed and combined into their ready form. Experts also state that if the compounds had been stored in their ready form, in the HTS chemical factory, they would likely not have been in the quantity that would be required for the scale of the attack.

The Syrian government has, however, refused to comment on the follow-up attacks that disabled the hospital, which was at the time treating the victims of the chemical attack, and caused large parts of the ceiling to come crashing down upon the first responders and the victims alike.

The thing is, however, details of the attack remain to be ironed out. Large parts of the events that unfolded remain firmly in the alleged category. If the attack is proven to have been carried out, as it has been alleged, by the Syrian government then it would be one of the deadliest attacks in Syria since the civil war began six years ago.

The Syrian government has a history of utilizing chemical weapons and denying having done so. In 2013 the Damascus-government is believed to have ordered, and carried out, at least 5 such attacks against opposition positions. The most famous ones were the attack on the Ghouta suburbs of Damascus, and the attack on the Khan al-Asal suburbs of Aleppo. The Syrian government did not claim responsibility for the attacks, but remains the main suspect. Investigations by both a special United Nations fact-finding mission and a UNHRC Commission of Inquiry found that sarin gas was used in the attacks on Khan al-Asal, Saraqib, and Ghouta attacks, while the Jobar and Ashrafiyat Sahnaya attacks are believed to have been carried out using chlorine gas. Other than identifying the type of agents used, the investigations resulted in very little except for leveling inconclusive accusations against Damascus.

The attacks prompted the Damascus government to agree to the destruction of its chemical weapons, which was deemed completed by the 23rd of June 2014. The destruction was carried out by the US Government, and totalled 600 metric tons of chemical agents. Despite this, several monitoring organizations, such as the Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons, have documented over a hundred instances where the Syrian armed forces appear to have used toxic chemical compounds and agents against opposition and civilians alike.

Rumors have circulated for a few years now that the Damascus government, along with its President-for-life Bashar al Assad, lost control over parts of its chemical warfare stock some years ago, that it fell into the hands of advancing militia groups. A handful of groups have been accused of holding parts, or all, of this missing stock. The Syrian government itself claims to have destroyed its ready-to-be-used stockpile. In other words, it is alleged that there is an unaccounted stock-pile of Syrian chemical agents that could be used by anyone. It could have been recaptured by the advancing Syrian Arab Army (SAA), and kept off the books. It could also have been destroyed in one of the many air strike carried out by the anti-ISIS coalition or the pro-Damascus regime coalition. Depending on the storage conditions, it could also have already expired. But it could also still be in the hands of a militia group.

If the Syrian government, along with its Russian ally, can prove that the attack was in actuality carried out by a militia group – it would solidify the international support for the al Assad-led Damascus government with ease. If, on the other hand, the attack was carried out by the government, it is questionable what would come of it.

Historically, Western response to Syrian affairs has been lukewarm, and al Assad grew up knowing that the West will only interfere when events in Syria threaten Western interests. The Obama administration’s “Red Line” was an example of this, where an administration that had a skewed and misaligned understanding of the region got a very public reality check. This was one of many such reality checks. Now the Trump administration appears to be building a new, overt, anti-Assad strategy on the bodies of the dead in the jihadist-held town of Khan Sheikhoun. But can the administration create a viable strategy where others have failed? Out of a historically viable perspective, as long as the Syrian government can keep denying any action that they might have taken, while blocking any international community investigations, the outrage tends to subside rather quickly. As long as al Assad can deal with the opposition before the American rose tinted lenses come off entirely, he might very well be proven victorious still.

There is however a third option, of what could have happened, and that is the “rogue General” option. The regional rumor mill has in the past been quivering with the notion of the Damascus government no longer being in absolute control of its Generals and what atrocities they carry out in order to achieve their overall objective – to remove any threat to the Syrian status quo. If this is the case, then al Assad would still to some extent have to claim this act. His only other choice would be to do the most unthinkable thing that a despot and absolute ruler can do – admit to having lost control.

If one were to put any stock in the regional rumor mill, this would not be the first time that the al Assad family took ownership, of a deplorable act carried out by rogue entities for its own benefit. Nor is it the first time that an uprising by non-secular militia groups have threatened the al Assad family’s claim to absolute reign over Syria.

Between 1976 and 1982 the Damascus-government, under the leadership of Bashar al Assad’s father – Hafez al Assad, fought a militant uprising that seems to mirror the uprising that began in 2011, and which spiraled into the civil war of today. Arabists and security analysts agree that the Islamist uprising of 1976 came in three stages. Throughout the period of 1976-1979, the opposition operated as an insurgency. They targeted, and assassinated, ranking Syrian military, political leaders, and civilians alike. Most of the victims came from the secretive Alawi sect – the same sect that the al Assad family belongs to – and a branch of Shia Islam. The opposition in Syria came largely from the Salafist-Sunni believing Muslim Brotherhood inside the country. They had the backing of Saudi Arabia, which considered the Alawi sect to be an abomination of Islam.

Overtly, the Muslim Brotherhood claimed to be fighting the despotic rule of the Alawites, who were represented in Syria by the al Assad family and the Damascus government. They seemingly intended to create an open society where all the Islamic sects could jointly coexist. However, they wanted this open society to operate under the gentle guidance of a totalitarian extremist Salafist rule in the shape of the Muslim Brotherhood. It was a proposition that the Shia, Christians, and especially the Alawites, of Syria came to see as a threat to their very existence.

In the summer of 1979 the Muslim Brotherhood had attacked the Aleppo Artillery School, killing nearly 80 teenagers. One of the teachers at the school, Captain Ibrahim Yusuf, had been converted to the Muslim Brotherhood cause, and announced the assembling of cadets in the dining-hall. When a large number of cadets had gathered, Yusuf let in 4 Muslim Brotherhood-affiliated fighters, who quickly opened fire with AK47s into the crowd. The attack proved to be the precursor that the Damascus government needed to initiate a wide scale offensive on Muslim Brotherhood posts, and to detain individuals who might have ties to the Brotherhood. Thousands were detained, and hundreds were killed. The Muslim Brotherhood in turn used the Aleppo school attack, and the government response, to initiate a scaled urban guerrilla warfare insurgency targeting the Damascus-government representations and infrastructure.

Aleppo, ever the melting pot of trade, religion, and soulful poetry, continued to play an important role in the insurgency, and its claim for legitimacy. The very foundation of the Muslim Brotherhood’s quest, and path, towards rule can be traced back to the demonstrations that were carried out in the early 70s throughout Aleppo. During the civil war, hundreds of academics, Ba’thists, Alawis, and government affiliated individuals were killed by the Islamic insurgency. Many Imams throughout Aleppo denounced these acts of terror – so the Brotherhood murdered one of the most prominently outspoken clerics. In early February 1980, they killed Imam Shaykh Muhammed al-Shami in the center of Sulaymaniya, his own mosque. They made sure that there would be an audience for the killing, wanting to make sure that there was no question as to why the cleric was murdered.

As the war raged on, the government conducted sweeping crackdowns, throughout Aleppo in particular. Tens of thousands of soldiers, supported by helicopters and tanks, were deployed to quell any disruption in Aleppo. During the crackdowns, hundreds of demonstrators, and Islamic insurgents were killed, and around 8,000 were arrested, by the armed forces.

By November of 1979, the country was embroiled in a nationwide low intensity conflict. Strikes, and protests paralyzed the infrastructure and the economy of the country, in addition to the insurgency styled strikes against military and government installations. An assassination attempt on Hafez al Assad prompted an estimated 1,152 Islamist inmates at the prison in Palmyra to be massacred by government forces. A few weeks later, the government made membership in the Muslim Brotherhood an offense punishable by death. Members were given a month to disown the organization.

By February 1982, suicide bombings, street-to-street fighting, and terror attacks against all levels of society had resulted in large numbers of civilian collateral. The al Assad-led government was growing tired, and angry, of the situation. It all came to a breaking point at 03:00 on February 3rd, when a small unit of SAA soldiers were searching the old city of Hama. They “stumbled upon” (as the Syrian Armed Forces statement claimed afterwards), the base of operations of the local guerilla commander, Omar Jawwad (also known as Abu Bakr). Abu Bakr ordered the unit to be ambushed, unaware that army reinforcements were minutes away. The troops quickly received reinforcements, and were able to fight the ambush back – so Abu Bakr announced, in the middle of the night, the call for a general uprising throughout the city. Mosque speakers ordinarily used for the call to prayer were now, at 03:45 in the morning, announcing the jihad against the Syrian government forces inside and outside of Hama. Hundreds of armed Islamist insurgents ventured out into the streets, and attacked government positions. The Muslim Brotherhood insurgency quickly overran the police stations, taking any arms that they could find, and executed leading government party affiliated members. By dawn, 70 Syrian government officials had been killed, and the Islamist insurgents had proclaimed Hama to be “liberated” from the infidel government.

The Muslim Brotherhood had sealed off the city of Hama, declaring it independent from the Syrian regime. Al Assad sent all available troops to lay siege to the city, and ordered his youngest brother – Syrian Arab Army General Rifaat al Assad, to enter the city, and take it back. For 27 days the siege, and battle, for Hama raged. At the end of February, an estimated 20,000 civilians were dead, along with 1,000 government soldiers. Robert Fisk, of The Independent, went to Hama shortly after the massacre. He originally estimated fatalities at 10,000, but doubled the estimate to 20,000 after seeing more of the city. Even that number is often considered to be low. Amnesty International initially estimated the death toll to be nearly 25,000, while the anti-regime group Syrian Human Rights Watch, estimates the number to be between 30,000 and 40,000. The Syrian Muslim Brotherhood stated, at the time, that the number was closer to 40,000.

The man in charge of the operation, the president’s brother Rifaat, in turn publicly boasted that the number of dead at the hands of his forces was 38,000.

I found plenty of silence to contemplate in Hama, because by the time I got there the waterwheels were broken. The muezzin’s voice was deathly still, and the only cries anyone heard permeating the narrow streets came from the widows and orphans who had survived the massacre. Even when I arrived, some two months after the mass killings, all the blood had not been washed away into the Orontes River.

-Thomas L. Friedman, “From Beirut to Jerusalem”, Chapter “Hama Rules”

Rumor has it that while the President wanted the city cleared, he did not want what came. The numbers came from the ferocity and “at any cost” mentality of his brother. However, the damage had been done. And with that in mind, the Syrian government denied that it had ever happened, letting the events become the stuff of legends, for just long enough that it suited them. In the end, the legend of what happened at Hama played no small role in keeping the Alawites, and the al Assad family, in power with little to any real opposition for over 30 years.

This is the way that President Hafez al Assad, the father of the current President of Syria – Bashar al Assad, ruled and dealt with opposition. Opposition, in whatever shape or form it takes, must be removed. This was even at the cost of truth, or the lives of thousands of civilians. And it is in this that we see quite clearly why the al Assad’s regime response to the original 2011 Arab Spring uprising, which had secular tendencies and could have morphed into something useful for all parties, was what it was.

Years later, General Rifaat would come to be one of the most vocal opponents of the succession of Bashar to the post of President of Syria. Rifaat believed that he, and he alone, embodied the “only constitutional legality”, and that he intends to come back to rule, benevolently and democratically, with “the power of the people and the army” behind him. He currently lives in exile, in France, and appears to be sitting the current turmoil out.

What is Raqqa to Idlib?

With the Western World’s case of attention deficit disorder regarding the Middle East and the events thereof, it remains a fact that the average news consumer will only be able to engage with one news item, or one linear set of events, at a time. This explains the complete current focus on the fight against the Islamic State. Western Media remains, on the whole, a profit driven advertising affair and as such, the focus will always remain on singular topics while ignoring the complex mosaic of the nuanced reality on the ground. This has made certain clusters of leisure news consumers unaware that the war in Syria did not begin by or because of the emergence of the Islamic State and its terror.

The Islamic State is but an ambitious terrorist organization that rebelled against its parent organization, al Qaeda in the Levant, and filled a vacuum. The vacuum was there, largely, because of the Syrian civil war.

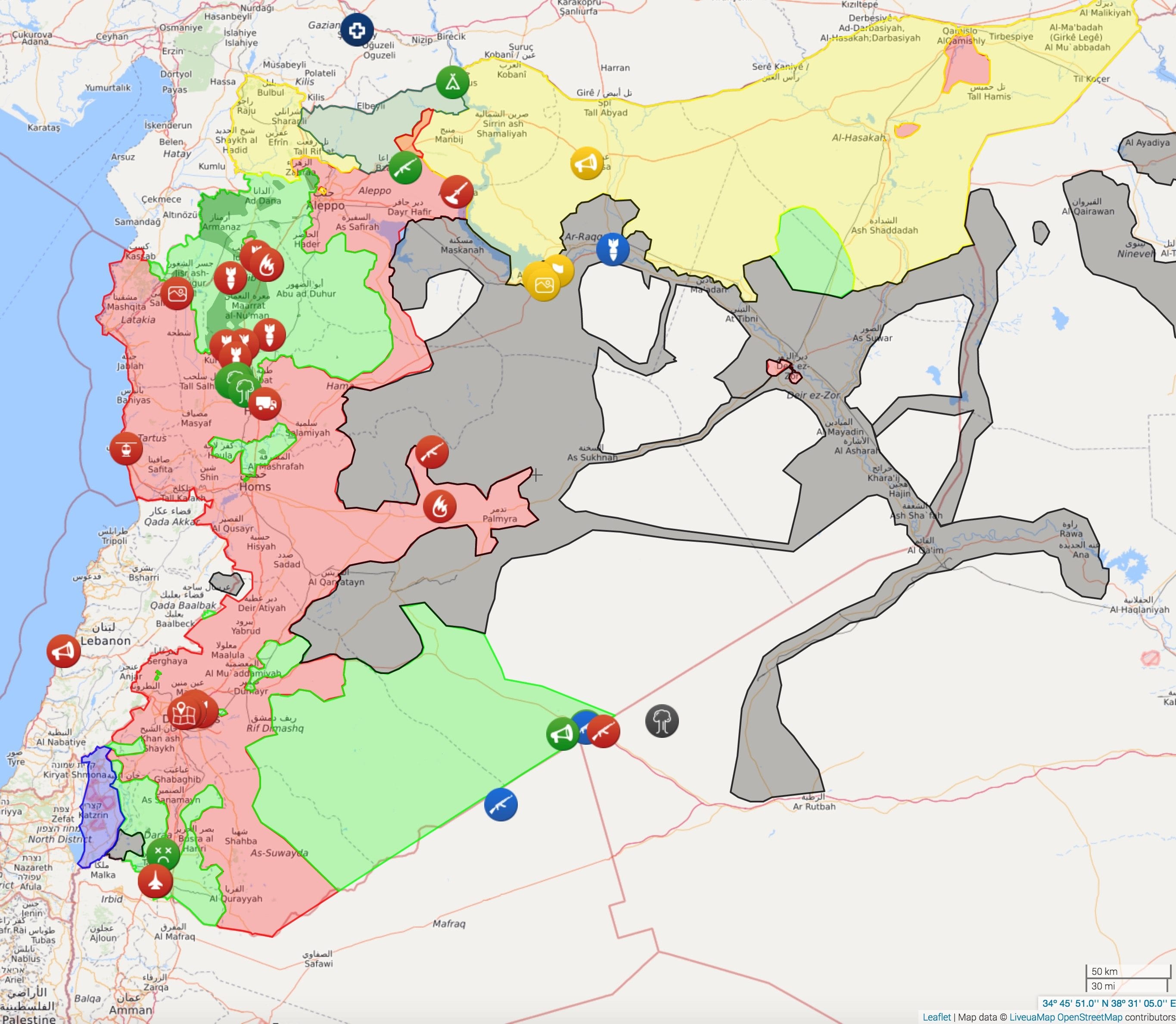

As such, the Islamic State self-declared capital of its caliphate, al Raqqa, is not where the future of the civil war, or the civil rights movement, will be decided. No, that litmus test is decided, as it stands now, in Idlib, Homs, and Hama. History is circular, with its cycles seeming more frequent, and as such we should pay careful attention to what happens on these fronts.

The history of Aleppo has already been written. It is the same as it was the last time – at the end of the last Syrian civil war. The situation began as a grassroots expression of a discontented society, discontented with the authoritarian rule of President al Assad. The winds of change swept through the region as the Arab Spring movement inspired a despondent people. It was as part of the tail wind of this that the problems began. If the al Assad-led Damascus government had responded suitably with an interest of introducing change, even if only for the sake of perception, things could have gone very differently. Instead the government responded as it had historically, with violence. This ensured that the protests became an uprising, quickly escalating matters to an armed conflict.

The escalation also caused more extreme fringe elements, the Islamic insurgents and jihadist movements, to take hold – pushing out the more moderate elements. As a result of this, the Islamic State emerged. With it, came a unified enemy that suited the need for constant news cycles, for the coverage of al Qaeda had become stagnated. The Western audience always needs something new with which to entertain itself, and feel outrage over. Now, the focus is entirely on the Islamic State and the threat that it represents.

As the strategic threat from the Islamic State diminishes, the dynamics in Syria, Iraq – the Levant at large, are shifting quickly. The Damascus-government is seeing its country being divided by new interests that might have lasting consequences on how it can govern within its existing borders.

The Kurds have gained a great deal of renewed support from both Washington and Moscow in recent days. With the Kurds now controlling vitally strategic assets, such as the Tabqa Air Base, a time might even come when they can compete with Turkish interests when it comes time to consider the magnitude of Western troops stationed at the Incirlik Air Base. In recent months the Kurdish Regional Government (KRG) and militia factions, such as the Syrian Kurdish People’s Protection Units (YPG), have reached agreements to cooperate with both Moscow, and Washington. With these developments, the Syrian government is seeing itself lose control of the Syrian future and its message. This in turn means that it is now seeking to double down and secure what territory, and influence it can without having to withstand a possible future showdown with its de facto American allies, or its long standing Russian allies, in the battle against the Islamic State.

It is in this light that the ramping up of military operations in the Hama and Idlib provinces is coming. These are areas where the Syrian military can put its might up against the opposition without too much interference from its allies, for this is where Salafist militia groups are the most active. Such groups as the al Qaeda affiliated umbrella organization Hayat Tahrir al Sham (HST), or, among others, various Turkish backed militia groups, have taken hold in this area – often after having lost their foothold to the Islamic State on other fronts, or to the advancing Syrian Arab Army forces. As such, the regime has found a battleground where it can be as aggressive as it needs to be.

As the Hama frontline has largely become dominated by Salafist militia groups, the Idlib front remains one of the few fronts where even remotely moderate militia groups remain as viable fighting entities. As such, it is a frontline that the Syrian regime perceives it must seek to devastate before the Western world wakes up out of its “fight the Islamic State at any cost” mentality.

Idlib has been in the focus of the Syrian government and opposition alike since the early days of the 2011 Arab Spring movement. The city, and province, of Idlib saw some of the first initial larger protests, and was one of the first places that the opposition laid claim upon when it began its military campaign. It was not until April 2012 that the Syrian government was able to mount a counteroffensive with the goal to retake Idlib. A few months later that same year, the government forces had succeeded in reclaiming the majority of the province, including the majority of the namesake city. As the conflict spiraled out of control, with civilians being caught in the middle and collateral casualty numbers skyrocketing, the Secretary-General of the United Nations at the time, Mr. Kofi Annan, made a personal matter out of seeking a ceasefire agreement between the warring parties. The ceasefire agreement that was reached was predictably only adhered to for as long as it took them to resupply their frontline units.

By 2015, the reshaped opposition launched another offensive on the Idlib province. The opposition had changed significantly. It had morphed into a significantly wider array of secular and non-secular militia groups. The new campaign that was mounted saw the besieging of the Shi’a towns of al-Fu’ah and Kafirya to the north of Idlib City. In April 2015, the opposition was able to create an interim government in Idlib City. The primary reason that the opposition forces were able to regain control over the Idlib province was largely due to the Syrian armed forces being engaged on multiple other fronts. The battle over Aleppo was in full swing, and most of the battle hardened veterans that the Syrian armed forces could muster were engaged in either Aleppo, or in defending the outskirts of Damascus from opposition forces. The Idlib interim opposition government has since then been forced into exile, to Turkey, in light of Syrian armed forces renewed efforts in the province.

And thus … The reality appears to be that the Syrian regime only knows one answer to civil disruptions, and that is to seek the total destruction of those that seek to undermine the power of al Assad family. The current Syrian president, Bashar al Assad, took a page out of his father’s playbook when he weighed his options, and chose his response to the 2011 Syrian reform movement. This strategy of complete annihilation of opposition worked for Bashar al Assad’s father, and seemingly Bashar believed that a similar strategy could still work in today’s world.

It still could.

The April 7th cruise missile attack carried out by the US can easily be perceived as a proportional response to the situation, assuming it does not escalate from this point. The dogmatic language that is being used to preemptively justify additional actions however, is likely to be nothing more than posturing and a very expensive battle rattle by an inexperienced President, who is not known for having a level head on his shoulders. This is a President who is attempting to appease his voting base, which largely consists of action-craving and emotionally charged Midwestern Americans that want a man with “balls” at the helm, all at the cost of about a hundred million dollars.

The 59 RGM/UGM-109E Tomahawk Land Attack Missiles, which were launched by the two US Navy warships anchored in the Mediterranean, targeted the airbase that the Pentagon believes the chemical attack to have originated, the Syrian Air Force Shayrat airbase. The cruise missiles struck a little before 04:00 local time. The US has said that no lives were lost and that only Syrian aircraft were destroyed in its attack. However, the Syrian media claims that 7 were killed, including 4 children. 58 of the 59 cruise missiles struck their designated target. The 59th missile struck some 50 meters from its intended target. The total cost for the missiles alone? A steal, just short of $94 million dollars.

This initial attack does not preclude the possibility of a more robust strategy, but does not create one.

The odds are that any strategy that the US Department of Defense has devised to dethrone President al Assad will focus on the military aspect, rather than the much more important, and complicated, nation-building aspect of the affair. It would certainly not surprise this observer to learn that any real plans to deal with the Damascus-regime will not have any more a notion of nation-building or stabilizing effort than those previously seen during the Iraqi incursion. No doubt, such problems will then be pushed aside, to be dealt with at a later point. At the present, the details of the attack remain somewhat obscure as well – and action of the kind that Trump is likely to seek would ensure that evidence of the attack is certainly lost in the abyss of violence and destruction.

Move fast and break things. Unless you are breaking stuff, you are not moving fast enough.

– Mark Zuckerberg

The fact is, as the problems in the region stand today, the US is much better served by having President al Assad at the helm in Damascus, to stabilize and steer a ship that has taken on a severe amount of damage and water. The Damascus government, and its armed forces, have proven quite valuable in the fight against the Islamic State – and regionally, Syria has had an appeasing influence on its neighbors. While looking at the situation out of a regional perspective, if the Alawite rule were to be diminished then it is likely that a Salafist Sunni rule would emerge. This would disrupt the Iran and Shia controlled corridor to Lebanon, something that in turn could be destabilizing in the short to medium term. Unless the US is invested in conducting a short sighted offensive to blindly remove al Assad from the Syrian helm, an act of immense cost and fraught with danger, then the acts seen on April 7th will result in little but additional expense to the American national defense budget.

And here we are … In other news, as with any other day in Syria, Syrian and Russian warplanes continue to carry out tens of airstrikes every day against various opposition positions throughout the country.

John Sjoholm, Middle East Bureau Chief, Lima Charlie News

[Edited by May Hamza][article submitted April 7, 2017]

John Sjoholm is Lima Charlie’s Middle East Bureau Chief, Managing Editor, and founder of the consulting firm Erudite Group. A seasoned expert on Middle East and North Africa matters, he has a background in security contracting and has served as a geopolitical advisor to regional leaders. He was educated in religion and languages in Sana’a, Yemen, and Cairo, Egypt, and has lived in the region since 2005, contributing to numerous Western-supported stabilisation projects. He currently resides in Jordan. Follow John on Twitter @JohnSjoholmLC

Lima Charlie World provides global news, featuring insight & analysis by military veterans, intelligence professionals and foreign policy experts Worldwide.

For up-to-date news, please follow us on twitter at @LimaCharlieNews

![Syria’s oil, gas and water - the Immiscible Solution to the War in Syria [Lima Charlie News][Photo: ANDREE KAISER / MCT]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/Syria’s-oil-gas-and-water-480x384.png)