Last week January’s jobs report sent markets into a spiral. This week all eyes are on January’s Consumer Price Index on Wednesday and on Thursday’s Producer Price Index. These reports give investors the latest data, and, with a .5% increase in consumer prices in January, are confirming last week’s fears of inflation.

U.S. stocks have been on a hot streak for more than a year. At first, the Dow Jones Industrial Average was at 20,000 points. Soon after that, it was at 21,000. Then 22, 23, 24 … Overall, the DJIA rose 25 percent in 2017.

Last week served as a wake up call, as tumbles on Monday and Thursday redemonstrated that markets are still a rollercoaster. The tumble, according to strategists, has been dubbed a “correction,” or when a stock market falls at least 10 percent from a recent high.

Experts are pointing to the Department of Labor’s January jobs report as the spark for the upset among investors. According to the release, the American economy added 200,000 jobs in January, which is the fastest rate of growth since 2009. Although good news for workers, markets interpreted it as the beginning a long-anticipated spike in inflation.

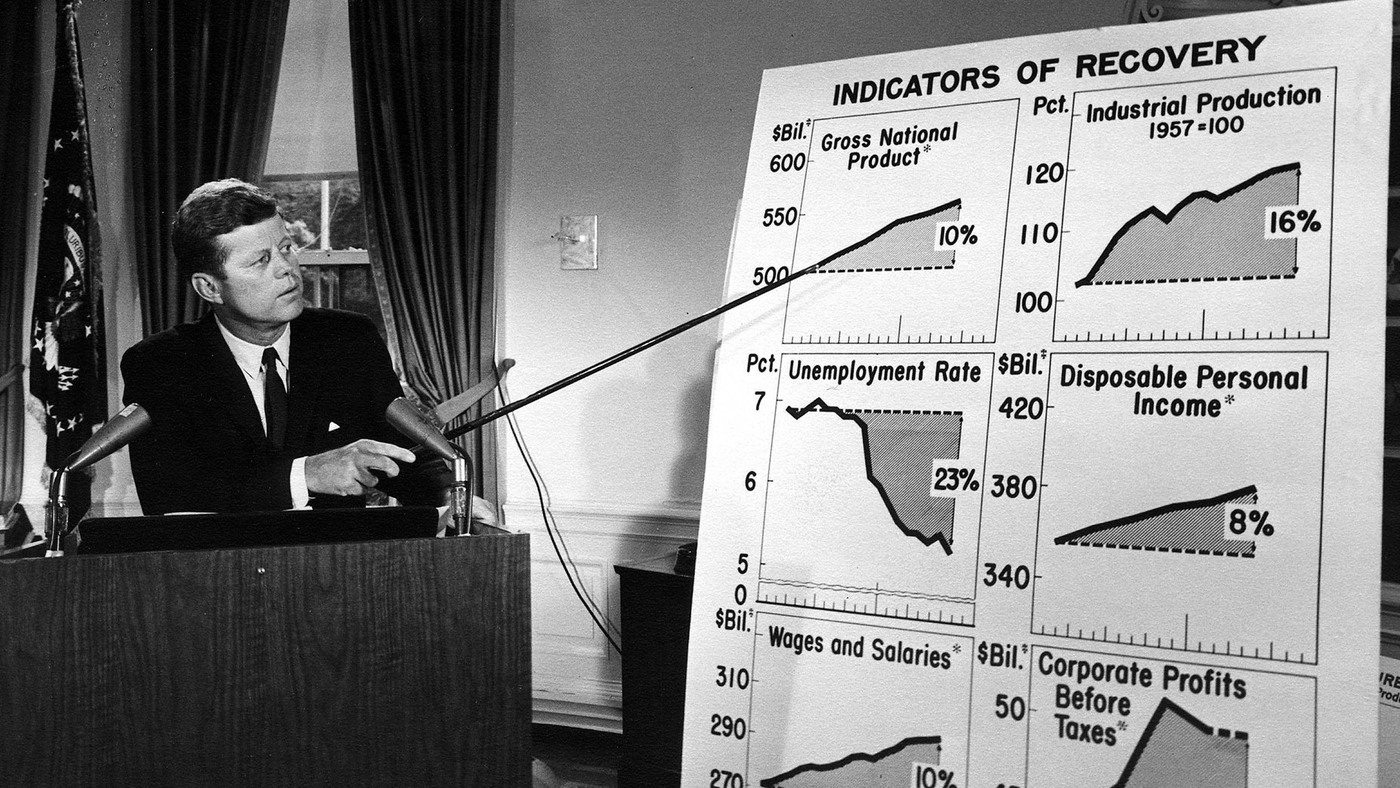

This fear of inflation is partially fueled by memories of the factors that led to an increase in inflation in the late 1960s. First, in 1964, tax cuts implemented by President John F. Kennedy came into effect. Then spending exploded in order to pay for the Vietnam War and President Lyndon B. Johnson’s “Great Society” programs. Finally, as unemployment fell, the federal budget deficit began to climb, and, as more cash flowed into the economy, inflation jumped from 3 to 5 percent between 1968 and 1969.

Now, in 2018, as the labor market booms and tax cuts are set to double the federal deficit to $1 trillion (5% of GDP), the specter of inflation has returned as history appears to be repeating itself. This all comes alongside a budget deal that was signed on Feb. 9, which will increase spending caps by $300 billion, and is expected to pump more money into the U.S. economy than at any point since 1945, aside from the immediate aftermath of the 2008 and 1980s financial crises. And this week, the price index reports will show if this activity is generating a jump in prices.

Fears of Politicization of Central Banks

There is yet another factor contributing to uncertainty, which is the new leadership of the central banking system of the United States. Jerome Powell took office as Chair of the Federal Reserve, replacing Janet Yellen, on Feb. 5th. Mr. Powell’s likely policy decisions are somewhat murky. Unlike his immediate predecessors Mrs. Yellen, Mr. Ben Bernanke, and Mr. Alan Greenspan, Jerome Powell isn’t a PhD economist, but a lawyer who worked his way up at the Carlyle Group. President Trump’s one other appointee to the Federal Reserve board was also a Carlyle Group alumnus.

Personnel turnover will occur amongst many foreign central banks in the near-future, as well. The head of the People’s Bank of China, Zhou Xiaochuan, is likely to step down in the coming weeks. Four of the six seats on the board of the European Central Bank (ECB) can be replaced over the next 2 years; Spain’s Economy Minister Luis de Guindos is likely to fill the open post of the Vice Presidency of the ECB. The head of the Bank of Japan was re-appointed on Friday; to continue a program of weakening the yen.

In previous years, the appointment of leadership to central banks did not garner much political interest. In the United States, multiple administrations renewed Alan Greenspan’s service as Fed Chair for 19 years. Similarly in China, Mr. Zhou will have served for 15 years before retiring. However, since the 2007 financial crisis, with legislatures in a state of deadlock, central banks have been the primary instrument of economic policy. This has caught politicians’ interest, and Powell’s initial appointment as a Republican to the Fed in 2011 was an olive branch to Republicans who had filibustered a previous appointment.

And politicians exerting pressure on central banks can be bad news for inflation. Faced with growing inflation in the lead up to the 1972 Presidential Election, President Richard Nixon fired the sitting chair of the Federal Reserve and pressured the replacement to keep money flowing into the economy, because (in Nixon’s words) “we’ll take inflation if necessary, but we can’t take unemployment.”

[Title photo: Reuters]

LIMA CHARLIE NEWS, with Diego Lynch

Lima Charlie provides global news, insight & analysis by military veterans and service members Worldwide.

For up-to-date news, please follow us on twitter at @LimaCharlieNews

![Image U.S. markets prepare for inflation and politicized central banks [Image Reuters]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/us-market.jpg)

![Image Fed announcement triggers best trading session in over eight months [Lima Charlie News]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/Jerome-Powell-Reuters-480x384.jpg)

![Image Drop in oil prices may trigger unintended consequences [Lima Charlie News]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/main_900-480x384.jpg)

![Image This Week in Business Intelligence [Lima Charlie News]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/This-Week-in-Business-Intelligence-Lima-Charlie-Business-Intel-Report-480x384.png)

![Image Memorial Day may soon be a remembrance of democracy and those who had the courage to defend it [Lima Charlie News]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/Memorial-Day-may-soon-be-a-remembrance-of-democracy-and-those-who-had-the-courage-to-defend-it-Lima-Charlie-News-480x384.png)

![The Mind of Bolton - AUMF and the New Iran War [Lima Charlie News]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/Inside-the-mind-of-Bolton-Lima-Charlie-News-main-01-480x384.png)

![Image Fed announcement triggers best trading session in over eight months [Lima Charlie News]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/Jerome-Powell-Reuters-150x100.jpg)

![Image Drop in oil prices may trigger unintended consequences [Lima Charlie News]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/main_900-150x100.jpg)