Between the mansions of Beverly Hills and the beaches of Santa Monica, a 400-acre plot of land belonging to the Department of Veterans Affairs is quietly falling apart, inside and out.

The West Los Angeles VA Medical Center is surrounded by wealth: Porsche dealerships, private schools, even two Whole Foods. But behind the glitz and glam, the homeless population of military veterans in Los Angeles is doubling. Today, there are approximately 4,800 homeless former service members in L.A. County, which, besides being the largest count in any major U.S. city, is a 57 percent increase since 2016.

Nearly 300 beds and programs have been disbanded or moved off of the West Los Angeles VA campus over the last year, despite the medical center’s growing budget, which currently stands at nearly $1 billion. To compound the problem, Lima Charlie News has discovered a pattern of mismanagement and a toxic leadership that has caused over 50 staff psychiatrists to leave since 2015 alone.

An Old Soldiers Home

The VA West Los Angeles Medical Center has been around nearly as long as the state of California itself. Following the Civil War, in one of the last Acts signed by President Lincoln, Congress passed legislation to incorporate the National Asylum for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers and Sailors of the Civil War. It soon became known as “the Old Soldiers Home,” and by 1887, Congress approved the establishment of a Pacific branch near Santa Monica. When several hundred acres of property were donated to the VA in 1888, it was meant to be a place for service members to adjust to civilian life. Known as the Sawtelle Veterans Home, the campus had a church, a post office, even a street car to shuttle people around the sprawling property. It functioned like this for nearly a century. At its peak during the Korean War, the campus housed nearly 5,000 veterans.

In the 1970’s, however, the original mission of the West Los Angeles VA was lost. More attention was put into healthcare and research as demand increased, and a modern hospital was eventually built on the campus in 1977. The facility that used to take in thousands of war veterans fell into disrepair.

Valentini v. Shinseki: The Lawsuit over Leases

Because of the size and location of the VA campus, there has been a long and contentious history of commercial businesses and organizations using it for non-veteran purposes. Beginning in 2001, the West Los Angeles VA granted nearly a dozen leases, including contracts for an Enterprise Rent-a-Car, a UCLA baseball stadium, and an athletic complex for a Brentwood private school. There were also land use agreements for a Marriott hotel laundry facility and a school bus parking lot.

None of these leases had anything to do with veterans, and although they did bring in money, it was never made clear how that money was being invested back into the campus. According to documents obtained by NPR through the Freedom of Information Act, it is estimated that the VA West Los Angeles Medical Center took in between $28 million and $40 million over more than 10 years.

In 2011, the ACLU of Southern California filed a lawsuit against then-VA Secretary Eric Shinseki and the VA Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System, alleging that the West Los Angeles VA had misused its land while ignoring the housing needs of homeless veterans. Two years later, a federal judge ruled the leases to be “unauthorized by law and therefore void,” explaining that the VA had abused its power by leasing land for purposes “totally divorced from the provision of healthcare.” While the leases weren’t terminated overnight, the VA has spent the last two years trying to untangle itself from all of the contracts and deals that it made with outside businesses.

Valentini v. Shinseki resulted in what became known as The Master Plan, which was essentially a blueprint for how improvements would be made at the VA medical center over the next decade. Written alongside multiple advocacy groups, legislation for The Master Plan was passed over a year ago, yet it appears little progress has been made so far.

A “Toxic” Environment

Despite assurances to veteran advocacy groups of multiple reforms and programs in the wake of the lawsuit, gaps in veterans services have continued to emerge within the West Los Angeles VA. Over the last three years, nearly 50 psychiatrists have resigned or retired, out of a total staff of only 79 doctors.

“I’ve never heard of a place losing more than 50 people–really good people,” said Dr. Thomas Garrick, who resigned from the VA in 2017. “I was there 37 years. I was a professor at UCLA. I published 87 or 88 peer-reviewed articles, and I ran the whole psychosomatic medicine fellowship.” But for Garrick, the structural upheavals in the mental health division of the VA were too much to handle, and when his supervisors began trying to “dismantle” the fellowship he created, he left the VA to teach at USC.

Another psychiatrist at the West Los Angeles VA, Dr. Pamela Diefenbach, resigned from the West Los Angeles VA in 2015 to take a position with Kaiser Permanente. “I was a lifer at the VA,” she said. “I wanted to have a career there, but [they] do not respect people like me enough to keep us around. I felt dead … I was worked to the bone … so I got a job at Kaiser Permanente. When you look at the Long Beach VA Medical Center, things are great there. It’s the same with Sacramento. But the West L.A. VA … I couldn’t take it anymore.”

There are serious concerns regarding veteran care and this is due to staff resignations, vacancies and lack of immediate action.

Some of these problems are rooted in a restructuring of the mental health department made in the wake of the 2014 national scandal involving the VA’s failure to make timely appointments and provide care to veterans. However, as Dr. Garrick observed, “part of the problem is how Barry Guze treats other people.”

Dr. Barry Guze is the Associate Chief of Staff for Mental Health and the Chief of Psychiatry at the VA hospital. Numerous sources have cited him as a key factor in the facility’s upheaval.

Complaints against Dr. Guze were the driving force behind a 2015 internal VA investigation, the result of which was a document titled the Cook-Landreth Report. The report, which was recently obtained by Lima Charlie News, suggests that Dr. Guze’s repeated actions “caused great turmoil, a substantial waste of resources, and frustration and low morale among the staff.” VA psychiatrists also told investigators that “there are serious concerns regarding veteran care and this is due to staff resignations, vacancies and lack of immediate action.” Initial comments to a 2015 draft of the Master Plan further highlight these complaints.

The Cook-Landreth Report gave Dr. Guze’s supervisors 12 recommendations for addressing these problems, which included site visits, regular consultation meetings, and phone calls with the VA Office of Mental Health Operations in Washington D.C. A spokesperson for the VA has told Lima Charlie News that “all 12 recommendations [in the report] have been completed,” although the VA has, thus far, been unable to provide further details or documentation to substantiate that. And, while some vacant positions at the VA have recently begun to be refilled by young UCLA psychiatrists, former staff like Dr. Garrick and Dr. Diefenbach say the breadth of talent and experience that has been lost is immeasurable.

As a result of so many resignations and staff departures, multiple clinics have either been overwhelmed or diminished, including the Domiciliary, which provides mental health services to homeless veterans. According to two VA psychiatrists who work with homeless veterans in Los Angeles, the Domiciliary at the West Los Angeles VA Medical Center had zero psychiatrists working there for multiple months in 2016 and 2017, amidst an epidemic of veteran homelessness that continues to grow worse.

Today, Dr. Guze remains the Chief of Staff for Mental Health and the Chief of Psychiatry at the West Los Angeles campus, despite the investigation’s conclusion that his “lack of VA Leadership experience has created gaps in veteran treatment.”

While doctors and staff at the West Los Angeles VA continue to grow more frustrated with the toxic workplace environment and personnel shortages, they frequently say that it’s the veterans that are being hurt the most.

“Things are getting worse and worse,” said Sergeant Pablo Agrio, a veteran currently living at Hope Harbor, a Salvation Army shelter south of Downtown Los Angeles. He’s bounced between VA programs and private shelters since being released from prison in April 2017, and has seen programs disappear in a matter of months. He was finishing his last day of work therapy when he sat down to talk, unsure of what was to come at 60 years old.

The Dom, or the Domiciliary Care Program, is the VA’s oldest healthcare and rehabilitative program and is currently located in Buildings 214 and 217 on the West Los Angeles VA campus. The program is meant to provide clinical rehabilitation and mental health services to veterans, although it has faced staff shortages since at least 2015, according to multiple VA sources, resulting in reduced services and excess wait times.

Although Mr. Agrio said he hasn’t noticed severe understaffing at the Dom, he did say eligibility for the program has become extremely selective as mental health and housing services decline, which has left a lot of veterans, like himself, to fend for themselves in a complex bureaucracy.

“The VA is fantastic in terms of healthcare,” he said. “I mean, I raise my hand and I say my little pinky hurts and I’m in like that. I need glasses–I get ‘em. I need boots–I get ‘em. But if I say I need somewhere to live, that’s where things fall apart. They say you have to go to SSVF or you have to go to HUD-VASH, and I quickly realized, ‘heck, I don’t qualify for any of these!’”

Supportive Services for Veteran Families (SSVF) and Housing and Urban Development-VA Supportive Housing (HUD-VASH) are two programs that help veterans pay for permanent supportive housing through vouchers and financial aid. The likelihood of qualifying for a program like SSVF, however, is quite low. Because the program requires that a veteran and his family all be in need of assistance, only 395 veterans, or 1 percent of the country’s total homeless veteran population, received SSVF benefits in 2016, according to a VA report.

As for HUD-VASH, the program says that in order to receive assistance, a veteran must be chronically ill, mentally ill, or have substance abuse problems. While all of those conditions are becoming more common as troops return from Iraq and Afghanistan (roughly half of all homeless veterans have a mental or physical disability), veterans without a severe disability, like Pablo Agrio, are falling through the cracks of the VA system.

Since 1994, The Salvation Army has run multiple programs on the grounds of the West Los Angeles VA, including the Haven, which provides transitional housing to veterans that haven’t been placed into a more permanent option. Unlike SSVF or HUD-VASH, The Salvation Army operated on the West Los Angeles campus through a “Grant and Per Diem program,” which allowed the agency to apply for grants from the VA to provide beds and meals to veterans on the West Los Angeles campus.

That is, up until Sept. 30, 2017, when the Salvation Army’s enhanced-use lease with the West Los Angeles VA was terminated, forcing all of its programs and nearly 200 beds to transfer to different parts of Los Angeles. One housing initiative, called the Haven program, was moved 22 miles away to Bell Shelter.

Ann Brown, director of the VA Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System, stressed that the decision to push the Salvation Army off the campus was based on performance issues. But when asked for further details, Ms. Brown, who lives in a gated “Governor’s Mansion” on an expansive compound on the VA property, did not respond to our request.

“I was disappointed–very disappointed,” said Mr. Agrio about the Haven being moved off campus. He believes the Salvation Army was kicked off, not moved off. “I think those people bent over backwards to help the vet, and they basically had an open-door policy. They didn’t turn anybody down no matter the time or day. And they would work with you. That’s the biggest difference between what the VA does for you and what the Salvation Army does for you. Here, you have to go through so many hoops before you actually see any help.”

1,200 units of permanent supportive housing promised after the Valentini v. Shinseki lawsuit have yet to be built.

Promised help has yet to arrive

While there has never been an expectation that the West Los Angeles VA would provide enough on-site housing for all of the city’s homeless veterans, 1,200 units of permanent supportive housing promised after the Valentini v. Shinseki lawsuit have yet to be built, despite legislation for the plan having being passed.

“When you have [veterans] in housing,” Kane said, “use of ERs, use of medical services, unnecessary inpatient hospitalizations — whether it’s for medical care or psychiatric care — incarceration, all those things go down.”

Additionally, permanent supportive housing can leave veterans with one less thing to worry about as they hunt for a job, get an education, or receive medical and mental health care at the VA.

These 1,200 units of housing will be a welcome addition for many vets struggling to get on their feet, but the first apartments will not be ready until 2022 at the earliest. This has left some veterans on the street wondering why the VA eliminated the transitional housing programs before the permanent housing was even built.

“Years ago yeah, terrible, terrible, like a city within a city,” Mr. Green added, as he graciously accepted a dollar bill handed to him by the driver of a tinted Range Rover. “I’ve seen guys jump another guy and take his shoes off his feet in broad daylight,” he said. “Two guys tried to jack me one time. When they see you with a lot of bags, they know you got money — that’s the cue. So they followed me for a couple blocks. And if the bus didn’t come when it did … I don’t know, it still scares me.”

“None of the Master Plan housing units have been built yet,” Mr. Perkins said in a telephone interview in January. “Environmental evaluations must be completed first, and those began in July [2017].” Those evaluations are scheduled to take 24 months, he explained, which means construction on new housing units cannot even begin until July 2019.

Currently, there is only one bloc of finished housing on the campus, with a total of 65 units. Still, some of those units sit vacant, according to Gabor Weibl, a veteran who currently lives in the building.

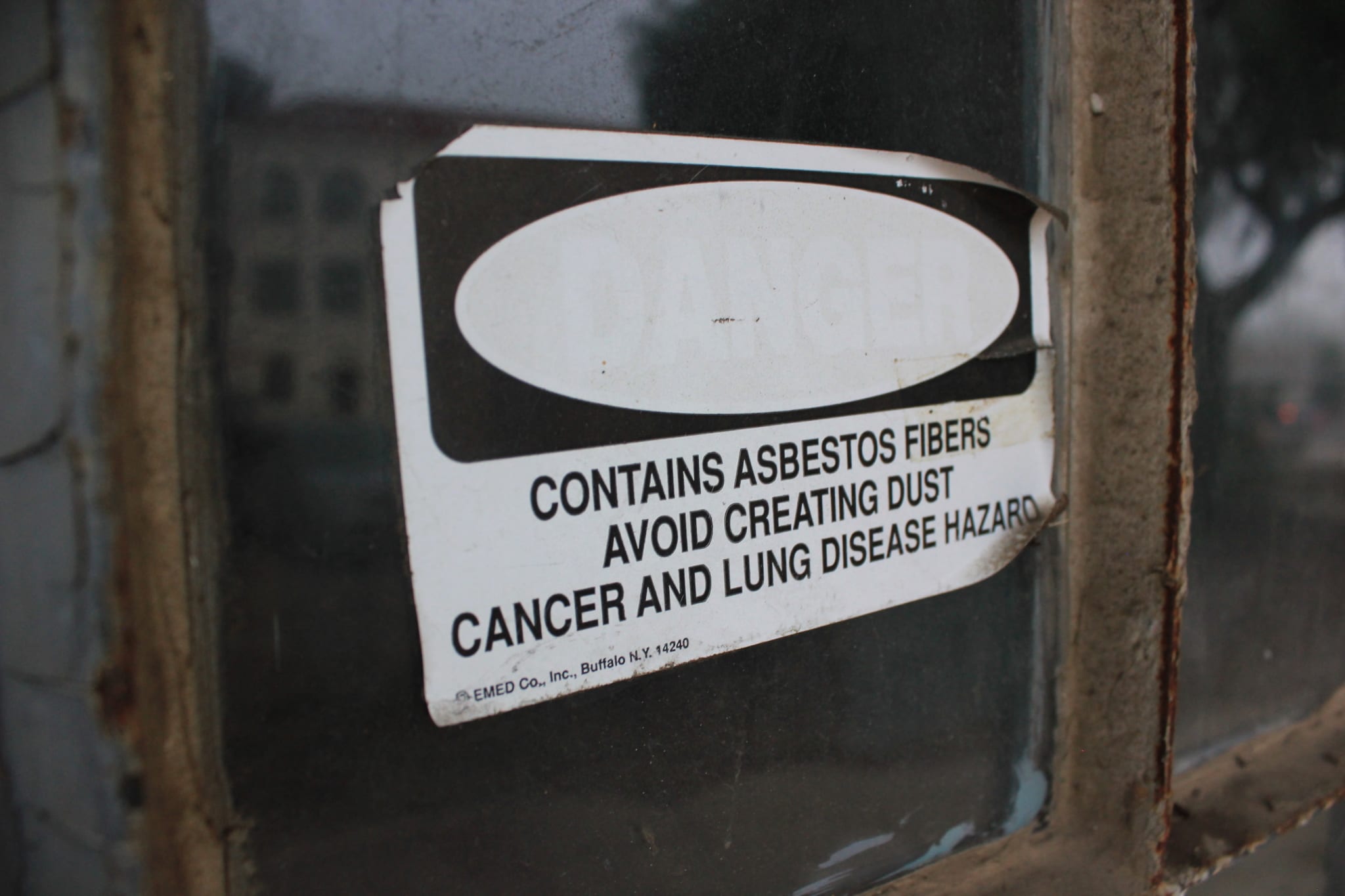

Two other buildings–205 and 208–are currently vacant and uninhabitable. Multiple windows remain shattered after a dead tree fell against the building last year. Squirrels run in and out of the entrances which are left open, day and night. Menacing asbestos stickers warn visitors not to get too close.

VA Director Ann Brown and Heidi Marston, head of the Community Engagement and Reintegration Services team, say construction on the West Los Angeles VA Master Plan will accelerate once the initial barriers are out of the way. Finding the land to build the housing units has never been an issue, nor has funding, as the VA’s budget continues to grow every year.

So, with nearly a decade remaining until the plan is scheduled to be completed, a lack of housing and mental health services has made many veterans, who risked their lives on the front lines, feel as if they’ve suddenly been left behind on a different kind of battlefield.

By James Fox, with David Max Korzen, and Melissa Etezadi, LIMA CHARLIE NEWS

If you would like to place a tip about this story to our team of investigative reporters, say it Loud and Clear here: tips@limacharlienews.com

Lima Charlie provides global news, featuring insight & analysis by military veterans, intelligence professionals and foreign policy experts Worldwide.

For up-to-date news, please follow us on twitter at @LimaCharlieNews

In case you missed it:

![Image At L.A. VA, Toxic Culture and Mismanagement Puts Veterans On The Street, Doctors Say [Lima Charlie News]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/WESTLAVA-1.jpg)

![Image Memorial Day may soon be a remembrance of democracy and those who had the courage to defend it [Lima Charlie News]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/Memorial-Day-may-soon-be-a-remembrance-of-democracy-and-those-who-had-the-courage-to-defend-it-Lima-Charlie-News-480x384.png)

![A Trump war crime pardon dishonors us all [Lima Charlie News]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/A-Trump-war-crime-pardon-dishonors-us-all-Lima-Charlie-News-480x384.png)

](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/Remembering-Becket-A-mothers-search-for-answers-480x384.png)

![The Mind of Bolton - AUMF and the New Iran War [Lima Charlie News]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/Inside-the-mind-of-Bolton-Lima-Charlie-News-main-01-480x384.png)

![Image Memorial Day may soon be a remembrance of democracy and those who had the courage to defend it [Lima Charlie News]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/Memorial-Day-may-soon-be-a-remembrance-of-democracy-and-those-who-had-the-courage-to-defend-it-Lima-Charlie-News-150x100.png)

![A Trump war crime pardon dishonors us all [Lima Charlie News]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/A-Trump-war-crime-pardon-dishonors-us-all-Lima-Charlie-News-150x100.png)