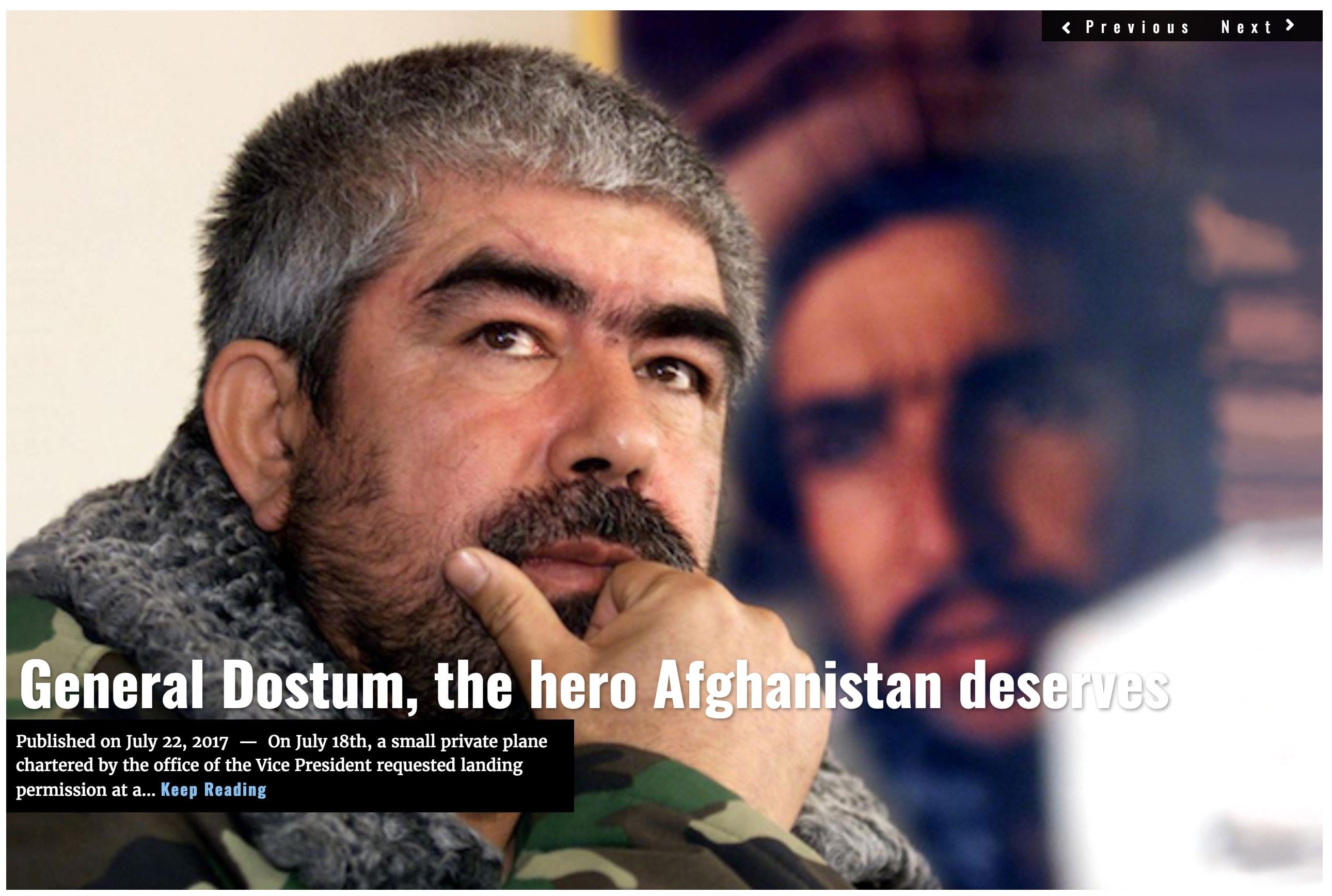

Opinion: After nearly two decades at war, the U.S. effort to build the Afghan state has been for the most part, a failure. In order to turn its sails towards victory, America needs to reassert its influence on Afghanistan’s economy, governance and security.

One year after the Trump Administration’s formal reassessment and strategy shift on the war in Afghanistan, it seems that our regional adversaries are getting closer to a checkmate. The question we are asking now is, “how do we not lose?” Winning, it seems, is no longer an option … Or is it?

After seventeen years and $132 billion in direct U.S. assistance, the “crawl, walk and run” strategy for Afghanistan has come to a impasse somewhere between crawl and walk. There is no denying that Afghanistan has made substantial advances in its social, economic and political sectors since the 2001 U.S. toppling of the Taliban regime. Yet, thirty-nine years after Soviet tanks rolled through downtown Kabul, the country is still at war with no clear end in sight.

Despite being overthrown in 2001, the Taliban has yet to be offically labelled a Foreign Terrorist Organization by the U.S. Instead, the Taliban are considered a Specially Designated Global Terrorist group, thus confusing everyone.

“The Taliban, per se, is not our enemy,” said former U.S. Vice President, Joe Biden, a decade into the war in Afghanistan. The indecisive position of U.S. policy is rooted in potential political reconciliation. Since the U.S. government does not negotiate with terrorists, the U.S. could not assist the Afghan government in negotiating peace with the Taliban if they were labeled a terrorist organization.

Labels aside, U.S./NATO troops, Afghan security forces, and civilians are targeted by the Taliban on a daily basis. Who is the enemy and more importantly, why are we in Afghanistan?

![Image [TORKHAM, March 7, 2017 -- Vehicles en rout to Afghanistan line up near Pak-Afghan border in northwest Pakistan's Torkham on March 7, 2017. (Xinhua/Sidique)]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/1.jpg)

U.S. strategy and policy in Afghanistan has been dysfunctional on so many levels that last year’s reassessment triggered a sigh of relief by both the Afghan government and U.S./NATO command on the ground. The U.S. has been outmaneuvered politically, militarily and economically by the “Fantastic Four” – Pakistan, Iran, Russia, and China. Not only does the U.S. need to rethink its strategy, it needs to rethink whether asserting leadership in the region is a priority. This does not seem to be the case for many at the White House.

Critical to any analysis, the U.S. needs to focus on the three pillars of economics, governance and security. While the current US/NATO advisory mission assists the Afghan government in these areas, its focus is highly skewed towards security assistance. Without heavily assisting the Afghan government towards good governance and building its core economy, this 17 year effort will be useless.

The Economy

The Afghan economy is completely reliant on foreign aid and a military presence. A sustainable economy with foreign direct investments is essential for the creation of long-term employment opportunities and a stable middle-class. When the Soviet Union invaded Afghanistan in 1979, its GDP was $3.7 billion (adjusted for inflation). This is approximately 33% greater than its GDP in 2001 when U.S. Special Forces parachuted into Tora Bora. Afghanistan was in a prolonged state of economic decline for 22 years, and then, with the toppling of the Taliban regime, it was infused with billions of U.S. dollars a year in foreign aid.

Today Afghanistan’s GDP is hovering at approximately $20 billion, a significant increase. Yet, the country has transformed into a military economy funded by foreign aid. Without the $5+ billion in annual contributions from the U.S. and its NATO partners, Afghanistan, a nation that last year collected approximately $2 billion in total revenues, would be unable to support its $7 billion national budget.

What about foreign investment?

From dealing with local strongmen to fending off bribes from government officials, investing in Afghanistan is nearly impossible. When facilitating private investments on behalf of the Pentagon, the biggest hurdle I came across was not convincing investors, but rather, convincing Afghan government officials to engage. On paper, Afghanistan is an ideal place to invest, but strictly on paper. Not only are most laws unenforced, they’re unknown to those in charge of enforcing them.

The Afghan government does currently promote investment. Yet this promotion is mostly rhetoric. In practice, the heavy burden of research into available investments has been placed mostly upon potential investors. Neighboring countries, meanwhile, provide much greater deal facilitation. Afghanistan needs its own foreign investment direct investment office to formulate comprehensive medium-large scale opportunities for investors. This office should do most, if not all of all the research and legwork, then simply present these opportunities to internationals while leveraging off the nearly 40 embassies located in Kabul. A professional investment office should be able to hand a draft business plan to investors, one that, in the least, outlines the details of investment return, capital costs, operations, government assurances, and multilateral guarantees.

The Contractprenuer

The U.S. distributes billions of dollars per year via government contracts in Afghanistan, thus spawning a new type of entrepreneur: contractpreneuers. Contractprenuers are not real entrepreneurs, rather, just implementing partners on short to medium term assignments with very lucrative financial incentives. When the contract is up, so is the business and its employees.

Afghanistan’s economy needs to be revamped by investment in industries with long-term sustainability and strong multiplier effects for the economy through trickle-down employment opportunities. The U.S. Department of Defense used to have a specialized investment team that facilitated large-scale FDI’s in Iraq and Afghanistan, the Task Force for Business and Stability Operations (TFBSO). A new, but more focused, version of TFBSO needs to be created with a strong working relationship with senior officials from the Presidential Palace’s investment office. One of the biggest hurdles for investors in Afghanistan is not insecurity, but rather, the Afghan government itself.

Legislation and fiscal reforms need to be enacted in Afghanistan to allow for an investment-friendly environment – not just on paper, but in practice. TFBSO worked with NASA and the US Geological Services in determining that Afghanistan has over a $1 trillion in mineral wealth. Some argue that the number is actually closer to $3 trillion. Before mineral wealth can be attained, the supporting industries need to be established first, i.e., energy generation, railways, dry-ports, cement and steel manufacturing, etc. Afghanistan needs its industrial revolution. With a businessman at the helm of the U.S. government, this can be accomplished as a win-win for both the U.S./international investors and the Afghan people.

Regional countries are very interested in Afghanistan’s economy, yet the U.S. is not. This disinterest is baffling. For many years, the U.S. Department of Commerce only had two in-country employees, before it fired the last remaining representative on the eve (literally the eve) of a significant investment conference it assisted in hosting in Dubai. China continues investing in Afghanistan for its One Road, One Belt initiative through Central Asia, including hoarding mining rights without making any real stakes. China is now extending its China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) investment initiative to Afghanistan.

Will the U.S. continue to sit on the economic sidelines as foreign rivals capitalize on her security efforts, or will it work with Afghanistan to create win-win investment opportunities?

![Image A money changer holds a stack of U.S. dollars at Kabul's largest money market April 23, 2014. (Reuters)]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/4.jpg)

Corruption

Corruption, not the insurgency, is the real existential threat to Afghanistan. Given the tremendous influx of capital into Afghanistan since 2001, corruption should be expected but never tolerated. Anti-corruption rhetoric in Afghanistan has become precisely that: rhetoric.

General John Allen, former Commander of the U.S./NATO forces in Afghanistan was once quoted as calling the Taliban a nuisance compared to the corruption. A national survey estimated that in 2015, nearly $3 billion was paid in bribes. To put that in perspective, that is 50% greater than the entire national revenue. It is appalling that the former Senior Advisor on Good Governance (Ahmad Zia Massoud, former Vice President under the Karzai administration) to President Ghani got caught landing in Dubai with $52 million in cash.

The Afghan government needs to get serious about systematically eradicating the culture of corruption in Afghanistan from the executive level down.

Though the government’s recent establishment of the Anti-Corruption Justice Center (ACJC) is promising, it’s not enough. The U.S. also has to make it a priority over all other considerations and put in place a zero-tolerance policy towards corruption.

The Afghan government must give its fullest support to an undercover unit that apprehends corrupt officials, from low-level police officers to high ranking ministers. It then needs to immediately prosecute violators through a special court (such as the ACJC) and enforce jail time without the intervention of Wasita (personal connections). Additionally, a unit needs to be created that strictly focuses on bringing to justice former accused government officials. Past offenders should not be beyond the arm of the law.

Also effective, extradition treaties should be a baseline requirement of every country that donates to Afghanistan – no extradition, no donations. The U.S. still does not have an extradition treaty with Afghanistan, even though most dollars stolen in Afghanistan are U.S. taxpayers’ hard-earned income. A message has to be sent that if you engage in corruption with U.S. granted money, you may land in a U.S. penitentiary.

Without a strong economy and increased job opportunities, disenfranchised Afghans will continue turning towards alternative methods of income generation – if not abandoning the country and fleeing in hoards. Hundreds of thousands of Afghans have already left for, among other places, Europe with many more preparing their exodus. Working for foreign-funded insurgencies and cultivating illicit crops (Afghanistan produces 90 percent of the world’s opium supply) are two income generators that immediately come to mind, both of which are global security threats.

![Image Road construction near an iron ore mine near Bamiyan, Afghanistan, in 2012. The country’s lack of infrastructure has hindered efforts to exploit its natural resources. Credit: Mauricio Lima]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/2.jpg)

Governance and Security

Governance and security are different sides of the same coin in Afghanistan. Weak governance has led to greater insecurity, and insecurity has led to a loss of confidence in governance.

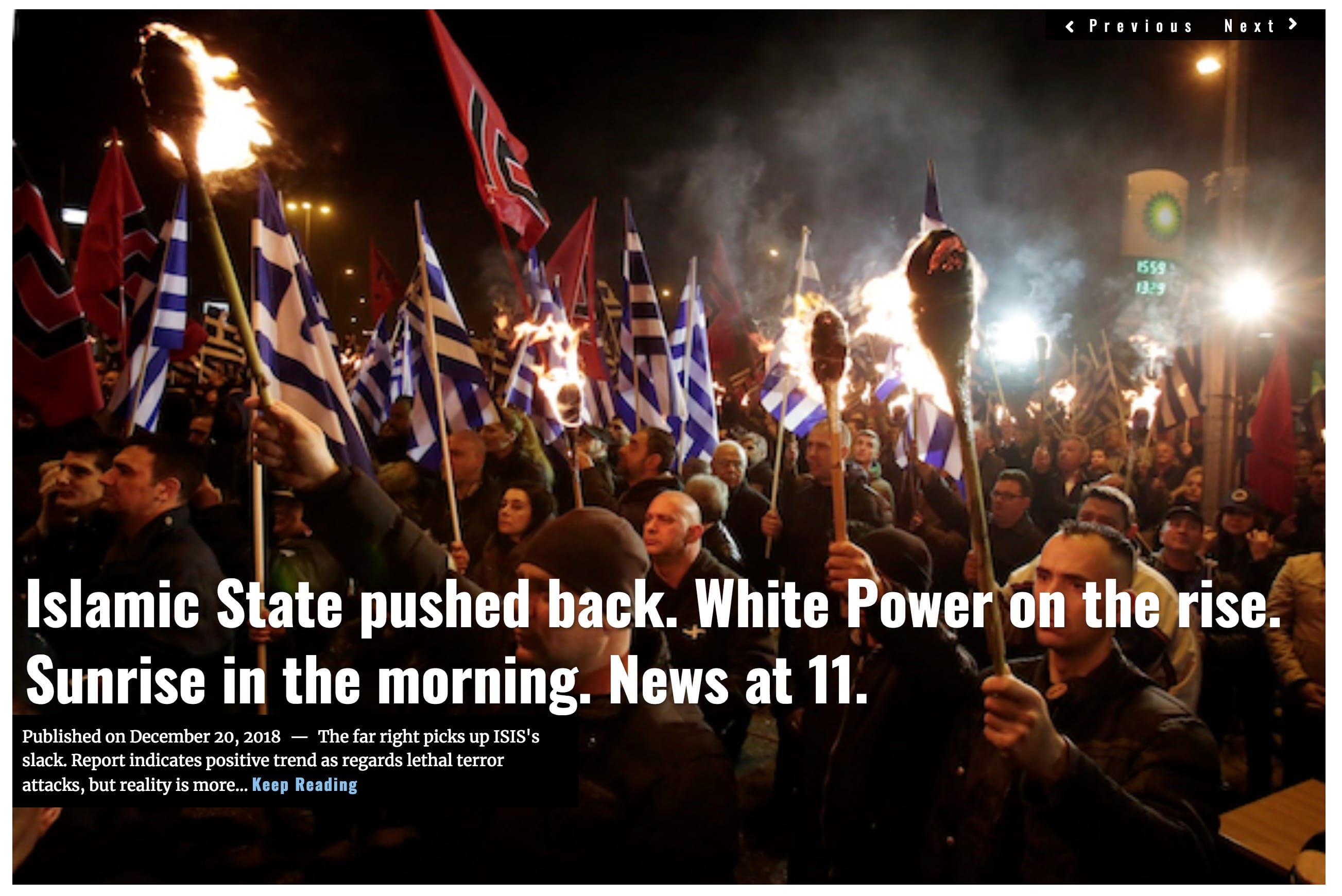

Over the past few years, the aforementioned “Fantastic Four” have tried to undermine the political leadership of the United States and the Afghan government. A term has been coined for this new reality: multipolarism.

By hosting meetings and reconciliation discussions, and by maintaining direct communication with terrorist and insurgent groups, these four countries are jockeying for their own self-interests at the expense of Afghanistan. Most recently, Russia hosted a peace summit giving the Taliban a global voice, and for the most part, the Afghan government was utterly unprepared for the meeting. These reconciliation meetings need to be led by the United States, not hostile governments who have covertly undermined the Afghan people for decades. The U.S. needs to reaffirm is political leadership.

Pakistan is a complicated case and any efforts to simplify it are bound have unpredictable consequences. On the one hand, Pakistan’s support for destabilizing actors in Afghanistan is hardly debatable. Yet it still holds the key to Afghanistan’s stability and therefore should be treated with exceptional care. Could Pakistan be convinced to forgo treating Afghanistan as an extension of its “strategic depth” and instead treat Afghanistan as a sovereign state, an equal, and a trading partner? Could Pakistan be assured that India’s presence in Afghanistan is an economic necessity, not a political and security threat as the Pakistanis perceive it? Should he engage, President Trump faces a historic challenge with the odds stacked staggeringly against him. If proven successful, however, “deal maker” Trump would be the first.

“We ought to think about Afghanistan as a modern-day frontier between civilization and barbarism.” – (ret.) Lt. Gen. and former National Security Adviser HR McMaster, October 23, 2018

Beyond the macro level geo-political regional conflicts there are additional problems within the advisory mission in Afghanistan. The current U.S./NATO advisory and diplomatic mission has a major elephant in the room – force protection or better known as, security protocols. U.S. and International advisors are bound to the walls of their concrete fortresses and only allowed to truly engage with their Afghan counterparts for a few hours a week if they’re fortunate.

Some advisors can go months without leaving the base, conducting advisory sessions through “telephonic sessions” – which is mostly useless in my humble experience. When advisors do leave the compound they are accompanied by multi-vehicle convoys (usually armored Land Cruisers or MRAPS), armed military “guardian angels” (sometimes inside the same room), with a rifle strapped around their chest. A great way to build trust.

The force protection measures are set in place to decrease the risk of losing life, but they directly undermine the entire purpose of advisors. My team’s advisory mission was targeted primarily at the Ministry of Finance, a non-security ministry, with mostly young, foreign-educated staff members. Suited and booted, we’d have to constantly re-adjust our pants while walking through the marble floored hallways since we all had pistols strapped to our belts. In order to “build-trust” we would break down our M4 rifles and put them in backpacks. Afghans are not stupid, they all knew we wearing bullet proof vests underneath our dress shirts and more heavily armed than Rambo. We wanted them to trust us with extremely sensitive information, while we didn’t trust them over an afternoon tea.

You cannot advise and build capacity in a frontier (pre-emerging) market environment while bogged down inside your headquarters 90 percent of the time. There needs to be a review of the force protection rules to allow for the advisory mission to actually advise while still having basic protective measures in place. Keep in mind, these are the security protocols in Kabul, the capital of Afghanistan. Now imagine how much less trust and interaction there is as you move into the provincial areas of the country – it’s almost non existent. This is a war zone, and a certain amount of risk has to be accepted.

Let’s Be Honest With Ourselves

The recent reconciliation between the Afghan government and the Afghan-led, but Pakistani based Hizb-e-Islami, a radical extremist organization led by Gulbudeen Hekmatyar came out of desperation. The government signed a highly controversial peace accord because the government has been unable to secure Kabul, let alone the country. Though the U.S. supported the reconciliation, the issue is still highly contentious within Afghanistan, especially to the thousands of families that lost loved ones when the “Butcher of Kabul” indiscriminately bombarded Kabul during the Civil War of 1992. This peace deal was a reminder to all how ineffective U.S. strategy has been in Afghanistan, where a proxy of Pakistan and Iran is welcomed by the government to avoid a complete loss of the country to the Taliban.

America needs to call its mission in Afghanistan for what it really is – state capacity building. An admittedly less inspiring phrase than the lofty ideals found in “state-building” but significantly more honest.

Where the U.S. and its allies initially fought against the insurgency, it’s now being fought mostly through a proxy, the Afghan government. The U.S.’s state capacity building mission has been to build Afghan capacity towards managing and defending themselves, and conveniently enough, towards defeating a common enemy – the overall insurgency and extremism in the region.

U.S./NATO dollars work to build almost every aspect of Afghan life including, but not limited to, governance, military, police, health, media, infrastructure, education, agriculture, cultural preservation, gender equality, civil societies, etc. After re-building the Afghan state for the past seventeen years there is little to show for it. The insurgency is getting stronger, political instability is increasing, drug cultivation is at an all-time high and civilian deaths are at the highest rate since the war began.

To salvage the vast time, money and energy expended over the last seventeen years, a critical measure must be implemented: co-administration. The U.S. and NATO needs to have a partial co-administration of the Afghan government. For vital government offices (defense, police, education, urban development, and health) there needs to be a co-administrator who is a representative of U.S./NATO. The co-administrator would be responsible for the capacity development of the crucial ministries, fiscal administration, counter corruption and professional development. Working shoulder-to-shoulder (a famous US Defense Department mantra in Afghanistan) the international co-admins and Afghan officials should work together in building up institutional capacity, rather than the current “here’s the money, report back to us weekly” strategy.

While Afghans will certainly decry the idea due to its perceived encroachment on their sovereignty, given the current rate at which the government is deteriorating, there is no other choice. The “National Unity Government” has proven to be incapable of governing itself. The only thing that is holding back an ethnic civil war is the presence of foreign powers and their fiscal contributions. Embedding co-administrators is the only option left for helping Afghanistan transition from a failed state to an efficient administration.

Conclusion

Operation Enduring Freedom (Oct. 7th, 2001 – Dec. 28th, 2014) and now Operation Freedom Sentinel (Jan. 1st, 2015 – ongoing) have marked America’s longest war. The Afghan people have sacrificed tremendously in refuting extremism. They have believed in America’s promises that Afghanistan can be a peaceful and stable country. But if the migration of hundreds of thousands out of Afghanistan is any indication, it shows Afghans have stopped believing in empty promises.

It’s only a matter of time before the political and economic winds in Washington change, and the ongoing intervention in Afghanistan gets written off. The longest war can’t actually be perpetual. Yet even a measured drawdown can have severe consequences, as it did in Iraq. If Washington leaves, vital private donations from across the globe will follow. The only alternative to success is a narco-state that is used as a terrorist launching pad against the West.

Rather than abandonment, America needs to pursue a holistic approach that encompasses economic, governance, and overall security matters. Without security, there’s no governance, and without governance, there’s no investment.

America must reaffirm its commitment to Afghanistan and its fight against global terrorism.

Waheed Majrooh, Lima Charlie News

Mr. Waheed Majrooh is a former Senior Advisor within U.S. Department of Defense (Pentagon) where he led numerous substantial reform and investment programs in Afghanistan and is currently a Senior Advisor at FRONTIERistan, a frontier market advisory firm (www.frontieristan.com) that focuses on Afghanistan and Iraq. Majrooh is an Afghan-American subject matter expert with over seven years of on-the-ground experience. He currently resides between San Francisco and Washington, DC, while traveling to Afghanistan frequently. He can be contacted directly at wmajrooh@frontieristan.com.

Lima Charlie provides global news, featuring insight & analysis by military veterans and intelligence professionals Worldwide.

For up-to-date news, please follow us on twitter at @LimaCharlieNews

In case you missed it:

![Image Afghanistan – A Bold Solution [Lima Charlie News]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/Afghanistan-A-Bold-Solution-Lima-Charlie-News.png)

![Image Strike a deal with which devil? The many faces of the Taliban [Lima Charlie News][Image: Anthony A. LoPresti]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/Many-faces-of-the-Taliban-Lima-Charlie-News-Anthony-LoPresti-480x384.png)

![Image The fate of Afghanistan’s NATO Generation [Lima Charlie World][Photo: Shamsia Hassani]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/The-fate-of-Afghanistan’s-NATO-Generation-Lima-Charlie-World-Shamsia-Hassani-480x384.png)

![Image Giving the Afghan Air Force Blackhawks is a terrible idea [Lima Charlie News]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/Afghanistan-Black-Hawk-Helocopters--480x384.jpg)

![Image Strike a deal with which devil? The many faces of the Taliban [Lima Charlie News][Image: Anthony A. LoPresti]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/Many-faces-of-the-Taliban-Lima-Charlie-News-Anthony-LoPresti-150x100.png)

![Image The fate of Afghanistan’s NATO Generation [Lima Charlie World][Photo: Shamsia Hassani]](https://limacharlienews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/The-fate-of-Afghanistan’s-NATO-Generation-Lima-Charlie-World-Shamsia-Hassani-150x100.png)