OPINION | With the awakening belligerence of Putin’s Russia and China’s growing diplomatic and economic bluster, is Europe really prepared?

Si vis pacem, parabellum. If you want peace, prepare for war. This age-old adage formulated some 1,600 years ago by the famed Roman General Flavius Vegetius Renatus has not only withstood the winds of time, but its prescience has been continually reaffirmed by Western history.

The axiom’s meaning, that a strong defence is required to ensure lasting peace, is a simple but true insight that has been oft reflected upon since Flavius first uttered it. It has, however, represented yet another chasm between the mindset of military strategists, their political masters, the needs of the defender and the potential victim. In the civilian political world the axiom is frequently denounced as an excuse for needless aggression. Warmongering by frightful military leaders.

Yet, some from the political side of the aisle have wisely taken it to heart. Former Latvian president, Raimond Vejonis, once remarked in succinct fashion at a Swedish military conference, “nothing provokes Russia as much as weakness”.

Since the early 2000s, Russia has steadily increased its defence appropriations. Today its military budget amounts to approximately 4 per cent of Russia’s GDP. It is not the old, massive and often wasteful Soviet-era military service brigades that are being restored or upgraded. Instead, Russia is investing in high tech, new generation fighting machinery. Hypersonic cruisers, fifth-generation offensive air assets (including the Sukhoi Su-57 and the Tupolev Tu-22M3M planes) and new tanks are just some of the projects that will soon be incorporated into the national arsenal.

European countries have few answers to many of the measures Russia has taken in developing its military capabilities. Considering this, one can only wish that Flavius’ message might find a home in more of Europe’s politicians.

Russia is not alone on its path.

The People’s Republic of China (PRC) has apparent ambitions far beyond its immediate territorial area. For the time being China has not done anything analogous to Russia’s Crimean adventurism. Instead, it has been leveraging infrastructure projects to project power.

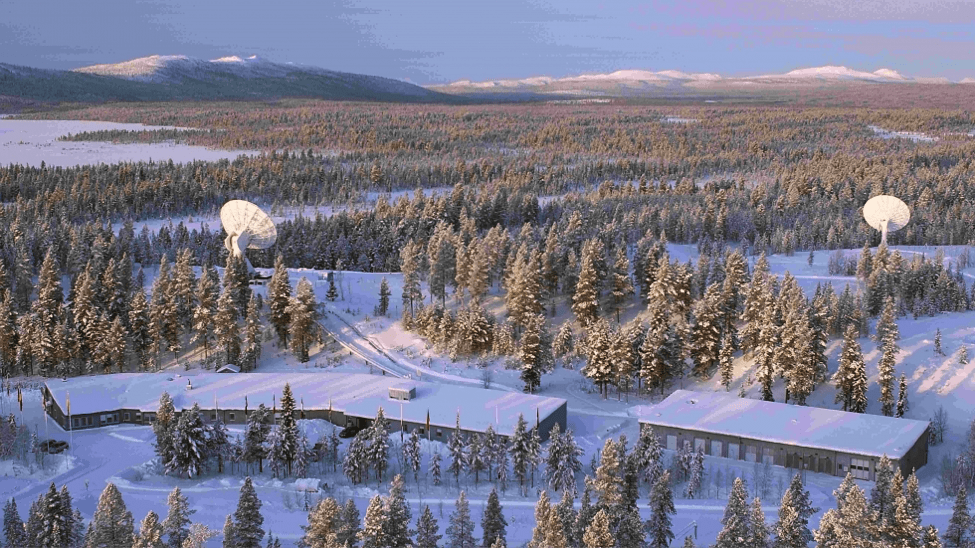

One example is the Chinese railway network that is growing westward through the purchase of important infrastructure nodes in gladly accepting European countries. For example, China’s direct rail link with Finland is being expanded to the rest of the baltic states. These infrastructure projects do not just give western politicians a financial incentive to be quiescent. They also open the door for the Chinese to potentially disrupt key technological and transit infrastructures – should they choose the stick over the carrot. In addition to this, China is showing increased interest in the northeastern passage in the Arctic.

The closeness of China’s defence apparatus with its private industry has been demonstrated by the state’s willingness to go to bat for the legally embattled tech giant Huawei Technologies.

[See Lima Charlie’s recent report: Huawei – China’s telecom giant hits a giant wall].

In addition to Huawei’s legal troubles, which focus on its alleged circumvention of Iranian sanctions, Huawei’s consumer products are suspected to be replete with backdoors which could be exploited for intelligence gathering, according to the heads of the FBI, the CIA, and the NSA.

There is no doubt that, as its economic interests abroad continue to grow, China will try to guard these interests. To an even greater extent than Russia, China has invested in both defence research and equipment. Perhaps the most obvious evidence of China’s ambition to become a global power is its domestic construction of aircraft carriers.

As the Russian threat continues to grow, either militarily or by an economic infiltration strategy similar to China, Russia might well end up on an overlapping and conflicting trajectory with China over Western matters.

One fact stands amid this backdrop – Europe has not done remotely enough to meet these growing threats.

However, in recent years, particularly in 2018, that has begun to change. Even Sweden’s perennially peacenik politicians have awoken to the emerging threats at their doorstep. This, after years of Swedish intelligence services loudly declaring, in as many venues as possible, that the Socialist Democrats (the premier party of Sweden) are being naive in regards to the nation’s defensive capabilities and the intent behind China’s infrastructure investments.

Si vis pacem, parabellum. If you want peace, prepare for war.

Yet despite this realisation, Sweden still does not hold membership in the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO). Sweden’s Defense Minister, Peter Hultqvist, has tried to compensate for this through a network of bi- and multilateral agreements with the U.S. as the centre of gravity. These agreements were largely supported by former U.S. Secretary of Defense (SecDef) James Mattis. With SecDef Mattis’ recent resignation, the transatlantic link has become less reliable, and now Sweden fears that it must actually pay the piper to gain the safety that it so direly needs. Despite its left-wing leadership, which has traditionally been against overt military coalitions, Sweden may soon be forced to join NATO in order to gain the much-needed advantages.

Regardless, Europe’s defence appropriations need to be raised. Since the end of the Cold War, many European NATO members have failed to meet the required military spending of 2 per cent of their GDP. In some cases, such as Belgium, they have never reached the spending requirement. This must change. It is high time to take Europe’s defence issue seriously.

The profession of defending Europe from outside foes must be made more attractive. Commanding higher salaries, more benefits and a well-functioning system for veterans are starters. These are things that European countries, with the possible exception of France, lack.

Inspiration can flow from the United States, where soldiers, for example, are given scholarships for post-graduate education. To facilitate this, the European Union (EU) could tap the European Defense Fund (EDF). The EDF is a €500 million per year fund managed by the EU to help coordinate and increase research and development in the defence market segment throughout the union. By 2021, the fund is set to have a budget by €13 billion. It could be made for implementing the necessary reforms.

It won’t be cheap to bring Europe up to the level. Equipping Europe will require appropriate technology investments. EDF intends to distribute EUR 1.5 billion per year after 2020 to various types of defence research and development. This is a good start, but the sum needs to be higher if the EU is to keep pace with developments in Russia and China. Targeted investments for the development of breakthrough technologies in cyber, A.I., electronic warfare, hypersonic weapons, etc., are needed.

It certainly won’t be easy. Prioritizing where the funds must go will be a challenge, especially in the less centralised and more-open European democratic landscape. For instance, what budgetary space should cyberspace and psychological warfare (PSYWAR) and defences receive? After the latest U.S. presidential election and the BREXIT campaign, both having suffered from suspected Russian influence, this is a threat that the EU must spend significant resources in combating. If Russian involvement altered either decision, it managed to create deep gaps in the Western alliance without firing a single shot. This must not happen again.

After all, if the EU is to stand against Russia, it must do everything possible to stop Russian or Chinese interference in its political scene, as well as prevent espionage against its industries. Europe’s economic and cultural capital is a glittering prize, and unless Europe is protected by a prickly multi-layered defence apparatus, it will prove an irresistible political adventure for outside interests.

In other words, if we want a lasting peace, we must also prepare for the opposite.

[Main Photo (filtered): Joakim Elovsson]

John Sjoholm, Lima Charlie News

John Sjoholm is Lima Charlie’s Middle East Bureau Chief, Managing Editor, and founder of the consulting firm Erudite Group. A seasoned expert on Middle East and North Africa matters, he has a background in security contracting and has served as a geopolitical advisor to regional leaders. He was educated in religion and languages in Sana’a, Yemen, and Cairo, Egypt, and has lived in the region since 2005, contributing to numerous Western-supported stabilisation projects. He currently resides in Jordan. Follow John on Twitter @JohnSjoholmLC

Lima Charlie provides global news, featuring insight & analysis by military veterans and intelligence professionals Worldwide.

For up-to-date news, please follow us on twitter at @LimaCharlieNews

In case you missed it:

![image Workers Unite! Cold War Chronicles and Reflections on the Prague Spring, Part 2 [Lima Charlie News]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/Workers-Unite-Cold-War-Chronicles-and-Reflections-on-the-Prague-Spring-Part-2-480x384.png)

![Blossoming Russo-Turkish alliance leaves U.S., NATO behind [Lima Charlie News]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/Russia-Turkey-alliance-leaves-U.S.-NATO-behind-480x384.png)

![Image Russia and China’s 'hybrid warfare' - Does the West even care? [Lima Charlie News]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/Russia-China-Hybrid-Warfare-02-480x384.png)

![Image Murder, genocide, politics and the almost surrender of Radovan Karadžić [Lima Charlie News][Lima Charlie World]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/Radovan-Karadzic-001-480x384.png)

![Image The Alevis Dilemma [Lima Charlie News]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/Alevis-Erdogan-480x384.png)

![image Workers Unite! Cold War Chronicles and Reflections on the Prague Spring, Part 2 [Lima Charlie News]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/Workers-Unite-Cold-War-Chronicles-and-Reflections-on-the-Prague-Spring-Part-2-150x100.png)