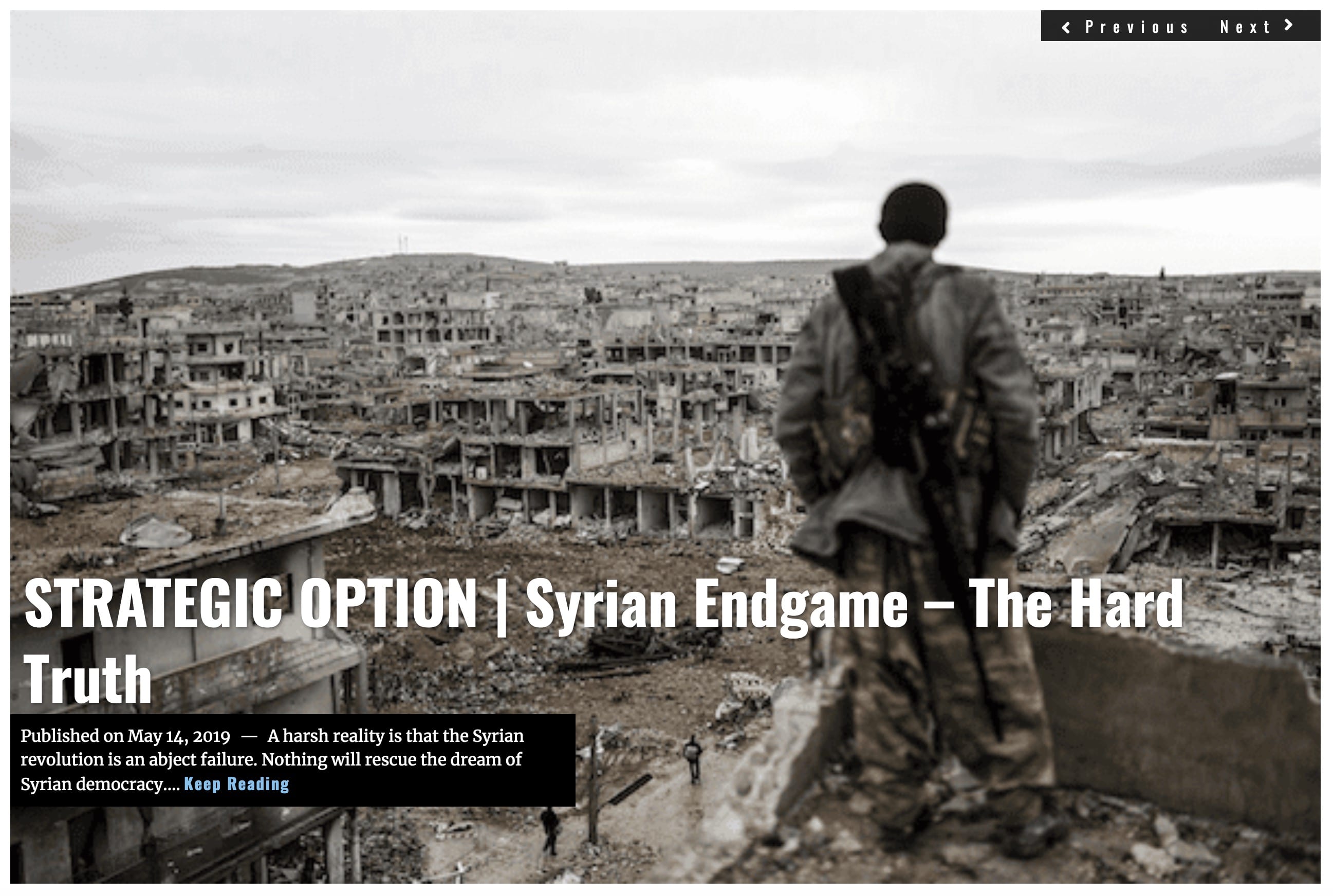

History’s superpowers have long employed military advisers around the world as extensions of a country’s power and influence. Russia has a wealth of experience when it comes to optimizing and maximizing the use of advisers. A prime example is the advisory operations of the former Soviet Union in Egypt.

I have long been particularly interested in the role of professional soldiers training foreign militaries of underdeveloped countries. I had two tours of duty in that capacity, in Egypt and Jordan. But I inherited my keen interest in what is generally referred to as security assistance from my father. As a professional Non-Commissioned Officer (NCO), my father served as an adviser to the Philippine Scouts prior to the second World War. In 1946, he was then deployed to Korea where he served in the Korean Military Advisory Group (KMAG) for 18 months. His many stories, as told to me, have well stood the test of time.

My father very much admired the Philippine Scouts, a force which fought as well as, or better than, the American units fighting against the Japanese in the battle for the Pacific. As he told their tale, he explained that these men did not need to be taught how to soldier. They were consummate professionals. Rather, my father’s contribution was technical assistance vis-a-vis signal communication. His experience during the war mirrored my own with the Jordanian forces in the 1970s. Back then, the Jordanian Army was a professional military, schooled by the British, yet it was in need of technical assistance. Today, the Jordanian military stands out as one of the best militaries in the Middle East, if not the best.

My father’s experience in Korea was far different. Korean soldiers were amongst the toughest in the world. I myself served with some in 1961-62 and saw firsthand the draconian punishment that the Korean command handed down towards recalcitrant troops. Yet, the American advisers in Korea during my father’s time, after having survived the horrors of the Second World War, held a reluctance in giving their all for a far away country that was mired in corruption and political fratricide. As my father related, the Korean soldier was inured to hardship and was a keen learner, but the officer corps was corrupt, incompetent and suffered from frequent turnover due to political infighting.

To some degree, this mirrors my experience in Egypt, 1981-1983. The Egyptian Army’s virtue was that it had soldiers inured to hardship, yet it consisted of a mostly self-indulgent officer corps. By and large, it had lost the fighting edge instilled in it by professional Egyptian officers and the hard-driving Soviet training mission to prepare for the Arab-Israeli War of 1973, more commonly referred to as the Yom Kippur War or Ramadan War. By the time I had arrived in Egypt in 1981, the general Egyptian way of soldiering was stuck in a bygone era of British colonial tradition, reminiscent of Winston Churchill’s classic “The River War: An Historical Account of the Reconquest of the Soudan” (1899). This entailed a slothful, materialistic minded officers corps, adhering to the adage that whoever sticks their neck out for anything gets it chopped off. The rule of the sage was to play it safe. I found the Egyptian Army to be demoralized and bereft of much-needed weaponry.

Yet, I knew even then that when Soviet and Warsaw Pact advisers had first arrived to Egypt in 1955, they found the Egyptian Army in even worse shape. While the Soviet training advisory mission was at first more of a political effort than military, after 1968 it had become a top military priority. It should be said, the Soviets did a remarkable job in rebuilding the Egyptian Army after its demoralizing defeat in the 1967 Six-Day War.

Despite their commendable service in Egypt, Soviet advisers were given very little recognition. The Russian military had long held the same lack of esteem for advisory jobs as the American army still does. It’s a simple fact, if your primary orientation in the military is in security assistance (i.e. advisory roles) you’ll have a hard time making flag officer. This was true for Russian officers in Egypt and Afghanistan, and it still holds true to this day.

This brings us to the purpose of this article.

While there are rooms full of books and materials about Russia’s involvement in the Middle East in terms of political, diplomatic, and arms assistance, there is very little about the efforts of the military adviser. Yet Russia, particularly, has a wealth of in-depth knowledge and experience when it comes to optimizing and maximizing the use of advisers in sensitive environments.

A prime example can be found in Russia’s extensive advisory operations in Egypt during the presidency of Gamal Abdel Nasser, prior to the expulsion of Russian military advisers from the country by President Anwar el‐Sadat beginning in 1972. The assistance Russia provided to Egypt in that era is similar in some respects to that given today to Syria’s Assad-led Damascus regime and its Syrian Arab Army (SAA).

![[Russian military adviser trains Syrians in mine clearance operations (Image: Russian Defence Ministry)]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/Russian-adviser-Syria-Russian-Defense-Ministry.jpg)

The Military Adviser – An Historic Role

The world’s superpowers have historically employed military and political advisers as extensions of influence and power, often to achieve long-term goals. For instance, America has kept advisers in the Philippines since the Taft administration.

One of the earliest American advisers in the Philippines was Captain John “Black Jack” Pershing, famed for his involvement in the hunt for Pancho Villa and later as a commander of American forces in World War I. Ultimately, his work leading indigenous Philippine troops during the Philippine-American War (1899-1902) in their unending battle against Islamic insurgents would earn him his Brigadier General-title.

Another famed military adviser was one of General Douglas MacArthur’s aides in Manila. Future president Dwight D. “Ike” Eisenhower, then a middle-aged U.S. Army Major, sought to define and organize the U.S.-supported Philippine national army in the mid-1930s. A Herculean task that few dared, it no doubt honed his skills, which would soon be tested during the D-Day invasion in Europe.

From Latin America to the depths of Asia’s jungles, America has dispatched military advisers throughout the world. Often these advisers have succeeded in accomplishing the impossible. And as warfare continues to move towards more asymmetrical micro-conflicts against non-state actors, the military and political adviser has grown in importance. This is an aspect that the U.S. government has thankfully realized.

The U.S. Army recently deployed the first Security Force Assistance Brigade (SFAB) out of Ft. Benning to Afghanistan in mid-2018. Its operation was a measurable success and upon its rotation completion, it was quickly decided that the 2nd SFAB would deploy to Afghanistan out of Ft. Bragg. The plan is to eventually create a six brigade force of soldiers specially trained to assist host countries to combine nation-building with assistance in military training of indigenous forces.

This is an innovation of some note, as the U.S. Army has seldom given much priority to the act of military assistance. This despite the fact that it’s one of the premier roles for the U.S. Army Special Forces, also known as the Green Berets, since the group’s inception in 1952.

The mission to train and assist is vague enough to allow virtually any type of training mission. Officially, the training program is modeled after the standard Infantry Combat brigade, leaving one to wonder what modifications and extensions could be made to encapsulate artillery, armor and other modern warfare tactics. At any rate, the most urgent issue for the SFABs will be the level and scope of the training they receive at the Military Training and Assistance Academy at Ft. Benning.

Will their training model include the cultural preparation needed? Will it require the seldom remembered but important study of lessons learned from other nations, not just the U.S.?

The Unrecognized and Unsung Role of Russia’s Egyptian Advisers

No one knew, or knows till now

About the awful heat and scorching sands

How in the fiery Arabian desert

We suffered thirst and yearning.

We defended the Fellah’s home and life

But no one ever thanked us

No one but Allah knew

How it was there and what happened.

And there in the sands on the Suez canal

It was as any war is:

Fate did not spare my comrades

But commanded me to remember them.

And to my last day, I’ll recall them

Whose life they gave for the struggle

Let the [Afghans], my friend and heir,

Sing about their fate and his.

-Vassily Murzintsev, “No One Knew”

The act of supporting Egypt was not a painless one for the Soviets. In a published poem entitled “No One Knew”, found in the excellent book “The Soviet-Israeli War 1967-1973” (by Isabella Ginor and Gideon Remez), Soviet veteran Vassily Murzintsev laments his time in Egypt. The poem captures the vital, yet usually unrecognized role of the so-called Security Assistance, more commonly known as an adviser, professional.

Russia’s military intervention in Egypt was a mammoth effort to rebuild the Egyptian army after its demoralizing defeat in the 1967 Six-Day War. Russia’s involvement with the Egyptian military was all encompassing and essential. The Soviets would become instrumental in Egypt regaining the honor of its military. General Saad Shazly, the Egyptian Army Chief of Staff at the time, wrote in his monograph “Crossing the Suez” that this accomplishment would have been impossible without the assistance of the Soviet advisers.

Can we learn from Russia’s experience in Egypt?

![[Soviet maps of the region in 1953 and 1967]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/Soviet-maps-1956-1967.png)

Cultural Clash: Russian Advisers and their Egyptian Hosts

In examining Russia’s experience in Egypt, many of the same problems the United States experienced in Vietnam, Iraq, Afghanistan, and even Iran prior to the revolution, were similarly experienced by Russian advisers. With around 20,000 Russians in Egypt, friction was bound to occur.

Soviet advisers were at every level involved in every aspect of Egyptian planning, training and logistics. Many senior advisers even brought their families and they lived in tightly guarded compounds where access in and out was rigidly controlled. At times the Russian commander in Egypt prohibited Russian families from leaving the compounds at all.

Once let out, the bumptiousness of Russians – from an Egyptian standpoint – was often on display. In one instance while traveling in Egypt in 1968, my wife and I took a small ferry across the Nile along with a number of Russian women and men. The women wore short house dresses with short-sleeved blouses. When we reached the other side of the Nile, the Egyptian boatman, his face twisted in disgust, kept repeating the word “zift” — a colloquialism that denotes anything dirty or lowly.

After some probing, the boatman said that his primary problem wasn’t so much their attire, but that the women had copious amounts of hair under their arms. To Egyptians, who prefer their women to have hair only on their heads, this was a massive breach of accepted behavior. To the ultra-conservative Muslim fellah this was more than a breach of etiquette, it was blasphemous. Understanding these norms is essential to intercultural relations.

Another cause for friction involved the apparent frugality of the Soviets. Russians in Egypt were paid relatively well, and were often granted monetary bonuses. Yet, when they left the compounds, often in groups, merchants complained they spent very little money, that they were cheap. Many Russians had volunteered for Egyptian duty in order to buy cars upon their return to Russia. At that time, this was beyond the dreams of most Soviet citizens. It was widely known that the monetary incentive was far more attractive than the patriotic duty of opposing capitalism.

![[President of Egypt Gamal Abdel Nasser greets First Secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union Nikita Khrushchev (L) during his visit to the United Arab Republic in 1964. (Photo Vasily Yegorov / ITAR-TASS)]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/Nikita-Khrushchev-Nasser-Egypt-1964-01.jpg)

General Saad Al Shazly probably expressed this tension best when he wrote:

“The Russians have many qualities, but concern for human feeling is not among them. They are brusque, harsh, frequently arrogant and unwilling to believe anyone has anything to teach them.”

Meanwhile, the Russians were highly critical of their Egyptian military hosts. Most irritating to Shazly was the condescending and preachy attitudes of Soviet officials. They often accused the Egyptians of failing to mobilize their people and seeking luxury instead of putting all their energies against Israel. They frequently asserted that the Egyptian army was largely composed of peasants, most of them poorly educated, and that officers were self-seeking, using their position for personal gain. The Russians also complained that the Egyptians did not know how to use Soviet weapons, and that the problem was low training standards of the Egyptians.

Despite some public acknowledgements of appreciation by the Egyptian embassy and Egyptian press, many sources, especially Israeli ones, described the eventual departure of Soviet advisers as a welcome relief to both Egyptians and Russians. Dan Asher in his book, “Egyptian Strategy for the Yom Kippur” wrote, “most Egyptian personnel loathed the Soviet’s self – righteous and heavy-handed involvement in all levels of the army.” A classmate of mine, Colonel Nicholas Krawciw, attached to a United Nations unit at the time, once recalled being invited to a party by Egyptian officers celebrating the departure of the Soviets.

The training of over 20,0000 Egyptians in Russia didn’t promote intercultural relations either, according to Colonel E.V. Badolato and the Egyptian writer, Mohammed Heikal. Social mixing between the Egyptians and Russians was almost non-existent. Nevertheless, in some aspects, the cultural hurdles were less for the Russians than Americans and other Western advisers.

![[Soviet military advisers against the background of the Pyramid of Khafre and the Great Sphinx, 1972]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/Screen-Shot-2019-06-03-at-1.47.02-PM.jpg)

Combat Training and a Tower of Babel

The Russian system was to instill in the trainee confidence and knowledge by using set-piece drills over and over. Generally speaking, trainees were never expected to exercise initiative or innovation but rather go through drills repeatedly until it was second nature. Basic soldier drills were emphasized, especially survival on the battlefield. If an Egyptian unit stopped for just a brief break, soldiers would immediately dig foxholes.

The Soviet training compared to Western training could be explained this way: in American training of small unit commanders the instructor would say, “This is the situation, as commander what are your actions?” In the Soviet system of training the instructor would say, “This is the situation, and this is what you should do. Now we will practice this until you get it right.”

Most of the training was “show and tell” in order to mitigate the language difficulties. Few Russians knew Arabic and fewer Egyptians knew Russian. The Cyrillic and Arabic writing systems are so difficult that translations were poorly done and often translations at general staff levels forced the Egyptians and Russians to use English.

The Russians also had immense problems with translators and interpreters qualified to work in the military field. In many cases, they were pulled out of language schools before they had completed their training creating a very disgruntled group. The translators were usually only half trained and were not at all happy being dumped in the desert when most were expecting some cushy foreign service posting.

There were often times when translators arrived without any tropical clothing or lodging arranged. Translator social media groups in the Glasnost period often complained about the shoddy treatment in Egypt at the hands of Soviet authorities. According to General Shazly, the Egyptians were often given no notice of the arrival of translators and had to produce clothing and living arrangements for the bewildered Soviet students in a matter of hours.

One of the facets of the Russian interface with Arabs, was that often Russians who spoke Arabic didn’t seem comfortable in their use of Arabic. Perhaps it was their fear of misspeaking creating a security breach. For instance, my counterpart, the Soviet assistant Army attaché in Jordan spoke modern standard Arabic quite well, but he continually asked the Jordanian officers if my Arabic was better than his. It was not, but the Jordanian officers would, just to “pull his chain” heap praise on my mixed Bedouin and Levantine Arabic. Like many KGB officers assigned to the Arab world, he had received two years of Arabic study. Yet the Arabic taught was of the modern standard variety, never used in normal Egyptian conversation.

Training the Trainers and Surviving Egypt

In both the Egyptian and Afghan interventions the Soviets had little time to train or acculturate their officers and troops. While staff work was excellent, it was largely modeled on Soviet intervention in Eastern bloc countries. As the dust settled it became clear that trainers had much to do to become competent at their jobs.

While advisers did do longer tours than American advisers in Iraq and Vietnam, usually about 18 months, and two years for senior officers, interpersonal skills were largely absent and they received no cultural training of any significance. The vast majority of officers knew nothing of Egypt and its people. What they were told was that Egypt, despite the so-called Nasser revolution, was still a “feudal state”.

While in Egypt the enemy was boredom and a lack of any diversions. Soviet troops, like most troops everywhere, were unimpressed with officially conducted tours of museums and historical tourist sites. Russian trainers worked hard and mostly learned on the job what they needed to know, but there was a lot of downtime. Examples include Ramadan, when training virtually shut down, and weeks of overwhelming heat which often limited training to a few hours a day.

Two major problems evident among the Russians in Afghanistan, vodka and drugs, were mostly absent in Egypt, but psychiatric problems were not. Junior officers and NCO’s found their spartan existence tough, and according to one of my fellow Egyptian instructors, a former Egyptian military psychiatrist, there were many cases of Russian soldiers and officers being sent home because of their inability to adjust to the environment.

Overall, the Russians were generally found to be dedicated instructors and stern masters. Despite the grumblings of senior Egyptian officers, President Nasser gave the Russian advisers carte blanche in training scenarios, all the while keeping a certain security distance between them. Nasser made it clear that the Russian instructors were the bosses and in time the Russians were even involved in promotions and assignments.

Russian advisers were intimately involved in the planning for the Ramadan War. Yet later, according to Yevgeny Primakov, former head of the Soviet Foreign Intelligence Service, President Sadat denied any Soviet involvement in the planning. As many sources attest, this is not true.

On an early official visit in 1978, with the U.S. Army Assistant Chief of Intelligence to Egypt, we were shown some of the minutely detailed and beautifully hand drawn cartographic depictions of the Suez Canal Israeli defensive positions and devices installed on the sand berms on the Israeli side. On many documents, in addition to Arabic text, I saw notes in Cyrillic. It should be added that the Russian skill in river crossing techniques was obvious in the Egyptian assault across the canal.

The Russian Equipment and Logistics System

The Russian logistics system and equipment tend to be better suited for third world recipients; for the most part, simpler to operate and maintain. The Russian “push” logistics system worked far better for the Egyptians than the U.S. “pull” system which depends on better educated and more mechanically inclined crewmen, as well as a systemic approach to logistics.

For instance, the common toolset, which, at that time was found in the American battalion maintenance, would be found at depot level in the Egyptian army. Egyptians were also incapable of battlefield recovery and getting damaged heavy weapons back into the battle. The Egyptian system, based on their level of training and education, was very single task oriented. For example, each tank crewman had specific jobs and the cross training required to do multiple tasks was not usually done.

The Russians reinforced their method of compartmentalized instruction. This seemingly inadequate training has to be understood within the context of the reality of the Egyptian educational level at the time and the general unfamiliarity with machinery. An example, the Egyptian army had to establish a driving school just to train drivers on the rudiments of driving wheeled vehicles.

Military logistics systems are culturally based. The Soviet/Russian system was predicated on a lesser degree of mechanical aptitude and education, which fitted into the Egyptian requirements and educational environment much better than the American systems. Many times in the interminable meetings with Egyptian officers I heard how much better American equipment was than its Russian counterpart, only to hear a few minutes later how “delicate” American equipment was compared to the Russian equipment.

No doubt this was true. For example, repair work on a tracked vehicle, which included pulling the engine out of the chassis, could be done at a U.S. battalion level. Yet, Egyptians did not have the expertise to use the required U.S. equipment (or perhaps the commanders did not want the responsibility). It had to be sent to the rear. In some cases, I felt this was simply a matter of certain officers maintaining their prerogatives and exercising the Arab military cultural tendency to hoard supplies and information.

Russian-Egyptian Cultural and Political Advantages

Despite the above, I do believe that at the time many similarities between Russian and Egyptian cultures existed. A general acceptance of authority, paranoia about military security, and living with few if any amenities are a few examples. The Egyptian soldier expected very little and received even less. Russian junior officers and NCO’s also had lower expectations.

The U.S. Department of Army Pamphlet, A Historical Study of Russian Combat Methods in WWII had described the Russian soldier as one who, “in addition to the simplicity which is revealed in his limited household needs and his primitive way of living, the Russian soldier has a close kinship with nature.” The forbearance of Russian advisers in Egypt suffering 120-degree temperatures, sleeping on the ground in cots just high enough to get them above the scorpions crawling around at night, were some of the privations endured by junior Soviet officers that bewildered Egyptian officers who themselves detested the desert.

Unless they were on exercises, most advisers retreated to their compounds in the evening, a policy acceptable to both the Egyptian and Russian security apparatuses. Personal relationships were abjured. In neither the Soviet army nor the Egyptian army were junior officers and NCO’s expected to exercise much initiative. In both militaries the NCO was simply a higher grade enlisted man and simply relayed and enforced orders. This made the training scenarios much easier for the Russians to conduct.

Renowned Sovietologist Walter Laqueur explained in his seminal studies of Russia in the Middle East that the Soviets came in with a relatively clean slate in regards to colonialism and attitude toward Israel. Western egregious political mistakes, such as the ill-fated Baghdad Pact, paved the way for Soviet involvement. Admiration among Arab intellectuals and military officers for the rapid Soviet industrialization and military prowess was also an important factor.

The large Muslim population of the USSR also enabled Russians to find enough compliant Muslims to present a “Muslim face” to the Arab World. Despite the earlier effort of the Stalinists to eradicate Islam in the USSR as incompatible with Marxism, according to American premier Middle East historian, Bernard Lewis, in consideration of geopolitical reasons, a great deal of intellectual outreach was expended to surface compatibility of Islam to communism.

https://youtu.be/7EVI8qvMGUM

[VIDEO: Russian advisers train Syrian troops – Zvezda]

Lessons Learned: A Look Forward

The Soviet experience in Egypt can be narrowed down to three salient lessons.

First, one cannot expect gratitude from even the most expensive and elaborate military assistance programs. Egyptian sources, other than Saad Shazly, scarcely mention the real impact of Russian assistance. Upon their departure, they also left behind a residue of ill-will.

Second, no long-term benefits accrued to the Russians. While Russia seems to be regenerating its relations with Egypt, both are very wary of political entanglements.

Third, and most importantly, the cultural component of the security assistance programs is vital. Despite the massive transfer of arms and equipment, along with the best professional efforts of competent Soviet officers, the constant friction between the two sides, especially at the top level, negated the Russian investment.

Some might say it has been quite a number of years since the last Soviet soldiers left Egypt, that times have changed. Yet it is well established that cultures change very slowly even as technologies surge ahead. The culture of societies, particularly the military subculture, changes almost imperceptibly and not always in a “progressive” sense.

An analysis of Russian military attempts to modernize and reform have been well captured in the book, “Military Reform and Militarism in Russia” by Aleksandr Golts. Attempts by a series of Russian Ministers of War, particularly Anatoliy Serdyukov, to institute reforms in the Russian armed forces were ultimately defeated by the colossal Russian military bureaucracy. As Golt wrote, “a Russian officer should stop being a minuscule cog in a huge military machine, deprived of the right to initiative, who acquires knowledge to the area relevant to him.”

Russia, under President Vladimir Putin, has apparently chosen a somewhat different path in Syria. Russia’s specialized forces, the Spetsnaz, have been engaged in combat alongside and sometimes commanding units of the pro-Assad regime forces. Rather than instituting the more formalized training that characterized the training of Egyptians and Afghans, it would seem that Russia has opted for a sort of on-the-job training offered by the ongoing conflict in Syria. Putin may not wish to face the issue of attriting young soldiers lives in another Afghanistan, an increasingly precious commodity in view of the rapidly declining Russian population. He has wisely chosen a sort of “hybrid warfare,” using irregular forces, mercenaries, clandestine methods, information and disinformation programs, at which the Russians have excelled for decades.

Professional military trainers require specialized education and personal attributes. Hopefully the American army creation of Security Force Assistance Brigades (SFAB) will develop the required attributes and knowledge. In establishing these units Americans have learned, somewhat belatedly, the unique requirements and roles of a military adviser. The SFAB should delve deeply into American Lessons learned, not just from Iraq or Afghanistan, but also from America’s training of Filipinos, Central American forces, Koreans, and irregular forces such as in the Burma Theater in World War II.

As important, while studying our own security assistance lessons learned, we should always ensure that we study those of other nations, particularly our rivals, and those of former enemies such as Nazi Germany and its training of European (non-German) Waffen SS units and the Muslim legions. In an article I wrote and published in 1999, I illustrated the failure of Western military advisers to institute lasting changes in the Arab military. Much of the failures can be attributed to futile attempts to re-create a military modeled on Western traditions and ethos.

History does not always repeat itself, and sometimes does in a modified and unrecognizable form. Charging ahead in a futurist fashion arrogantly assuming that technology and “new wave” doctrine will put us ahead of our adversaries is a recipe for disaster.

Colonel (Ret.) Norvell DeAtkine, for LIMA CHARLIE WORLD

[ Edited by John Sjoholm and Anthony A. LoPresti ]

U.S. Army Colonel (Ret.) Norvell DeAtkine spent nearly nine years of his 30-year military career in the Middle East as a military attache, student or political military officer. After retirement he taught for 18 years as the Middle East seminar director at the John F. Kennedy Special Warfare Center and School. Following his retirement from the JFK Center, Colonel DeAtkine held positions with the Defense Intelligence Agency, Iraqi Intelligence Cell and Marine Corps Cultural and Language Center. He has written a number of articles for various periodicals on primarily Middle Eastern military topics.

SOURCES:

The following sources are most helpful in terms of Soviet advisory material: Russia and the Arabs, by Yevgeny Primakov; Foxbats over Dimona and The Soviet-Israeli War 1967-1973, by Isabella Ginor and Gideon Remez; The Egyptian Army in Popular Culture, by Dakia Said Mostafa; The Yom Kippur War, by Abraham Rabinovich (the later version); The Soviet Union and Egypt 1945-1955, by Rami Ginat; The Soviet Union and the Yom Kippur War, by Galia Golan; Armies of Sand, by Kenneth Pollack; The Soviet Union and the Middle East, by Walter Laqueur; Naval War College Review, “A Clash of Cultures: The Expulsion of the Soviet Military Advisors from Egypt”, by E.V. Badolato. – Author

Lima Charlie World provides global news, featuring insight & analysis by military veterans, intelligence professionals and foreign policy experts Worldwide.

For up-to-date news, please follow us on twitter at @LimaCharlieNews

In case you missed it:

![The Art of Foreign Influence: The Russian Military Adviser [Lima Charlie News]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/The-Art-of-Foreign-Influence-The-Russian-Military-Adviser.png)

![Image Opinion | America’s Upside Down Foreign Policy [Lima Charlie News][Photo: Jonathan Ernst/Reuters]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/Opinion-America’s-Upside-Down-Foreign-Policy-480x384.jpg)

![Image Saudi Arabia, al Qaeda and the Salafist Dilemma - Part 3 of the American Foreign Policy Review series [Image: Lima Charlie News]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/Saudi-Arabia-al-Qaeda-and-the-Salafist-Dilemma-480x384.jpg)

![Image Opinion | America’s Upside Down Foreign Policy [Lima Charlie News][Photo: Jonathan Ernst/Reuters]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/Opinion-America’s-Upside-Down-Foreign-Policy-150x100.jpg)

![Image Saudi Arabia, al Qaeda and the Salafist Dilemma - Part 3 of the American Foreign Policy Review series [Image: Lima Charlie News]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/Saudi-Arabia-al-Qaeda-and-the-Salafist-Dilemma-150x100.jpg)

(Apologies in advance if this a duplicate post here, as unsure if my earlier original post arrived properly at LC News.)

————————-

Greetings to all in this thread.

** This detailed post by Norvell DeAtkine about Russian military advisers is a relevant, (robustly!!!) well-researched, and most-insightful article, including excellent coverage and the author’s examples about the Soviet military advisory presence in Egypt.

** The author’s observations and conclusions closely match and parallel findings and conclusions of much of my similar fieldwork research on the various “Groups of Soviet (later Russian) Military Technical Specialists” resident in several other countries in the Middle East (other than in Egypt), including their contrast and competition with corresponding Chinese [PRC variety] military technical assistance groups in Yemen.

** Must mention that the Russian military’s current presence and activities in Syria (as of June 2019) are profoundly more extensive, diversified, acknowledged, and overtly publicized than were their earlier episodes and deliberately low-profile activities in Egypt, Sudan, Libya, Iraq, Yemen, and Jordan (noticed during the late 1980s, when I was in that country).

Today is Wednesday, June 5, 2019.

Regards,

Stephen H. Franke

Lt Colonel, U.S. Army Retired

San Pedro, California

Greetings again to all in this thread.

Some additional comments which reinforce and illustrate some of the good points in this insightful and useful article.

[1] Reaction by Arab nationals in host countries to the overall ignorance, superficial preparation, and indifference displayed by Russian advisors toward appreciating and adapting their MO to suit the cultural sensitivities and patterns of their counterparts:

Egyptian contacts mentioned, during the several times I was there to support CENTCOM during BRIGHT STAR exercises and other training exchanges, that they usually referred to the Russian members of the earlier Soviet military advisory mission with the generic and sardonic label of “Ivan Pasha.” The HQ of that mission was based in Cairo.

** One Egyptian senior officer with a long memory clarified that that pejorative label emerged because of the Soviets’ preference and demand to house the families of the mission’s senior-level advisors in villas, clustered in the upscale residential quarter of Zamalek, which had previously been inhabited by senior-ranking British colonial officials.

[2] Poor use of drafted Russian university graduates with specialties in linguistics and the Arabic language:

CMT: The author’s comments are “spot on,” as verified by generally-consistent comments from several Russian contacts– now working as freelance professional translators and/or interpreters and living in major cities in Russia — who were similarly drafted after graduation to perform their two years of compulsory military service. ** After military induction and processing, they received little specialized training and related preparation to develop their skills in (ahem) “military Arabic” before they were selected for assignment and deployed to provide military interpreter support. They were assigned to the respective “Group of Soviet Military Technical Specialists” resident in various countries, including (inter alia), Egypt, Libya, Sudan, Yemen, Iraq, and Syria.

This article, IMPO, would be especially beneficial to our Army’s Security Force Assistance Command (SFAC HQ is based at Fort Bragg) and its assigned SFABs as a “read ahead and get smart early” reference should those SFABs be missioned and then plan and prepare to deploy for missions in countries in the CENTCOM AOR or AFRICOM AOR where the Soviets/Russians and/or other foreign military advisors/trainers, et al had been based and operated before in past years. Ditto suggestion in terms of relevant benefit to the Military Advisor Training Academy (MATA) at MCoE, Fort Benning.

(Have passed this article earlier to a U.S. Marine Corps unit I occasionally advise and assist in design and conduct of its country-specific pre-deployment training programs – aka PTPs – for possible use in preparing and certifying USMC-resourced “Security Assistance Teams” outbound to the CENTCOM AOR.)

Hope this helps. Today is Thursday, 27 June 2019.

Regards,

Stephen H. Franke

Lt Colonel, U.S. Army Retired

San Pedro, California

Yes! Finally someone writes about kafadan salla.