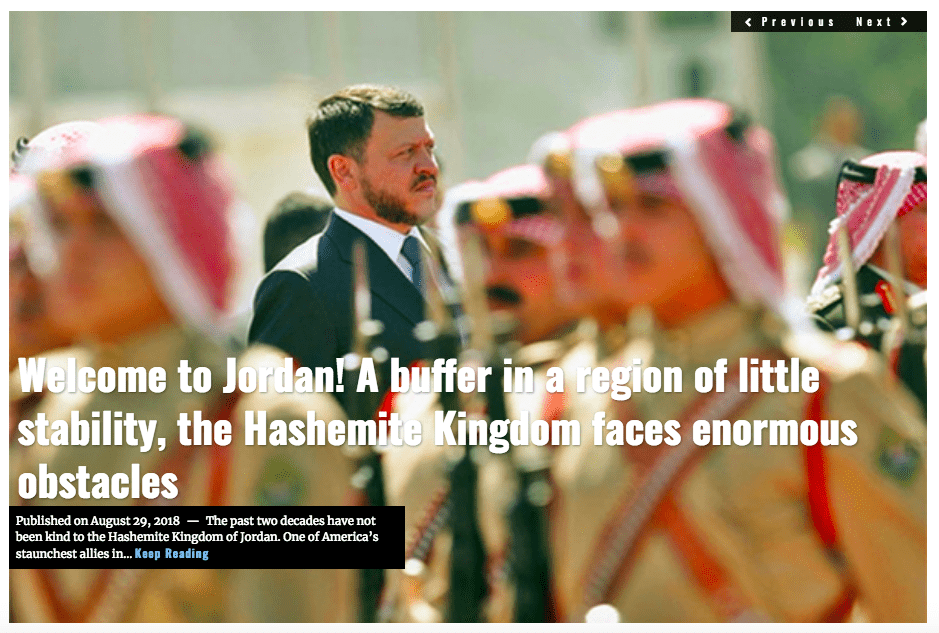

Trapped in a game of geostrategic chess, Jordan stands as a buffer in a region with little stability. Part 3 of a 3 part series. [Part 1 | Part 2]

The Jordanian economy is beyond crippled and is heading towards insolvency. Amidst a weakening financial state across the region, a burgeoning refugee crisis, a broadening set of civil and uncivil conflicts, with Western allies exhausted, a severe crisis dominates the Kingdom.

Jordan held $19 billion in foreign debt in 2011, which represented 50 per cent of its GDP. By 2016, foreign debt had reached $35.1 billion, representing an astonishing 93 per cent of its then GDP. The cause for Jordan’s continuous borrowing has been primarily attributed to the high cost of being at the maelstrom of an increasingly unstable region. This, in turn, has lead to noticeable increases in military expenditures, combined with decreased foreign investment, trade and tourism.

Economy, Tourism and Terrorism

The stresses upon the Kingdom are amplified by the fact that Jordanian unemployment figures are officially over 18.5 per cent, as of 2017, with a disheartening 75 per cent of young graduates being out of work as well. The shadow numbers of unemployment appear even higher, indicating that the actual figure is closer to 23 per cent. In 2014, the poverty level, defined as one who lives on less than $5.5 dollars per day, climbed above 20 per cent. That number was brought down to 18.1 per cent in 2017.

Based on the 2015 census, the most recent one to date, one-third of the country’s population are refugees from war-torn neighbouring nations. Jordan seeks to portray itself as a proud, welcoming, and resilient society amidst turbulent waters in an increasingly unstable region. But such an outlook is not enough to sustain a nation that is amongst the region’s fastest growing in population while experiencing an increasingly stagnating economy.

The Jordanian Gross Domestic Product (GDP) has steadily decreased from its 2008-2009 high ten-year index point, from an astonishing 8.25 per cent in 2008-2009 to an alarming projected sub 2 per cent in 2018. In more relative dollar amounts, this represents a mere doubling of the national GDP from 2008 ($21.97bn) to 2018 ($40.07bn). While this remains a positive development in the overall economy, it is far from an agreeable development considering the growing number of people within Jordanian borders. That makes the GDP per capita equivalent to 26 per cent of the world’s average.

Jordan has on numerous occasions attempted to introduce much needed, albeit highly unpopular austerity policies, in 2011, 2014, 2016 and 2018. Its people have refused each one, with emotionally charged protests in urban centres and rural areas alike, causing disruptions to traffic and public services. For economic observers and analysts, it appears that the Jordanian population, much like the populations of Greece, Italy and Cyprus, are at times cheering the country onwards, towards the edge of the cliff. The emotional outbursts of demonstrators led to the replacement of more than one government upon the King’s order, in 2011 and again in 2018, as it has implemented much-required austerity policies to try to resolve the growing debt crisis.

When goods cannot cross borders, armies will.

- Frédéric Bastiat

Between 2011 and 2016, Jordan saw a 72 per cent drop in tourism, resulting in a 50 per cent drop in tourism-related revenues. In 2016 it began to rebound after a massive public relations campaign carried out by the Tourism Board agency, only to take yet another hit later that year as a series of terror attacks happened over the span of six months.

A weak economic state, resulting in high unemployment rates and several unpopular attempts at introducing austerity policies, have all functioned to fuel underlying anger and dissatisfaction ordinary Jordanians have towards their lot in society. Jordan’s rulers and politicians have also faced deep resentment as the population has lost confidence in the ability to keep the nation safe. All factors that might, in turn, risk tipping the country into a cycle of instability that is regrettably common in this part of the world.

As a stopgap measure, neighbouring Saudi Arabia stepped in with an aid package to the tune of 2.5 billion dollars. Ultimately the aid package will not remove the underlying problems, where the Jordanian expenditures far outweigh its revenues, unless stern austerity measures are taken. This is likely to happen within the next five years and will be followed by the outrage of the people.

Yet, Saudi Arabia did not provide the $2.5 billion simply to stabilise the country’s economy. Its main reason was pure geostrategy. In an era where sectarian rifts are widening and low-intensity conflicts are unending, Saudi Arabia needs a buffer to protect it from the rest of the region.

“I’m proud of what I’ve done in Jordan, but the region itself is sitting on a time bomb.”

-King Hussein of Jordan

It is in this backdrop that Jordan has seen a dramatic increase in extremism within its borders. While foreign extremists have caused the majority of violent clashes, that is quickly changing. Where militant extremists used to originate primarily from Salafist Jihadi movements, such as al Qaeda, it is becoming evident that a noticeable and growing minority in the country are now favouring the surging number of religious militant groups that deem al Qaeda and its affiliates too liberal.

This can be seen in the increasing number of radicalised Jordanians returning from the various regional hot spots. Many of these have fought against governments or other groups to create or preserve the existence of a Shari’a-based state. With their return, local Jihadist movements that are less radical find that their viewpoints are now incompatible, resulting in the loss of dedicated followers and the disassociation from the old leadership of more mainstream Jihadist leaders, such as al-Maqdasi and Abu Qatadah. As a result of this, more radical groups are finding Jordan fertile land to recruit from.

Jordan has, for a long time, been a reliable recruiting ground for more traditional Jihadist entities. However, the new and more extreme generation of Islamist organisations is quickly gaining favour. This has caused severe problems for the Jordanian security apparatus as it has not yet managed to adapt, adopt, and apply suitable strategies to meet these new challenges. While the Jordanian intelligence community has managed to penetrate the domestic groups in their entirety, the newer organisations are much more disassociated from central leadership. They are operating towards a loosely held idea of a common goal, and thus making it significantly more difficult to infiltrate to a useful level.

Over the nearly two decades that have gone by since the beginnings of the Global War on Terror, Jordanian society has produced several prominent Islamist extremists, a majority of which have been al Qaeda affiliated. Abu Musab al-Zarqawi oversaw the creation of al Qaeda insurgency in Iraq. Doctor Humam Khalil Abu-Mulal al-Balawi is the man that carried out the infamous suicide bombing on Camp Chapman in Afghanistan, killing seven American Central Intelligence Agency officers and contractors, an officer of Jordan’s General Intelligence Directorate, and an Afghan working for the CIA. al-Balawi’s attack was the most lethal attack against the CIA in more than 25 years. Sami al-Oraydi, also from Jordan, was the al-Nusra Front in Syria’s former second-in-command and its religious authority, until he deemed the group incompatible with his viewpoints, and was arrested while trying to link up with more extreme elements.

As a result, Jordan has taken a stern line similar to that of Iraq when it comes to how it deals with militants and terrorists alike. Execution by hanging or extensive hard labour judgments, after having been awarded the right to a behind-closed-doors military tribunal, is the norm rather than the exception. It also appears that Jordan favours having mass executions, as it rarely executes people in the single digits.

As one of the Arab world’s more progressive states, it displays little in the way of gender bias either. For instance, in 2017, of the 120 people on death row, 10 per cent were women. Article 93 of the Jordanian Constitution specifies that “no death sentence may be carried out unless ratified by the King. Every such sentence shall be submitted to him by the Council of Ministers along with the council’s view on it.” On March 4th, 2017 Jordan carried out its largest mass execution to date. 15 men were executed, 10 of which had been sentenced for direct acts of terrorism.

The Changing of the Guard

“Jordan has to show the Arab world that there’s another way of doing things. We’re a monarchy, yes, but if we can show democracy that leads to a two-, three-, four-party system – left, right and centre – in a couple of years’ time, then the Muslim Brotherhood will no longer be something to contend with.”

– King Abdullah II of Jordan

The security situation that Jordan faces today is not unlike those conditions that the late King Hussein faced during the turbulent 1950s to 1970s. Having extensive first-hand experience, as well as having no small amount of foresight of what is to come, King Hussein saw it as vital that a small, nimble, and specialised military be prepared to fight in asymmetrical warfare within its borders. With this in mind, the Jordanian military is amongst the best in the region. King Hussein also opted to make sure that his son, Prince Abdullah, had strong military training and mindset.

In 1980, 18-year old Prince Abdullah was admitted to the Royal Military Academy Sandhurst and commissioned into the British Army as a Second Lieutenant. After completing his training, he served a year in Britain and West Germany as a Troop Commander in the 13th/18th Royal Hussars. After his British military service, he studied Middle Eastern Affairs at Pembroke College.

Upon returning home, he was immediately put into the Royal Jordanian Army, serving as an officer in the 40th Armored Brigade, and undergoing parachuting and freefall course overseen by the US Special Forces and the Central Intelligence Special Activities Directorate. In 1985, the Prince attended the Armored Officer’s Advanced Course at Fort Knox. By 1986, he became Commander of a tank company in the 91st Armored Brigade, holding the rank of Captain. He also served with the Royal Jordanian Air Force in its Anti-Tank Wing, where he was trained to fly attack helicopters.

Prince Abdullah completed a decade of military training programs in Jordan and the Western-allied countries forces, specialising in a variety of counter-insurgency tactics and strategic studies. This included special training with the British Army Special Air Services (SAS) and US Army Special Forces. Upon returning home, he assumed command of Jordan’s Special Forces and other elite units as a Brigadier General. He reorganised them into the Joint Special Operations Command, with an amalgam of the British and American Special Forces in mind.

Where his father, King Hussein, was known as a diplomat of world merit who would have given Machiavelli a run for his money, King Abdullah is regionally known as the “Warrior King.” Under King Abdullah’s leadership, the Jordanian military has become known as the most modern military in the Arab world.

With the King’s impeccable English (which was actually better than his Arabic when he first took to the throne, and sources say that he has since taken language lessons), Western schooling, and the image he presents, he is championed as the very definition of a moderate and pragmatic Arab leader by his Western benefactors.

King Abdullah is seen by the international community to be holding the Kingdom, and somewhat the region, together with spit and baling wire, much like Russian President Yeltsin after the demise of the Soviet Union.

If your plan is for one year plant rice. If your plan is for ten years plant trees. If your plan is for one hundred years educate children.

― Confucius

The Return of Hope and Dignity

Arguably, Amman, Jordan’s capital, is the business and educational centre of the Levant. Beirut, the capital of Lebanon, is its political centre, with Damascus, the capital of Syria, its cultural centre, and Baghdad, its historical centre. Yet, Jordan might well be a puppet state, an economic basket case, or both. Or it might, like Lebanon, be paralysed by communal fragmentation.

Since its creation 72 years ago, Jordan has had severe military, economic and communal crisis. Yet it has also been arguably one of the premier successful experiments, albeit not perfect, for what the Arab world might be. By regional standards, Jordan is an outstandingly forward-looking, efficiently governed, tolerant, and viable member of the international community, with a slowly emerging democratic foundation.

Amman, the city on the hills, is where over a third of Jordanians live. It is by regional standards a well designed, clean and maintained city. Its various enclaves mix the bustling old Arab neighbourhoods featuring souqs, small apartments and alley cats with that of dazzling modern neighbourhoods of stone villas, supermarkets and skyrises. Its main boulevards are lined with active construction sites of new high-rises, and are the home of international businesses and banks. The city also offers a wide array of amenities, such as excellent shops, luxury hotels, movie theatres, nightclubs and pleasant coffee houses and restaurants. The lifestyle in Amman is one that is mostly compatible with the Western expectation of what a capital, a metropolitan should be like.

Jordan seems to be, to an outside observer, moving in a different direction than the rest of the Arab world. Certainly, there are progressive, advantageous developments elsewhere. The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia appears to finally be, on uncertain legs, making some of the moves that it should have made decades ago, and override its ulama, i.e. religious leadership. Lebanon appears to finally be readying to recognise its destiny to unite its divided society and create an amalgam between the different realities found in Beirut, and in the countryside. While these hopeful changes are pleasing to see, they are far from anchored in their respective nations. A change in the winds could easily eradicate whatever progress has been made. In comparison, Jordan’s progressive movement is relatively well harmonised, and verifiably well anchored with its leadership.

With that having been said, Jordan remains, as most Middle Eastern countries are to one extent or another, a divided country. Life outside of the capital is significantly traditional, more conservative. However, unlike most other countries in the region, nearly every Jordanian has access to electricity and piped water, and one does not see signs of hunger. Literacy rates approach 95 per cent, and news consumption has remained steadfast in an era where the Western world’s rates have dropped like the proverbial stone. The press, though more restrained than in the West, is easily the freest in the Arab world.

“Jordan seeks to play only one role, that of a model state. It is our aim to set an example for our Arab brethren, not one that they need follow but one that will inspire them to seek a higher, happier destiny within their borders.”

– King Hussein of Jordan

In Jordan, more than 97 per cent of school-age children are enrolled in elementary and high schools. Jordan has also established more than fifty universities and more than a hundred community colleges, with nearly half of those students being women. Jordan has some of the best schools in the region, ranking number one in the Arab World in education, or 80 out of 188 in the Human Development Index. This despite the nation’s strained resources. The Jordanian Ministry of Education developed a highly advanced national curriculum, and many other nations in the region have improved their education system using Jordan as a model.

Despite this level of educational access, Jordanian youth have a hard time finding gainful employment. For instance, more than 70 per cent of the Jordanian population is under the age of 30. Much like all the other regional governments, Jordan’s government has largely failed in attempts at creating viable modern career paths for the increasingly well educated, but underutilised workforce. This means that the general unemployment rate in Jordan stands at 18 per cent, and among youth, it stands at 30 to 32 per cent depending on which source one cites.

While the notion that over 30 per cent of youth are unemployed, worse yet, it is widely believed that the shadow number of unemployed or non-gainful employed youth is even higher. Many well educated Jordanians are forced into taking menial jobs or underpaying jobs with little prospect for advancement.

“The Arab World is writing a new future; the pen is in our own hands.”

-King Abdullah II of Jordan

One could argue that access to some of the region’s best schools is, to an extent, a cause of the problems that Jordan is facing today. Schooling leads to having well-founded ambitions and being aware of opportunities. If the community then fails to meet the need for viable opportunities to match newfound ambitions and education levels, this will lead to an exodus, a brain drain, that will cause long-lasting damage to the society at large and the future of its hosting nation. And in Jordan, that is precisely what is happening. Jordanian youth are losing their hope and dignity. And with that – the Jordanian nation, perhaps even the region at large, is in danger. Indeed, for the troubled youth of the Levant, the future has seldom looked bleaker than it does today.

The West must not view this dire situation as simply an economic and humanitarian problem. It is, in fact, a growing geostrategic security threat. Not only are these conditions bound to create generations of frustrated denizens who may turn towards extremist fringe groups, but it will also lead to a loss in democratic ambition. Where there are no opportunities, totalitarianism finds firm ground. Such a drop in ambition will also lead to these emerging and fragile countries turning towards China and Russia, rather than the U.S.

At the end of the day, the future of the Levant rests on its youth. This is why the current trend must be reversed. Dignity and hope must be restored, and Jordan is the ideal place to begin that process.

John Sjoholm, Lima Charlie News

[Edited by Anthony A. LoPresti]

John Sjoholm is Lima Charlie’s Middle East Bureau Chief, Managing Editor, and founder of the consulting firm Erudite Group. A seasoned expert on Middle East and North Africa matters, he has a background in security contracting and has served as a geopolitical advisor to regional leaders. He was educated in religion and languages in Sana’a, Yemen, and Cairo, Egypt, and has lived in the region since 2005, contributing to numerous Western-supported stabilisation projects. He currently resides in Jordan. Follow John on Twitter @JohnSjoholmLC

Lima Charlie provides global news, featuring insight & analysis by military veterans and service members Worldwide.

For up-to-date news, please follow us on twitter at @LimaCharlieNews

In case you missed it:

![Image Welcome to Jordan! A Return of Hope and Dignity [Lima Charlie News]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/Welcome-to-Jordan.png)

![Image The Arabs - a "Manufactured" People? [Lima Charlie News]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/Arabs-A-Manufactured-People-Lima-Charlie-News-480x384.png)

![Image Welcome to Jordan! A Den of Spies and Fajitas for Dinner [Lima Charlie News]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/Welcome-to-Jordan-A-Den-of-Spies-and-Fajitas-for-Dinner-480x384.png)

![Image Welcome to Jordan! A buffer in a region of little stability, the Hashemite Kingdom faces enormous obstacles [Lima Charlie News][Photo: Salah Malkawi]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/Welcome-to-Jordan-480x384.png)

![Image The Arabs - a "Manufactured" People? [Lima Charlie News]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/Arabs-A-Manufactured-People-Lima-Charlie-News-150x100.png)

![Image Welcome to Jordan! A Den of Spies and Fajitas for Dinner [Lima Charlie News]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/Welcome-to-Jordan-A-Den-of-Spies-and-Fajitas-for-Dinner-150x100.png)