With the subtle and clandestine methods of ‘hybrid warfare’ available to any nation, from disinformation to influence operations to election interference, Russia and China continue to be very creative. Some argue that amid the increased onslaught of hybrid warfare tactics by Eastern powers, Western style democracies are facing a threat of extinction. But what is the tipping point, where push comes to shove, when an ally is facing more than just a domestic problem, and a nation is “under attack”? And if such an “attack” involves a member state, or partner, at what point would NATO intervene? The following is an OPINION piece by Håkan Gunneriusson. – Editors

The term Hybrid Warfare has evolved over the years. Originally it defined irregular non-state actors with advanced material capabilities. A prime example, and what popularized the term, is Hezbollah’s activities during the 2006 Israel-Lebanon War. During that conflict Hezbollah successfully engaged the highly-advanced and well funded Israeli Defense Forces utilizing a host of different missiles, technologies and tactics that the IDF was simply ill-equipped to deal with.

Since then, the term has morphed into meaning conceptual warfare, involving a blend of approaches, from conventional warfare to the polar opposites found in irregular warfare and cyber warfare. A recent RAND Corporation funded study states that while the term has no consistent definition, it generally refers to “deniable and covert actions, supported by the threat or use of conventional and/or nuclear forces, to influence the domestic politics of target countries.”

Author Peter Pindják wrote in NATO Review that hybrid conflicts “involve multilayered efforts designed to destabilise a functioning state and polarize its society.” Pindják writes that unlike conventional warfare “the ‘centre of gravity’ in hybrid warfare is a target population [where] the adversary tries to influence influential policy-makers and key decision makers by combining kinetic operations with subversive efforts.” This can even include the collective and organized generation of “fake news” or engaging in election interference.

Hybrid warfare is not about translating a national doctrine to see if the exact wording is found in the tomes of text. Instead one has to look towards the actions of the nation-state and its agents. The virtue in using such terminology and approach is to avoid being limited by archaic concepts and their historical connections or conjugations, and to avoid becoming bogged down in academic discussion with little relation to current developing events.

Necessity is the mother of invention

Two countries always occupy the discourse when it comes to innovations in hybrid warfare; Russia and China.

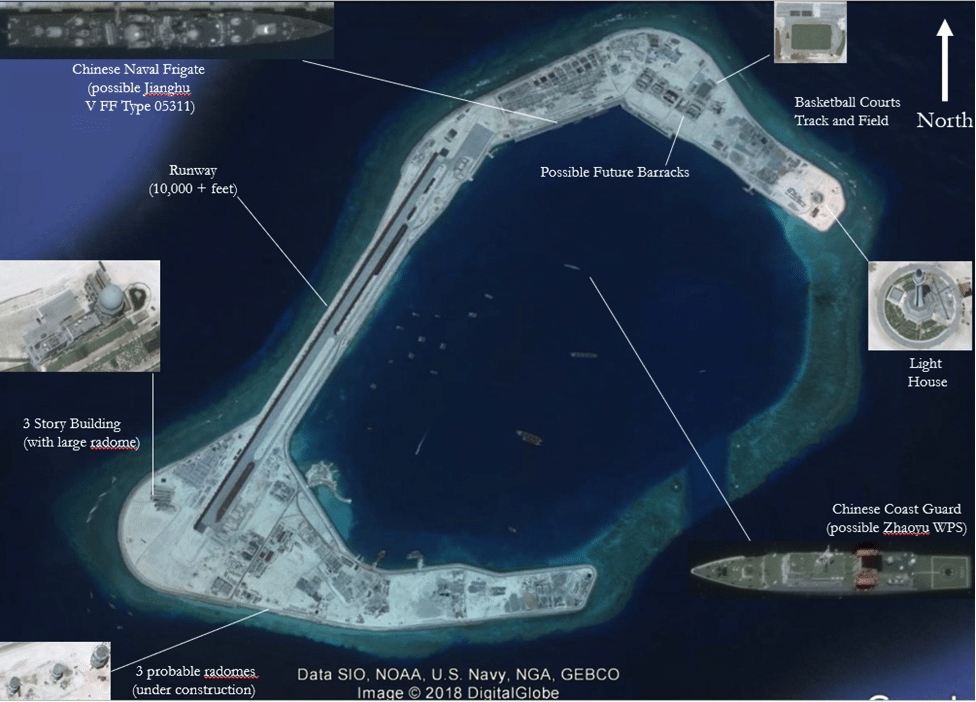

One such recent example is the weaponizing of the maritime environment through “terraforming” as part of a multi-pronged offensive. Lima Charlie News has written extensively about China’s construction of an expansive network of artificial islands in the disputed South China Sea. Last year China’s Defense Minister, Wei Fenghe, stated, “The islands in the South China Sea have long been China’s territory. They’re the legacy of our ancestors and we can’t afford to lose a single inch of them.”

Officially, China claims that the intent behind the islands is strictly commercial — yet they are being used as de facto weapons in China’s regional gunboat diplomacy.

![Image South China Sea China construction [Janes]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/South-China-Sea-China-construction-Janes.png)

In Russia’s case, immediately following the annexation of Crimea in 2014, Russia began the planning and construction of the Crimean Bridge over the Kerch Strait in Ukraine. With the opening of the bridge in May 2018 (also called the “Unification Bridge”), tensions have continued to rise with Ukraine.

On November 25, 2018, Russian ships attacked and boarded three Ukrainian vessels in the Crimean port of Azov near the Black Sea. The Ukranian vessels were attempting to break through an unofficial blockade organised by Moscow seeking to disrupt Ukrainian access to the Sea of Azov via the Kerch strait by placing a fully loaded oil tanker ship beneath the bridge.

On February 18-20, 2019, in the Sea of Azov, close to the Kerch Strait, Russia closed an area of the sea for navigation due to military exercises with live fire.

In both the cases of China and Russia, these actions are illegal and offensive by their very nature. What is yet more unsettling, these are also examples of what can be seen as the 7th generation warfare, hybrid warfare.

Neither Russia nor China use the term “hybrid warfare” as a doctrinal word. This has led some experts to argue that these nations don’t subscribe to the strategy, such as British academic and Russian affairs observer Keir Giles.

With this debate in mind, Russia seeks to avoid the classification of its actions in Ukraine as armed conflict in its legal and political form. This despite the fact that Russia has and continues to launch warfare at an impressive scale. Evidence of Russian troops and material in Ukraine is obvious. Yet, it is clear that the West prefers to look the other way as no one really wants open war with Russia for what is perceived to be at stake.

Far reaching consequences

I would argue that something much bigger is at stake. I have written extensively about hybrid warfare as a reflexive control, as an example of the long-running asymmetrical duel between Russia and the West.[1] Reflexive control refers to a Soviet war stratagem which seeks to manipulate and utilize the mind of the adversary in order to create or expose vulnerabilities. European operators are more primed by the logic of globalization and the creation of a unified fellowship than by the autonomous political doxa of specific national policies.

Vladimir Lefebvre, the renowned Russo-American mathematical psychologist, defined the term reflexive control as “a process by which one enemy transmits the reasons or bases for making decisions to another”.[2] This is not a new concept, but rather a familiar one for students of sociology. For example, social theory has shown that through well-placed agents an operational area can be modified before any form of offensive to create a beneficial predisposed situation for friendly forces.[3] Such preparations, to soften the proverbial ground long before any overt actions are taken, are key aspects in a hybrid warfare offensive.

The actual consequences of Russia’s hybrid warfare are far-reaching. Russia’s actions, which can be quantified and qualified by the value of its actions, disrupt the Western narrative. This creates an untenable situation where the West represents rather than stands for its own values. Fundamentally, this undermines the international system, which the West is meant to support. If this continues, it will lead to the system, and its values, being replaced step-by-step by another system, one which serves Russia, China, and any other actors that may correlate with the policies of these countries.

Eventually emerging Asian powers, predominantly China, feel little reason to pay attention to, much less align themselves with, an “outdated” Western system. Particularly when the West is unable or unwilling to fill its proverbial shoes on the global stage.

Empirically we do not find much new with Russia’s present-day warfare. At least when viewed out of a historical perspective. The past hundred years of Russian history alone holds a magnitude of acts revolving around aggression coupled with deception and obfuscation, or maskirovka. But unlike in the past, today Russia might very well get away with acting in such manner.

Terraforming the maritime environment as Russia and China have done is an aggressive practice. The fact that Russia, and China along with it, can act in such a fashion signals something new and troublesome. This is about the West not standing up for core democratic values and international systems, which Russia is actively playing upon.

Thus, it is paramount to think of these developing conflicts, and the decisions made therein, as matters of life and death for the West.

Russia is using Ukraine as a proverbial canary in the coal mine, to see how NATO responds. NATO’s inaction can then be translated and implemented in the Baltics.

Ukraine – A test subject

Russia is waging a war of aggression in Ukraine, a fact that Western politicians are unlikely to acknowledge. Regardless of how much proof there is to support that statement, acknowledging the state of war in Ukraine would lead the West onto a rocky road. The Nüremberg principles would come into play. With those principles enacted, the international community’s responsibility to enter the fray would be unquestionable.

At the same time, the formalized instruments of international law and institutions are often, much like Lady Justice, blind to the realities taking place. Russia has multiple venues and methods to block or delay efforts to create a coordinated international response. For example, Russia could utilize its veto power in the United Nations Security Council, regardless of the prohibition of the use of force in Article 2 (4) of the UN Charter. The International Court of Justice (ICJ) in The Hague, the principal judicial organ of the UN, is built on the fact that only states can be parties to cases and jurisdiction is dependent on consent (e.g. Marshall Islands cases). The International Criminal Court (ICC) requires that a key state be a member of the institution, which Russia and China are not (nor the USA for that matter). The Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) Court of Conciliation and Arbitration is all but forgotten and thus hard to activate in a practical way and then only for European matters.

The West’s primary weapon, one that it often elects to utilize when a nation-state acts out of alignment with Western interests, is the imposition of sanctions. Realities have shown, however, how pointless sanctions can often be.

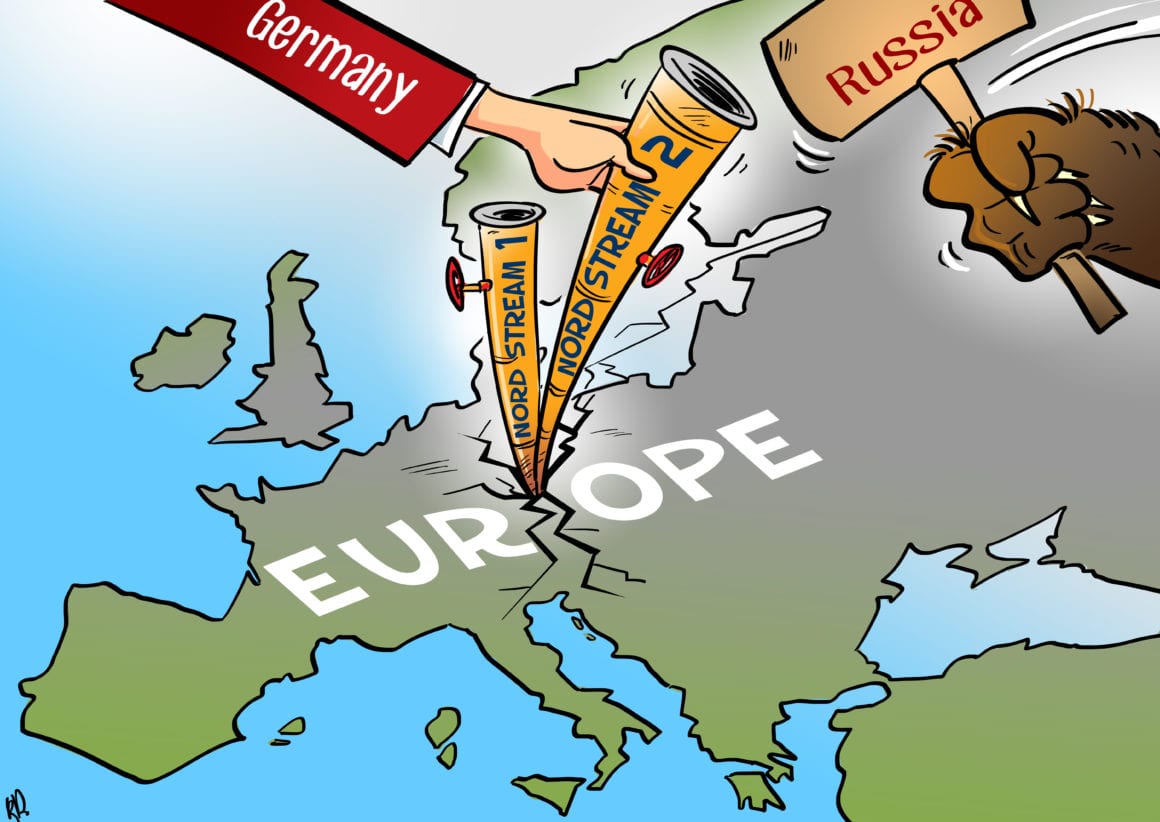

The sanctions imposed on Russia do not truly deal with Russia’s premier hybrid warfare weapon — the energy sector — and thus do little to rob Russia of its contemporary warfare capabilities. It is the energy sector, along with aggressive weapons exports, that enables Russia to engage in such a successful offensive. The enactment of truly functional sanctions against Russia’s energy sector, a cornerstone of its national economy, would have a detrimental effect on Russia’s abilities.

The amount of natural gas exported from Russia to Europe is at an all-time high. It shows little sign of slowing down despite political concerns from the European Union (EU). Soon, Russian natural gas exports to Europe will increase further with the impending completion of Nordstream 2 in the Baltic Sea. This massive project, with the support of German politicians, has been enabled despite the fact that presently active Baltic pipelines are yet to reach full capacity. [4] Germany, the economic engine of Europe, has made itself dependent on Russian energy, just as it is scaling down its own energy production of domestic coal and nuclear energy.

With this reality in mind, it has become obvious that the willingness to meet Russian or Chinese interests using suitable means is very distant. No nation, including Ukraine, wants an open armed conflict with Russia. ASEAN-countries, wedged between the giants India and China in the South Chinese Sea, are in much the same situation.

Nor does Russia or China expect an armed conflict with the West in the near future. This is a reasonable assumption, which has been weaponized at the political-strategic level. A direct result is the weakening of international systems and organisations which support Western style democracies. The West’s cohesive ability to actually meet the Eastern offensives is eroding each day. NATO and the EU are both facing internal strife to the point where external threats have been ignored.

This, in turn, creates the perfect environment for Russia and China to offer their authoritarian systems as drop-in replacements. Considering the vast number of failing democracies, pseudo-democracies or even outright authoritarian regimes presently operating across the globe today, the number of potential recruits for the Russian and Chinese spheres of influence is not one to be ignored.

Those opting for a “peace in our time” approach often point out that Ukraine is not a NATO country, but rather just a NATO partner. This means that article 5 in the North Atlantic Treaty relating to collective self-defense doesn’t apply to Ukraine.

If Russia’s hybrid warfare tactics in the Baltics are perceived as simply a domestic problem rather than an overt Russian attack, NATO member states could not invoke the collective defense implementation of Article 5. NATO would once again be presented with the opportunity to look the other way while a NATO-member state is essentially under attack.

This eventuality is one that several Baltic military strategists and researchers have looked at.

Perhaps the best study was that carried out by Janis Berzins at the Center for Security and Strategic Research of the National Defence Academy of Latvia in April 2014. In his paper, entitled “Russia’s New Generation Warfare in Ukraine: Implications for Latvian Defense Policy” he stipulates that this scenario is not just likely, but is likely already taking place.

If this is allowed to transpire, NATO itself would be in real and present danger due to its inaction.

Of course, a single NATO or UN member can still act unilaterally, likely sustaining intense public scrutiny in the process. The likeliest candidate would be, if history is any judge, the United States of America. Such an act could, theoretically, force European NATO member states with a strong allegiance to the US to follow suit, lest they wish to face a situation where their own protection by NATO becomes endangered, and a domino effect takes place. But in the current pan-NATO political environment, such a series of events appears unlikely.

It is far more likely that all NATO members would continue to turn a blind eye towards the emerging situation, until it’s too late.

Håkan Gunneriusson, for LIMA CHARLIE WORLD

[Edited by John Sjoholm and Anthony A. LoPresti]

[Subscribe to our newsletter for free and be the first to get Lima Charlie World updates delivered right to your inbox.]

Håkan Gunneriusson is Associate Professor (Docent) in War Studies at the Swedish Defence University and has recently been research fellow at NATO Defense College, Rome. He also holds a position as Visiting Research Fellow at the center of Conflict, Rule of Law and Society, Bournemouth University. He served in the Swedish military. The views expressed here are his own.

Lima Charlie World provides global news, featuring insight & analysis by military veterans, intelligence professionals and foreign policy experts Worldwide.

For up-to-date news, please follow us on twitter at @LimaCharlieNews

SOURCES

[1] H. Gunneriusson and S. Bachmann, “Western Denial and Russian Control. How Russia’s National Security Strategy Threatens a Western-Based Approach to Global Security, the Rule of Law and Globalization”, Polish Political Science Yearbook, 46(1), 2017; S. Bachmann and H. Gunneriusson “Russia’s Hybrid Warfare in the East: Using the Information Sphere as Integral to Hybrid Warfare”, Georgetown Journal of International Affairs – International Engagement on Cyber, V: Securing Critical Infrastructure, 2015, pp. 198-211.

[2] Thomas, L.T., (2004). “Russia’s Reflexive Control Theory and the Military”. Journal of Slavic Military Studies, 17 pp. 237 – 256.

[3] Håkan Gunneriusson, Bordieuan Field Theory as an Instrument for Military Operational Analysis. Basingstoke, Palgrave Macmillan

[4] The Russian owned gas pipeline Nord Stream also creates an incentive for Russia to possibly intervene in the Baltic Sea region. Gazprom does for example own 51% of Slite harbour on the Swedish island Gotland in the Baltic sea. SvD (“Nordstream storsatsar pa Gotland”, 2016 November 27). Gotland is a large island (3184 km2) which in itself is an unsinkable carrier in the Baltic Sea and dominates the SLOC to the Baltic.

In case you missed it:

![Image Russia and China’s 'hybrid warfare' - Does the West even care? [Lima Charlie News]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/Russia-China-Hybrid-Warfare-02.png)

![Blossoming Russo-Turkish alliance leaves U.S., NATO behind [Lima Charlie News]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/Russia-Turkey-alliance-leaves-U.S.-NATO-behind-480x384.png)

![image NATO’s value can’t be measured in nickels and dimes [Lima Charlie News]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/NATO-Trump-0005-480x384.png)

![Image Memorial Day may soon be a remembrance of democracy and those who had the courage to defend it [Lima Charlie News]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/Memorial-Day-may-soon-be-a-remembrance-of-democracy-and-those-who-had-the-courage-to-defend-it-Lima-Charlie-News-480x384.png)

![The Mind of Bolton - AUMF and the New Iran War [Lima Charlie News]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/Inside-the-mind-of-Bolton-Lima-Charlie-News-main-01-480x384.png)

![Blossoming Russo-Turkish alliance leaves U.S., NATO behind [Lima Charlie News]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/Russia-Turkey-alliance-leaves-U.S.-NATO-behind-150x100.png)