Part 1 of Capt. Gail Harris’ report about the recent Intelligence & National Security Summit and the challenges facing the Intelligence Community.

In the aftermath of 9/11, I was often asked, was it an intelligence failure?

My answer was always the same, ‘Yes, but not in the way you think’.

| By Capt. Gail Harris, Lima Charlie News

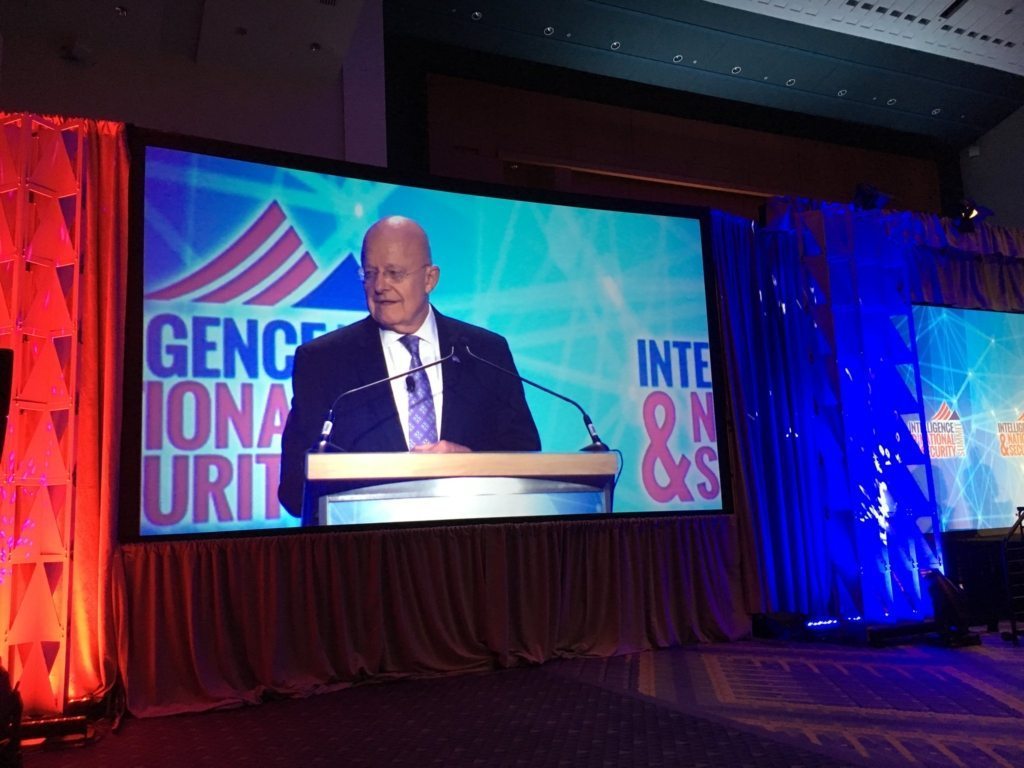

Over the past few years, our nation has held a very public conversation about our work and how we should conduct it as an Intelligence Community. I believe a lot of what has been lost in the public debate about how we conduct intelligence is why we even do it in the first place. Why does any nation state conduct intelligence? … I think we conduct intelligence … to reduce uncertainty for our decision-makers … We can’t eliminate uncertainty … but we can provide insight and analysis to help their understanding and to make uncertainty at least manageable so that our national security decision-makers can make educated decisions with an understanding of the risk involved, so that we, our friends and allies, can operate on a shared understanding of the facts of the situation.

– Remarks as delivered by The Honorable James R. Clapper Director of National Intelligence

Wednesday, Sept 7, 2016

Last week I attended the third annual Intelligence and National Security Summit in Washington, DC. The conference is co-hosted by AFCEA International and the Intelligence and National Security Alliance (INSA)(#Intelligence2016).

The purpose of the summit is to provide a public forum to discuss the successes, set backs and challenges of the US intelligence community. This is always an important topic, but even more so in light of the upcoming change of leadership after the upcoming Presidential election. No matter who wins, she or he will most certainly bring in a new national security team.

Going into the conference I was most interested in three topics:

First: Which national security threats did intelligence community leaders consider the most serious and what were the biggest challenges in addressing them?

Second: For the last few years, in their annual threat assessment report to Congress, the intelligence community has identified Cyber as our number one security threat. What are some of the continuing challenges and what is being done to address them?

Third: What is being done to address the problem of information sharing in an era of “Big Data”?

I’ll start with the information sharing/big data issue. In the aftermath of 9/11, I was often asked, was it an intelligence failure? My answer was always the same, “Yes, but not in the way you think”. The conventional wisdom is that prior to 9/11 the intelligence community was stove piped and was not sharing information. There was actually a great deal of sharing going on. The amount of data being sent and received between the various intelligence organizations was enormous. What wasn’t always being shared was the analysis of that data.

Now to be clear, the various intelligence agencies and commands did produce large numbers of analytical reports to include breaking news types of reports, and products with more in depth analysis; but what wasn’t being done on a consistent basis was picking up the phone and doing informal consultations with other members of the intelligence community as you conducted the analysis to get their take on various national security issues.

There also was not a consistent alerting procedure in place. By that I mean simply calling analyst(s) in other organizations to make sure they had seen raw data and/or an analytical report that you considered important, to see if they agreed or had a different take and/or more information on a situation. I can’t emphasize enough the importance of the last part of the above quote from James Clapper of operating “on a shared understanding of the facts of the situation”.

Why is this important? The intelligence community deals with such a large amount of data, you can’t always assume people who have the “need to know,” and who should have access to the data, have seen all of the available information on any topic. The challenge of the intelligence professional is to rapidly sort through all of the data in order to develop usable intelligence analysis, enabling decision makers and warfighters to make informed decisions. Depending on the scenario, these decisions sometimes have to be made within minutes. Sometimes seconds.

I talked about this some in my last article (CENTCOM and the ISIS Threat – Was there a Politicization of Intelligence?), but a 2007 figure indicated that every 24 hours the intelligence community collected one billion pieces of data. In that same year speaking at an unclassified conference in Chicago, Dr. Michael Wertheimer, the then Assistant Deputy Director of National Intelligence for Analytic Transformation & Chief Technology remarked:

“Of the data we’re collecting, that is genuinely intel, not fluff – it’s already been filtered and selected – we’re only analyzing about one ten-millionth of the data we’re collected today; one ten-millionth. Now, that number could be completely wrong. I think I got the number of zeros right, and if I’m not right it was either right a year ago or it will be right in the next year. That’s how fast it’s growing.”

I’m sure these numbers have gotten much higher. The takeaway should give some insight into the outstanding job the men and woman of the intelligence community are doing to identify threats, and keep us safe in spite of these challenges. Much of this information is raw data. It is up to the intelligence analyst to piece it together to determine if anything significant is going on. Think of someone shoving you into a room filled with thousands of puzzle pieces, and then telling you to put it together in a few hours.

Think of someone shoving you into a room filled with thousands of puzzle pieces, and then telling you to put it together in a few hours.

The approach the intelligence community has taken to solve this problem, is to develop computer hardware and software to help sort through the data, display it in a usable format for analysts, then get the analysis quickly into the hands of the decision makers and warfighters in whatever form works best for them. When I first started working intelligence in the 1970’s, we’d get a report on a military unit and then have to manually annotate its position on a chart. If it was a geopolitical report, you had to either print a copy and stick it in a file cabinet, or commit it to memory along with thousands of other similar reports.

Starting in the late 1970’s, the intelligence community developed hardware and software that would receive the reports, automatically pull out location data, and display it on a computer screen. You could write a history of how the intelligence community has developed by simply focusing on these types of advances. For example, while I was on active duty they never came up with a good computer solution on how to display geopolitical reporting, other than setting up storage files. I always found the best answer for that was to simply call up analysts at other intelligence organizations who were subject mater experts.

The standing joke was the real experts on various intelligence subjects were little old ladies wearing tennis shoes and working in the basements of major intelligence organizations. As a lot of intelligence history has been declassified, you’ll find that indeed there were a lot of women working in intelligence who did great things and received very little credit or notice in the public. But that’s another blog.

At last week’s summit, Ms Betty Sapp, the Director of the National Reconnaissance Office (NRO), the agency in charge of developing our intelligence collection satellites, remarked that when developing new systems they are now much more focused on the ground processing capabilities. They want to ensure the systems used to process data can learn and operate at the speed of cyber, and not at the speed of humans. Ms Sapp also stated that processing the large amount of ground data is tough. In the past, the NRO was ahead of the private sector and developed its own processing capabilities. That has changed, the private sector is ahead, and the NRO is now buying commercially available services.

Other senior members of the Intelligence Community also commented on this issue. Lt General Vincent Stewart, USMC and Director of the Defense Intelligence Agency said the challenge going forward was how to deliver content at the speed of the network in a way that helps decision makers. Delivering content a day late isn’t going to work.

Admiral Michael Rogers, USN, Commander U.S. Cyber Command, and the Director of NSA also said the challenge was how to continue to create meaningful intelligence. Technology changes at an incredible pace, and analysts have to operate within that environment. Rhetorically, he asked how are we positioned to stay ahead of the problem sets. Rogers said the answer was people, integration, and innovation. He also said artificial intelligence and machine learning helps you get to scale with the volume of activity you have to analyze. If you can’t do that, then you’re behind the power curve.

John Brennan, the CIA Director said information must be processed using agility, integration, and in lightening speed. This includes the need for new approaches and thinking. Robert Cardillo, the Director of the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency reminded us that intelligence agencies shine when they work with each other. Cardillo also said we are long past human centered analysis of the data, and the focus is on how we use and automate the data. We can now expose data in ways that we’ve never used before.

What does all of this mean, and is it really significant?

To put this in some context, I’ll use an example from my career. In the late 1970’s I was working as an intelligence watch officer in support of the Navy’s 7th Fleet. The job entailed tracking all, and I mean all, of the military forces of potential adversaries by monitoring thousands of intelligence reports sent out by intelligence agencies, collecting information from all types of systems, satellites, aircraft, underwater listening devices, etc. The focus was not just on where they were located, but what they were doing, and what were their intentions. Was this just a training exercise, or were they planning on sending forces on an operational deployment of some sort? Was the pretense of training being used to cover an upcoming major operation? You had to take all of this information, fuse it into actionable intelligence information, and send it to warfighters and decision makers via reports; and, if it was really time sensitive, contact them via secure phone and teletypes.

For instance, if the Soviet Union was flying aircraft over international waters, you had to send out reports and update them every 10 minutes. The Soviets tried to conduct operations as covertly as possible, so even if you had no updated information on the aircraft location, you had to – as Captain Kirk once said to Spock – “guess”.

7th Fleet positioned their military forces based on what the intelligence analysts told them. If the Soviets were launching aircraft to conduct a simulated missile strike against a US Carrier Strike Group (happened pretty often during the Cold War), the Navy wanted to be able to have enough time to react.

Once more, we play our dangerous game, a game of chess against our old adversary – The American Navy. For forty years, your fathers before you and your older brothers played this game and played it well. But today the game is different. We have the advantage.

– Captain Ramius, The Hunt for Red October

One day a Soviet ballistic missile submarine, we intelligence types code named Delta, communicated while on patrol. Submarines on patrol rarely communicate, that’s why they’re called the Silent Service. A short while later it surfaced. This was unprecedented.

The particular class of submarine that surfaced carried nuclear tipped missiles with a 4200 nautical mile range. I was the intelligence officer on duty that day, and had to make a decision on whether it was preparing to launch its missiles, or there was something else going on. If the submarine was preparing to launch, I had to give 7th Fleet enough notice so they could attempt to destroy the submarine before that could happen.

I did extensive coordination with NSA, the Pacific Fleet intelligence staff in Hawaii, and the Defense Intelligence Agency. I knew that the Delta did not have to surface in order to launch its missiles. I also knew they were aware we knew that, so were they trying to keep us off guard? NSA was sending out lots of reporting that allowed me to determine the Soviets were not in an increased defense status, nor did they appear to have other military forces on increased alert. Since most of the NSA reports were basically raw data, I also called them up to discuss the situation, to make sure I was coming to the right conclusions. I also had reps from NSA working with me as part of an integrated team who were of tremendous help in analyzing the raw data coming in. Informal coordination with other intelligence agencies confirmed there was nothing going on politically between the US and Soviet Union to cause them to launch nuclear missiles at us.

I finally concluded, based on the nature and composition of Soviet surface and air assets that I could see through reports heading toward the submarine that it had suffered either a mechanical problem or medical emergency. I was right…that time.

As I recall, I was able to do all of this analysis and coordination in about 15 or 20 minutes. I could not have done the analysis without the timely intelligence reports and informal coordination from NSA and others. Because we were able to get the critical intelligence and analysis out quickly to our warfighters, a major crisis was averted. Intelligence analysts who specialized in support to warfighters make critical analysis and decisions like this all of the time. Why the emphasis on informal coordination? We were a military organization and if we had used a formal chain to coordinate our analysis we would have had to go through our bosses. That could have taken a few days.

I’ve always felt that the continuing challenge of the intelligence community was developing the best analytical practices, and hardware and software solutions, to sort through the vast amount of data to get actionable intelligence to the right people, in the format, and timeliness needed. This is the only way decision makers and warfighters can make informed decisions. It is an enormous and constantly evolving problem. As technology enables the development of intelligence community collection systems that collect more data than their predecessors, there is also the requirement to develop new systems to process the data.

In spite of technological advances, people still remain a very important part of the equation. The heads of the NRO and NGA were asked during their session if there was a shortage of people. The response: there is a gap between the people they have and what they need. They’re addressing that by setting up rapid analytical teams against some problem sets.

According to Ms Sapp, the NRO is working on a machine that can learn how to work with multiple types of intelligence, and learn based on inputs from analysts. Mr. Brennan advised we don’t always need more people, sometimes we just need to be more efficient. General Stewart expressed the need to have more Russian analysts.

There was a time when Russia was the only game in town. After 9/11, the major focus shifted to counter terrorism analysis. This was mentioned several times during the summit. Having spent much of my career focused on Russia, to then readjust and focus on the Middle East during and after the first Gulf War, I’ve witnessed major intelligence shifts. But now, in light of the threat of Russian cyber warfare, Russia’s ambitions in Ukraine, and the kick off this week of Russia-China joint naval exercises, our intelligence community is going to have to retrain its assets to focus more on Russia and China.

This raised another issue. I began to wonder if I had better lose some weight in case I and other old Cold War hands are recalled to active duty. I wouldn’t mind being recalled, but I wouldn’t be able to fit back into my uniform!

Think I’ll end here. My next article (Part 2) will address some of the Cyber issues raised at the summit. As always, my views are my own.

Gail Harris, Lima Charlie News

Captain Gail Harris (U.S. Navy, Ret.), was the highest-ranking African American female officer in the US Navy at the time of her retirement in 2001. Her 28 year career in intelligence included hands-on leadership during every major conflict from the Cold War, to El Salvador, to Desert Storm, to Kosovo, and she was at the forefront of one of the Department of Defense’s newest challenges, Cyber Warfare. Gail also writes for the Foreign Policy Association, is author of “A Woman’s War”, serves as Senior Fellow for the George Washington Center For Cyber & Homeland Security and is a Senior Advisor for the Truman National Security Project.

Lima Charlie World provides global news, featuring insight & analysis by military veterans, intelligence professionals and foreign policy experts Worldwide.

For up-to-date news, please follow us on twitter at @LimaCharlieNews

![Israel-Hamas Cyberwar, when old warfare meets new [Lima Charlie News]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/Israel-Hamas-cyber-warfare-01-e1558501438770-480x384.jpg)

![Image GailForce to Space Force: 'Make it so' - the Space Force debate continues [Lima Charlie News]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/Space-Force-01-480x384.png)

![Image Huawei – China’s telecom giant hits a giant wall [Lima Charlie News]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/Huawei-–-China’s-telecom-giant-hits-a-giant-wall-480x384.png)

![Image U.S. 'Space Force' looking more and more like space reality [Lima Charlie News]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/Space-Force-looking-more-and-more-like-space-reality-480x384.png)

![Image GailForce: Blinking Red - Cyber War and Malign Influence Operations Today [Lima Charlie News][Graphic: Lima Charlie News]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/GailForce-Blinking-Red-Cyber-War-and-Malign-Influence-Operations-Today-Lima-Charlie-News-01-480x384.png)

![Israel-Hamas Cyberwar, when old warfare meets new [Lima Charlie News]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/Israel-Hamas-cyber-warfare-01-e1558501438770-150x100.jpg)