Let it be known that all men are much like one another, but the best of men are trained in the severest of schools

– Thucydides

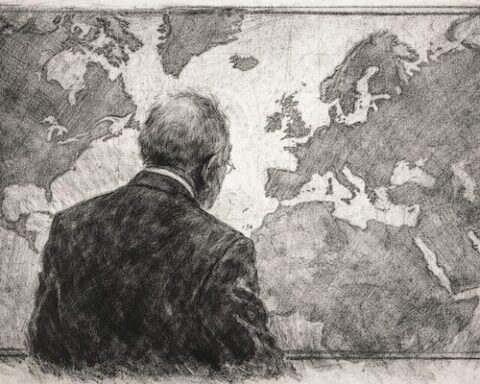

A U.S. Army combat veteran examines the noble profession of arms and the danger if the divide between Soldier and civilian becomes too great.

By Maj. Joe Labarbera, Lima Charlie News OpEd

Throughout man’s existence, there was in every gathering a small brand of men who stepped forth and offered their energy, talent, blood, their very future, to be on the altar of sacrifice for the safety and prosperity of their people. This was the warrior class. These were men who possessed a unique set of talents apart from others, yet they bore a restlessness that inhibited them from excelling at more common pursuits. Often seen as elite, they could thrive in an atmosphere of terror and chaos. It’s a quality some say is in their genes.

Such men are often called from early childhood, destined for the profession of arms. The calling to be a warrior matures into the profession of Soldiering. The difference being that a Soldier trades in the rashness of fighting, for the deliberation of victory.

The Soldier is often the cornerstone of a nation. Not profitable, not even useful, yet without his tangible protection of sovereignty and intangible representation of the best virtues of his nation, a society would fall apart. The Soldier caste has been, throughout the history of human existence, the fabric of a society’s ability to persevere.

The cultural dynamics of a society cut the mold for a Soldier’s excellence, and the irony is that when the Soldier reaches perfection, his profession then cuts the mold for society’s excellence. This irony can be both a blessing and a curse for a nation. The size of the space between the Soldier and the civilian allows the Soldier to excel. However, if the space is too great, the Soldier becomes his own caste, forming a nation within the nation. His profession’s values take precedence over his national ones.

This is why it is imperative that America today examine the American Soldier, and take stock of the growing space between America’s national character, and its Soldiers’ character. America must rethink the political and social influences pressed upon the profession of arms, and by doing so, check the direction of American progress.

To do this, the ideal Soldier should first be described. By examining history, the profession of arms, and the American national character, it is hoped that one can truly pay homage to the Soldier as the noblest professional mankind has ever known, and explain the American Soldier to the American people, so that understanding of such character may not be lost.

The ultimate Soldier is a mirror reflection of the best and worst of a nation

Achilles, Hector, Alexander, Hannibal, Julius Caesar, Belisarius, Attila, Flavius Aetius.

These epic great Soldiers of antiquity – legendary and historical – epitomize their times and professions, representing not just the profession of Arms, but their societies. They were very different men, who were very much alike. Achilles fought for vanity, Hector for his country, Alexander for glory, Hannibal for hatred, Julius Caesar for power, Belisarius for loyalty, Attila for revenge, and Flavius, for an ideal. All of these men were irreplaceable to their nations, and yet despised for their having been so valuable and necessary. Their lives and deeds were evidence that the ultimate Soldier is a mirror reflection of the best and worst of a nation, because that is precisely what war is – a torrent of events that overload the senses, where the best and worst of men are revealed.

These ancient Soldiers were a reflection of their people and their culture. They matured within the context of their world’s expectations. In studying their lives, their victories, their defeats, it is obvious their power came from an enormous capacity to channel the raw essence, the very passion of their people. This is why so many men followed them to the death. Why so many men of means resourced them, and put their names on the line for them. Ultimately, this is why thousands of years later, we know their names.

These Soldiers were the example, the ideal for what always was, still is, and will always be, the ultimate profession of manhood and patriotism, the only profession that trades in death and requires blood sacrifice. In the modern world we may, as Americans, scoff at these ancients as obsolete. But their truths are timeless, and through them we find our military virtue.

America was born in warfare, led by incredible Soldiers. These Soldiers set a precedent for what became the cultural standard for our military profession. Captain John Parker, who stood with his militia at Lexington, then Bunker Hill, with hunting rifles, facing and then locking horns with the mightiest Army in existence. Francis Marion, an expert guerilla fighter, whose tactics and daring kept a massive occupational field force pinned down. Benedict Arnold, the unquestionably most competent and courageous field commander of the war, yet a man whose vanity and flawed character led him to treason. Then Washington himself, the epitome of charisma, character, his daily habits an expression of virtue that established him as the great patriarch whose utter awesomeness has yet to be replicated.

Their deeds would become the examples for future American Soldiers. The military academy at West Point, established by Washington, became the bastion for military leadership that set the tone for American leadership to this day.

All of these men were civilians who easily transcended into a military role. The citizen was the Soldier, the space between citizen and Soldier was unnoticeable, much like the Roman Republic. Such was the early American Republic, hence why these societies were fiercely free, and culturally cohesive with respect to today’s society.

What makes Soldiering different from other professions is … the unknowingness, the void of ever being sure the sacrifice and effort was worthwhile, and not in vain.

Writing as a professional Soldier, I can’t help but be humbled by reading accounts of these men. It’s impossible for me to contemplate the virtues of the profession of arms without the backdrop of these heroes whose courage and character honestly far surpass my own. Even their failings invite my empathy, since I understand the last full measure of devotion that was their ceaseless existence. I understand the drive and the dedication that the profession of arms is to those who are committed to it. Any profession ultimately is a lifestyle, a way of life.

What makes Soldiering different from other professions is not just the level of sacrifice, or the demands that war’s violence places on one’s very soul. It’s the unknowingness, the void of ever being sure that the sacrifice and the effort was worthwhile, and not in vain.

A doctor saves a life, the good is beyond question. A lawyer exonerates the innocent, the good is beyond question. A Soldier wins a battle, and it doesn’t feel like winning. The Soldier doesn’t even know if it was a real victory. Will its cost lead to a future string of failures? The Soldiers’ very cause is often in doubt.

But the virtues of those who are called to the profession of arms, must stand as an example to a nation and its citizens.

The true Soldier is humble. He has been triumphant a few times, but broken many more times. His grasp of success and failure transcends the more mundane understanding of an athletic event, because unlike a game, failure to a Soldier is far more permanent, and winning to a Soldier is far less rewarding.

The true Soldier is a gentleman. He doesn’t waste harsh words, opinions, judgments or passions. Instead, he speaks and acts to constrain himself from provocation, and to maintain himself on his own terms. Just as he survived by not losing the initiative to the enemy, he lives in society aware that his worst enemy is himself.

The true Soldier is about truth. But he doesn’t proclaim it. He sees it as worthy of those only who suffer to learn it. The truths a Soldier knows are deep and intimate. So deep and profound that he may not have the words to articulate them, but will resent the more shallow truths of those who don’t share his experience.

The true Soldier knows that evil is real. He knows that it can happen to anyone, anywhere. The illogical becomes the essence of reality. He has lived with raw human drama, witnessing injustice, darkness, and utter misery. He stands up against it.

War. What is it Good For?

The cauldron of war makes or breaks the Soldier. It is war that allows the Soldier to truly know himself, making him aware of his fitness for the profession. When faced with the reality of war, some Soldiers embrace it. Others deny it, and further retreat into their institutional values, and try to conform war to their peacetime mores. Some collapse under the strain, never should having been Soldiers to begin with.

Amidst hunger, fatigue and frustration, a Soldier’s life in war is a journey into an abyss. The glories of valor are suffocated by the many shames of combat. At the war’s conclusion, the civilian is at peace, but the war lives on forever in the Soldier’s mind and soul. Strength, presence and tenacity all harbor a massive vulnerability that is expressed at the uncertainty of all that he is.

The Soldier, once he has run the spectrum of warfare, often becomes a very humble man. Little impresses him anymore. He becomes incapable of awe. He has seen the strongest break, the weakest rise to the occasion.

The Soldier learns the value of bearing, of self-imposed discipline and realizes the most powerful truth, which is that virtue can only be summoned from within and that it comes from a higher power. The true practice of virtue is often opportune to the Soldier, whose work is in an environment devoid of rules and order, and in that environment he is free to sin and blaspheme with no account to anyone save himself, God and his comrades. This is the test a Soldier experiences in war.

A Soldier who never experiences war lives in preparation for it, and exists to maintain the framework of the profession should war occur. This is either an orderly world of hard training and camaraderie, or a desperate one of schism and effete malaise. Either is dependent on the nation’s investment in the profession of arms during peacetime.

The difference between the peacetime and the wartime Soldier is the measuring stick in which they gaze upon the world. The wartime Soldier’s is broad, deep and vast, tolerant yet unforgiving and stand alone, fitting into any time and place. The peacetime Soldier’s is narrow, and acute, and unrelenting, yet acceptant of error as long as it is institutionally sanctioned, and ultimately relevant to his current era and modern mores. The Soldier who goes to war, but without his nation is often perplexed, as he will struggle to fit in to his home for the rest of his life. The peacetime Soldier will become narrowed to the confines of his institution, and often choose to separate himself from the society he serves.

The Soldier is often on the edge of losing his soul. For this to be at all bearable, he has to not just be the reflection for his nation to gaze into, but to see himself in his nation’s reflection. The Soldier must see his sacrifice as a seed for his nation to grow from, and find peace among his own people.

Woe unto the state that becomes disenfranchised with its Soldiers.

When a proud nation-state is a nation of Citizen-Soldiers, ideals run concurrently with the virtues of arms, and people celebrate their Soldiers, as did the early Roman and American republics. But when a nation turns course towards an empire, the Soldier becomes a necessary evil, a financial burden as the Empire’s values become maintaining a system instead of liberating it. Under an empire, the Soldier inevitably fights for his own displacement, as the citizenry sees them as foreign, alien, fearing and distrusting them, rewarding the Soldiers’ victories with ignominy.

The Soldier is at his apex when he comes to grip with the balance – or lack of balance – that hinges between his nation’s mores and his own virtues. This is his choice that he has to make, and to not come to grips with it condemns him to a life in limbo where he will painfully struggle to prosper, love, and find peace. If his inability to do so is inadvertent, which it often is, then his saving grace will be the pride and support of the profession, his comrades, sense of achievement that he can only feel upon reflecting his sacrifice against the backdrop of the nation he fought for.

If the nation’s mores become alien to the Soldier and vice versa, and the Soldier has withstood his trials intact, the Soldier may consciously choose to reject balancing his existence with his nation. Therein lies an indication that the Nation is no longer in keeping with its social contract, not just to the Soldier, but to the ideals it is predicated on.

The wise and strong Soldier becomes a fine man and citizen regardless of his views toward the imbalance between his profession and his nation. He conceals his resentment, and is careful about expressing his disapproval because he is disciplined, and understands the futility of wasted effort.

He does however, hold back. His talents and energies will not be freely offered to a nation that he no longer trusts or understands, but won’t be able to contest out of long ingrained loyalty. The Soldier will often lose faith and disassociate from the profession as it degrades to a mere institution.

This is the danger of a nation whose space between its citizenry and Soldier becomes too vast. The danger that the Soldier becomes too self-sustaining, too independent, standing for his own sake. The Soldier of a disenfranchised nation turns from being a Hector or a Flavius Aetius, into an Achilles, and ultimately into a Hannibal, or Julius Caesar. When this happens, the nation becomes the servant of the Soldier instead of vice versa.

A disenfranchised nation can fail to grasp that every day the Soldier struggles to find a balance to life. This is his curse for gazing into hell and seeing true darkness. To an America that is meandering farther and farther away from the profession of arms, the reality understood by the wartime Soldier will be at best a mystery to its citizens, and the American political class will shape the institutions of Soldiering to reflect itself, not understanding the dynamics of war. America’s future profession of arms will at best be blessed with a Belisarius, since it no longer has the context to produce a Washington, the space between itself and its Soldiers having become a void.

Joseph Labarbera, Lima Charlie News

Joseph Labarbera (USMC, U.S. Army) served as Command Inspector General at Ft. Irwin, California. Joe served 54 months combined OEF/OIF, with 46 months of combat in the Army’s 10th Mountain Division throughout Afghanistan and Iraq.

Lima Charlie provides global news, insight & analysis by military veterans and service members Worldwide.

For up-to-date news, please follow us on twitter at @LimaCharlieNews

![Image For the Sons of Mars: Meditations on the American Soldier [Lima Charlie News]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/Mars.jpg)

](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/Remembering-Becket-A-mothers-search-for-answers-480x384.png)

![Image Strike a deal with which devil? The many faces of the Taliban [Lima Charlie News][Image: Anthony A. LoPresti]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/Many-faces-of-the-Taliban-Lima-Charlie-News-Anthony-LoPresti-480x384.png)

](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/Remembering-Becket-A-mothers-search-for-answers-150x100.png)