U.S. Army Colonel Norvell DeAtkine examines the age old clash between Arabs and Kurds.

The young Kurdish interpreter for American troops pointed to a tattered Iraqi flag flying over a small government building. He told me with bitterness in his voice that just seeing that flag made him feel humiliated.

In 2004, I was on a visit to an American Civil Affairs unit stationed near Suleimaniya and was able to observe first hand some of the remarkable qualities of the Kurds. Like many American soldiers, I was in awe of the fighting qualities of these people and their ability to not only survive, but also thrive, in one of the most hostile environments in the world.

The Kurds, a “people without a country” (as coined by French writer Gerard Chaliand), seemingly have every attribute necessary to establish their claim for independence. Mehrdad Izady, one of the foremost historians on Kurdistan, believes the Kurdish claims for nationhood are based “on a long common historical experience, their common world view, common national character, integrated economy, common national territory, and collective future aspirations.”

This summation is all the more remarkable because the Kurds, while having their own language, albeit in several dialects which can be as different as French from Italian, must read and write it in Arabic, Turkish, and Farsi in different scripts. As a tribal people, they are divided into hundreds of tribes and there exists a major fissure between urban and rural Kurds. Kurdologists also point out the significant cultural differences between the Kurds of the Erbil region and those of the Suleimaniya region.

The Kurds also have a long history of bitter internecine warfare. The internal conflicts are repetitive and tragic. Perhaps one incident sums up this tragedy best. When the “George Washington” of the Kurdish movement, Mulla Mustafa Barzani, died he was buried in the Kurdistan region of Iran. Later, Iranian Kurds, embittered by his memory dug up his grave and desecrated it.

Most observers would point to these divisions as the major reason the Kurds have not yet acquired an independent national state. Yet the most salient reason is that they remain landlocked, surrounded by neighbors who either claim they don’t exist, or have been trying to assimilate them. Turkish officers in my classes at Ft. Bragg, North Carolina, referred to the Kurds as “mountain Turks.” Using highly coercive measures, neighboring Arabs have tried to assimilate the Kurds for decades.

![Image Lunch with a Kurd warlord. [Author Col. Norvelle DeAtkine (left)]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/Kurd-Warlord-with-Col.-Norvelle-DeAtkine.jpg)

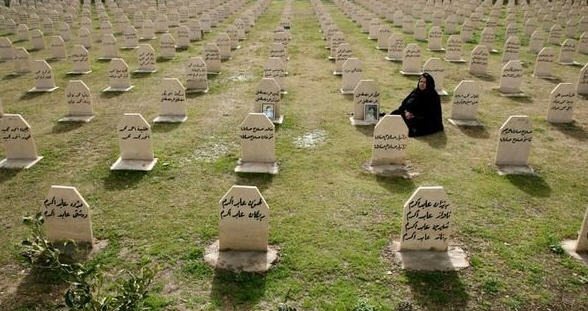

Of course, Saddam did not hesitate to use extermination operations, as with the Anfal operation, where an estimated 50,000 to 100,000 Kurds died at the hands of the Iraqi military and security forces. In this campaign, the Iraqis used weapons of mass destruction, most notoriously at the town of Halabjah, in which about 5,000 Kurds, mostly civilians, perished.

He told me with bitterness in his voice that just seeing that flag made him feel humiliated.

On the surface it would seem that the commonalities between Arab and Kurd would predict a more harmonious relationship. Both are originally tribal and primarily Sunni Muslim. Both are family-based cultures. Customs are similar, and in urban settings, there is a great deal of intermarriage.

Some observers, who seek to soft-pedal the acrimony between Kurd and Arab, point to the dysfunctional and rapacious leadership of both communities as the primary reason for the strife between them, and not any interpersonal rancor. They also point out the role of outside powers manipulating the Kurds. The United States and the West are usually singled out as the primary culprit, but in fact, Russia has played a very critical role. The Soviets were supplying arms to the Barzani Kurdish rebels, while at the same time Russian crews were flying the Tupolev T-16 bombing Kurdish rebels.

There is also no doubt that the Americans have, in Kurdish terms, betrayed the Kurds numerous times. This began with the failure to pursue President Woodrow Wilson’s Fourteen Points declaration, and the promises of a Kurdish state thereafter. Most recently, the U.S. failed to support the 2017 Kurdish Referendum for Independence. This resulted in a humiliating retreat by Kurdish forces.

The increase of Kurdish-Arab intermarriage, ironically, can be explained by the mass exodus of both Kurds and Arabs fleeing the violence of Baghdad to the relative safety of Kurdistan, ending up as refugees living in close proximity to another. Both Shi’a and Sunni militias and criminals targeted the close to half-million Kurds living in Baghdad. One source indicated over 300,000 departed Baghdad during the civil war.

One can hardly go wrong in impugning corrupt leadership in the Arab world for every ill that innervates the region. But these leaders know how to manipulate sectarian animosities that have been in place for a very long time.

Saddam Hussein, in his conferences with his inner circle, never uttered a disparaging word about Kurds or Shi’a (normally referred to as “people of the south” or “people of the north”). Yet his intelligence apparatus disseminated deprecating jokes about the Kurds. They were intended to portray Kurds with a slow mentality, perhaps comparable to a less politically correct time in the United States when Polish jokes were frequently heard. Another often heard rumor linked Kurdish antecedents to an ancient Jewish community. The Arab use of the derogatory term was all part of the powerful and often successful Ba’ath campaign to Arabize the Kurds. Many urban Kurds assimilated to simply make their lives more comfortable among their Arab neighbors and to secure better jobs in a state-run economy in which all employment and benefits flow from the top.

The Arabization program was both subtle and violently overt. It was often accomplished by simultaneous resettling of Kurds in Arab areas, scattering them to avoid too many in one region, and settling Arab families in Kurdish areas, moving them into former Kurdish homes. One of the more onerous missions of the Iraqi provisional government, after the liberation of Iraq, was the determination of who were the legitimate owners of homes in the Kirkuk area. Arab residents presented deeds issued by Saddam’s government, and the returning Kurds showed the authorities deeds dating back to the Ottoman era.

While arrests, executions, and forcible resettling of the Kurds was going on, the Ba’ath party was successful in recruiting a significant number of Kurds, especially women, ostensibly attracted by their superficial secular face. Meanwhile, Iraqi government officials toured Kurdistan, listening to hear grievances, and allowed the use of Kurdish in schools, along with various other simulations to assuage Kurdish sensitivities and probing naïve journalists. The sum and substance of the Iraqi government program was assimilation, willingly accepted or forcibly induced. Saddam used arts, literature and revisionist history for the task of eradicating the Kurdish culture.

The Ba’athi programs were clever and, combined with the climate of fear, obtained results that were at least partially successful. According to Denise Natali, who worked for twelve years in Kurdish regions of the Middle East, Saddam Hussein’s nomenclature used an ultra clever rewriting of history to promote a “Mesopotamian” identity over that of the non-Sunni Arab populations, then imperceptibly moved it toward an Arabized “Mesopotamian” version. The Saddam propaganda machine then implemented this program using Arab metaphors which “negated Kurds’ Median ancestry as an integral part of local Iraqi identity.” The pervasive and insidious effects of Ba’athist influence on the Iraqi population, Arab and Kurdish, is usually underestimated by the numerous “experts” who have emerged since the liberation lamenting the baleful effects of the “de-Ba’athification” program.

The Kurds in Arab Iraq suffered a great deal of discrimination, even before the war, but with the advent of the sectarian war, they became targets for both sides. The Sunni Arab Islamist terror groups considered them insufficiently Islamic and collaborators with the Western occupation forces. The Kurdish population, especially in the Suleimaiya region, has always been noted for a more liberal approach to the place of women in society. The “Islamic lite” social life of the Kurds has brought the wrath of Islamist groups such as Al Qaeda and the Islamic State.

In this regard, notes that I took during my visit to the Suleimaniyah region of Kurdistan are instructive in understanding the issues today.

The two primary fears of the educated elite with which I spoke were: (a) a deeply rooted fear of Arab nationalism which the Kurds believe is merely an extension of the Caliphate dream of Bin Laden, i.e., a twisted Islamism with a mystic belief in pan-Arabism; Kurds see Arab Nationalism as simply a hegemonic Sunni vehicle for power; and (b) a fear of Shia triumphalism in which the Shia gain control of Iraq and impose a draconian religious government on very unwilling Kurds.

Again and again, the Kurds, officials and others, voiced the belief that Islam acted as a retardant to progress and stability. They took pains to point out by way of old photographs, the lack of Islamic dress on females in the ’50s and early ’60s. The refrain often heard was that the Arabs imposed Islam on the Kurds. One Kurd told me that Suleimaniyah has more bars than Mosques. I do not believe this is true, but alcohol is certainly everywhere and easily obtainable.

![Image A liquor store in Suleimaniya, Iraqi Kurdistan [Photo: Col. Norvell DeAtkine]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/IZ-liquor-store-Kurdistan.jpg)

The ‘Islamic lite’ social life of the Kurds has brought the wrath of Islamist groups such as Al Qaeda and the Islamic State.

The Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS), containing large segments of the Saddam intelligence and special security forces, sought revenge for the Kurdish “betrayal” of Saddam’s forces in the Iran-Iraq war. The Shi’a, although they often referred to the Iran-Iraq war as “Saddam’s war,” were equally bitter about the Kurds acting as an arm of the Iranian military, keeping in mind that 80% of the Iraqi army rank and file were Shi’a and presumably at least 80% of the casualties were Shi’a.

Most writers on the Kurdish aspirations, e.g., Michael Gunter, Gerard Chaliand, Thomas Bois, and David McDowall, tend to be sympathetic to some degree. All of them recognize the immensity and complexity of bringing about a solution to the Kurdish issue. One writer, however, Edmund Ghareeb, a Lebanese–American professor, provides a scholarly presentation of the Arab view. He wrote in 1981, referring to the defeat of the Kurdish insurrection in 1975, “The demise of the Kurdish revolt, and the granting of limited autonomy to the Kurds in Iraq can be viewed as a victory for the Ba’ath Government and a step toward interregional accommodation and stability.” Ghareeb’s more tolerant view of the rapacious Saddam regime was a common one in the eighties, as his regime seemed to be a secular anecdote to the rise of fundamentalist Islam. As it turned out, the Iraqi government promises to the Kurds were worthless, something anticipated by the Kurds.

There is, however, another side of the Kurdish-Arab conflict.

Arabs will insist that the Kurds have been the betrayers as much as they have been betrayed. The Kurdish inclination has been to side with any force threatening the interests of the country in which they reside. This has defined them as a permanent fifth column in whatever country they reside. In Iraq, the Iraqi Kurds actively sided with the Iranians against their countrymen in a primordial struggle of Arab against Persian, creating a bitter taste among non-Kurdish Iraqis toward the Kurds to this day. Moreover, minorities within the Kurdish regions have not fared well, especially the Assyrian Christians. A great deal of persecution has been documented.

The Syria Kurds have in some ways a very different recent history than the Iraqi Kurds. They have, since the independence of Syria, been part of the “coalition of factions,” a tacit coalition of non-Sunni Arabs, who constitute 80% of the Syrian population. In their efforts to avoid Sunni domination, the Kurds, Druze, Christians and the Alawis have resisted either quietly or in armed insurrection. So for most of the history of the two Assad Alawi regimes, the Kurds have cooperated with the government. In fact, for a number of years, the Syrian government used their Kurds to augment the Turkish Kurd fight against the Turkish regime. The Turkish Kurd insurgent organization, Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK) greatly influenced the Syrian Kurdish formation of the Democratic Union Party (PYD) in 2003 and later the People’s Protection Unit (YPG), a militia which appears to have risen to its crescendo during the 2011 rebellion in Syria.

Mirroring the history of the Iraqi Kurds, political parties with a litany of names and ideologies have appeared, dissolved, and re-emerged, mostly with a strong strain of Marxist ideology. Like the Iraqi Kurds, despite their episodic cooperation with the Assad regime, they have been denied rights of basic citizenship, and often subjected to draconian measures of arrest, torture, and execution to keep them pacified. Because of the strong influence on the Syrian Kurds by the PKK, the Turks see them, especially the YPG, as virtually part of the PKK movement in Turkey.

What exactly is the conflict?

While some observers and pundits, principally Western, try to define the Kurdish-Arab conflict in terms of economic (oil) factors, outside regional and world power manipulation, and the ambitions of indigenous leaders, other analysts, particularly in the late ’50s and ’60s, saw it in terms of race and class.

In Iraq: the Search for National Identity, Liora Lukitz, writing about Kurdish opposition to integration within the Iraqi state, views all of the above factors, and others, as germane to the conflict. Yet Lukitz emphasizes that above all, the Kurdish-Arab conflict “was a cultural reaction from the Kurds, as a community with deep-rooted religious, cultural, and social characteristics.” “Culture,” notes Lukitz, embraces religion, traditions, symbols, and sets of beliefs “that mould the structure of a human group and determine the parameters of its members’ identities.”

In essence, the clash between Arabs and Kurds is a nativist and atavistic conflict in which the usual palliatives of political initiatives will not suffice.

Colonel (Ret.) Norvell DeAtkine, Lima Charlie News

[Edited by Anthony A. LoPresti]

U.S. Army Colonel (Ret.) Norvell DeAtkine spent nearly nine years of his 30-year military career in the Middle East as a military attache, student or political military officer. After retirement he taught for 18 years as the Middle East seminar director at the John F. Kennedy Special Warfare Center and School. Following his retirement from the JFK Center, Colonel DeAtkine held positions with the Defense Intelligence Agency, Iraqi Intelligence Cell and Marine Corps Cultural and Language Center. He has written a number of articles for various periodicals on primarily Middle Eastern military topics.

Lima Charlie provides global news, featuring insight & analysis by military veterans and intelligence professionals Worldwide.

For up-to-date news, please follow us on twitter at @LimaCharlieNews

In case you missed it:

![Image Arabs and Kurds - Why can’t they just get along? [Lima Charlie News]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/Arabs-and-Kurds-Why-can’t-they-just-get-along.png)

![STRATEGIC OPTION | Syrian Endgame - The Hard Truth [Lima Charlie News][Photo: Bulent Kilic]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/STRATEGIC-OPTION-Syrian-Endgame-e1558501175322-480x384.png)

![Image The Alevis Dilemma [Lima Charlie News]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/Alevis-Erdogan-480x384.png)

![STRATEGIC OPTION | Syrian Endgame - The Hard Truth [Lima Charlie News][Photo: Bulent Kilic]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/STRATEGIC-OPTION-Syrian-Endgame-e1558501175322-150x100.png)