On Monday, May 30, 2016, Memorial Day, the non-profit organization The Greatest Generations Foundation took ten WWII veterans back to Normandy, France, to return to the battlefields they fought on, enabling closure of their war experiences. Among those heroes is veteran Douglas Dillard (82nd Airborne, 551 PIR). This is his story.

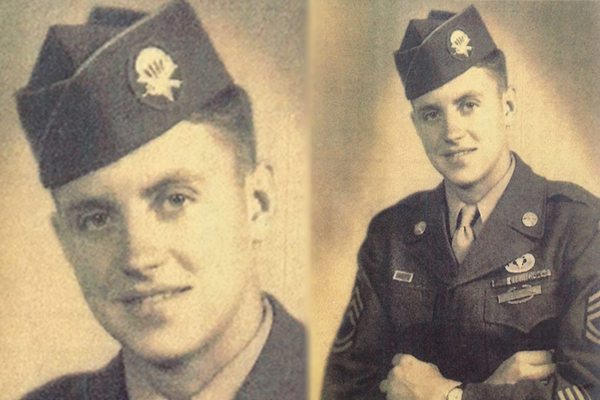

There are men and there are real men. My Lima Charlie colleague Rob Swain and I were recently given the honor of sitting in an interview with the legendary Colonel Douglas Dillard. I was even given the opportunity to ask him a few questions. Colonel Dillard is a 35-year combat veteran with overseas service bars lined-up to his elbow and more decorations than any soldier could imagine. His bio picture alone was enough to command respect from a (relatively) young Iraq veteran, like myself.

There are men and there are real men. My Lima Charlie colleague Rob Swain and I were recently given the honor of sitting in an interview with the legendary Colonel Douglas Dillard. I was even given the opportunity to ask him a few questions. Colonel Dillard is a 35-year combat veteran with overseas service bars lined-up to his elbow and more decorations than any soldier could imagine. His bio picture alone was enough to command respect from a (relatively) young Iraq veteran, like myself.

I joined the Army when I was 17 years old, and remember feeling relieved when I knew I was able to get out of where I was in Massachusetts. To me, the Army was a way out, and the risks of war were low since it was 1994 and my chances of being deployed to a combat zone were not realistic.

After learning that his stepfather was deployed to North Africa in the early years of World War II, Colonel Dillard enlisted at just 16. He insisted that his mother sign the necessary releases to ensure he had the opportunity to become a soldier — a paratrooper. “I pressured my mother to sign the papers so I could go ahead and enlist”. “When we learned about the Paratroops, we all wanted to become Paratroopers” Dillard recalls. After much haranguing, Mrs. Dillard signed the papers allowing her only child Doug to join the United States Army.

When the papers were signed, Mrs. Dillard herself joined the WACS, and with that the entire Dillard family was off to war. Even at a young age, Dillard felt the call to duty, like it was in his blood. He knew exactly what he was doing and what he was signing up for. How many kids do you know would do the same thing today?

On July 3rd, 1942, the would-be Private Dillard left for basic training. This began a military career that would span 35 years, 3 wars, the birth of modern special operations, and military intelligence at the highest levels. But that summer, the war was going poorly and he was just one of hundreds of thousands of young men boarding trains and busses for training sites all over the country.

In November, Dillard and the rest of the newly formed 551st Parachute Infantry Battalion had completed training and were brought before the battalion surgeon who ordered the men to strip. Each man was then checked for parachute tattoos. Whoever was found to have the distinctive tattoos was told to put on their clothes and board trucks waiting to take them to a tattoo parlor in Columbus, GA to have them covered. “I got a stupid tattoo on my left forearm that I wish I never had, but one guy, Montgomery had a huge parachute across his chest and he was a bloody scabby mess for weeks after that”, Colonel Dillard said. “We ribbed him the rest of the time he was in the unit”.

On August 15, 1944, less than a month before his 18th birthday, Douglas Dillard jumped from a C-47 transport into the flack-filled skies of Southern France as part of Operation Dragoon. Within 24 hours of landing the 551st had captured the Major-General in control of the district and the General in charge of the corp and his staff. “We completely eliminated the command and control for that area.” He continued, “When we captured the command post, a bazooka man blew the door off and my buddy rushed in, stuck his Thompson in the General’s belly and told him he was his prisoner”. In the confusion that followed a German staff officer was found who could speak English. He told the Americans the General could not officially surrender to an enlisted man. So radio calls were made and a captain from another company was found to take the surrender. When the captain arrived the General apologized for not being able to properly surrender because one of “these ruffians” took his pistol. The captain demanded the return of the general’s sidearm from the men, but got no reply. Dillard concluded that story by saying “I have that pistol in my safe today”.

As a result of the battalion’s actions, the 7th Army could advance steadily up the Rhone Valley deeper into France, while the 551st fought its way along the coast towards the Italian border, liberating the towns of Cannes and Nice along the way. What followed was 3 months of artillery barrages courtesy of the Austrian 5th Division based on the peaks of the Maritime Alps. But the 551st held its ground due to constant patrolling until relieved in early winter. Dillard and his battalion were sent to Northern France to rest, reequip, and prepare for the upcoming airborne assault across the Rhine. But Hitler had other plans.

On the evening of December 16th, at the reserve area in Rheims, the 551st were preparing for the jump into Germany, when its CO was ordered to report immediately to the Division Headquarters. He returned and told the men to be ready to move out the next morning. The Germans had launched an offensive in the Ardennes. Dillard was headed to Belgium and the Battle of the Bulge.

Chaos reigned as the battalion prepared to move towards their objective, the crossroads town of Bastogne. Orders were issued and rescinded, as the German advance cut roads and occupied towns before reinforcements could arrive. The 551st eventually found itself on the road for two days, constantly changing routes to avoid German checkpoints and soon learned that Bastogne had already been surrounded. The 551st was then re-routed to Werbomont and joined elements of the 82nd Airborne. In the actions that followed, the 551st took heavy casualties but played a key role in the initial counter-attacks that help stop the German onslaught.

At Dairomont, Belgium on January 4th 1945, Sgt. Dillard was 2nd in command of a platoon that led one of the final bayonet charges of the war. With his grease gun frozen and armed with only his sidearm, he and two platoons of men charged two German machine gun positions. “The Germans were lying there with their breath coming out like steam.” The result was 64 Germans KIA, with one U.S. casualty. But on January 7th their luck had changed. The 551st’s commander Colonel Joerg was ordered to take the heavily fortified garrison town of Rochelinval. Joerg protested exclaiming his men were tired and frostbitten due to lack of proper clothing. Those protests were ignored, and the fate of the 551st was sealed.

The first attacks were repelled and losses were staggering. Advancing across open ground the men were exposed to devastating artillery fire. Eventually the town was taken but their leader Col. Joerg was killed in the final attack. “There was only five people left in my company because of the intense fighting”, Colonel Dillard concluded. The 551st had entered the Bulge with over 800 officers and men, and on January 8th, only 14 officers and 96 enlisted men remained. “After the battle General Gavin came to us and said the regiment was to be deactivated in the field”. Sgt. Dillard, who at only 18 years of age had lost so many friends, now saw his remaining buddies scattered to other units in the 82nd. He was transferred to the 508th PIR, where he continued to serve exceptionally until VE day.

Colonel Dillard always spoke very matter-of-factly about his time in combat, even describing D-Day as “just another day” on-the-job. Impressive, considering he also fought with great distinction in Korea and Vietnam … just doing his job. Listening to Colonel Dillard I realized that from 1942 to 1946 he had advanced from a Private to Sergeant Major. One would certainly have to be one hell of a soldier to accomplish that feat! But he didn’t stop there.

Have you ever heard of clandestine operations during the Korean or Vietnam wars? How about in Czechoslovakia? Neither did I. No, this is not the prelude to a spy novel. The good Colonel was the Director of Human Intelligence and Collection Requirements for the Defense Intelligence Agency, and one of the founding fathers of Special Operations. What’s more, he is one of the original members and leaders of the Army Counterterrorism Unit: 1st Special Forces Operational Detachment-Delta, commonly known as, “Delta Force”. Much of Colonel Dillard’s gallant service in Korea remained classified until 1990.

Upon his return from Korea, he continued to serve in military intelligence in Europe, coordinating collection between Military intelligence groups and the CIA, and in 1967 he was sent to Vietnam to head up MACV in the Mekong Delta. MACV and its Phoenix Program were created to disrupt the Vietcong political infrastructure in South Vietnam. When he completed his second year command tour he moved to his next assignment, with the 500th Military Intelligence Group, where he feels he did some of his finest work.

In 1977 Colonel Dillard retired from the military and began a new career in the private sector, and is also a published author of several books about Special and Airborne Operations in the Korean War. Today at 90, he lives in Maryland near his 4 daughters, 7 grandchildren, and 8 great-grandchildren. “I am mothered quite a bit these days” is how he explains it.

[Video by Senior Airman Rusty Frank, 52nd Fighter Wing Public Affairs]

I have spent time at places like Camp McCall, Fort Bragg and Fort Benning. I have been surrounded by regular Army, Special Operations and Intel my entire career. I remember being in the WWII barracks at Fort Jackson and Fort Bragg during training, and the aura of history these places had. They never had tangibility or a face that I could relate to, but now Colonel Dillard is that face to me. Hearing him talk about his career left me speechless; which anyone who knows me is not a trifling statement. He is what films are made of, and why books are written.

I cannot articulate the profound effect his story had on me, because there are no words with which to describe. I can say that I feel lucky to have been able to ask him a couple of questions and listen to my colleague interview him, who was equally in awe, and who had studied the history of Colonel Dillard obsessively before our interview. It was an honor to have even a fraction of the time he spent with Lima Charlie. In the short time I was able to speak with Colonel Dillard, he emulated what a true leader is and what a man should be. He is a soldier’s soldier. A real man.

[This article was originally published June 1, 2016]

Don Johnston and Rob Swain, with Anthony A. LoPresti, Lima Charlie News.

SGT. Johnston served with distinction in the U.S. Army as a non-commissioned officer, with tours in Central America, Africa and the Middle East, from 1994 to 2008. Mr. Johnston was with the U.S. Army Civil Affairs and Psychological Operations Command (USACAPOC), on active duty in Iraq during Operation Iraqi Freedom. He was part of a four man team that was directly assigned to A Co., 2nd BN., 10th Special Forces Group (A).

Lima Charlie provides global news, featuring insight & analysis by military veterans and intelligence professionals Worldwide.

For up-to-date news, please follow us on twitter at @LimaCharlieNews

![A Trump war crime pardon dishonors us all [Lima Charlie News]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/A-Trump-war-crime-pardon-dishonors-us-all-Lima-Charlie-News-480x384.png)

![Image Imagine a Global Space Community ... The Space Foundation Can [Lima Charlie News][Graphic by Anthony A. LoPresti]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/Space-Foundation-Space-Symposium-Lima-Charlie-News-480x384.png)

![Image Memorial Day may soon be a remembrance of democracy and those who had the courage to defend it [Lima Charlie News]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/Memorial-Day-may-soon-be-a-remembrance-of-democracy-and-those-who-had-the-courage-to-defend-it-Lima-Charlie-News-480x384.png)

![The Mind of Bolton - AUMF and the New Iran War [Lima Charlie News]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/Inside-the-mind-of-Bolton-Lima-Charlie-News-main-01-480x384.png)

![A Trump war crime pardon dishonors us all [Lima Charlie News]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/A-Trump-war-crime-pardon-dishonors-us-all-Lima-Charlie-News-150x100.png)