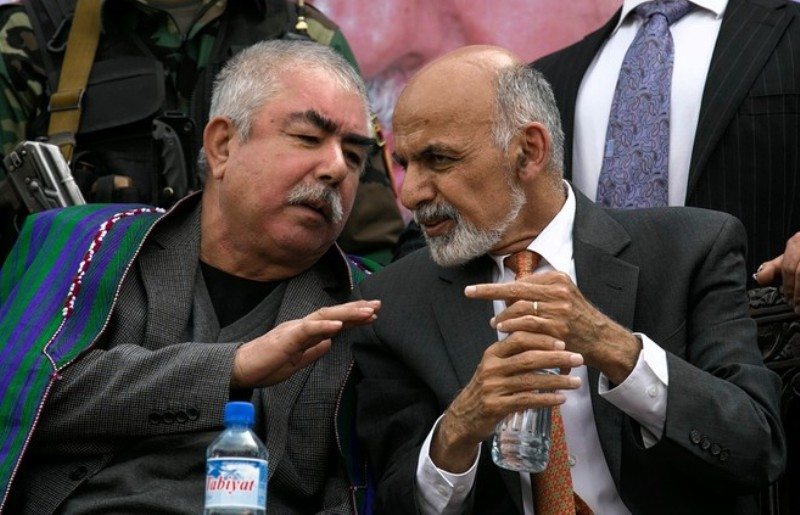

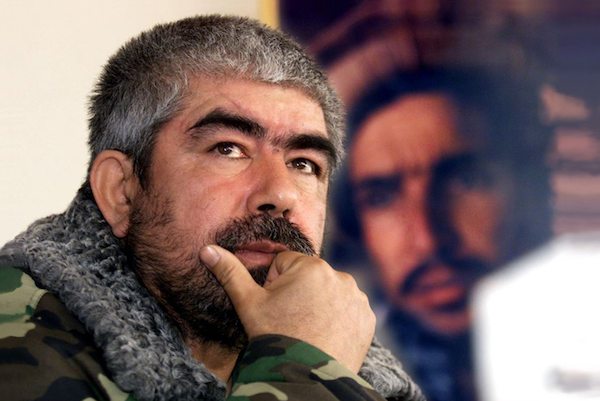

Afghanistan faces a power play between current President Ghani and legendary former warlord and general, Vice President, Abdul Rashid Dostum.

On July 18th, a small private plane chartered by the office of the Vice President requested landing permission at a government airport in the North of Afghanistan only to be redirected to land in Kabul. Onboard the plane was Vice President Abdul Rashid Dostum, and the order to refuse the landing came from the central Kabul government. Dostum smelled a rat and told the pilot to land in Ashgabat, Turkmenistan.

Officially, the Afghan authorities claim to have denied the request based on a technicality. Dostum did not inform them ahead of time of his return. At the same time Dostum, as First Vice President, has no obligation to ask permission to enter Afghanistan. Something was up.

It appears that the President of Afghanistan, Ashraf Ghani Ahmadzai of the Ahmadzai Pashtun tribe, is using the events as a relatively safe way to stall Dostum’s return, or force an agreement with him. Ghani is attempting to do this without upsetting the countless powerful local warlords that consider Dostum their ultimate representative in Kabul.

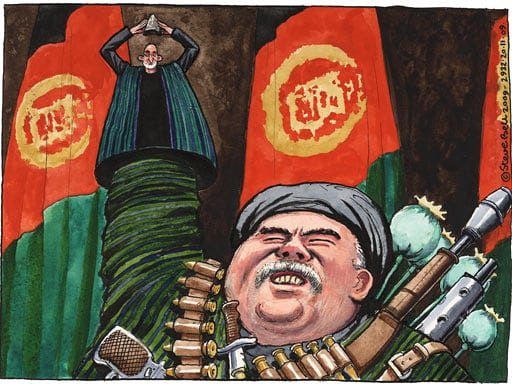

In recent months, Dostum has become an increasingly vexing thorn in the side of the stagnating Kabul government, both by publicly speaking out against his own President, but also by moving to create a competing coalition to the President’s. Considering the power dynamics in Afghanistan, it is not unlikely that Ghani is making an unmerited play to fulfill his campaign promises; chiefly ridding the Afghan government of corruption. While Dostum may not be directly corrupt, ultimately his power comes from the act of power-broking, influencing, and dominating, in a traditional Afghan style. The existence of Ghani’s quasi-democratic government would be utterly impossible had it not been for the coalition put together by Dostum, which involved all the key players and backing from abroad.

What seems to be forming is a perfect storm that in some ways mirrors the fall of the Soviet-backed President Najibullah in the early 1990s, after the Soviets withdrew, which saw Najib utterly relying on the military might brought by Dostum to keep him in power. Today, we see Ghani being utterly dependent on the mercy of General Dostum’s military power, and his political savvy.

Not a single individual has reigned over Afghanistan in the past 40 years without the endorsement of Dostum.

Abdul Rashid Dostum, an ethnic Uzbek, the current First Vice President of the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan, has been called many things. Dostum’s opponents, chiefly found in Kabul and the international community, fear him. His grassroots support within the ethnic community, the Afghan military and among regional power players has never waned.

There is an overall belief, or even hope, that Dostum’s reputation as the “kingmaker,” along with maker and breaker of alliances, may bode ill for the Western idea of a pliant Pashtun president. What Western observers, and possibly the current President of Afghanistan, forget is that it is impossible to govern present-day Afghanistan without the backing of tribal powers, and regional power players. Dostum largely controls Ghani’s access to those that truly hold power, and not a single individual has reigned over Afghanistan in the past 40 years without the endorsement of Dostum. In essence, Ghani appears to have forgotten not to bite the hand that feeds him.

In an effort to interfere with Dostum’s popular support, the opposition, both inside and outside Afghanistan, has taken every opportunity to smear him, to antagonize the slightest situations, and to fling whatever insult possible against him. This has resulted in an interesting situation where the vice president of Afghanistan remains in office, powerful as ever, but is now in de facto exile from the country.

Throughout the mid 80s, under the Soviet backed Afghan government, General Dostum was a rising star. He rose from Uzbek roustabout to command a 50,000 man-strong militia battalion deployed to rout out any anti-Soviet, United States-supported, Mujahideen. Under Dostum’s aggressive and fast-paced command, the battalion became the only Afghan Army group militia that could operate without Soviet oversight.

Dostum raised his force in the Afghan tradition, filling the ranks with rough hewn men chiefly from his own region and encouraging them to enjoy the spoils of victory. The “Carpet Grabbers’ were famous for winning and looting in Kabul. The militia group kept growing in ranks, until it reached regiment status, and was consolidated with the 53rd Infantry Division. The new division came under Dostum’s control, and he reported directly to the Soviet-backed President, a former head of state intelligence, Doctor Mohammed Najibullah. Even though Najibullah was much respected, without Dostum’s military support under the direction of KHAD, the Afghan intelligence agency Najib once headed, he would have quickly been overthrown by Pakistani based forces funded by United States (US) and Saudi governments.

Throughout the 80s, the forces under Dostum’s command continued to engage the Mujahideen, moving rapidly and defending key hubs throughout the country. But by the late 80s, the Soviet Union was running out of money and interest in defending Afghanistan from islamic insurgents.

To handle the situation, and allow for the withdrawal of their own units, the Soviets instituted a program to train around 400,000 international security forces. The training program for these newly recruited security forces were largely based on that of Dostum’s 53rd Infantry Division.

After spending between $36 to $45 billion dollars in Afghanistan, the withdrawal of Soviet troops was officially complete on February 15, 1989. And with that, it left the Afghan government in Kabul to fend for itself, with only small amounts of covert funding coming from Moscow. Like Afghanistan today, the Kabul government was utterly dependent on foreign money, skills and resources.

At this time Pakistan based and supported Afghan warlord Gulbuddin Hekmatyar set his sights on Kabul. Hek’s ambitions led Dostum to make an alliance with his former enemy Ahmad Shah Massoud, also known as the “Lion of Panjshir”. Under their agreement, Dostum and Massoud would seek to defend Kabul from Hek together.

Dostum and Massoud would be joined by Karim Khalili of the Shia-Hazera minority, an Iranian-backed warlord. Dostum provided helicopters and tanks to leapfrog the back country Panjshiri fighters into the heart of Kabul. However, by January 1992, the Soviets cut off funding as part of an agreement with the Americans to end their covert war, and by March President Najibullah resigned from office.

The post-Soviet years in Kabul are mostly lost to history and are perhaps the most turbulent ones for Afghanistan. Dostum and his band of loyal men initially joined Massoud in April of 1992, after arresting Najibullah, to battle Hekmatyar. Dostum and his, largely, Uzbek forces played a key part in preventing Hek’s total control of Kabul in 1992.

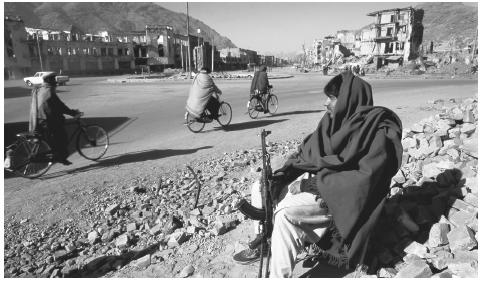

Until this point, the war had been fought in the countryside, leaving Kabul as a shining example of reconstruction and Soviet infrastructure planning. This is still evident in the ugly boxy apartments and government offices in Kabul. Massoud and Hekmatyar are credited with doing most of the destruction to Kabul, using stockpiled US-supplied weapons, during 1992.

By 1994, Dostum joined Hekmatyar against Massoud to prevent the complete destruction of Kabul. Kabul went from being merely a war-torn city in despair, to becoming a bedlam of daily street to street fighting. This led to an attempt by some to pit Afghan against Afghan to completely destroy what remained of the capital. Throughout the country, whatever trace there was of a centralized government vanished. Disgusted, Dostum’s men finally fought their way out of Kabul and returned to the North. Dostum created a state within a state issuing his own currency, even having his own airline.

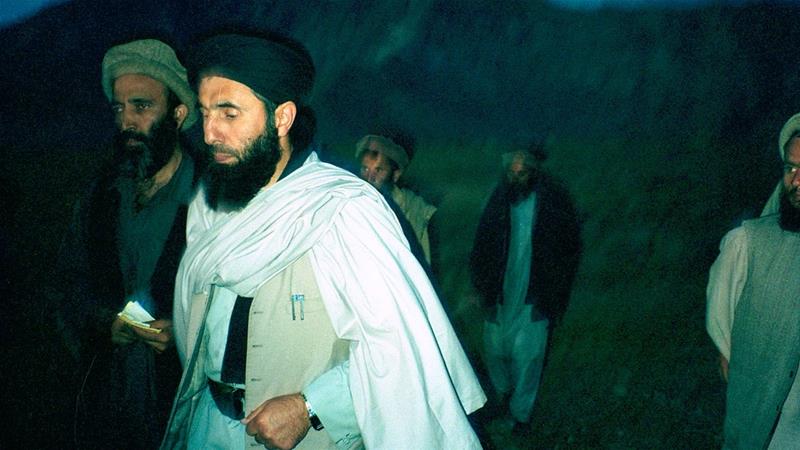

In this chaos, by 1994, a small group of Mujahideen with more extreme beliefs emerged in the refugee camps in southern Pakistan. The new group called themselves the “taliban”, the plural of religious students. They were recruited out of madrassas and led by thirty Mujahideen to clear the roads and get rid of the warlords in the south.

The Taliban captured positions and provinces without firing a shot using Pakistani and Saudi money. They also carried out a diplomatic offensive by creating the “Peshawar Accord”, a power-sharing agreement between the new invaders and aligned tribal groups in the south. Local tribes would retain control of their areas in exchange for sharing income and security. Through success, and religious dogma, the group quickly grew and became a noticeable ground force.

By 1996, the Taliban had entered a devastated Kabul, the strange westernized landscape that became an affront to their 7th century view of the world. TVs were smashed, cassette tapes gutted and women were forced to cover their faces. The direct conflict with the comparatively wealthy NGOs resulted in a Western PR campaign, which forever branded the Taliban as the enemy. Journalists were given one day tours to decry the lack of education for women, the wearing of beards and even Friday executions at the Olympic themed Kabul Stadium. The message ignored that US-backed Hekmatyar was far more backward and primitive than the Taliban. Under Taliban rule, Kabul saw the first lull in fighting since the Soviets left.

With Kabul largely under Taliban control, Kabul settled into a calm but primitive dystopian center. Their control over Kabul quickly grew so absolute that, on the eve of September 26 1996, they were able to walk into a secure United Nations compound in Kabul, which was providing a safe haven for the former President, Dr. Najib, without firing a single shot. Once inside, the Taliban fighters, sent there on the personal order of the Taliban leader, Mullah Mohammed Omar, beat and tortured Dr. Najib mercilessly in front of UN personnel. With the former President inches from death, he was tied to the back of a pickup truck, and dragged down Kabul streets. Dr. Najib’s brother, Ahmadzai, who had been staying at the UN compound was given much the same treatment, with the kindness of a bullet to the head first.

Now they had to decide what to do with the north, an alien territory for the Pashtun group. The group quickly decided on a draconian campaign of scorched earth. They began airlifting Pakistani and Afghan fighters into Kunduz every 20 minutes while a motorized ground force swept to the west killing and burning villages as they encountered severe resistance.

Dostum, who had fought his way out and abandoned Kabul after he saw the destruction created by Massoud and Hekmatyar, rejoined his old foes against the Taliban. Dostum, Massoud and Karim Khalili created the Northern Alliance in 1996 to combat the encroaching mullahs. Massoud was able to hold out but Pakistani money bought off Massoud’s number two commander forcing Dostum to flee to Turkey. By 2001 a few of Dostum’s men held out in the mountains while Massoud was getting funds from the Central Intelligence Agency and Iran to hold on.

The overt, and bloody, first civil war in Afghanistan raged between 1992 to 1996, and ended with the Taliban declaring Kabul the capital of their Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan. The Taliban Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan operated alongside the internationally recognized, albeit failed, Islamic State of Afghanistan between the 1996 to 2001.

Numerous attempts to take out Bin Laden by the CIA were overridden by Clinton and Bush, largely due to concerns over displeasing the Saudis, which might have led to the cancelling of arms sales.

Osama Bin Laden, who had arrived in 1996 to create a base of operations for himself in Jalalabad, felt threatened by the ongoing conflict, and in need to establish himself. Through his Talib minders, he was encouraged to move to Kandahar, where he joined the Taliban.

To create a power bloc to call his own, Bin Laden created an Islamic mercenary outfit, which provided the Taliban with thousands of recruited, vetted, trained and armed foreign fighters, all funneled into the country under the supervision of the Pakistani Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI). It was this outfit that would soon become known as the al Qaeda militant group. Bin Laden, along with other criminals on the run, began to hatch international plots culminating in a “fatwa” that declared war on America issued from Afghanistan.

Media outlets were marched up to the Bin Laden compound in Tora Bora, an unassuming set of wood and brick-mud houses with a small playground for the family of Bin Laden’s bodyguards, to interview Bin Laden as he declared jihad on Western powers. This was disconnected from the goals of the Taliban who simply wanted to remove outside influence.

Numerous attempts to take out Bin Laden by the CIA were overridden by Clinton and Bush, largely due to concerns over displeasing the Saudis, which might have led to the cancelling of arms sales. This was despite the general knowledge that Bin Laden’s group was largely furnished by Saudi money, and used to channel Arabic speaking fighters under an al Qaeda black banner. Throughout the mid to late 90s, the group carried out a series of Jihadist activities in Africa, and the Middle East, and after being kicked out of Khartoum, they were in need of a safe haven.

After Bin Laden moved to Kandahar he began to flatter Mullah Omar and portray him as the Emir of an international movement. The Taliban leadership, headed by Mullah Omar, was keenly interested in what Bin Laden’s ragtag group could bring to the table in exchange for said safe haven. Not coincidently the Taliban’s rule over Afghanistan was only recognized by the Emiratis, Saudis and Pakistanis, while the faltering “Northern Alliance”, and their Islamic State of Afghanistan, was still recognized as the official government by the international community.

Under President Bill Clinton several options were investigated as to how to neutralize the al Qaeda leadership. One of the options proposed to Clinton was a novel idea by the technical directorate of the CIA; to build an armed unmanned aerial vehicle that could launch a missile against the Bin Laden compound. The proposal was not carried out because of technical misgivings, and the president’s hesitation to carry out an attack on a compound that had women and children within it.

Meanwhile, the Northern Alliance, as led by Dostum and Massoud, continued fighting the Taliban and their affiliated forces. Massoud’s positions in Mazar-i-Sharif had been lost amidst a series of full scale infantry attacks by Taliban-affiliated forces. The group’s positions throughout the entire country appeared exposed. The infighting within the group was quickly further straining operational capabilities. One of Dostum’s main competitors for power, General Abdul Malik Pahlawan, entered into secret negotiations with the Taliban to rid himself of both Dostum and Massoud. The Taliban quickly offered Malik control over Northern Afghanistan in exchange for the cessation of hostilities, and the removal of key opponents.

Malik began moving against the Northern Alliance, and his former allies. This act of treason forced several key members of the Northern Alliance to utilize their lifelines with American and Middle Eastern intelligence agencies, going into exile to protect themselves from assassination attempts by men aligned with Malik. As Malik followed through on his promises to the Taliban, he soon realized that the Taliban had little intent of following through on their part of the Faustian bargain as they began to disarm his people.

Malik’s forces joined with Dostum’s forces, attacking the Taliban positions in Mazar-i-Sharif slaughtering thousands of Talibs and dumping their bodies in a desert location known as Daesh de Leili.

On September 9th, 2001, Dostum’s close ally, and now friend, Ahmad Shah Massoud, was assassinated by two North Africans pretending to be from a Belgian news organization. A suicide bomb hidden inside a battery belt for a film camera killed Massoud. The next day a coordinated attack was launched against the Panjshir front lines. Two days later 9/11 brought Bin Laden and the unwitting Taliban directly into America’s cross hairs.

With Massoud dead, Dostum became the principal leader of the Northern Alliance. Massoud had diverted a few thousand dollars of CIA funds to fly Dostum and his inner circle to the Panjshir and to create a second front in the Daryi Suf. The CIA refused to work with Dostum, but the US Army Special Forces command, based out of the southeastern Uzbekistan Karshi-Khanabad air base, better known as K2, demanded that either the Agency and its Special Activities Division (SAD) go in, or the Special Forces would go in without them.

When Operational Detachment Alpha (ODA) 595, a part of the Army 5th Special Forces, arrived a few hours after the CIA SAD unit, Dostum was already attacking the Taliban lines in force. After a rocky start, the US commandos were able to coordinate B 52 air strikes with horse mounted charges to create one of the most iconic chapters in American military history. The Taliban surrendered to Dostum and the CIA 3 weeks later.

Part of the Army Special Forces plan to retake Kabul, drive the Taliban out, and to find Osama Bin Laden was a State Department plan to install a relatively unknown Pashtun named Hamid Karzai to power. Dostum was considered a threat to this plan, even though on the battlefield, Dostum had just captured over 3000 Talib and Pakistani fighters alive. Dostum and his small contingent of US Advisors had been cheered on by weeping Afghans as they entered liberated towns. Dostum had shown that he was a master of war in Afghanistan. The US State Department’s plan, however, was to keep minority groups like the Panjshir and Uzbeks out of Kabul to give them time to install a pliant, Pakistani friendly Pashtun leader.

Not coincidentally, in late 2001 Dostum’s forces were accused by selected media outlets of intentionally suffocating nearly 2,000 Taliban soldiers in container trucks. The bizarre story was based on anonymous sources who pointed to the Taliban burial ground in Dasht-i-Leila. Despite the accusations, no serious investigation was ever made. A series of stories, planted by interest groups in Washington D.C., about Dostum’s reputation as a brutal warlord, cemented his new reputation in the Western media.

With Dostum sidelined, America began its attempt at state building in Afghanistan. President Hamid Karzai, bereft of an Army or grassroots support, was installed by jirga, a traditional assembly of Pashtu tribal leaders. However behind the headlines touting his popularity, Karzai would need Dostum’s swing vote to get elected twice.

Various attempts to unseat Dostum were raised to farcical levels. Rival Turkic candidate, and drug dealer, Akbar Boi insisted that Dostum had raped him with a beer bottle. Dostum, disgusted by the Kabul political scene and its games, simply moved his operations to Turkey until Karzai begged him to return to help him get elected in the North. Flush with election funds, Dostum’s Junbesh party ran Karzai’s election campaign, and was firmly re-installed in Kabul.

Thousands of supporters greeted Dostum as he arrived in his northern stronghold of Sheberghan. During a speech given at a stadium there, he stated that he could “destroy the Taliban and al Qaeda” if supported by the US, saying that “the US needs strong friends like Dostum.” The Obama-era US Ambassador to Afghanistan, Karl Eikenberry, an academically inclined retired United States Army lieutenant general of the political school, warned that Dostum’s presence in the country could “endanger much of the progress made in Afghanistan.” Up until then, the regions controlled by Dostum along with the other minority groups had been resistant to Talib insurgency, yet the State department still pursued the racist policy of supporting candidates from the majority Pashtun tribe.

During the 2014 Afghan General Election, Dostum, sensing that Karzai’s horse was nearly dead, chose American banker Ashraf Ghani Ahmadza, of the Ahmadzai Pashtun tribe, as his running mate. Ghani had little support and Dostum put his political machine into high gear.

Dostum, as expected, received serious backlash from monitoring groups and humanitarian rights groups, while Ghani was revered as being ideal. The victory of the duo was nearly guaranteed. With Ghani winning the election in a landslide victory, Dostum became the Vice President of Afghanistan. This time, the US Government did not make a public statement regarding Dostum, instead praising the election as an example of a peaceful transfer of power.

However, US State Department memos from the time, leaked through WikiLeaks, make it clear what the US State Department thought of the man. They referred to Dostum as “Afghanistan’s quintessential warlord.” The thoughts of US State Department representatives in Kabul stood in stark contrast with how Dostum was otherwise perceived, by international operators and locals alike, as pro-American, pro-(relatively speaking) women’s rights, and the goto man to fight the Taliban movement. The Agency began working with Dostum again, but he remained largely persona non grata (PNG) by the State Department and non-intelligence/special operations communities inside the military.

This divergent and disconnected treatment led to a near schizophrenic approach by the US to Afghanistan. The question was whether to work with a proven enemy of the Taliban with ground support, or support an effete technocrat using a manufactured army. This scenario was eerily reminiscent of the situation that former President Dr. Najib faced in the early 1990s.

In May 2017, history again repeated itself. Accused of rape and abuse by a longtime rival, Dostum again found himself under attack by elements that wanted to replace him as head of the minority party, Junbesh.

The charges were near mirror images of those Dostum faced in 2008. Ahmad Ishchi, a political rival of Dostum’s for 3 decades, accused the Vice President of having him abducted during a sports event. According to Ishchi, he spent 5 days being tortured, abused, even being sexually assaulted with an assault rifle at one point, by Dostum’s men, before being handed over to local intelligence officers. The intelligence officers in turn are said to have held Ischi a further 10 days. During the described time period, Dostum was seemingly acting as President, as Ghani was out of the country.

Multiple witnesses describe a particular incident that occurred between Dostum and Ishchi before the abduction at a local Buzkashi game. Ishchi deliberately enraged Dostum after he called him out for sobbing in response to the names of recently killed friends being read out at the game. Dostum strode out to the field, knocked Ishchi down and put his boot on his throat. The Vice President’s bodyguards, seeing Ishchi insulting the Vice President, dragged Ishchi away and beat him. Ishchi’s claim that he was abducted appears to be true, as do his claims to have been beaten by the Vice President’s bodyguards.

What Ishchi failed to mention, while he decried his treatment and the Vice President along with it to the Afghan media, was that he spent most of his time being interrogated by the National Directorate of Security (NDS), the Afghan intelligence, over his intercepted phone contacts with Taliban groups in the north.

During the same time period, Dostum just narrowly survived an ambush that he strongly believes was planned by the NDS. Dostum lost 80 of his own men in hand to hand combat with elements from the very same NDS force that was sent to protect him. As Ishchi’s highly inflammable remarks got their expected media traction, Western donors and NGOs were in immediate, and seemingly coordinated, lockstep with the developments.

Dostum’s reaction was utterly predictable. He quickly formed a new alliance, which included Atta Noor, Mohaqiq and other alienated minorities. This new coalition has the potential to derail President Ghani’s chances in the upcoming election. In essence, it appears that Dostum’s play is to make a move towards high office, and Ghani, who has recently adopted the Karzai label of “Mayor of Kabul”, is responding by attempting to block the move.

The Vice President’s office released a public statement calling the accusations a conspiracy to defame the office. Internally, their funds have been cut off and Dostum was not consulted on any key decision-making.

During this latest of self imposed exile, Dostum has played the role of John Galt, showing the government what happens when you remove your support. Biding time in Turkey has allowed Dostum to privately contemplate his next move.

In this never ending game of shahmut, or what we call chess, it is now Ghani’s move.

John Sjoholm and Joe Kassabian, Lima Charlie News

[Edited by Anthony A. LoPresti]

John Sjoholm is Lima Charlie’s Middle East Bureau Chief, Managing Editor, and founder of the consulting firm Erudite Group. A seasoned expert on Middle East and North Africa matters, he has a background in security contracting and has served as a geopolitical advisor to regional leaders. He was educated in religion and languages in Sana’a, Yemen, and Cairo, Egypt, and has lived in the region since 2005, contributing to numerous Western-supported stabilisation projects. He currently resides in Jordan. Follow John on Twitter @JohnSjoholmLC

Joe Kassabian is a Veteran of the US Army, serving for seven years as a 19K and is a published Author. He has worked extensively in the Middle East, Europe, and South Asia training and advising national security forces. He studied Communications and Journalism in Texas before relocating to the Seattle area. His first book, a memoir of his last year in Afghanistan, The Hooligans of Kandahar, is available now in paperback and ebook. Follow Joe on Twitter @jkass99

Lima Charlie World provides global news, featuring insight & analysis by military veterans, intelligence professionals and foreign policy experts Worldwide.

For up-to-date news, please follow us on twitter at @LimaCharlieNews

In case you missed it:

![Image Strike a deal with which devil? The many faces of the Taliban [Lima Charlie News][Image: Anthony A. LoPresti]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/Many-faces-of-the-Taliban-Lima-Charlie-News-Anthony-LoPresti-480x384.png)

![Image The fate of Afghanistan’s NATO Generation [Lima Charlie World][Photo: Shamsia Hassani]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/The-fate-of-Afghanistan’s-NATO-Generation-Lima-Charlie-World-Shamsia-Hassani-480x384.png)

![Image Afghanistan – A Bold Solution [Lima Charlie News]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/Afghanistan-A-Bold-Solution-Lima-Charlie-News-480x384.png)

![Image Strike a deal with which devil? The many faces of the Taliban [Lima Charlie News][Image: Anthony A. LoPresti]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/Many-faces-of-the-Taliban-Lima-Charlie-News-Anthony-LoPresti-150x100.png)

![Image The fate of Afghanistan’s NATO Generation [Lima Charlie World][Photo: Shamsia Hassani]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/The-fate-of-Afghanistan’s-NATO-Generation-Lima-Charlie-World-Shamsia-Hassani-150x100.png)