| Abstract: The following Op-Ed follows the recent release of the Final Congressional Report on the 2012 terrorist attack in Benghazi, Libya. Written from the perspective of an active duty former US Army Infantry Officer and current Command Inspector General at Fort Irwin, this work embarks on a two-fold mission: 1) to explain the traits of post-Cold-War American power and leadership through the lens of the Benghazi attack, and 2) to urge a path of redirection upon which the next generation of American leadership can restore the Grand Republic and guide America back on track to being the world’s bastion of freedom. This piece is divided into the following sub-sections: (i) introduction to the Benghazi defeat as a microcosm of a greater issue facing the nation; (ii) brief examination of American political interest in the Arab World; (iii) survey of America’s past culture of great leadership; (iv) examination of the particular nature of the Benghazi diplomatic post and the State Department’s interest in this arena; (v) legal status of the Benghazi post and its capacity for protection under international law; and (vi) exploration of the Final Congressional Report and an in-depth analysis of how the military factored into the attack.

It was our fault, and our very great fault—and now we must turn it to use.

We have forty million reasons for failure, but not a single excuse.

– Kipling, The Lesson

We the American people have read and heard the play-by-plays of the Benghazi attack like an NFL football game. Now let’s get to the real story, by grasping the context so that the truth isn’t marginalized by myopia and disinformation.

The American diplomatic mission at Benghazi was defeated by a populist Islamic militia that resented the very American intrusion which, ironically, destroyed the regime that had been oppressing them. At the tactical level, a significantly large force of Jihadists were beaten off by the heroic efforts of a small team of former Servicemen who, armed with an Infantry Squad’s worth of weapons, defeated a battalion size assault. This was truly one of the finest and most incredible examples of fighting prowess in American history. Yet, the American government’s reaction was, without looking back, to retreat from the mission in a maneuver that imitated the American withdrawal from Somalia in 1993, an event that inspired Osama Bin Laden, calling America a “paper tiger” whose forces “run at the sight of blood.” The result has been paralyzing political schism, a loss of American prestige, and a decisive defeat to America in the eyes of the Salafist sect of Islam, which wages a continuing war on America and the West.

America’s strategic defeat at Benghazi is a microcosm of a greater issue facing America today. Articulating this issue is lengthy and complex but, in short, since the fall of the Soviet Union, America and its institutions have lacked leaders who are worthy of their office. There is a whole cult of these leaders who are now exclusive to the halls of power, products of a post-Cold-war dynamic. The Benghazi debacle is indicative of what happens when a government becomes out of touch with reality, and its subordinate institutions become disaffected with the aloofness of the Washington political apparatus. Historically akin to the complex and aloof Byzantine hierarchy of the latter Roman Empire, yet without a Belisarius to save the day.

America’s defeat at Benghazi was a heroic tactical victory where a handful of American warriors defeated a vast force against overwhelming odds. And, yet, strategically, an epic disaster that is arguably more harmful to American prestige than the losses at Saigon or Tehran. Benghazi shows us the many bad traits that have become symptomatic of American power. This work will explain them with the hope of redirecting America to a better future.

The higher level of grand strategy [is] that of conducting war with a far-sighted regard to the state of the peace that will follow.

– Sir Basil H. Liddell Hart

From 2010—2012, America’s diplomats used CIA subterfuge, employing the most deceptive tricks of their trade in a scheme to accomplish Neo-Con ambitions in the Arab world. Only this time, smarting from lessons learned in Iraq and Afghanistan, they excluded the military and all its might, and on their own, spawned a regional uprising and violent overthrow of the post-colonial governments. Great faith was placed in the paradigm that the young, pseudo-educated, social media savvy youth of that region would take over and create Western style democracies.

The current state of the Middle East is clear evidence of the senselessness of this project. “I assume this, therefore I am” should have been the leadership motto for the great Middle Eastern snafu, hailed in the media as the “Arab Spring.” In retrospect, the genesis of the Iraq War had much in common with the “Arab Spring” in that both were predicated on the fundamentally flawed assumption that mysterious groups of unknown people would “rise up” and establish an overnight republic, where law and order, perfect human rights, and economic prosperity would prevail. In both of these misadventures, the American government not only ignored, but ruthlessly stifled any planning or analysis which painted an accurate picture of the Arab world, a picture that challenges the paradigms of western liberality.

For both Neo-Cons and like-minded liberal allies, a puritanical missionary heritage compels them to force change in the region, which is seen as a modern day “white man’s burden” in need of Western re-engineering of its former colonies. This methodology, if it can even be called that has left little doubt in any political faction that the last 16 years of American government have been largely infective, if not counter-productive on the world stage.

The Benghazi tragedy—its report—shows a perfect storm of flaws, and also unfettered and unrewarded heroism. It has become highly emotional and politically charged, and should be seen in a calculating light as a microcosm of the greatest shortcoming since the end of the Cold War. Presented against the backdrop of “how things should be” we can examine the debacle at Benghazi to review our government’s actions in this time of crisis, and by doing this, determine where we need to change.

It’s all my fault, it’s all my fault!

– Gen. Robert E. Lee

To understand the significance of the Benghazi report, one must be in tune with the age-old virtues of leadership, and the unique American approach to them. Leadership can have many snappy definitions and many academic institutions attempt to teach it. The truth is, Leadership is an intangible characteristic that can’t be fully understood, or defined in its form, but absolutely understood in its effect. A leader, first and foremost, gets results, but also demonstrates the characteristics that inspire the more serious, the more decisive and the more resilient, to invest in, follow, kill and die, for the vision that this leader professes. A leader is an extreme person, and possesses the will to triumph, and most of all, places their nation, their cause, their following, above their own interests. This selfless aspect is the ultimate tell of a leader. A leader who serves his self interest at the expense of his following is in fact a tyrant. Many tyrants capitalize on established institutions and selfless patriots to mislead them into supporting ill-conceived efforts.

A Leader may also lead in err, and may be flawed, but has the redeeming virtue of taking responsibility, protecting those who followed, and keeping faith with the best interests of the constituency. In times of crisis, when death seems certain, procedure and legalities fall away and Leadership becomes the law.

In the case of the American defeat at Benghazi, there was a void of Leadership from the outset of the mission to the actual Libyan attack on the diplomatic post.

America has a culture of great leaders

America has a culture of great leaders, and in truth, America is the original and one of the few nations that treats leadership as a discipline, a subject of study within its military. American history has countless examples of great leadership that have become part of our culture. Leadership is not easy, and it is very unsanitary, because if the crisis were neat and orderly, then leadership wouldn’t be needed, it would instead be a matter of clinical and procedural management.

Take the example of the Battle of Gettysburg. General Lee made every conceivable error. He attacked from a disadvantageous position, he allowed his subordinates to hesitate on taking decisive ground, he lost control of his reconnaissance, expended his resources in a fruitless artillery duel, and then, following a fool’s paradigm, he ordered a mass charge of his best Infantry across a death ground that basically handed the enemy a victory. Yet, as his men straggled back—broken and in retreat—in what became known as the epic disaster “Pickett’s Charge,” Lee rode out to them calling out, “It’s all my fault, it’s all my fault!” Lee’s ultimate concern wasn’t his glory, or his ego. It wasn’t to protect his position. It was to preserve the morale of his Soldiers, to allow them to keep their souls intact the best they could after such a defeat, to still believe in themselves during this moment of great failure.

What happened next was legendary. His Soldiers responded with calls of protest. They pleaded with him for one more charge, one more chance at the enemy. They wouldn’t accept that their General was at fault, they wouldn’t allow disgrace on their commander. They’d all die to preserve their Commander’s—and their Army’s—honor.

These same Soldiers and Officers went on to loyally fight for General Lee for two more years, suffering starvation, disease, and the demoralization of a losing war. This is just one of many examples in the annals of American history where we can see that a leader not only shows impregnable moral character, but inspires it among his following, in a way that survives tribulation, and discards controversy. Ultimately, George Washington provides the greatest example of this, having lost-disastrously, six of the nine battles he commanded in, who often raged, and was highly aristocratic in bearing, among a citizen-Soldier Army. Yet, the intangible force was there, and his leadership inspired near fanatical loyalty that makes him the unquestionable Father of this country, hard to fault even in modern academia’s toxic atmosphere of historical criticism.

Yours is the profession of arms, the will to win, the sure knowledge that in war there is no substitute for victory, that if you lose, the nation will be destroyed, that the very obsession of your public service must be Duty, Honor, Country

– GEN Douglas MacArthur

Historically, American Military and Naval leaders have been pretty incredible. American Generals such as Jonathan Wainwright on Corregidor epitomize this. He went into captivity with his men and took the same treatment and punishments that they did, and although his Medal of Honor was opposed by MacArthur, he held no grudge and even stood ready to speak for MacArthur had he won the nomination for president because he believed in him.

These, among many examples, have become the moral foundations of what leadership is among America’s military institutions, taught in all Armed forces leadership schools to this day. The American leader is the parent figure for the troops, the one who makes everything work, the one who provides the vision and by the force of personality and character, sets the tone, and above all, protects the Honor of the troops, absolving them of their sins and defending their actions.

Studying American history we see countless examples of incredible, selfless leadership, often that which is without reward. The result has been a longstanding intuitive understanding – a sort of “social contract”—among American fighting men that they would be expected to pay the butcher’s bill in blood and sin, but that their sacred honor would be preserved by their leaders, and that it is inconceivable America would ever forsake its warriors.

The American Soldier, Sailor, Airman, Marine is unique in the world because he is part of an intuitive fellowship of valor that isn’t taught or emphasized in any training, or in any doctrine. Instead, it is simply understood by every recruit who enters the service, and re-enforced by the cultural values of the institution. No other force in the world maintains this tradition the way America does.

As a nation, however, our understanding of this truth is withering. The military is its own self-perpetuating class system now, and most Americans not only never served, but have no family or friends who have served. This fact estranges the military apparatus from the American political class—a bizarre paradox since the President’s primary role under the Constitution is Commander-in-Chief of the Armed forces. Real leadership, the standing firm in the face of life and death, the strength to hold one’s convictions in the face of controversy, the consistency needed to build faith and trust, and the overall ability to inspire selflessness—qualities that rally the stoutest hearts and toughest of citizens—is sadly unknown to most modern Americans. Rather, today, examples of leaders consist largely of celebrities, athletes, and politicians.

“The attacks in Benghazi did not occur in a vacuum. They took place amidst a severely deteriorating security situation in eastern Libya—a permissive environment where extremist organizations were infiltrating the region, setting up camps, and carrying out attacks against Western targets…”

– Congressional report on Benghazi, II-2

“Probably failing to plan for the day after what I think was the right thing to do in intervening in Libya”

– President Obama, on what constituted the biggest mistake of his Presidency; April 10, 2016

Within the context of Leadership in American history, and the background of the “Arab Spring,” we can best assess Benghazi. We don’t really know what to call it. Not war, not diplomacy, not policy, it is difficult to understand just what the American-inspired “Arab Spring” actually was, personified by the disaster at Benghazi. This is especially true when trying to understand context based on the Congressional investigation, which went straight into the myopic details of the event.

Libya was clearly the decisive terrain for the State Department’s “Arab Spring.” Though they never called it that, they resourced it as if it was. Decisive, in military parlance, means the place or time where you mass power and resources to achieve a marked advantage—basically, that is where you win. On this decisive ground, there was a clear and consistent escalation of attacks from April to August of 2012 against American forces, infrastructure, and personnel that increased in intensity as time went along.

Libya was clearly the decisive terrain for the State Department’s “Arab Spring.” Though they never called it that, they resourced it as if it was. Decisive, in military parlance, means the place or time where you mass power and resources to achieve a marked advantage—basically, that is where you win. On this decisive ground, there was a clear and consistent escalation of attacks from April to August of 2012 against American forces, infrastructure, and personnel that increased in intensity as time went along.

Every American Serviceman who fought in Iraq and Afghanistan, who is wide awake and alert, knows that on the anniversary of 9-11, attacks increase. The Jihadist sees 9-11 as a great victory, and the Jihadist is sentimental. On or about the anniversary of 9-11, American forces change their routines, alter their posture, and even conduct spoiling attacks to offset the inevitable sensational attacks that are usually planned by Jihadists. The security contractors, paramilitaries, CIA agents, and State Department Security Agents (DSS) all knew and understood the gravity of this date, and the foreboding events leading up to it.

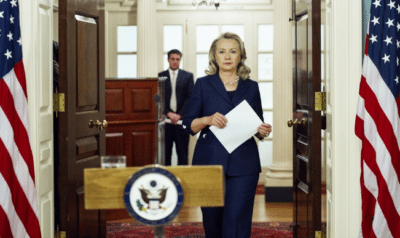

The report proves that these concerns made it all the way to the Secretary of State, Hillary Rodham Clinton. Why was this unheeded? Why weren’t precautions taken? Who was in charge of seeing to this? Were two DSS agents and a team of CIA contractors—all armed with Carbines—enough to protect an American diplomatic post from an unleashed Jihadist militia? Was this small posture so mission essential to warrant the risk?

Many questions arise and interestingly, this time, it’s Congress that raises these questions, instead of the media. The media seemed to back off this debacle as a story, having been much more passionate about this in the premature stages of the investigation. The American media often framed the investigations as mere political infighting—smokescreens—preventing Americans from seeing or understanding the issues.

The American public is generally unaware of what a diplomatic post is, what its loss represents to the world, what the authorities of the various government agencies are, what the authorities of the military are with respect to national security, and the proper way to go about conducting diplomacy and intelligence efforts abroad. These elements explained, the American people can then grasp the issues and their significance, and, in my opinion, understand how Benghazi is an historical stain on America’s leadership, and yet, because of the heroic actions of the men on the ground, a historical glory for the American fighting man.

Man will occasionally stumble over the truth, but most of the time he will pick himself up and continue on.

– Winston Churchill

In the game of chess, a prudent player doesn’t needlessly sacrifice his King or Queen. Modern history bears no facsimile of establishing the diplomatic post in Benghazi, or the mission itself. The truth in this statement stems directly from the House Oversight and Government Reform Committee’s 100-page report. Here, Brian Papanu, the DS desk officer for Libya, told the Committee that host nation security support had been better in the war-torn nation of Liberia than in Benghazi. As he testified:

“Well, Benghazi was definitely unique in almost every — I can’t think of a mission similar to this ever, and definitely in recent history. Potentially the closest I can think of was when we went into Monrovia, but there we had pretty decent host nation support, as far as I know.”

The covert State Department mission—one propelled by the intent to overthrow the government—was, in other words, rivaled by no other facility in recent history. The facility at Benghazi was, at best, ad hoc, and, rather than being an example of expeditionary diplomacy, it was instead, “an expedient [ ] to maintain a diplomatic presence in a dangerous place. The State Department was operating a temporary residential facility in a violent and unstable environment without adequate U.S. and host nation security support.” This is without a doubt, a gross failure of analysis and poor judgment.

The American Ambassador to Libya, John “Chris” Stevens, had been handpicked by Secretary Clinton for the express purpose of sending him into this environment. Although Stevens lobbied for the position, the ultimate choice was Clinton’s. As a career Soldier that spent my time fighting in the Middle East, the prospect of a diplomatic mission in a non-permissive environment where a strategic level position like an Ambassador is exposed to death or capture—is utter absurdity. Even if the mission itself was sound, even if the end state of the “Arab Spring” had been well thought out and articulated, sending an Ambassador to an environment where he could fall into the hands of Jihadists could not have been prudent, and the payoff nowhere near worth the risk in terms of loss of prestige and national humiliation.

The Congressional report details a confusing and nonsensical diplomatic effort in Libya. It goes further to explain why:

“There was no military support for (Ambassador) Stevens’ arrival because of President Barack H. Obama’s “no boots on the ground” policy, no protocol and no precedent to guide his activities, and no physical facility to house him and his team. Stevens’ operation had an undefined diplomatic status and duration, and no authorized set of contacts to work with.”

The context of leadership—moral courage—is about being able to face your boss, behind closed doors, and challenge him. The boss often says to execute anyway. When a leader is faced with this problem, they must either resign, or be loyal and execute. If they choose this course of action, they must mitigate the issues with the boss’s plan in order to make not only the boss successful, but the troops executing it.

However, State Department co-ordinations, risk mitigation, and crisis action planning were suspiciously absent from this ill-fated mission. Once this Ambassador went to Libya, he was, sadly, among a host of enemies, and entirely on his own, similar to a critical piece on the chess board that stands ignored and exposed.

“As-salamu alaikum…Right now, I’m in Washington, preparing for my assignment. As I walk around the monuments…commemorating the courageous men and women who made America what it is, I’m reminded that we too went through challenging periods. When America was divided by a bitter civil war 150 years ago, President, Abraham Lincoln had the vision and the courage to pull the nation together. Now, we know that Libya is still recovering from an intense period of conflict. And there are many courageous Libyans who bear the scars of that battle…I see opportunities for close partnership between the United States and Libya. I look forward to exploring those possibilities with you as we work together to build a free, democratic, prosperous Libya.” – Ambassador Chris Stevens (2012)

In his first official—self-narrated—address to the Libyan people, Chris Stevens memorialized what, to most Americans, is the only interaction we will ever have with the man, the diplomat, the 2012 Ambassador to Libya. Placing partisanship and political talking points aside, as I watched this introductory video—a handshake across time—I couldn’t help but admit that, until September 12th, I had never heard of Chris Stevens. His bravery in the midst of such turbulence and bloodshed compelled me to learn more about him, as well as the compound and its diplomatic status within which his life—and the lives of his family members—were indelibly altered.

As an Ambassador, Stevens was the Chief of the US diplomatic mission to Libya—the highest ranking official representative of the United States to the North African country and the personal representative of the US Head of State, President Obama. Stevens—the eighth US Ambassador to be killed while in office—was the first American ambassador to be murdered on duty in more than two decades, since the 1988 Pakistan airplane crash that killed Arnold Lewis Raphael.

A permanent diplomatic mission is generally known as an Embassy and the head of this mission is the Ambassador. Although Ambassador Stevens was killed at the Benghazi “embassy,” as so many have referred to it, the compound was not an embassy at all and the mission was not permanent. It wasn’t a consulate either. In fact, the Benghazi facility was really composed of two separate US government facilities—a Department of State Temporary Special Mission compound (SMC) and an Annex facility approximately a mile away used by another agency of the United States government.

At its heart, the US effort in Benghazi was a CIA operation, as officials briefed on the operation informed the Wall Street Journal. Of over 30 Americans evacuated from Benghazi on the night of September 11, only seven actually worked for the State Department. The remaining members—case officers, special staff, translators, and analysts—worked for the CIA, using the CIA Global Response Staff (GRS) for security and using the Ambassador and his staff as diplomatic cover.

The two-part and temporary nature of the compound—not an embassy or consulate—is explained in the official reports from the Accountability Review Board and the Senate Homeland Security Committee report:

“In December 2011, the Under Secretary for Management approved a one-year continuation of the U.S. Special Mission in Benghazi, which was never a consulate and never formally notified to the Libyan government.” (ARB)

“The attacks in Benghazi occurred at two different locations: a Department of State ‘Temporary Mission Facility’ and an Annex facility (‘Annex’) approximately a mile away used by another agency of the United States Government.” (Senate report)

As a diplomatic mission, the Benghazi compound falls under the purview of one of the least controversial precepts in international law—that is to say, the inviolability of diplomatic missions, communications and personnel included. Some of the first efforts to formalize this baseline norm took place at the 1815 Congress of Vienna and the 1928 Havana Convention regarding Diplomatic Officers. Articles 22, 27, and 29 of the more modern Vienna Convention on Diplomatic Relations are resolute in their rhetoric:

Article 22. 1.The premises of the mission shall be inviolable. The agents of the receiving State may not enter them, except with the consent of the head of the mission.

- The receiving State is under a special duty to take all appropriate steps to protect the premises of the mission against any intrusion or damage and to prevent any disturbance of the peace of the mission or impairment of its dignity.

- The premises of the mission, their furnishings and other property thereon and the means of transport of the mission shall be immune from search, requisition, attachment or execution.

Article 27.2: The official correspondence of the mission shall be inviolable.

Article 29: The person of a diplomatic agent shall be inviolable. He shall not be liable to any form of arrest or detention. The receiving State shall treat him with due respect and shall take all appropriate steps to prevent any attack on his person, freedom or dignity.

The legal language serves to buttress the historical tradition of the international state system: Diplomats are the agents—the means—the proverbial relations between States, a sentiment that is perfectly captured in the ICJ case of US Diplomatic and Consular Staff in Tehran:

“[T]he institution of diplomacy, with its concomitant privileges and immunities, has withstood the test of centuries and proved to be an instrument essential for effective co-operation in the international community, and for enabling States, irrespective of their differing constitutional and social systems, to achieve mutual understanding and to resolve their differences by peaceful means.”

The Benghazi compound, however, may not have been legally protected with the same safeguards that an embassy or consulate would enjoy. The attack on the Benghazi compound, thus, seems to complicate these international norms of diplomacy. What, on paper, symbolizes a resolute ideal legal norm—a baseline for diplomatic protection—proves to be a far more complex issue amidst the reality of Benghazi.

According to the 39-page report from the Senate Homeland Security Committee, the compound’s initial setup and designation prevented it from receiving some of the key legal protections (both symbolic and tangible) of an embassy or consulate:

“Another key driver behind the weak security platform in Benghazi was the decision to treat Benghazi as a temporary, residential facility, not officially notified to the host government, even though it was also a full time office facility. This resulted in the Special Mission compound being excepted from office facility standards and accountability under the Secure Embassy Construction and Counterterrorism Act of 1999 (SECCA) and the Overseas Security Policy Board (OSPB).”

Such a designation as a temporary, residential facility calls into question whether the mission’s special “non-status” exempted it from State Department security standards and, with it, the Vienna Convention on Diplomatic Relations—a document which governs the establishment of overseas missions.

Furthermore, former U.S. diplomat Thomas Pickering, who led this 39-page probe into Benghazi, also states that, “In December 2011, the Under Secretary for Management approved a one-year continuation of the U.S. Special Mission in Benghazi, which was never a consulate and never formally notified to the Libyan government.” The contents of such an admission directly violate Article 12 of the Vienna Convention, which states:

“The sending State may not, without the prior express consent of the receiving State, establish offices forming part of the mission in localities other than those in which the mission itself is established.”

If this is the case, and given that Chris Stevens reportedly used the Benghazi compound primarily as office meeting quarters, this would make the Benghazi mission a mere arm of the US Embassy in Tripoli, which Ambassador Stevens oversaw. Furthermore, it is clear that the Tripoli embassy—which also served as a consulate—was the primary US diplomatic mission in Libya. A mere two weeks before his death, in fact, Stevens spoke at a ceremony commemorating the opening of the Tripoli embassy’s consular services. As he said, “I’m happy to announce that starting on Monday, August 27, we are ready to offer a full range of consular services to Libyans.”

Overall, the 39-page report’s focus was not on international law. Rather, it came to the conclusion that:

“Systematic failures and leadership and management deficiencies at senior levels within two bureaus of the State Department resulted in a Special Mission security posture that was inadequate for Benghazi and grossly inadequate to deal with the attack that took place.”

Thus, the report directed the blame at the State’s Bureau of Diplomatic Security and the Bureau of Near East Affairs, placing primary culpability on their shoulders.

The diplomatic mission in Libya was vulnerable and juicy prey amidst a sea of sharks, with the sharks swarming brazenly for months leading up to the attack. Yet, no decision makers ever took notice. This mission became a ship sailing into an iceberg, with no one at the helm.

The Congressional report proves, without a doubt, that significant decisions concerning the operation were directly in the hands of Secretary Clinton, who did not question the President’s caveats, or reassess the conduct of the mission in the face of these challenges. Unlike the Congressional hearings, where Clinton stated that Benghazi was one of many diplomatic missions she oversaw and delegated—the Congressional investigation, conducted by Republicans and Democrats alike, showed different. Libya was clearly the main effort for the American State Department.

The Obama Administration had constrained this State Department mission in Libya with severe caveats, limiting military power from lending support to the actual mission, and limiting this herculean role of developing a functioning democracy out of a chaotically violent warzone of Islamic fundamentalism. Even more perplexing is what President Obama stated on March 18th, 2011: America wouldn’t employ ground forces, yet America’s responsibility “was to protect the citizens of Libya.” But with what? The entire nation of Libya was in the midst of chaotic sectarian violence, having just overthrown and murdered their former dictator. Numerous Jihadist militias were jockeying for power, and intense anti-American hatred prevailed, in an explosive atmosphere of rebellion.

To make matters more difficult, bizarre even, the might and prestige of America was presented in the form of a CIA section, a handful of former Soldiers, one Ambassador, and two bodyguards – all in plain sight of the various jihadist factions. It was as if the Obama Administration was repeating the same mistakes made in Iraq. Only in Iraq, the power of the American armed forces was employed to protect the mission there. Now, amidst this environment was a CIA effort comically attempting covert intelligence and source running from their compound in the middle of the city, the only place where heavily armed American men in armored SUVs drove from, meeting various sources in the area. This obviously enticed the conspiracy minded and hostile Salafists/Jihadis, while Ambassador Stevens projected the highest profile possible, preaching democracy, tolerance and all types of Western values that the people of the region resent.

The mission in Libya was a State Department mission. The CIA was subordinate to State. The Congressional report cites emails, recordings, press releases, and interviews where Secretary Clinton was in direct control of the mission. All through the foolhardiness of it, there was no articulated end state other than to “protect the Libyan citizens”—a fact which never seemed to be re-assessed. The diplomatic mission in Libya was vulnerable and juicy prey amidst a sea of sharks, with the sharks swarming brazenly for months leading up to the attack. Yet, no decision makers ever took notice. This mission became a ship sailing into an iceberg, with no one at the helm.

Was “the Military” to Blame?

Where the Congressional report seems to lack analysis, is the confusing relationship “the military” (an abstract term meaning any number of DoD organizations) had in the “Arab Spring” and its situational understanding about the State Department mission in Libya. Some in the media have used this report to deflect blame from the State Department (Hillary Clinton) on the Military. Given the weak political influence the uniformed “military” has, this is an easy target. As usual, there is truth and fiction in the media narrative that is composed in the abstract of understanding the context of true leadership.

What the report does well, however, is qualifying the events leading up to and during the Jihadist attack on the outpost, and listing many indicators that the Jihadists clearly understood that they were attacking to kill the American Ambassador. An initial reaction, one that I personally had as well, was to wonder why US troops were not sent immediately to support the defense of this outpost. The answer to this goes directly back to a failure in Leadership ultimately, but also in that, the very nature of how military forces are postured with respect to America’s global mission and Presidential directives.

What the report does well, however, is qualifying the events leading up to and during the Jihadist attack on the outpost, and listing many indicators that the Jihadists clearly understood that they were attacking to kill the American Ambassador. An initial reaction, one that I personally had as well, was to wonder why US troops were not sent immediately to support the defense of this outpost. The answer to this goes directly back to a failure in Leadership ultimately, but also in that, the very nature of how military forces are postured with respect to America’s global mission and Presidential directives.

To understand how the “military” fits in to this scenario, one must understand five aspects of how the American military is in fact organized throughout the world.

First (anti-militarists may not like to read this), the US Military is actually quite small compared to the tremendous scope it is tasked with. The footprint of the American military throughout the world is in fact a large complex of bases and headquarters that provide the infrastructure to flex the relatively small amounts of combat ready fighting forces that America actually does have.

The immense size of the Department of Defense is indicative of needless corruption, countless ad hoc reserves and National Guard units, and legions of mysterious headquarters that exist primarily on paper in order to collect funding. The actual fighting force of the military is very small.

Second, with respect to ground troops, the US Army, after recent defense cuts, maintains currently 35 Brigades, each numbering 2000 odd Soldiers. Of these Soldiers, about 600 are actual combat troops, the rest performing support functions. Of these 35 “Brigade Combat Teams” (BCTs) only 4-5 at any given time are deployment ready, meaning all the units within the Brigade are trained, validated and filled to their mandated strength.

The third aspect is the Special Operations community, which maintains a slightly better proportion of readiness. Special Operations Forces (SOF) basically project about a third of their Special Forces teams who are in fact deployment ready at any given time, with the other third being on a training cycle, and the other on a rebuilding cycle as the personnel system changes out Soldiers, promotes them out of the unit, people retire, are booted out of the unit, etc. When speaking of a Special Forces team, we are speaking about 12 men. The Navy SEALS are not that much different. While one cannot deny that the SOF operator is in fact a phenomenal Soldier, the prowess of SOF as a capability has become an exaggerated myth in the American lexicon, and true military strategists understand that in battle they are a supporting effort at best.

Qualitatively, the American armed forces, in reality, are stretched very thin, performing a multitude of tasks beyond their scope, and subject to the whims of a statistic-oriented personnel system that is the enemy of unit cohesiveness. Every deployable unit in the American armed forces is committed to a real world mission.

The fourth aspect of understanding the American military posture is that only the Marine Corps maintains a rotation of deployable forces as a “9-11” force, so to speak. These units consist of three deployed, ship bound Marine Expeditionary Units (MEUs) two of which deploy to the Pacific, and the other to the Mediterranean. Having served on a MEU, I can personally speak to the reality of its capabilities. The Marine Corps rotates a selected combination of its forces to support each MEU’s mission, these are: one of its twenty Battalions of Infantry (800 men), one of its twenty Batteries of Artillery, (6 Howitzers, 220 men) one or two of its sections of attack helicopters (two Cobra gunships) and one of its 18 platoons of tanks (4 M1 Abrams) in and out of these MEUs who in turn, rotate throughout these ship born deployments.

In theory, a MEU can project one Company within this force (200 men) into anywhere in their area of operation within 24 hours, and then be supported by follow-on forces, which sustained by the MEU and the Navy’s Amphibious Ready Group (ARG), can carry on thirty days of combat operations. Each region has three MEU headquarters that run on a 6-month deployment cycle, 6 month train up, and 6 month refit period. Had the Benghazi debacle been foreseen, either the 22nd, 24th or 26th Marine Expeditionary Units, whichever one was deployed to the Mediterranean at that time, could have been postured off the Libyan shore and easily crushed this attack, if not deterred it by its presence.

However, the call to do this would have had to have come at least a day prior, and in actuality, three days to provide the Marines with the time to plan and organize effectively. A MEU would not have had direct communications, in the form of tasking authority, coming from the US Diplomatic mission themselves. Also, a MEU would not have had the authority to “color outside the margins” because its purpose is to support the Navy. It has its missions laid out for them long before they even are slated to deploy.

A MEU Commander, or the Commodore of the Navy’s ARG, would be sacked on the spot if they were to deviate from their tasks, as the strategic reserve of the United States, without it being cleared by the Combatant Command of the region they operate in. The Combatant Commander briefs the President and Secretary of Defense on these deployments monthly, and gains their approval. In short, to alter the mission of Marine Expeditionary Units is a national level decision that, if turned on a dime without Presidential level approval, would likely cause the ruin of many military careers. When a four star General is sacked, his staff, and subordinate commanders’ careers die with him. In today’s era, for whatever reason, the Administration has arguably sacked more Generals/Admirals than any other President in American history, and this point is not lost on the Flag level leadership in the American Armed Forces.

Then, there is the subject of awareness concerning the gravity of the situation in Libya and the timing thereof. This brings us to the fifth and final aspect of America’s military posture, the Combatant Commands. These are the ultimate entities responsible for situational awareness in the world’s regions.

The American Armed Forces are postured throughout the world by a system of “Combatant Commands” that are commanded by a Four Star General. The staffs of these Commands maintain expertise on that particular region. Africa Command, or “AFRICOM” was the command, based in Europe, which oversees American military operations on the continent of Africa. Like all the other Combatant Commands, and like a Marine Expeditionary Unit, AFRICOM has no organic forces; it’s basically one of the many headquarters throughout the Department of Defense without troops. Like other Commands, it’s a staff of analysts, operations officers, and logisticians, who take control of forces merely lent to them for the purpose of American missions in Africa. The mission of AFRICOM is almost entirely intelligence collection and analysis, with some local nation support and training by Special Operations Soldiers, all oriented on inspiring corrupt and incompetent African governments to kill Jihadis in sub-Saharan Africa.

Upon reflection, one can surmise the incredulity that the AFRICOM staff must have felt upon witnessing the “Arab Spring” and how this action was in fact creating legions of Jihadists while they struggled to destroy Jihadists to the south. In short, AFRICOM possessed no organic ground troops, least of all ones that were ready to respond as a quick reaction force in Libya, and as a headquarters, was, in every definition, scope and purpose, disjointed from the bizarre democracy-building mission in Libya.

Therefore, when this crisis occurred, the Commander of AFRICOM, General Carter Ham, reached out to an asset that was agile enough to support the embattled CIA Contractors and Diplomatic Security Agents. This was the Marine Corps Fleet Anti Terrorist Security Team (FAST), which is basically a re-enforced Rifle Company that has the luxury of not being burdened with the plethora of tasks indicative to a regular Company, and resourced with time, money and equipment to hone itself into a highly proficient fighting force. The traditional role of FAST is to deploy in support of Naval forces (mostly nuclear) that may experience terror attacks. FAST belongs to the European Combatant Command (EUCOM) by way of Marine Forces Europe command (MARFOREUR). They were not even under General Carter Ham’s AFRICOM.

What it seems General Ham did was expedite protocol to order FAST to stand to, diverting them from their mission to protect American nuclear assets in the Mediterranean, and prep them to enter into harm’s way with little or no understanding about the situation on the ground in which they were going to fight.

The subject of FAST’s employment is where the Congressional report fails, and where the apologists attempt to exploit by deflecting blame on the Military. Significantly, the readiness of FAST was examined as if FAST was already aware or in anticipation of this mission. I have no doubt that many members of FAST, especially their leadership, had any idea that there was a “covert” CIA/Diplomatic mission in Libya, and least of all its officers, men in their early to late 30s who were no doubt taken aback by this unorthodox and mysterious order.

In addition, FAST doesn’t have its own airlift, another time-consuming coordination that needed to be made. A military force that goes into combat is not the same as dialing 9-11 and getting a squad car. Planning, prep and coordination has to be made. Combat is a storm of chaos in which rushing just gets people needlessly killed. The fact that America, in the modern age, can project combat power in less than a week is astronomically beyond the capabilities of most other nations. The only way a military force could have been ready in time is if they were already on the ground in Libya, and had enough combat power to fight their way to the “outpost” in Benghazi.

The State Department’s mission in Libya was never on AFRICOM’s list of responsibilities. In fact, it had been forbidden territory for their entire DoD based on President Obama’s caveats, and the reluctance of the State Department to involve the military. To deflect blame on General Carter Ham, the military commander completely removed from the inner workings of the Obama Administration, and who had no involvement in the Libya mission, and further, had no forces organic to his command that could have helped, is like whipping a stray dog for something the neighbor’s cat did.

The Nation that makes a great distinction between its scholars and its warriors will have its thinking done by cowards and its fighting done by fools.

– Thucydides

The American people should have high expectations for their leaders and their abilities to succeed. Failure should not be within America’s span of tolerance for those they elect to lead.

The evidence of State Department failure in leadership at Secretary Clinton’s very own level is impossible to skirt around. The Congressional report published numerous interviews in Appendices I and K showing that credible figures within both the military and the intelligence community, as well as communiqués from within the State Department, made Hillary Clinton aware of the vulnerability of her people in Libya, as well as the unsoundness of the mission itself.

The State Department’s own internal quarterly review wrote alarming critiques about how it conducts missions abroad. Interestingly, the State Department under Secretary Clinton rejected the findings of its very own review, findings that were validated by the debacle at Benghazi. The summation of interviews that were synced with the timeline of events show a remarkable awareness and consensus of all involved in the Libya mission that this was an incredibly flawed and misled operation. This is shown in the Committee’s recommendations, keeping specific testimonies confidential.

Interviewed were 21 Diplomatic Security Service special agents who served in Benghazi at varying times, a plethora of foreign service officers and dozens of applicable leaders in the administration, such as David Petraeus. None of these accounts led to recommendations that demonstrate any evidence that the State Department handled this mission in a suitable manner. The recommendations in part V of this report belie any notion of competency as high up as the Obama Administrations methods for receiving and analyzing information, to the very abilities of the operators within the Administration and State Department itself.

Unfortunately, the Congressional Committee reveals a lack of understanding toward military employment in the region, and recommends things to the DoD that are not in keeping with the priorities set down for these units. To re shift these units as quick reaction forces as the committee’s recommendations suggest, they would have had to be pulled off the missions they were already on.

During the hearings, Secretary Clinton repeatedly mentioned the involvement of other layers of management – “security experts” – and various departments within State, which were somehow at fault. With all the deficiency in her organization, she alleged she was poorly advised, misled, and unable to rely on any of her subordinates, all while saying she “accepts responsibility.” The Committee’s report does not point to or specifically name subordinates as failures in spite of dozens of exhaustive interviews.

The report makes an effort typical to bureaucracies, which is to proclaim systematic issues as a way of protecting individual failure. However, this is about the State Department of the United States of America, and not some start-up corporation. These many systematic issues, basically making the extreme case that the most senior leadership completely lacked any situational understanding of their most high priority mission, and the inability of the entire diplomatic, intelligence and military apparatus to communicate issues to the State Department’s leadership, goes well beyond a systematic issue. The report of course, addressed the many, many inconsistencies made by Secretary Clinton, with unblinking hesitation, proven by incriminating emails.

The report makes an effort typical to bureaucracies, which is to proclaim systematic issues as a way of protecting individual failure. However, this is about the State Department of the United States of America, and not some start-up corporation. These many systematic issues, basically making the extreme case that the most senior leadership completely lacked any situational understanding of their most high priority mission, and the inability of the entire diplomatic, intelligence and military apparatus to communicate issues to the State Department’s leadership, goes well beyond a systematic issue. The report of course, addressed the many, many inconsistencies made by Secretary Clinton, with unblinking hesitation, proven by incriminating emails.

America is not going to ignoble its span of understanding concerning character and leadership anytime soon. After the Benghazi attack, the Administration ordered the abandonment of the Libya mission as quickly and flippantly as it ordered the execution of it. Mostly Americans of military backgrounds saw the many inconsistencies with this, which was seized upon by the Republican Party, in conjunction with Democrat Tammy Duckworth (a former Army Aviator who was wounded in Iraq). To date, there has been no estimation at the cost to American national prestige that the Libya mission, or “Arab Spring,” as a whole incurred. There is no defense of Hillary Clinton’s performance that is in keeping with the standards of ethics and leadership expected by an American leader at not only the national level, but every other level downward.

My conclusion upon reading, and re-reading this report is that the State Department was in fact leaderless, and was flippantly engaged in activities beyond its scope and capabilities, for reasons only known to President Obama and Secretary Clinton.

When things go wrong in your command, start wading for the reason in increasing larger concentric circles around your own desk.

– General Bruce D. Clark

In conclusion, the American Diplomatic mission in Libya was a national disgrace that exemplified the incompetency that has become symptomatic of the post Cold War American political class. The American Department of State, led by Secretary Clinton, receiving the typically conditional support of the CIA, embarked on a campaign of regional subterfuge, grossly underestimating the required assets for this mission, giving no clear purpose or end state and no military support, and with complete disregard for the anti-American temperament in the Middle East. There is no indicator that Clinton ever mitigated the risks caused by the severe caveats placed upon her mission by the Obama Administration.

Throughout the course of this mission, no one was at the helm to assess, make decisions or coordinate for help. Monitoring this mission’s success or failure in any way was conspicuously absent as a “lord of the flies” environment arose on the ground in Libya.

And upon this mission’s failure, causing a stunning and almost unparalleled blow to American prestige, Secretary Clinton refused any real responsibility.

As the phoenix rises, one thing is certain: a new culture of Leadership must rise from the ashes of Benghazi.

Joseph Labarbera, for Lima Charlie News

Joseph Labarbera (USMC, U.S. Army) served as Command Inspector General at Ft. Irwin, California. Joe served 54 months combined OEF/OIF, with 46 months of combat in the Army’s 10th Mountain Division throughout Afghanistan and Iraq.

![A Trump war crime pardon dishonors us all [Lima Charlie News]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/A-Trump-war-crime-pardon-dishonors-us-all-Lima-Charlie-News-480x384.png)

![Image Imagine a Global Space Community ... The Space Foundation Can [Lima Charlie News][Graphic by Anthony A. LoPresti]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/Space-Foundation-Space-Symposium-Lima-Charlie-News-480x384.png)

![Africa’s Elections | In Malawi, food, land, corruption dominate [Lima Charlie News]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/Malawi-election-Food-land-corruption-480x384.jpg)

![Image The Rwandan Jewel - Peacekeepers, Conflict Minerals and Lots of Foreign Aid [Lima Charlie World]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/Rwanda-Jewel-480x384.jpg)

![Image [Women's Day Warriors - Africa's queens, rebels and freedom fighters][Lima Charlie News]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/Womens-Day-Warriors-Lima-Charlie-News-480x384.jpg)

![Image Zimbabwe’s Election - Is there a path ahead? [Lima Charlie News]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/Zimbabwe’s-Election-Is-there-a-path-ahead-Lima-Charlie-News-480x384.png)

![[Silver lining for China in Zimbabwe’s violent elections][Lima Charlie News]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/Screen-Shot-2018-08-02-at-12.51.35-PM-480x384.png)

![A Trump war crime pardon dishonors us all [Lima Charlie News]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/A-Trump-war-crime-pardon-dishonors-us-all-Lima-Charlie-News-150x100.png)

AWESOME article, Joe !!!

Great Writing Skill; Great Report!!

Thanks for your Service!!