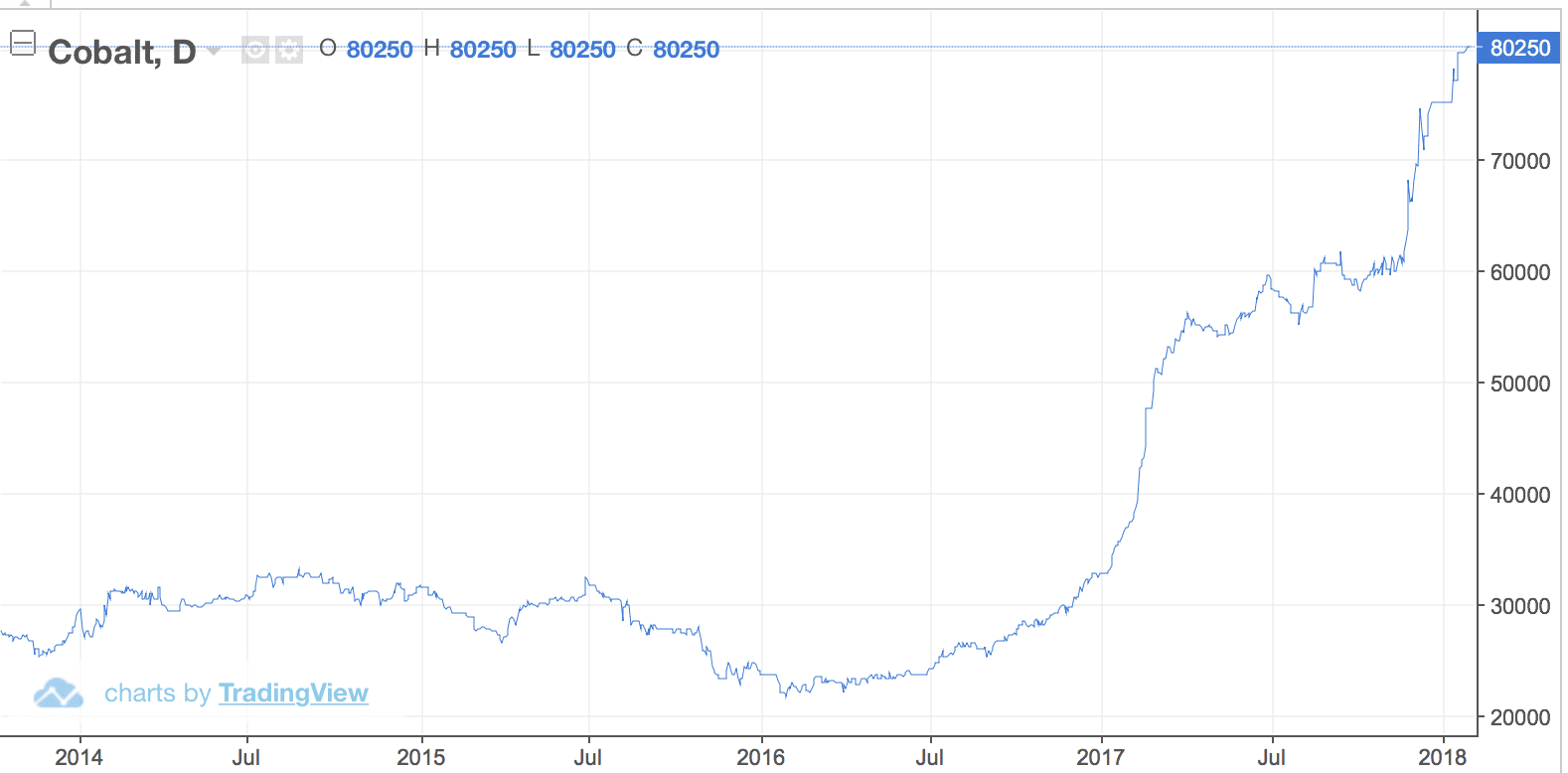

The Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) is attempting to increase revenue from the 270% surge in cobalt prices in the last year by raising taxes on the metal five-fold. Foreign governments and corporations who benefit from lower cobalt prices have protested the tax hike. Congo holds half the world’s cobalt reserves, a key component of the rechargeable lithium-ion batteries that power iPhones and electric cars.

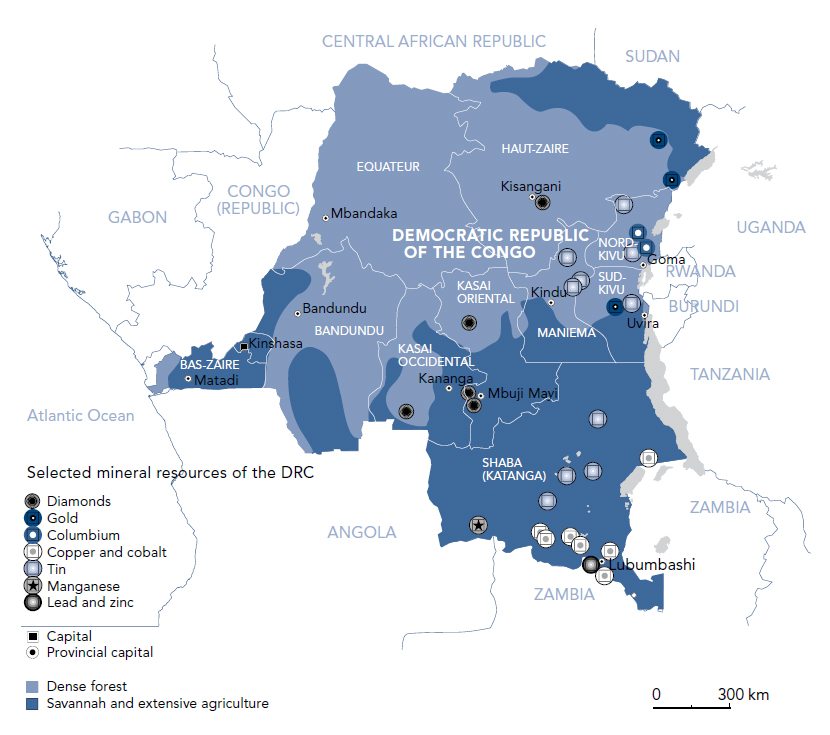

The lion’s share of cobalt in the DRC is the South Eastern Katanga province, which was relatively free of the perennial violence which has plagued the mining regions in North and South Kivu. However, since rebels launched an attack on the regional capital in 2013, violence in the region picked up. Fighting between the government and “Mai-mai” rebels has displaced a quarter million people from Lualaba, the area in Katanga with the largest mines, since July 2016.

Amnesty International is lobbying to have cobalt added to the “3TGs,” officially designated conflict minerals that are subject to additional regulatory scrutiny. Amnesty International publicly shames companies, alleging that the majority of major users of cobalt turn a blind eye to the use of child labor in its production. Blockchain technology has recently been proposed to track cobalt from mines in DRC to products as a way of ensuring it has not been mined by children.

Consumers of lithium-powered electronics and hybrid cars may be unaware. However, for technology firms that require cobalt to capitalize on increased demand for batteries and electric cars, such as Tesla, this is bad news. The new proposed tax rate will also be bad for countries like China, which dominates cobalt refining and accounts for 80% of global cobalt chemicals output.

The DRC’s tax proposal is also expected to drive up the price of cobalt further, which is typically found alongside copper, in an already tightening market. Metal prices have recently been in flux, especially in the last week, as zinc, nickel, copper and lead all have hit multi-year highs in the last month.

In order to become official law, the tax legislation, which also includes wide ranging and costly changes to the metal extraction industry, needs the signature of the DRC President Joseph Kabila.

Foreign executives and diplomats hope to encourage President Kabila not to sign it. CEOs from Glencore, a Swiss commodities group, and Randgold Resources, a UK-listed gold miner, have both traveled to the DRC to oppose the new law. Last month, those two companies, along with China Molybdenum, signed a letter promising to oppose the legislation “by all domestic and international means at their disposal.”

“One can expect unprecedented lobbying efforts from the sector to change the president’s mind before he signs the revised mining code into law,” Elisabeth Caesens of Resource Matters, a Brussels-based non-government organization, told the Financial Times.

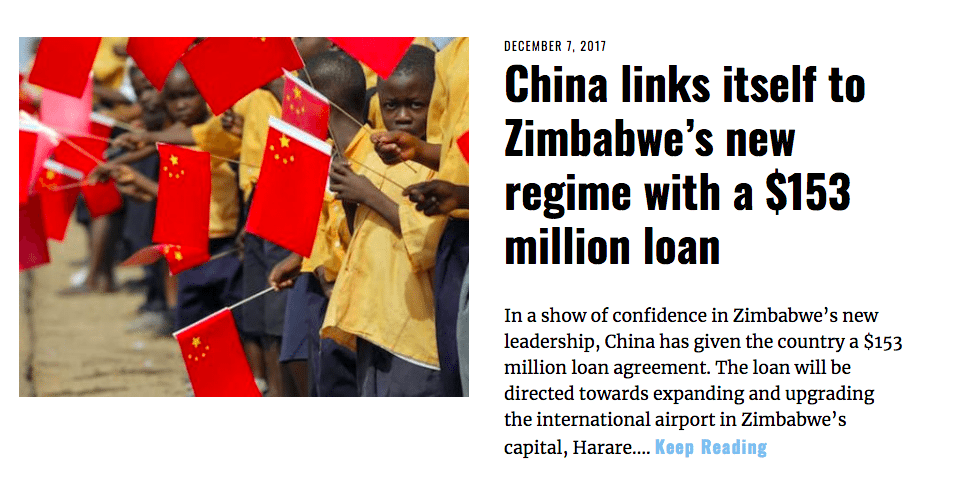

Pressure from foreign governments will also be intense. For Chinese President Xi Jinping, the export of Congolese minerals has been a cornerstone of his presidency. Just weeks after assuming office in March 2013, he conducted a state visit to the DRC, as China already had a substantial stake in the DRC’s mining operations. In 2007, a deal was struck between Sicomines, a consortium of Chinese companies, and the Congolese government to trade infrastructure investments for mining concessions in the country. The mines, which finally went online in 2015, were soon followed by Chinese state funds, billions of dollars in private investment, and a flood of Chinese immigrants.

Despite its promising beginning, the honeymoon period for China’s metal-for-infrastructure deal is now over. In October 2017, the Congolese government issued an order for Sicomines to halt all exports of cheap unprocessed copper and cobalt, demanding that the processing be done locally, but then mysteriously rescinded the order. Then, in November 2017, more serious doubts about the infrastructure promise emerged when it was reported that only $478 million of the $1.16 billion loaned to Sicomines was actually dispersed into development projects. The rest of the money that was loaned between 2008 to 2014 is unaccounted for.

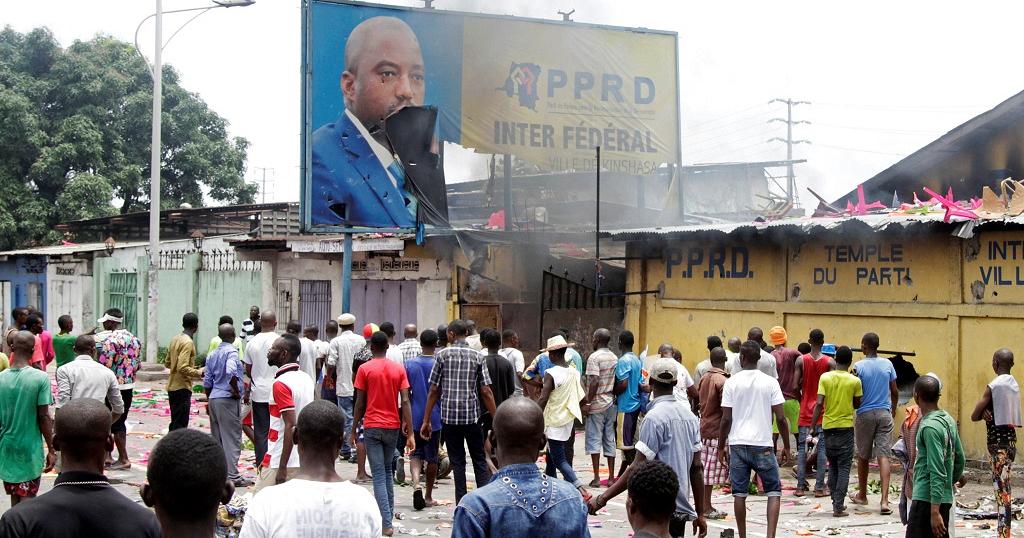

Simultaneous to all of this, DRC President Kabila’s political position within his country is faltering under continued protests. The DRC has been in a constitutional crisis since December 2016, when the president refused to step down following the expiration of his term. Elections that were scheduled for the end of 2016 have been delayed to the end of 2018, and citizens have not responded well to their president’s effort to stay in office.

President Kabila has made some strategic moves to secure his political position in Katanga for the interim. In early 2015, he split the province into four administrative units, which was viewed as an attempt to . Historically, divisiveness between those regional leaders has threatened the DRC, as they frequently attempted to split from the rest of the country. Mr. Kabila takes the threat seriously; so much so, in fact, that on Jan. 3, 2018, police surrounded the home of a former governor of Katanga the day after he declared his candidacy for the upcoming elections.

President Kabila is from Katanga, and the province has served as a base of support for his administration. But the decision to split the province has cost him dearly, with Katanganese politicians splitting from the ruling party and joining with the opposition. Opponents suspect Mr. Kabila may propose a referendum to change Congo’s constitution, which would to enable him to remain in office for future terms.

[Title Image: Amnesty International]

LIMA CHARLIE NEWS, with Diego Lynch and James Fox

Lima Charlie provides global news, insight & analysis by military veterans and service members Worldwide.

For up-to-date news, please follow us on twitter at @LimaCharlieNews

In case you missed it:

![Image The Rwandan Jewel - Peacekeepers, Conflict Minerals and Lots of Foreign Aid [Lima Charlie World]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/Rwanda-Jewel-480x384.jpg)

![image Resistance mounts against China's President Xi Jinping [Lima Charlie News][Photo: Johannes Eisele / AFP]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/Resistance-mounts-against-Chinas-President-Xi-Jinping-480x384.jpg)

![Image Little choice for Russia and China but to link up [Lima Charlie News]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/headlineImage.adapt_.1460.high_.russia_china_opinion_052114.1400674740238-480x384.jpg)

![Africa’s Elections | In Malawi, food, land, corruption dominate [Lima Charlie News]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/Malawi-election-Food-land-corruption-480x384.jpg)

![Image [Women's Day Warriors - Africa's queens, rebels and freedom fighters][Lima Charlie News]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/Womens-Day-Warriors-Lima-Charlie-News-480x384.jpg)

![Image Zimbabwe’s Election - Is there a path ahead? [Lima Charlie News]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/Zimbabwe’s-Election-Is-there-a-path-ahead-Lima-Charlie-News-480x384.png)

![[Silver lining for China in Zimbabwe’s violent elections][Lima Charlie News]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/Screen-Shot-2018-08-02-at-12.51.35-PM-480x384.png)

![Image The Rwandan Jewel - Peacekeepers, Conflict Minerals and Lots of Foreign Aid [Lima Charlie World]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/Rwanda-Jewel-150x100.jpg)

![image Resistance mounts against China's President Xi Jinping [Lima Charlie News][Photo: Johannes Eisele / AFP]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/Resistance-mounts-against-Chinas-President-Xi-Jinping-150x100.jpg)