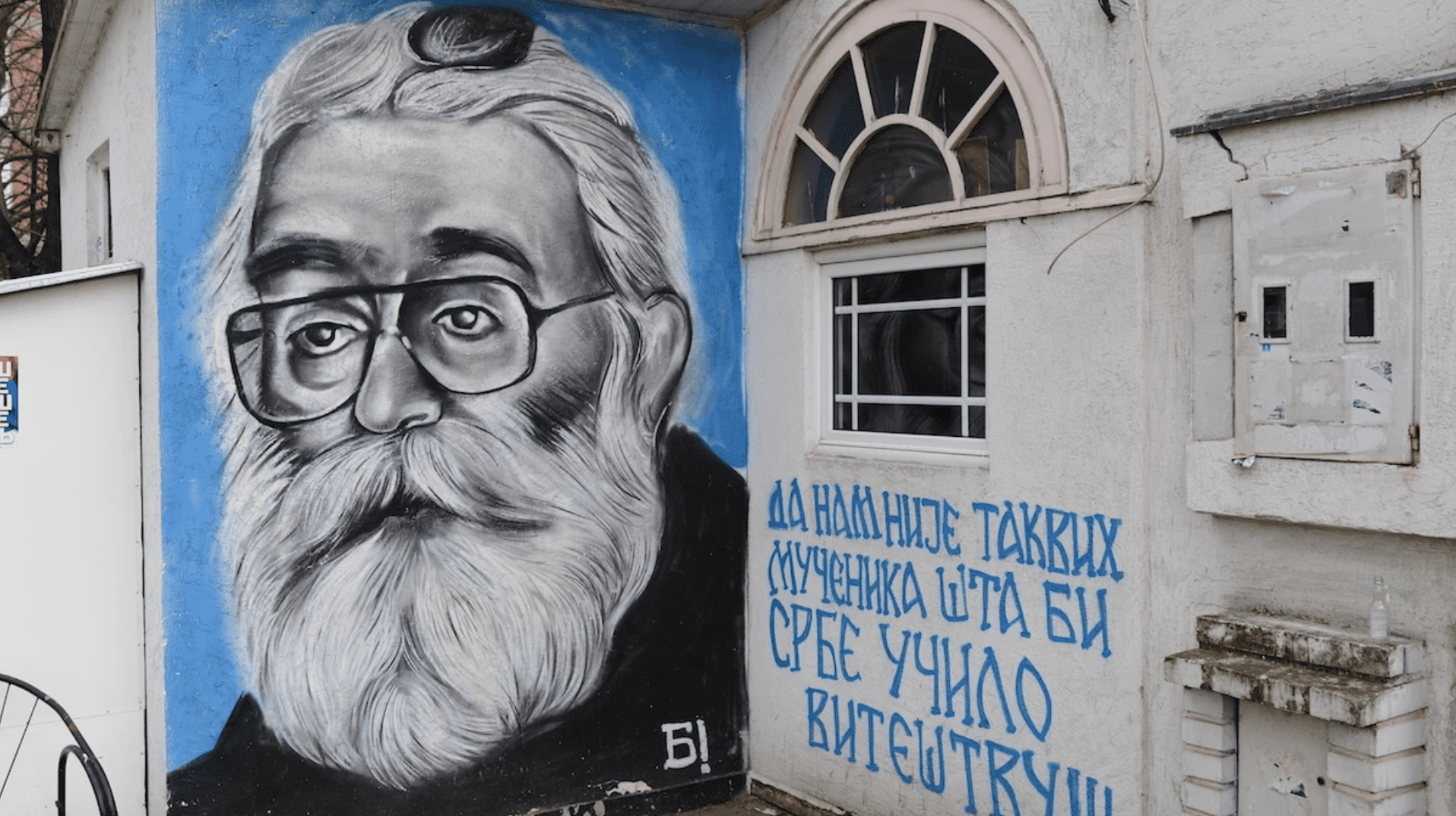

Amidst a bloody genocidal war that erupted after the breakup of Yugoslavia, in 1992, author William Stuebner was sent into the fray to represent the international community’s efforts to end the Bosnian War, Europe’s deadliest conflict since World War 2. In this, Stuebner would come to know Radovan Karadžić, the first president of Republika Srpska, the Bosnian Serb arm of the newly formed state of Bosnia and Herzegovina. Karadžić would serve as president during a brutal conflict fueled by ethnic cleansing that pit three main ethnic factions against each other, Muslim, Serbian and Croatian. With 100,000 dead and over 2.2 million people displaced, Karadžić would become a fugitive indicted for war crimes, evading arrest for over 10 years. On March 24, 2016, he was found guilty of genocide, war crimes, and crimes against humanity, which included the Srebrenica massacre and the siege of Sarajevo, and he was sentenced to 40 years imprisonment. Last month, on March 20, 2019, after an unsuccessful appeal Karadžić’s sentence was increased to life imprisonment. Serving as the Chief of Staff and Senior Deputy for Human Rights of the OSCE Mission to Bosnia and Herzegovina (1992 to 1995), Stuebner would have a front row seat to the political infighting, the banality of war and peace, and the international community’s incapability of handling the realities on the ground during the various conflicts that would become known as the Yugoslav Wars. – EDITORS

Over the past seven decades, I have had the occasion to meet all kinds of characters. I count among my acquaintances saints and sinners, heroes and cowards, pathological liars and paragons of integrity. The one trait they all had in common is that they are not defined by just one facet of their persona.

For example, Roberto D’Aubuisson (also known as Major Bob), famous for founding death squads in El Salvador and having had Archbishop Oscar Romero assassinated, passionately loved his country and his family and believed, in the end, that he would have to look God in the face and atone for his sins.

Radovan Karadžić, who on appeal has just had his sentence increased from forty years to life, is similarly complex and was driven by his personality and ego to reject the defense strategy that might have won him a vastly reduced sentence.

Karadžić requested that three Americans testify at his trial: Madeleine Albright; Richard Holbrooke; and me.

![Image [A member of the Serb nationalist militia known as the Tigers, led by Zeljko Raznatovic ("Arkan"), under the command of the Yugoslav People's Army (JNA) controlled by Serbian President Slobodan Milošević, kicks a Muslim woman (Ajsa Sabanovic, white sweater) who had been shot and killed by Serb forces during the Bijeljina massacre, April 1-2, 1992 (Photo: Ron Haviv)]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/war-in-bosnia-1992-ron-haviv.jpg)

The election fraud is in and of itself a very long story that revolved around the Administration insisting that the Bosnian election proceed, prematurely, by September 1996. This was done to signal to the American electorate that the promise of bringing home, after one year, 20,000 American troops sent to implement the Dayton Accords was being kept. For the Bosnians, this meant having to postpone locally scheduled elections, where it was believed there would be a high probability of widespread violence and voter intimidation.

Richard Holbrooke’s successor flew to Sarajevo to personally deliver the blunt message that the Bosnian election had to take place by sometime in September. Later, many Bosnians would joke that OSCE stood for “Organization to Secure Clinton’s Election.” Meanwhile anonymous Administration sources were quoted in the New York Times saying that I had resigned to hurt Bill Clinton’s reelection and to help his opponent, Bob Dole.

Having announced my resignation in Sarajevo, I drove to the city of Pale, then the Republika Srpska (RS) capital and Karadžić headquarters, with the Senior OSCE interpreter and my soon-to-be wife (an ethnic Serb who had absolutely no affinity for Karadžić’s regime and whose father had volunteered at the beginning of the war to join the Bosnian Army to defend Sarajevo). My intent was to formally inform Karadžić of my departure, and return to the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia (ICTY.)

We first met with Chief of Protocol Luka Petrovic to give him the bad news and the good news. I was leaving, and we were getting married. Before returning to Sarajevo to clean out my OSCE desk, I casually asked Luka if his “President” might like to speak with me, as I was a private citizen for one week before resuming my work with the ICTY.

Petrovic quickly placed a call to Karadžić who was chairing a cabinet meeting and announced his President would see me in five minutes. Leaving my fiancé behind, Luka and I climbed the stairs at the FAMOS (Fabrik Motora Sarajevo) aircraft parts factory where the President of the Srpska Republic had his wartime office.

Luka entered first and spoke for a few moments to Karadžić behind closed doors and then took his leave. Immediately, Karadžić came out to greet me and, sticking out his big paw to shake hands, said: “I understand you are going to marry a nice Serb girl!” Despite the fact that my wife rejected his cause and did not even identify herself as a Serb, in Karadžić’s mind with his warped worldview, if I was marrying a Serb, I must be pro-Serb.

![Image [Radovan Karadzic faces the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia (ICTY)(Photo: Valerie Kuypers)]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/2-Radovan-Karadzic-UN.jpg)

The Conversation

I had met Radovan Karadžić on previous occasions, and from the beginning had found him courteous and seemingly sincere. In fact, one needed to remind oneself of the enormity of the evil in which he was intimately involved so as not to find him likable. This was nothing like Serbian President Slobodan Milosevic, whom I used to describe as an unabashed pathological liar and fake, nor was it like Croatian President Franjo Tudjman, who was bullying and boorish.

This time, Karadžić’s demeanor was different. He seemed nervous and began speaking while pacing the room. Whenever a NATO helicopter passed over Pale like some modern-day Angel of Death, he would move to the window and peer out. After two nervous trips to the window, he practically shouted, “If NATO comes for me, there will be blood on the carpet!” I responded, “That is probably true, but let’s be serious. If NATO is determined to do something, there is no force on earth that can stop it, and the blood on the carpet will be yours.”

After this exchange, the mood shifted and we began to discuss the situation in earnest.

As stated previously, Karadžić knew me from our previous meetings and, I believe, saw me as honest and relatively unbiased. From our first encounter in Pale over two years earlier, I had pegged him as a romantic steeped in the Serb mythology I had learned about by reading Tim Juddah’s excellent book, The Serbs. Throughout my career, I have always read ahead to try to have some prior understanding of the history and customs of my interlocuters be they Ugandans, Salvadorans, Chechens or the peoples of the Former Yugoslavia.

Dr. Karadžić was a poet who played the traditional one-stringed Serbian gusle and recited epic poems from memory. Early on, someone had made him aware of a December 1992 night-time trek I had once taken into the surrounded enclave of Gorazde, which was besieged by the Bosnian Serb Army. Rather than condemning this as an unwarranted interference to assist his sworn enemies, Karadžić plied me with questions about what it was like traversing the icy mountains in mud and waist-deep snow in pitch darkness while dodging minefields and ambushes of his Army. He was especially enthralled by my stories of the Bosnian Muslims employing age-old smuggling routes and singing the old songs to take their minds off the cold and danger. I could almost feel him imagining himself on such a journey.

I believe he saw himself as the embodiment of a Serbian hero selflessly leading his people to the promised land. Of course, the fact that he grew up in Montenegro, where the epic poem “The Mountain Wreath” – a recount of the bloody battles against the Ottoman Turks – was required reading certainly helped to shape his worldview. He was a man for whom the Serbian defeat at Kosovo Polje (in 1389) was like current news.

During this meeting in May 1996, we did not have to retrace the historical terrain and we settled down to discuss Karadžić’s immediate problems. Over the course of the next hour, I learned that he was seriously interested in surrendering to NATO for transfer to The Hague where he could stand before the world and defend both himself and his people. By doing so, he believed he would eclipse Slobodan Milosevic in the pantheon of Serb heroes and take his rightful historical place alongside Prince Lazar of Serbia (medieval ruler over Serbia, 1373–1389 AC) who perished in battle against the Ottoman invaders. It was clear that Radovan preferred a jail cell to bleeding out on the floor of his office.

We talked about how we could affect a safe surrender that would preserve Karadžić’s reputation with his people but also enable NATO to accomplish his arrest without bloodshed and a remotely possible restart of hostilities. There was, however, a major roadblock that had nothing to do with NATO’s use of deadly force. It was that Radovan knew too much about the nature of the involvement of Milosevic and the Yugoslav Army General Command in Belgrade in war crimes and crimes against humanity. It seemed possible, even likely, that if he tried to turn himself in, one or more of his bodyguards, who had been secretly inserted by his Serbian enemies, would murder him and pin the blame on NATO.

![Image [Radovan Karadzic (R) and General Ratko Mladic, at Mt. Vlasic, April 1995 (Photo: RANKO CUKOVIC / REUTERS)]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/Radovan-Karadzic-005.jpg)

Once secured, Radovan would be helicoptered out to an American aircraft carrier in the Adriatic Sea where he would make a NATO-facilitated radio broadcast to every corner of Bosnia and Herzegovina stating that he had voluntarily surrendered and was on his way to the ICTY to defend the sacred honor of the Serbian people.

I, of course, had no authority to make any commitments, but we agreed that, once we had worked out all the details to Dr. Karadžić’s satisfaction, it would be my responsibility to sell the plan to my contacts in the Clinton Administration and NATO.

As our meeting drew to a close, Radovan asked if he and I could continue to meet to finalize the plan. I told him that when I returned to the employ of the ICTY, it would be awkward or even unethical for me to see him again, unless it was to accept his surrender. He then called for his personal advisor, Jovan Zametica, with whom I was quite well acquainted and who, at that time was not under indictment. We spoke for a few more minutes, and it was agreed that Jovan would be our intermediary going forward.

As I once explained to a Congressman, the Serbs and Croats both love the Muslims to death.

Follow-up with Jovan

Upon arriving back in Sarajevo, I immediately visited the American Embassy and the ICTY office to provide them with a detailed report on the Pale meeting. At that time, I still believed the Clinton Administration would welcome the opportunity to see a big fish like Karadžić safely in The Hague facing trial. I did not take into account how angry some officials were at me for my resignation, nor how fearful they were of any Serb reaction that might reveal the fragility of the peace initiated by the “brilliant diplomatic achievement” of the Dayton Agreement.

Little did I know that I was being viewed as a traitor whose actions could put Bill Clinton’s reelection in jeopardy. But, again, how that played out is another story.

Radovan’s personal advisor Jovan is an interesting character in his own right. He began life as Omer, son of one of President Alija Izetbegovic’s (the first president of the Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina) best friends and fellow Mladi Muslimani or Young Muslims. His mother was a Slovak. In other words, while he seemed to see himself as Super Serb, to the best of my knowledge he carries not one drop of Serbian blood: that is unless one accepts the Serb mythology that all Slavic Muslims are descended from Serbs who betrayed their Orthodox brethren by converting. Of course, then one would be denying Croatian mythology that claims they were Croats who betrayed their Catholic brethren.

Either way, as I once explained to a Congressman, the Serbs and Croats both love the Muslims to death.

Jovan had left Sarajevo with his mother after his parents divorced and ultimately ended up in the UK. There he became ‘John’ and eventually earned a Ph.D. at the London School of Economics. While there, he published a diatribe against Slobodan Milosevic accusing him of using and betraying Serbs for his own self-interest. He completed his metamorphosis in the summer of 1992 when he suddenly appeared in Pale as Jovan and an advisor to Radovan Karadžić.

I have often wondered whether Jovan suffered from an Oedipus Complex in that he became such a Serb nationalist in opposition to his father’s Muslim activism. Be that as it may, I never encountered anyone in the RS government who was more loyal to Karadžić. Once, when I visited Jovan at his quarters in a former Olympic hotel, I was surprised to find not only a Serbian Orthodox icon complete with a votive candle, but hanging next to it was a Messianic portrait of the Bosnian Serb President surrounded by admiring cherubs.

Through Jovan, I gained an insider’s view of the workings of the top civilian echelons of the RS government. It was clear that he felt slighted by the real Bosnian Serb civilian second-in-command, Momcilo Krajisnik, who refused to call him anything but Omer. Jovan also told me of how the brutish Krajisnik constantly humiliated the senior female political figure in the RS, Biljana Plavsic, commenting on her pre-war long-term relationship with a Muslim and even making crude remarks about her anatomy. It was not unusual for Momcilo to bring Biljana to tears in the middle of a cabinet meeting which may explain why she later turned and testified against some of her colleagues at the Hague Tribunal.

Radovan chose his intermediary well. Jovan is a very intelligent, business-like individual who was driven by his belief in Serb victimhood, loyalty to his boss and hatred of Karadžić’s enemies; especially Slobodan Milosevic.

Through Jovan, I felt I came to understand more about Karadžić’s aspirations and fears than I ever could have from the outside looking in. It became clear after a few weeks of meetings that his chief had a deep fear of possible Belgrade-sponsored infiltrators and that he was enamored with the idea of speaking on a world stage where he could use his oratory skills and charisma to become the greatest historical champion of Serbism, the last prophet so to speak. His idea, in Jovan’s words, was to mount an OJ Simpson-like defense.

Since at that time Karadžić believed NATO action was imminent, he planned to surprise everyone by going to The Hague and, at the trial, display his brilliance, prove his innocence and rescue his people from both international condemnation and Milosevic’s betrayal. Jovan so despised Milosevic that at a meeting in Belgrade in 1998, he told me, “Milosevic will end up like Ceausescu, but we’ll kill her (Milosevic’s wife who was one of the most reviled characters in the Former Yugoslavia) before we kill him.”

Nicolae Ceausescu had served as the General Secretary of the Soviet-supported Romanian Communist Party from 1965 until his death in 1989. His rule had not always been a popular one, and as the Soviet-supported rulers across eastern Europe fell one by one, Ceausescu quickly joined them. A quick but bloody rebellion against him saw to it. Along with his wife, Elena, they were both executed in the courthouse backyard after a brief trial held mere minutes earlier.

![Image [Slobodan Milosevic, then President of Serbia (L), with Radovan Karadzic (R)]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/Karadzic-Milosevic.jpeg)

Jovan was to lead the Bosnian Serb delegation to the Florence Conference on 13 June, where my former boss and friend Ambassador Bob Frowick, would announce whether or not the conditions existed for a fair and free election in Bosnia and Herzegovina. This was the issue over which I had resigned as Senior Deputy of the OSCE Mission. Bob, under extreme pressure from the Clinton Administration, and with his usual abundance of optimism that things would work out, announced the proper conditions did indeed exist, and the elections would take place in September of 1996.

A couple of days later, Jovan returned to Pale from Florence and called me over to have another meeting that I was sure would cement our surrender plan. Instead, he told me a tale that sickened me and destroyed what little faith I had left in Clinton Administration policies. He recounted a speech delivered by Judge Antonio Cassese, President of the ICTY, whom I knew to be a forthright and honest man with a passion for justice. Jovan said Cassese presented a tough, passionate appeal for UN member nations to affect the arrest of those indicted, including RS President Karadžić. Jovan joked, “Cassese made his case so well that I almost wanted to arrest Karadžić myself!”

However, he noticed that only the Bosnians and the Arab observers applauded Cassese, while the American delegation was visibly upset. Going over to speak to the Americans, he was greeted by an avalanche of colorful invective directed at the ICTY President. He then said to me, “I had to come back and tell my boss the Americans don’t want you, so why go sit in a cramped jail cell when no one is going to come for you?”

Unwilling to give up, I suggested to Jovan that we keep meeting, but I knew that what we had accomplished to date was no more than a wishful fantasy that was easily overturned by the Clinton Administration’s desire to continue the illusion of a stable Bosnia and Herzegovina to help their President’s reelection effort. A peaceful election had to take place in Bosnia by September 1996 (two months before the American election), to send the message to U.S. voters that all was well and that President Clinton’s promise to withdraw the 20,000 American peacekeepers after one year would be kept.

Shortly after the November Clinton reelection, the name of the peacekeeping force was changed from “Implementation Force” to “Stabilization Force.” Not one American soldier came home. That summer, Karadžić had already dropped out of sight.

![Image [Karadzic while in hiding, disguised with a beard, glasses and a top knot.]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/4-Karadzic-hiding.jpg)

Specifically, we needed help to secure our Srebrenica mass graves exhumations. NATO, especially the Americans, was fearful that too much open cooperation with Tribunal investigations could result in hostile acts against their soldiers. Consequentially, American soldiers, in whose sector we were operating, were only allowed to provide broad area security, and even that was only present when we had personnel on the grave sites. This left us vulnerable to snipers and acts of sabotage, like mining of the sites, which resulted in the significant extra expense of hiring people to sleep at the mass graves during hours of darkness when our careful forensics work could not be performed.

Through Zametica, I requested that RS police assist with close security and protection of convoys carrying remains as far as Bosnian Federation territory. I told Jovan this cooperation would reflect well on his boss should he ever be brought to trial. He agreed, and police personnel and vehicles arrived almost immediately.

Except for the police protection issue, I never gave Jovan any ideas that could have been useful to Karadžić’s defense strategy. Our long and frequent conversations, however, helped me to understand key points of the best case that could have been made but also why, given his deeper desires, Karadžić was unlikely to use them.

To my mind, Radovan Karadžić is undoubtedly guilty of illegal acts encompassing crimes of both omission and commission, but I am also convinced that had he been willing to use certain arguments, he might have received a much-reduced sentence. There might even have been a chance that if he survived into his 90s, he might once again have tasted freedom.

Cassese made his case so well that I almost wanted to arrest Karadžić myself!

– Jovan Zametica, personal advisor to Radovan Karadžić

The Case for Karadžić

Radovan Karadžić acted as his own trial attorney, but received legal advice from lawyers paid for by the ICTY. I met one of them, Peter Robinson, a couple of times, and he impressed me as professional and well-informed. The first time we met was after Karadžić had requested that three Americans testify at his trial: Madeleine Albright; Richard Holbrooke; and me.

It was obvious why he wanted the first two. He thought he could pin the charge of anti-Serb bias on the former Secretary of State and U.N. Ambassador who was key to the establishment of the ICTY and the release of satellite evidence of the Srebrenica massacre. Regarding Holbrooke, Karadžić had long claimed that if he dropped out of sight and did not cause problems for the peacekeeping mission, the former Assistant Secretary of State had promised in writing that he would never be prosecuted. Radovan was never able to produce a copy of the supposed letter signed by Holbrooke, so he wanted to make him testify under oath as to whether or not he had promised immunity from prosecution. This would probably have been seen as irrelevant by the judges, but Karadžić is no attorney.

But why call me, a relative nobody?

Probably part of the reason was that Karadžić knew I was unbiased, and because he hoped to have me testify to Serb victimhood. This stemmed from earlier conversations when he complained to me that there had been too many ICTY indictments against Serbs.

Victimhood is a valuable historical commodity. Every ethnic group in the Balkans tries to take the moral high ground by portraying themselves as the biggest victims. My response to Karadžić’s complaint was, “If 80% of crimes in the recent war were committed by persons who happened to be ethnic Serbs, then the indictments should reflect that fact. If, however, 5%, 10% or even up to 20% of victims were Serbs, the indictments should show that to be the case.”

![Image [Exhumation Site in Čančari valley (Photo Exhibit used in ICTY Srebrenica Cases, UN International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/Exhumation_Site_in_Čančari_valley.jpg)

Another, more mundane, reason for Karadžić calling me to testify may have been the result of an interview I had given earlier to Radio Free Europe in Prague. It was a wide-ranging interview that I was called upon to provide while my wife and I were on vacation there visiting friends. We departed the next day and never heard the translation of my answers. Once my wife obtained the long-forgotten interview, she discovered the translation had been horrendously flawed, and that my words were totally misconstrued making me sound almost like a rabid Serb apologist.

To Peter Robinson’s credit, it took him only a few minutes to realize there was no way he wanted me to appear in court.

Had I been directing Karadžić’s defense, I would have emphasized the following arguments:

(1) Karadžić had repeatedly used the RS Official Gazette during the war to remind his followers to obey international law. This, of course, could have been declared just a public relations ploy on the basis of ‘acts speak louder than words.’

(2) There were places of tranquility in the RS during the war where local police maintained civil order and refused to allow crimes of ethnic cleansing. A primary example of this was Prnjavor where the police commander, a member of Karadžić’s SDS political party ousted the paramilitaries and preserved the ethnic mixture of one of the most diverse municipalities in the country. Karadžić could have argued that where he had political control of the police atrocities did not happen. This could have been refuted by the fact that police in most areas were a large part of the problem, but he could have hoped the exceptions would prove the rule and would plant doubt in the minds of the judges. Another problem for Karadžić was that he had officially stated that no more than 2% of the population in the RS could be non-Serbs, thereby showing that he promoted ethnic cleansing.

(3) Given that the international and local media overwhelming filed negative (but mostly accurate) reports about the RS Army and Serb Paramilitary actions, he could have argued that he believed the media was biased against the Serbs, and so he believed them to be “fake news.” Many Serbs, for example, believed that reporting on the siege of Sarajevo was a made-up story and that the shelling and sniping was directed solely at the Bosnia Army that was assaulting Serb defensive positions. Once again, however, direct evidence and his own words could have been used against the RS President. In this case, Karadžić had foolishly appeared on Pale TV above Sarajevo with a Russian poet. Conveniently for the Court, the common language the two shared was English. Karadžić was shown looking down on scenes of carnage telling his fellow poet that he had written a poem years earlier about Sarajevo on fire and stating, “I was a real prophet.” This in and of itself was not so damning except that then Karadžić explained to the Russian how to use a heavy machine gun and then stood by while his friend shot at people on the streets below.

(4) Karadžić could have made the argument that many of the worst abuses were organized from Belgrade where Milosevic, the General Staff, and others committed crimes over which Karadžić had no control. In the Spring of 1995, Karadžić tried to relieve the top RS Army commander, Ratko Mladic of command under his authority as the President of the RS. Only one Serb General supported Karadžić while all the others backed Mladic as did, presumably, the Yugoslav Army General Staff in Belgrade which provided the bulk of logistical support to the RS Army including officers’ salaries. Karadžić could have argued that he did not control the military and paramilitaries but also that he had tried and failed. He, therefore, could not be held responsible for their crimes. The major weakness of this argument, once again, was that it could be shown that he did control the police who were complicit and he often bragged of his leadership of the Army.

(5) The final and most important argument would have been about Karadžić’s actions after the Srebrenica massacre of approximately 8,000 Bosniaks. Under the terms of the Dayton Agreement, no one indicted for war crimes and crimes against humanity could hold political office. Consequently, Karadžić was officially ousted from the Presidency. Later, my friend Bob Frowick, as Head of the OSCE Mission, also stripped him of his leadership of the SDS Party. In the interim, Karadžić had issued an order to the RS Ministry of Justice commanding that they investigate the Srebrenica killings and to pay particular attention to the possibility of extrajudicial executions. By the time the short investigative report was completed stating basically that ‘many Muslims had killed themselves, and the mass graves were used for sanitary purposes to dispose of battle casualties,’ it was too late. Karadžić’s argument could have been, ‘Look, once I became suspicious of the circumstances surrounding the deaths at Srebrenica, I took action as part of my legal responsibility to order an investigation. However, by the time the obviously flawed report came back, the OSCE had stripped me of the last vestiges of political authority, so there was nothing further I could do.’

While there are problems with all of these possible defense arguments, I believe a defense strategy built around them could have caused enough doubt in the minds of the judges that it would have convinced them that Karadžić bore the burden of far less command responsibility that the prosecution claimed. He would still, rightfully, have been convicted on serious charges, but it is a distinct possibility that his initial sentence could have been 20-25 years, rather than the initial 40 years and eventual life sentence he received upon appeal.

I believe the answer lies largely in his romanticism. Karadžić sees himself as a tragic heroic figure, not unlike Prince Lazar who it is said ‘Chose the Kingdom of Heaven’ (i.e. a martyr’s death in battle) rather than giving in and becoming a vassal of the Ottoman invader. In Serbian historiography, the greatest places of honor are reserved for martial characters.

Karadžić was a civilian leader, and even though he donned a camouflage uniform on occasion, his image was never that of a warrior. As a matter of fact, woodland print trousers on him looked like something Americans might describe as “mom jeans.” Combined with his unruly mop of hair, Karadžić did not cut much of a heroic figure. While he might eclipse an unpopular civilian like Milosevic, he would have far more difficulty supplanting someone like General Ratko Mladic.

By admitting he did not control the latter or directly guide the war effort, Karadžić would have appeared almost superfluous to the noble military struggle to defend the Serb people. Since he was pretty certain he would be convicted and given a long sentence no matter what he did, it is likely that he chose the honorable Serb path of martyrdom.

Why, then, did defendant Karadžić appeal his 40-year sentence and why is he now angrily disputing the life sentence handed down by the appeals panel?

It is all about remaining on the world stage and fighting for Serb honor and victimhood as long as possible. Croatian President Franjo Tudjman and Bosnian President Alija Izetbegovic both died before they were ever indicted for anything. Their stories will never be told by the ICTY. There will be no public judgment of their culpability. Milosevic also passed away before judgment was rendered, but he still spent years in court, and it was clear he would have been convicted. This means that only the top Serb leadership, and by extension the Serbian people, are seen as responsible for the recent horror.

As for the life sentence, the difference between that and a 40-year sentence for a man in his 70s is only symbolic, but symbolism is paramount in the Balkans. A life sentence basically says you are totally guilty and unredeemable. For Radovan Karadžić this is and always will be unacceptable.

![Image [Gravestones at the Potočari genocide memorial near Srebrenica (Michael Büker)]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/Srebrenica_massacre_memorial_gravestones_2009_1.jpg)

Karadžić sees himself as a tragic heroic figure.

![IMage [Testimony of witness Jela Ugarkovic on her account of Croatian Army attack on her village of Komic, August 5, 1995]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/Screen-Shot-2019-04-19-at-2.27.49-PM.jpg)

The Aftermath

Whatever comes out of the argument over the life sentence, and no matter how guilty Dr. Karadžić might be, the result will be largely negative for reconciliation in Bosnia and Herzegovina and the former Yugoslavia in general. For in that violent corner of the world, perceptions count more than reality. Perhaps the same is true everywhere.

The ICTY got a slow start on public outreach, and so the tale was told by Serb and Croat propagandists before the Court even got in the game. Overwhelmingly, Serbs and to a slightly lesser extent Croats, see the ICTY as a flawed international mechanism that picked sides from the very beginning.

Bosniaks, while somewhat disappointed by the overall achievements of the ICTY, will certainly be boosted by Karadžić’s conviction and sentence. But reconciliation cannot be successful if it is desired by only one of three antagonists. Serbs will go on thinking that “the others” started the war and that their own victims will be forgotten. They will believe that they have been further victimized by a biased, corrupt international judicial process. They will point to the fact that Tudjman and Izetbegovic escaped any blame whatsoever, something which in their collective minds will resonate forever.

Many Croatians, even though they initially may have supported the Court, were outraged when Croat generals were indicted. They will continue to see this as injustice even though they can claim some vindication from some of the convictions that have been overturned on appeal. The Croatian justice theory that has been promulgated for over twenty years is that they were fighting a defensive war and that, as such, the actions their leaders took could not be war crimes. The Croatian government has also been arguing that Bosnia and Herzegovina is a breeding ground contributing to the spread of Islamic extremism and that this supposed secret scheme of the Bosniak leadership resulted in their conflict with the Bosnian Army in 1993-1994.

Today, the nationalist politicians in Bosnia and Herzegovina and the rest of the Balkans are busily creating three or more (the Kosovars, Montenegrins, and Macedonians have their own) versions of truth and history. These conflicting tales of the origins of the war and who did what to whom are already sowing the seeds for the next round of vengeance. Just as the histories of the World Wars and the centuries-long Ottoman occupation fed this last war, the new histories will fuel the next.

To end on a slightly positive note, there is hope that the ICTY and other International Courts might still cause future mass murderers to take pause. While I am not optimistic, if this is the case, Radovan Karadžić’s “martyrdom” might yet serve some good purpose.

William Stuebner, for LIMA CHARLIE WORLD

[Edited by John Sjoholm and Anthony A. LoPresti]

[Subscribe to our newsletter for free and be the first to get Lima Charlie World updates delivered right to your inbox.]

William Stuebner served in the United States Army for twenty years, first in the Infantry and then as a military intelligence officer. The last five years of his career revolved around the wars in Central America where he first led a special intelligence team and then worked as the El Salvador desk officer for the Department of Defense. He was also an assistant professor in the Social Sciences Department of the United States Military Academy where he taught politics and political philosophy.

Stuebner’s Balkans work began in May 1992, shortly after the commencement of hostilities in Bosnia and Herzegovina and continues to this day. His assignments included: Humanitarian Assistance Officer for the Department of Defense; Bosnian Field Representative for the Office of Foreign Disaster Assistance, United States Agency for International Development; Expert on Mission, Office of the Prosecutor, International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia (twice); Senior Deputy Head of Mission for Human Rights and Chief of Staff, Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe Mission to Bosnia and Herzegovina. He has also headed two Non-Governmental Organizations dealing with international criminal justice and peace building.

Lima Charlie World provides global news, featuring insight & analysis by military veterans, intelligence professionals and foreign policy experts Worldwide.

For up-to-date news, please follow us on twitter at @LimaCharlieNews

In case you missed it:

![Image Murder, genocide, politics and the almost surrender of Radovan Karadžić [Lima Charlie News][Lima Charlie World]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/Radovan-Karadzic-001.png)

![Blossoming Russo-Turkish alliance leaves U.S., NATO behind [Lima Charlie News]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/Russia-Turkey-alliance-leaves-U.S.-NATO-behind-480x384.png)